- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Kids Interactive

- Developer: Kris Jamsa

- Genre: Educational

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Educational, Interactive story, Paddle game, Point-and-click, Shape Matching

- Setting: Bedtime, Children’s, Dreams

Description

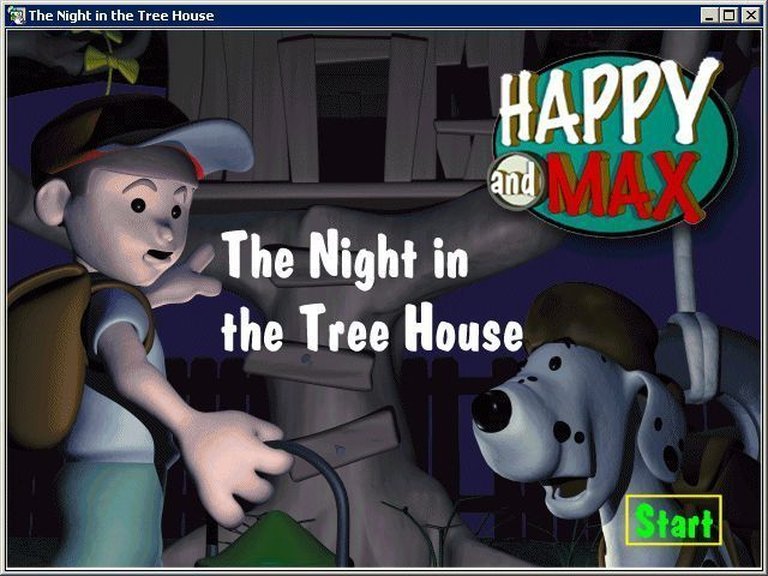

Happy & Max: The Night in the Tree House is an interactive storybook for young children featuring a boy named Max and his dog Happy. The game displays illustrated pages with rhyming couplets read aloud, alongside interactive hotspots that trigger sound effects or additional images. It includes two educational mini-games: ‘Dream Pong,’ where Max must defeat Happy in a Pong clone to overcome his fear of sleep, and ‘Shadow Match,’ requiring players to identify objects by matching them to their shadows to help the characters rest in their tree house. Success in the games is rewarded with ‘Well Done’ messages, and the storybook’s audio can also be played on a standard CD player.

Happy & Max: The Night in the Tree House: A Digital Campfire for the Preschool Generation

Introduction

In the nascent days of mainstream personal computing, when CD-ROMs represented the cutting edge of interactive media, a curious artifact emerged: Happy & Max: The Night in the Tree House. Released in 1998 by Kids Interactive, this educational title stands as a charming, if understudied, relic of an era when edutainment was rapidly evolving beyond simple drill-and-practice software. More than just a game, it was a multimedia storybook experience designed to bridge the gap between traditional print literature and digital interaction for preschoolers. This review delves into the historical context, narrative mechanics, and technological underpinnings of Happy & Max, arguing that its simplistic design belies a profound understanding of early childhood learning principles. As we unpack its layered components—from its rhyming narrative to its rudimentary minigames—we uncover a title that, while technologically modest by today’s standards, remains a fascinating case study in targeted, age-appropriate game design.

Development History & Context

Happy & Max: The Night in the Tree House emerged during a pivotal moment in both the gaming and educational software industries. By 1998, the Windows 95/98 platform had firmly established itself, making CD-ROMs the dominant medium for rich multimedia experiences. The educational software market, buoyed by the “edutainment” boom of the mid-90s, was saturated with titles from studios like Humongous Entertainment (known for Putt-Putt and Freddish Fish) and The Learning Company (famous for Reader Rabbit and Carmen Sandiego). Within this competitive landscape, Happy & Max carved a niche as an intimate, low-budget production.

