- Release Year: 2009

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: SYBEX-Verlag GmbH

- Genre: Number puzzle, Puzzle, Sudoku, Word

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Word construction

Description

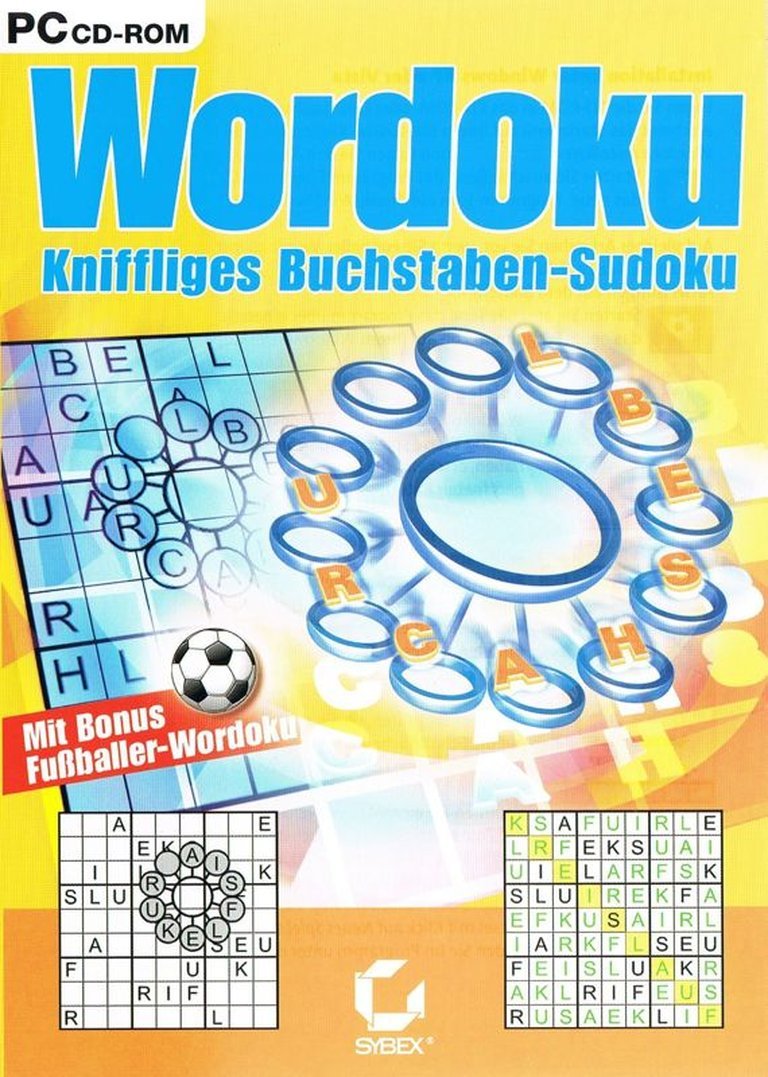

Wordoku is a 2009 commercial puzzle game for Windows that reimagines the classic Sudoku format by replacing numbers with letters. Players must fill a 9×9 grid so that each letter appears only once per row, column, and 3×3 mini-square, with the added twist that the diagonal from corner to corner spells out a nine-letter word that serves as a crucial solving clue.

Wordoku Guides & Walkthroughs

Wordoku Reviews & Reception

pocketgamer.com : Sudoku fanatics will find exactly what they’re looking for in Wordoku, with the added challenge of exercising a few neurons to the left of the brain’s number recognition centre.

Wordoku: Review

In the pantheon of puzzle games, few concepts have achieved the enduring cultural resonance of Sudoku. When Wordoku arrived in 2009, it promised to graft the cerebral rigor of number placement onto the linguistic playground of letters, creating a hybrid that would challenge both hemispheres of the brain. Published by SYBEX-Verlag GmbH, this commercial PC title sought to reimagine a global phenomenon for word lovers—yet its legacy remains as enigmatic as the diagonal words it conceals.

Development History & Context

Wordoku emerged during a fertile period for casual puzzle gaming, when Sudoku fever had swept across newspapers, handheld devices, and early mobile phones. SYBEX-Verlag GmbH, a German publisher better known for educational software, saw an opportunity to localize the Sudoku craze for German-speaking audiences while adding a linguistic twist. The game was distributed on CD-ROM, a format already waning in favor of digital downloads, suggesting SYBEX aimed at a demographic still comfortable with physical media—likely older puzzle enthusiasts and students.

