- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: BrainGame Publishing, GmbH, HEUREKA-Klett Softwareverlag GmbH, tewi publishing GmbH

- Developer: Ruske & Pühretmaier Edutainment GmbH

- Genre: Adventure, Educational

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Puzzle elements

- Setting: History

- Average Score: 69/100

Description

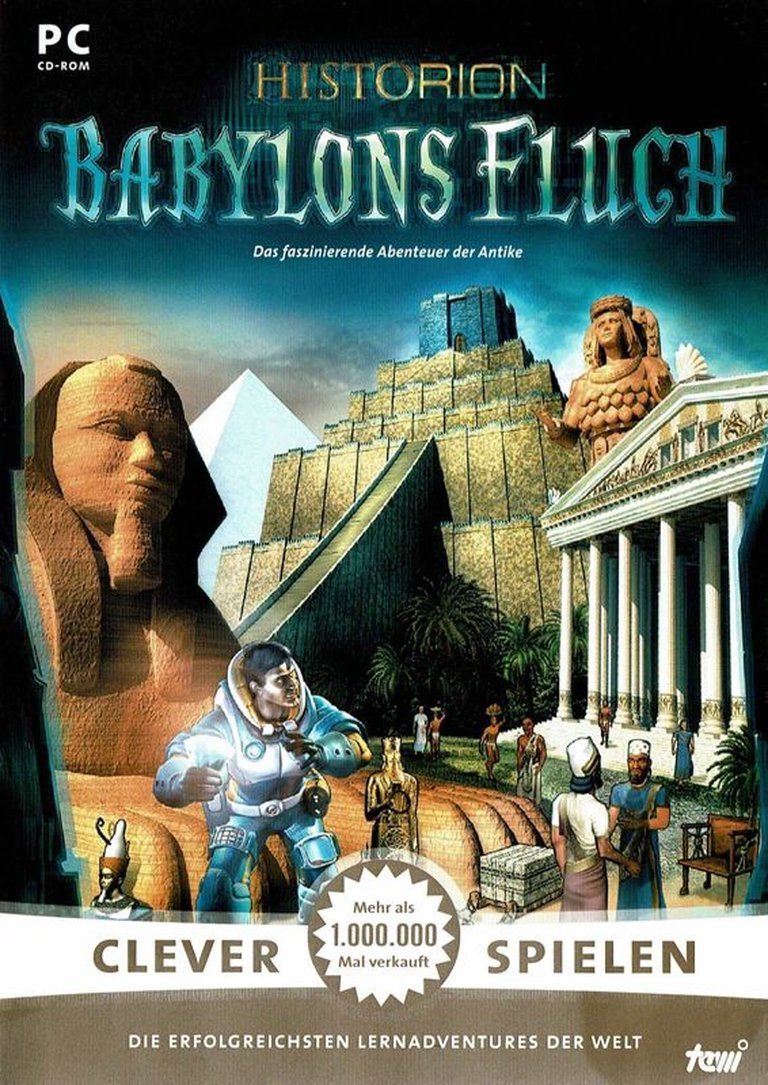

Historion: Babylons Fluch is the sequel to Historion, where players must prevent demons revived by computer viruses from destroying humanity’s history by traveling through time to solve riddles and puzzles at iconic ancient sites like the Pyramids of Giza, the Temple of Ephesos, and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, while learning about architecture, religion, society, and politics of these eras.

Historion: Babylons Fluch: A Pillar of Edutainment’s Golden Age

Introduction

In the crowded landscape of early 2000s educational gaming, few titles dared to blend deep historical immersion with genuine adventure mechanics. Historion: Babylons Fluch stands as a bold, if flawed, testament to that ambition. Released in 2003 by German developer Ruske & Pühretmaier Edutainment GmbH and published by a consortium including HEUREKA-Klett and BrainGame Publishing, this sequel to the 2002 title Historion transports players on a perilous journey through antiquity. Its premise is both grand and timely: computer viruses have revived ancient demons, threatening to unravel the very fabric of human history. As Tom, a mechanic from the future, players must time-travel to pivotal moments in the past—Babylon, Giza, Ephesus—solving intricate puzzles, engaging with historical figures, and battling manifestations of evil to preserve our collective heritage. This review will argue that Babylons Fluch succeeds remarkably in making history tangible and engaging for a younger audience, despite significant technical limitations and a reliance on formulaic design inherited from its predecessor. It represents a fascinating, if niche, artifact of a genre where education and adventure walked hand-in-hand.