The project was the brainchild of Kris Jamsa, a tech author and entrepreneur whose Jamsa Press imprint published numerous computer-related books. The title’s genesis reveals its unique pedigree: Happy and Max were not fictional characters but Jamsa’s own pets—a Dalmatian (Happy, whose likeness graced the cover) and a German Shepherd (Max). This personal connection imbued the project with authenticity, transforming a commercial venture into a labor of love. Technologically, the game was constrained by the era’s capabilities. Running on Windows with minimal system requirements, it utilized fixed, flip-screen visuals—a deliberate choice to avoid taxing early PCs. Its production was lean, with Jamsa handling all copyright and design duties, reflecting the “one-person studio” ethos common in small-scale educational software. This context is crucial: Happy & Max was never intended to compete with AAA titles; instead, it aimed to be a polished, accessible tool for introducing preschoolers to basic literacy and mouse skills within the cozy, familiar framework of a bedtime story.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The core of Happy & Max revolves around a deceptively simple narrative: a boy (Max) and his dog (Happy) spend a night in a treehouse. The story unfolds as a series of illustrated “pages,” each accompanied by rhyming couplets read aloud by a narrator. This structure masterfully achieves two pedagogical goals: fostering auditory comprehension through rhythmic verse and reinforcing word recognition via synchronized text and audio. The rhymes are crafted with preschool phonetics in mind—simple, repetitive, and bursting with onomatopoeia. For example, lines like “The moon is bright, the stars are out, / Max and Happy start to shout!” deliver both plot advancement (their excitement) and linguistic patterns (short vowel sounds, consonant clusters).

The narrative progresses through incremental, interactive discovery. Each page features 1-2 “hotspots”—hidden areas on the screen that trigger secondary animations or sound effects when clicked. Clicking a cricket might make it chirp; tapping a lantern could illuminate the treehouse. These interactions are thematically coherent: they reward curiosity and reinforce the idea that stories are living, responsive entities. The dual protagonists—Max (the cautious child) and Happy (the exuberant dog)—provide relatable archetypes. Max embodies common childhood anxieties (e.g., fear of the dark), while Happy serves as a playful foil. Their dynamic subtly addresses themes of courage and companionship: when Max hesitates, Happy’s enthusiasm nudges him forward. The climax, featuring a “treehouse monster” (revealed to be benign), is a masterclass in age-appropriate tension-building, resolving not with confrontation but with reassurance—a vital lesson for preschoolers navigating imaginary fears. The narrative’s brilliance lies in its economy: every element, from the rhyme scheme to the hotspots, serves a dual purpose of storytelling and skill development.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Happy & Max deploys three distinct gameplay modules, each targeting specific developmental milestones:

-

Interactive Storybook: This is the primary mode, functioning as a “point-and-click” narrative experience. The core mechanic is hotspot discovery, honing fine motor skills and spatial awareness. The interface is minimalist: a cursor changes to a hand over interactive elements, providing intuitive feedback. Progression is linear—children advance by clicking arrows to “turn pages”—yet the hotspots allow for nonlinear exploration within a fixed scene. This structure balances guided learning with autonomy. The inclusion of audio narration in a CD-player-compatible format was a forward-thinking feature, allowing the story to be enjoyed independently of the computer.

-

Dream Pong: A whimsical take on the classic Pong arcade game, this minigame contextualizes skill-building within the narrative. Max, fearing bad dreams, challenges Happy to a game of Pong as a sleep aid. The gameplay is a single-player paddle game controlled via mouse, where the player bounces a ball to prevent it from reaching their side. Its educational value lies in hand-eye coordination and basic physics comprehension. While rudimentary by modern standards, the difficulty is perfectly calibrated for preschoolers—slow ball speed, forgiving paddle size, and immediate “Well Done!” rewards upon success. Its integration into the story reinforces emotional resilience: conquering the game symbolizes conquering fear.

-

Shadow Match: This minigame directly targets object recognition and deductive reasoning. Max and Happy, spooked by shadows in the treehouse, require the player’s help to identify objects by matching them to their silhouettes. The interface presents a shape on one side and potential objects on the other. Correct matches elicit positive audio/visual feedback. It teaches pattern recognition, spatial relationships, and vocabulary (e.g., distinguishing a “squirrel” from a “leaf”). The “Well Done” message serves as positive reinforcement, a key principle in early childhood education.