Technologically, Wordoku was modest. Built for Windows in an era when Flash and early HTML5 were beginning to democratize browser-based gaming, it relied on straightforward top-down visuals and fixed-screen layouts. The inclusion of a puzzle generator and print function hints at an educational or offline-friendly design philosophy, catering to classrooms or homes without reliable internet. Yet, the game’s release in 2009 also meant it faced stiff competition from touchscreen PDAs, dedicated Sudoku devices, and the nascent smartphone app market—platforms that would soon render CD-ROM puzzle games obsolete.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Wordoku does not present a narrative in the traditional sense. There are no characters, no story arcs, no dialogue trees. Instead, its “narrative” is abstract and procedural: the silent drama of deduction, the satisfaction of a completed grid, the revelation of a hidden nine-letter word spelled diagonally from corner to corner. This absence of explicit storytelling is not a flaw but a deliberate design choice, aligning the game with the minimalist ethos of classic logic puzzles.

Thematically, Wordoku operates on the intersection of language and logic. By replacing numbers with letters, it transforms Sudoku from a pure exercise in numerical reasoning into a hybrid that demands both pattern recognition and vocabulary awareness. The diagonal word serves as a thematic anchor—a secret message that, once uncovered, provides both a clue and a reward. This mechanic subtly encourages players to think beyond the grid, to consider the interplay between form and meaning.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Wordoku adheres faithfully to Sudoku’s foundational rules: a 9×9 grid divided into nine 3×3 mini-squares, each row, column, and mini-square must contain each letter exactly once. The twist is that instead of numbers 1-9, players place nine unique letters, and the main diagonal reveals a hidden word.

The gameplay loop is elegant in its simplicity. Players begin with a partially filled grid, using logic to deduce the placement of letters. The diagonal word acts as both a constraint and a clue—once identified, it locks in three letters across three mini-squares, providing a foothold for further deductions. The remaining letters are randomized, increasing the cognitive load as players must track which letters are still available in each row, column, and mini-square.

Wordoku introduces several quality-of-life systems to aid players. A “possible” marker allows tentative letter placement without commitment, while an “impossible” highlighter helps eliminate options. These tools are essential given the added complexity of letters over numbers—where numerical sequences are easily memorized, randomized letters demand more active tracking.

The game offers three difficulty levels—Easy, Medium, and Hard—adjustable via the number of pre-filled “givens.” Higher difficulties reduce starting clues, forcing deeper logical leaps. A timer and scoring system add pressure, with bonus points awarded for swift completion. The inclusion of a solver and note-taking features further supports both novices and experts.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Wordoku’s world is abstract, defined by grids, letters, and the quiet hum of concentration. Visually, it employs a clean, top-down interface with a fixed, flip-screen layout—functional but unremarkable. The design prioritizes clarity over flair, ensuring that letters and gridlines remain legible even on smaller monitors. This minimalism suits the game’s cerebral nature, avoiding distractions from the puzzle at hand.

Sound design is sparse, likely due to the technical limitations of the era and platform. Mobile compatibility was considered, but HTML5 audio quirks meant that sound could not be guaranteed across all devices. The result is a near-silent experience, where the only “music” is the player’s own thought process.

The absence of elaborate art or sound is not a detriment; rather, it reinforces the game’s identity as a pure logic puzzle. The world of Wordoku is one of mental space, where the only landscapes are the grids players construct and deconstruct in their minds.

Reception & Legacy

Critically and commercially, Wordoku left little trace. MobyGames lists no critic or user reviews, and Metacritic shows no scores—suggesting the game slipped under the radar of mainstream gaming press. This obscurity is telling: in 2009, the puzzle game market was saturated, and Wordoku’s CD-ROM format likely limited its reach in an increasingly digital world.

Yet, the game’s core concept—Sudoku with letters—has proven influential. Variants like Word Roundup Sudoku and Scramblets have since explored similar territory, blending word and number puzzles. Wordoku’s diagonal word mechanic, in particular, has been echoed in later designs that use hidden words or phrases as both clues and rewards.

Its legacy is that of a quiet innovator: a game that took a global phenomenon and localized it for a specific audience, adding a layer of linguistic challenge that prefigured later hybrid puzzles. While it may not have achieved widespread fame, Wordoku occupies a niche in the history of puzzle games as an early experiment in cross-modal cognition.

Conclusion

Wordoku is not a game that will set the world on fire. It lacks the narrative ambition of story-driven titles, the visual spectacle of modern blockbusters, or even the widespread recognition of its numerical cousin. But in its restraint lies its charm. It is a game for the patient, the methodical, the lovers of logic and language alike.

In the broader tapestry of video game history, Wordoku is a modest thread—a reminder that sometimes, the most profound innovations come not from grand gestures, but from subtle twists on the familiar. It stands as a testament to the enduring appeal of Sudoku, and to the endless possibilities that arise when we dare to replace numbers with letters, and grids with words.

For those who seek a challenge that exercises both sides of the brain, Wordoku remains a worthy, if overlooked, companion. Its place in history is not as a revolution, but as a quiet evolution—one that continues to inspire puzzle designers to this day.