Development History & Context

Historion: Babylons Fluch emerged from the specific crucible of German educational software development in the early 2000s. The developer, Ruske & Pühretmaier Edutainment GmbH, operated within a niche market known for prioritizing pedagogical value above cutting-edge spectacle. This context is crucial; the game wasn’t conceived to compete with AAA releases but to fulfill a distinct educational mandate. Project Lead Axel Ruske and his team, including a dedicated historical research unit (Susanne Patzelt and Volker Schick), aimed to create a “time machine” that felt authentic. Technologically, the game was a product of its era. It utilized the proprietary gxEngine for 3D rendering and relied on Bink Video middleware for its cutscenes, common choices for mid-budget titles aiming for visual polish without the prohibitive costs of proprietary engines. The technical constraints are evident: minimum requirements included a Pentium III 450MHz, 128MB RAM, and an OpenGL-compatible 3D card with a mere 16MB VRAM. This places it firmly in the realm of games accessible to school computers and mid-range home PCs of the time.

The gaming landscape in 2003 was dominated by the rise of 3D adventures and the burgeoning MMORPG genre in the West. Germany, however, maintained a strong tradition of point-and-click and edutainment games. Babylons Fluch occupied this fertile ground. It positioned itself clearly within the “Quest for Knowledge” series (its predecessor Historion was the first), alongside titles like Physicus: Die Rückkehr and Geograficus. This series identity emphasized a core philosophy: learning should be an active, exploratory adventure. The development team, numbering 28 individuals according to the credits, handled diverse aspects meticulously—from 3D design of antiquities (Fikret Yildirim, Gereon Zwosta) and character design (Christoph Kucher, Dennis Böcklin) to sound design (m.u.k.e., Marc Ruske, Jörg Maier-Rothe) and the critical historical content (Patzelt & Schick). The screenplay, penned by Carsten Kisslat, focused on weaving educational facts into dialogue and narrative, aiming for seamless integration rather than dry lectures. The release across multiple publishers (HEUREKA-Klett, BrainGame, tewi) reflects the collaborative, distribution-focused strategy common in this segment of the German market.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative of Babylons Fluch is a classic sci-fi/historical fusion, executed with a strong educational imperative. The core premise is high-concept yet accessible: a digital repository of human history, the “Historion,” is compromised by computer viruses. These viruses have resurrected the demon Anku from ancient Babylon, who now seeks to corrupt the historical record itself, threatening the foundations of human knowledge. To combat this existential threat, the player character, Tom, a mechanic from the future, is equipped with the technology for time travel. His mission is to journey back to pivotal moments in antiquity, locate legendary “magical stones” containing the knowledge to defeat Anku, and prevent historical catastrophe.

The game’s thematic depth lies in its unwavering focus on history as a living, tangible force. Unlike many educational games that present facts statically, Babylons Fluch immerses the player in reconstructed environments where history is active and immediate. The narrative framework allows the developers to seamlessly integrate educational content: dialogue with historical figures (like Nebukadnezar in Babylon), descriptions of daily life, architectural marvels, religious practices, and technological innovations become essential puzzle clues and world-building elements. The themes explored include:

- The Fragility of Knowledge: Anku’s attack represents the peril of losing historical understanding, emphasizing the game’s core educational message.

- Cultural Syncretism: Traveling between Egypt, Babylon, and Greece highlights different worldviews and practices, encouraging comparison and understanding.

- Human Ingenuity: The puzzles often revolve around solving problems using the knowledge and technology of the era, showcasing ancient innovation (e.g., pyramid construction techniques, the invention of soap in Babylon).

- Mythology vs. Reality: The presence of demons and supernatural threats provides a fantastical layer, while the core interactions and environments strive for historical accuracy within the constraints of the narrative.

