- Release Year: 1983

- Platforms: Windows, ZX Spectrum

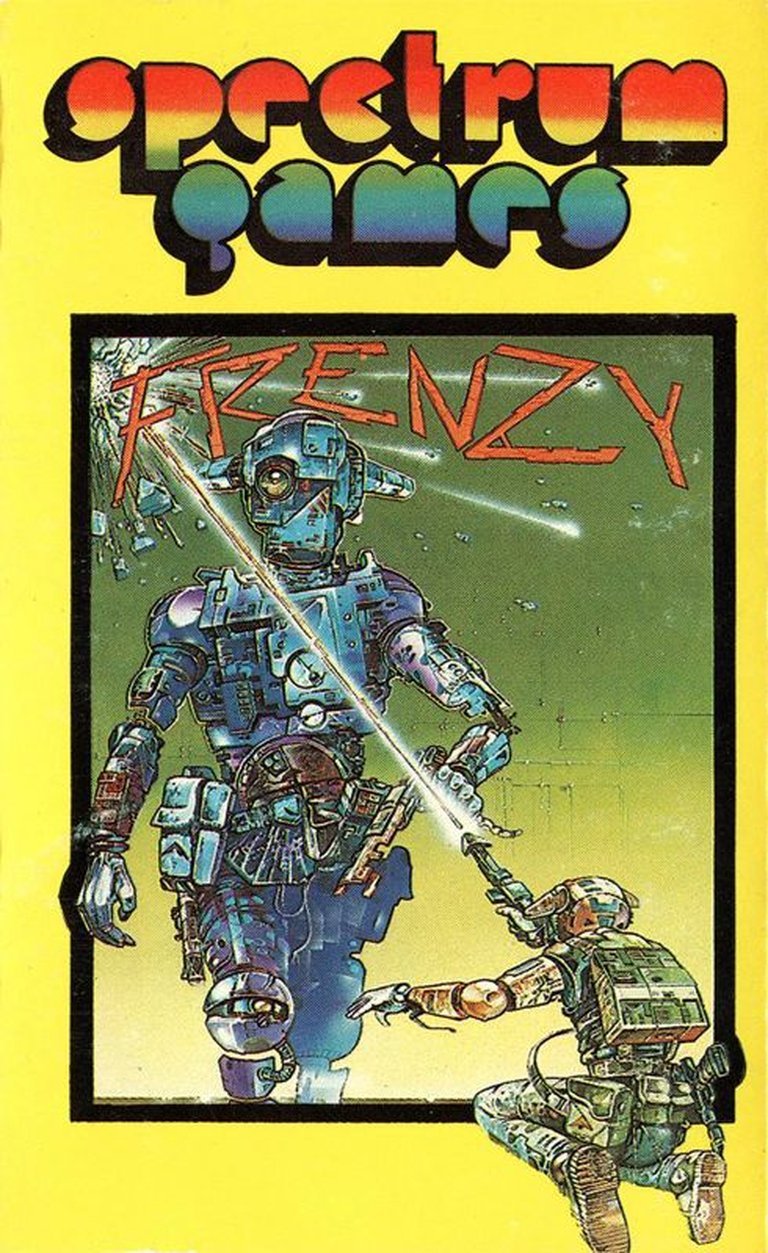

- Publisher: Pixel Games UK, Spectrum Games Limited

- Developer: Adrian Sherwin

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Shooter

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 83/100

Description

Frenzy is a sci-fi/futuristic multidirectional shooter game and sequel to Berzerk, where players navigate maze-like rooms filled with armed robots that must be shot to survive, while avoiding the relentless pursuit of Evil Otto—a bouncing, indestructible smiley face that appears if the player lingers too long. The game features labyrinthine scenery with lethal walls, increasing robot threats over time, and no ending beyond losing all lives.

Where to Buy Frenzy

PC

Frenzy Guides & Walkthroughs

Frenzy: Review

Introduction

In the pantheon of 1980s arcade classics, few titles capture the relentless tension and mechanical dread of Berzerk (1980). Its sequel, Frenzy (1982), emerged as both an evolution and a refinement of Alan McNeil’s original vision—a multidirectional shooter where survival in a labyrinth of killer robots was a feat of reflexive genius. While it never achieved the iconic status of its predecessor, Frenzy deserves scrutiny as a masterclass in distilled arcade design. This review examines Frenzy not merely as a footnote in gaming history, but as a meticulously crafted experience that amplified the intensity of its predecessor while introducing systemic depth. Its legacy lies in how it refined the “survivalist shooter” template, proving that even subtle innovations could redefine a genre.

Development History & Context

Stern Electronics tasked Alan McNeil, the architect of Berzerk, with designing its sequel. McNeil’s prior experience with sequels at Dave Nutting Associates (e.g., reworking Gun Fight and Boot Hill) equipped him to avoid a simple rehash. Running on the same Z80 microprocessor as Berzerk (2.5 MHz), Frenzy operated within technological constraints but leveraged hardware innovations like a custom LPC speech chip ($1,000 per word) for synthesized dialogue. Released in May 1982, it arrived during arcade’s golden age—a market saturated with shooters like Robotron: 2084 and Dig Dug. Stern’s business model favored rapid, high-impact coin-ops; Frenzy cabinets featured patented front-access drawers for easy maintenance and distinctive orange aesthetics. The game’s ports followed swiftly: ColecoVision (1983) and ZX Spectrum (1983), with the latter being an unofficial variant by David Shea. In 2023, Atari’s acquisition of Stern’s IP (including Frenzy) cemented its place in retro revivals, culminating in a 2024 official Atari 7800 release.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Frenzy eschews overt storytelling in favor of atmospheric dread. The player embodies a lone “Humanoid” (or “Commando” in manuals) trapped in a sentient maze, hunted by robots programmed with chillingly simple directives: “The humanoid must not destroy the robot.” The narrative emerges through environmental storytelling and robotic dialogue. Unlike Berzerk’s chatty bots, Frenzy’s robots speak sparingly:

– “Robot attack!” signals Evil Otto’s arrival.