These systems are unified by a cohesive philosophy: gameplay must feel like play, not work. There are no failure states, no complex stats, no penalties. Progress is measured in smiles and moments of discovery, making Happy & Max a paragon of “failure-free” design.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The world of Happy & Max is a masterclass in environmental storytelling for young audiences. The treehouse setting is rendered in a warm, folk-art style—soft, rounded shapes, a muted color palette dominated by blues (night sky), browns (wood), and yellows (lantern light). The fixed-screen visuals create a series of intimate, tableaux-like scenes: a moonlit canopy, cluttered interiors with toys and books, glimpses of wildlife. This “flipping” between static screens evokes the turning of a physical book, grounding the digital experience in a familiar tactile metaphor. The art direction prioritizes clarity and emotional warmth over realism; characters are expressive with large, simple faces, while environmental details (e.g., a swaying branch, a twinkling firefly) invite interaction.

Sound design is equally critical. The rhyming narration is delivered with a gentle, sing-song cadence, reminiscent of a parent reading at bedtime. Sound effects are sparse but purposeful: a cricket’s chirp, a dog’s bark, a creaking floorboard. These are not meant to be realistic but to evoke a mood—coziness, gentle mystery, or playful surprise. The absence of jarring audio ensures the experience remains soothing. The Dutch release, titled Happy en Max – De Boomhut, confirms the universality of its visual and auditory appeal, suggesting the design transcended cultural barriers. Together, the art and sound create a sanctuary—a digital campfire that envelops the child in a safe, imaginative space.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its 1998 release, Happy & Max: The Night in the Tree House operated in the shadow of more prominent edutainment franchises. Unlike Reader Rabbit or Carmen Sandiego, it garnered minimal mainstream media attention. Commercial data is scarce, but its presence on secondhand markets (eBay, AbeBooks) and in educational archives (like the Nationaal Archief Educatieve Games in the Netherlands) suggests it enjoyed a modest, geographically limited circulation—particularly in the Netherlands via Bruna Multimedia. Its legacy is thus less one of commercial impact than of cultural preservation.

Critically, it remains an understudied artifact. The absence of reviews on platforms like MobyGames and Metacritic highlights the niche status of such specialized titles. Yet, its influence can be inferred indirectly. Its hybrid book-game format presaged modern interactive e-books and apps, while its “failure-free” minigames foreshadowed the trend toward skill-building embedded in narrative contexts. Historically, it documents the democratization of game development; Jamsa’s one-man operation proved that meaningful educational experiences could be created without massive teams or budgets. Today, it survives as a charming time capsule—a reminder of a time when innovation in edutainment was often small in scale but grand in intention. Its enduring appeal lies in its authenticity: born from a personal story and crafted with genuine affection for its audience.

Conclusion

Happy & Max: The Night in the Tree House is far more than its simple premise suggests. It is a meticulously crafted digital fable, a product of its time that speaks volumes about the intersection of technology, education, and childhood. Its strengths lie in its unwavering focus on its target audience: every element, from the rhyming narrative to the forgiving minigames, is calibrated to engage, reassure, and subtly educate preschoolers. While its technological constraints are evident today, its design philosophy—prioritizing discovery over difficulty, narrative over mechanics—remains profoundly relevant.

In the grand tapestry of video game history, Happy & Max occupies a unique niche. It is not a landmark title that revolutionized the industry, nor is it a forgotten masterpiece. Instead, it is a vital artifact—a window into a period when edutainment was exploring new frontiers of interactivity. Its legacy is preserved in the quiet joy it brought to young users and in its role as a testament to the power of personal passion in design. For historians and educators alike, Happy & Max: The Night in the Tree House endures not as a game to be played for competitive thrills, but as a digital campfire—a warm, inviting space where stories come alive, and learning feels like play.