The plot structure follows a linear, episodic journey. Tom begins in ancient Babylon, encountering Nebukadnezar and exploring the Hanging Gardens. He then travels to Egypt to witness the construction of the pyramids at Giza, and finally to the Temple of Artemis in Ephesos. Each location presents a distinct chapter in the story, populated by NPCs (priestesses, handcrafters, merchants, pilgrims) who provide both clues and historical context. The dialogue, penned by Carsten Kisslat, serves a dual purpose: advancing the plot and disseminating information. While the overarching narrative of “stop the demon” provides a clear goal, the substance lies in the historical vignettes. As noted by the Adventurearchiv review, the game “can of course only scarify the historical surface,” but it does so effectively “in a very entertaining, occasionally also exciting way.” The “living scenes” and “reconstructions of the antique places” are central to making this surface-level history engaging. The character of Anku, the Babylonian demon, remains somewhat abstract as the primary antagonist, serving more as a narrative device to justify the time-travel premise than a deeply developed villain. The true “characters” are the civilizations themselves, brought to life through the player’s interactions and the meticulously researched environments.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Historion: Babylons Fluch is fundamentally a 3rd-person adventure game with puzzle-solving elements and light action/combat. As Tom, players navigate expansive, pre-rendered 3D environments viewed from a fixed perspective, emphasizing exploration and interaction over traditional camera control. The core gameplay loop involves:

- Exploration & Dialogue: Players move through historically themed locations (marketplaces, temples, construction sites). Interaction with the environment and NPCs is key. Dialogues, often voice-acted in German, provide crucial information, historical context, and puzzle clues. The game encourages talking to everyone, as even minor characters might offer vital insights or trigger events.

- Puzzle-Solving: This is the heart of the adventure. Puzzles are integrated into the environment and narrative. Examples include deciphering ancient scripts based on cultural knowledge, manipulating architectural elements (aligning stones in Babylon, navigating pyramid chambers), using tools discovered in one era in another, and solving environmental riddles tied to daily life or rituals. According to the Adventurearchiv review, the puzzles are “relative easy,” a deliberate choice to “allow more room for historical information” and make the game accessible, especially for beginners. This contrasts with the potentially frustrating complexity of some contemporaneous adventure titles.

- Combat: The game features an “unblutiger Kampf” (bloodless combat) system. Encounters primarily involve magical manifestations of Anku’s influence or mythological creatures. Combat is simplified, often involving timed button presses or strategic positioning rather than complex combos or resource management. Critically, the Adventurearchiv review notes “noticeable improvements in handling and mitigation of the fights” compared to the first Historion, contributing to the higher score. This suggests combat was a point of weakness in the original that was addressed, though it remains a minor, non-violent distraction rather than a core feature.

- Resource Management: A subtle layer involves managing Tom’s “Nahrungs- und Kraftreserven” (food and energy reserves). This requires the player to periodically find sustenance or rest points, adding a slight layer of realism and encouraging exploration to maintain resources, though it doesn’t appear to be overly punitive or central to progression.

The User Interface (UI) was typical for the era, likely featuring an inventory system, dialogue options, and perhaps a simple status display for resources and objectives. The “handling improvements” mentioned in the review likely refer to smoother movement, more intuitive interaction with hotspots, and a less cumbersome inventory system compared to its predecessor. The game’s educational content is seamlessly woven into these systems – knowledge gained from dialogues or environmental observation becomes the key to unlocking new areas or solving puzzles. For instance, understanding the difference between Doric and Ionic columns (taught in the game) might be essential to progress in the Ephesos temple section. While the basic framework is inherited from Historion, the changes to puzzle design and combat smoothness represent an iterative refinement aimed at improving player flow and accessibility within the established educational adventure template.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The most striking achievement of Historion: Babylons Fluch lies in its ambitious world-building and visual direction. The development team, led by 3D designers Fikret Yildirim, Gereon Zwosta, and Vladan Subotic, undertook the monumental task of recreating iconic ancient locations with considerable detail. The game transports players to the Hanging Gardens of Babylon (complete with terraces and exotic flora), the Pyramids of Giza during their construction (showing ramps, workers, and the scale of the endeavor), and the Temple of Artemis in Ephesos (depicting its grandeur and pilgrims). These aren’t static backdrops; they are bustling, living environments. Marketplaces teem with vendors and customers, temples echo with rituals, and construction sites show the logistical marvels of ancient engineering. This commitment to “living scenes” (lebende Szenen) is repeatedly praised as a key strength, making history feel immediate and immersive.

The art direction balances historical authenticity with the needs of a 3D adventure game. Character design (Christoph Kucher, Dennis Böcklin) aims for plausible representations of ancient Egyptians, Babylonians, and Greeks, avoiding cartoonish exaggeration while remaining visually distinct. The environments utilize the gxEngine to create atmospheric lighting and architectural details – the imposing scale of the pyramids, the intricate stonework of the Artemision. While the technology of 2003 limits texture resolution and polygon count, the artistic intent to evoke the awe and grandeur of these wonders largely succeeds. The visual language helps ground the fantastical premise of demons and time travel in a tangible historical reality. The 2D design (Susanne Schwalm) and illustrations (Sebastian Erb, Bernhard Speh) likely support menus, inventory items, and perhaps concept art, maintaining a cohesive aesthetic.