– “Charge attack shoot kill destroy” echoes after Otto’s death, a mantra of mechanized rage.

– “A robot is not a chicken” and “A robot must get the humanoid” (sporadically from the Robot Factory) highlight robots’ flawed logic.

Evil Otto, renamed “Crazy Otto” in lore, is the game’s thematic centerpiece. Named after Stern’s security head Dave Otto—a figure who smiled while reprimanding employees—his smiling visage embodies corporate bureaucracy’s insidious cruelty. His vulnerability (three shots to kill) and escalating speed create a cycle of oppression: defiance only strengthens the system. The Big Otto statue in every fourth maze symbolizes authoritarian oversight, its enraged eyes glowing when Otto is killed, mirroring the state’s retaliation against rebellion. Thematically, Frenzy is a parable of futility: the maze is an inescapable system, and the player’s victories are temporary respites from inevitable annihilation.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Frenzy’s gameplay loop is a symphony of lethal geometry. Players navigate rooms via cardinal exits, with the entryway sealing behind them. Mechanics evolved from Berzerk:

– Walls: Destructible “dot” walls can be blasted into escape routes, while reflective white walls ricochet shots—enabling lethal traps where robots destroy themselves. Only closed doors absorb shots passively.

– Combat: Robots (skeletons and tanks) explode on death, threatening the player with splash damage. Skeletons’ thin sprites make vertical shots harder.

– Evil Otto: Now killable (3 shots transform him from smiley → neutral → frowny → death), but respawns faster. His persistence embodies the game’s sadistic escalation.

– Special Rooms: Every fourth maze introduces interactive elements:

– Big Otto: Killing Otto spawns four additional Ottos if the statue’s eyes glow.

– Power Plant: Disabled by a shot, freezing robots.

– Central Computer: Shot to trigger chaotic robot movement (walls become lethal).

– Robot Factory: Spawns endless robots until disabled (ColecoVision port only).

The ColecoVision port enhanced playability with more frequent extra lives (at 1,000 points) and adjustable skill levels. Yet Frenzy’s difficulty curve remains steep: robot counts escalate, and Otto’s speed increases exponentially, demanding pixel-perfect navigation. Its brilliance lies in emergent strategy—using wall physics to bottleneck robots or exploiting room-specific mechanics—though the ZX Spectrum port (by David Shea) diluted this with simplified enemies and indestructible “sphere” pursuers.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Stern’s monochrome visuals were augmented by a color overlay board, bathing mazes in stark blues, yellows, and oranges. The aesthetic is industrial dystopia: jagged corridors and robotic sprites evoke a decaying cyberpunk labyrinth. Evil Otto’s bouncing smile contrasts grotesquely with the skeletal robots, while special rooms like the Power Plant’s dynamos or the Central Computer’s reel-to-reel design inject sci-fi verisimilitude.

Sound design is Frenzy’s auditory terror. The LPC chip delivers robotic taunts (“The humanoid…”) and Otto’s rhythmic thudding. Explosions and ricochet shots create a cacophony of violence, while the ColecoVision port’s silence amplifies tension. The arcade’s pull-out drawer design—allowing board swaps—reflects the game’s modular philosophy: each room is a self-contained puzzle box.

Reception & Legacy

Frenzy was critically lauded but commercially overshadowed by Berzerk. Electronic Games deemed it “a good follow-up,” praising its refined mechanics, while Computer Entertainer lauded the ColecoVision port’s addictive gameplay. However, its heightened difficulty alienated casual players. Ports varied: the ZX Spectrum version was a stripped-down “unofficial” imitation, while the ColecoVision release (by Davis & Nussrallah & Associates) was praised for its faithful adaptation and smoother difficulty curve.

Legacy-wise, Frenzy influenced shooters like Robotron through its emphasis on environmental tactics and AI manipulation. Its IP acquisition by Atari in 2023 spurred modern re-releases, including Robert DeCrescenzo’s 2013 homebrew 7800 version—now officially sold via AtariAge. Yet its most profound impact lies in its design philosophy: Frenzy proved that sequels could deepen complexity without compromising accessibility, setting a template for genre refinement.

Conclusion

Frenzy is a testament to Alan McNeil’s design genius—a game that turned constraints into opportunities. It amplified Berzerk’s tension with mechanical depth: destructible walls, reactive robots, and the ever-escalating threat of Crazy Otto created a survival experience that was both punishing and exhilarating. Though its ports varied and its popularity faded, Frenzy’s legacy endures in its systemic elegance. It stands not as Berzerk’s shadow but as its evolutionary equal—a perfectly distilled arcade experience where every shot, every wall, and every bounce of Otto’s face is a lesson in calculated defiance. In the annals of gaming history, Frenzy is less a sequel and more a refinement—a vital chapter in the story of how simple mechanics can yield infinite, heart-pounding tension.