The sound design is another critical component of the game’s atmosphere. The soundtrack, composed by André Abshagen, employs orchestral and ethnic-inspired melodies to evoke the mood of each ancient civilization – grand and powerful for Egypt, mysterious and exotic for Babylon, stately and reverent for Ephesos. Sound effects (m.u.k.e., Marc Ruske, Jörg Maier-Rothe) complete the immersion: the bustle of marketplaces, the clink of tools on stone, the rustle of leaves in the gardens, and the otherworldly sounds of demonic encounters. Voice acting, entirely in German (as per the game’s regional focus and educational market), brings the NPCs and Tom to life. While the quality might vary by modern standards, the use of native voice acting is essential for authenticity and accessibility within the target German-speaking audience. The combination of evocative visuals, period-inspired music, and ambient sound effectively transports the player, making the “history to touch and experience” (Geschichte zum Anfassen und Miterleben) a tangible reality within the technological constraints of the time.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its release in late 2003, Historion: Babylons Fluch received a modestly positive critical reception, primarily within the German-speaking adventure and educational gaming press. The sole quantifiable score available is 78% from Adventurearchiv, reviewed in January 2004. This review highlights the game’s core strengths: its “very entertaining, occasionally also exciting” presentation of historical facts, the “great” reconstructions of ancient sites, the “more detailed story” compared to the first game, and the accessibility provided by “relative easy” puzzles. The reviewer explicitly praises the “noticeable improvements in handling and mitigation of the fights,” suggesting the sequel addressed key weaknesses of its predecessor. The estimated 12-14 hour playtime was noted as being driven more by exploration and combat than complex puzzles. The verdict was clear: it was a game that would interest those passionate about history, presented in a wonderfully accessible way, especially for beginners. Within the niche of German edutainment, this was a respectable score, signaling a successful refinement of the formula.

Commercial reception data is scarce, typical for mid-budget European titles of this era. Its presence on platforms like AbandonWiki and Old-Games.ru indicates a lasting, if modest, presence among collectors and fans of educational/adventure hybrids. However, its lack of widespread international distribution and the language barrier (German only) limited its broader market impact.

The legacy of Babylons Fluch is intrinsically tied to its place within the “Quest for Knowledge” series and the broader output of Ruske & Pühretmaier/Braingame Publishing. It represents a significant step in refining their edutainment formula, particularly in terms of player experience (handling, combat). Its greatest legacy lies in demonstrating the viability of integrating deep historical content into an accessible adventure framework. The meticulous recreation of ancient sites, while simplified, provided valuable visual context for learners. It sits alongside titles like Physicus (science), Geograficus (geography), and Chemicus as part of a concerted effort to make complex subjects engaging through interactive storytelling.

However, its legacy is also tempered by criticism. The review on Old-Games.ru is notably harsh, describing it as a “reworking” (переделка) and “essentially a mod” of the first Historion with “absolutely no changes” to the interface and even “copied” locations like the combat training lab. While acknowledging some educational value and unique settings (Babylon), the reviewer condemns the “self-copying” approach as “very disappointing,” assigning a middling score as a result. This criticism highlights a potential flaw in the series’ iterative strategy: prioritizing proven mechanics over innovation. Despite this, the game’s survival on preservation sites and its inclusion in series discussions affirm its status as a recognizable, if niche, artifact of early 2000s edutainment. Its influence is less seen in direct clones and more in the ongoing, albeit niche, tradition of educational adventure games that prioritize historical immersion over pure spectacle.

Conclusion

Historion: Babylons Fluch stands as a fascinating and ambitious product of its time and place, embodying the strengths and limitations of early 2000s German edutainment. As a sequel, it successfully refines the core formula of its predecessor, offering smoother controls, more accessible puzzles, and improved combat, leading to a more enjoyable player experience as noted by contemporary critics. Its greatest triumph lies in its world-building and educational integration. The meticulous recreation of ancient Babylon, Egypt, and Ephesus, combined with the seamless weaving of historical facts into dialogue and puzzles, creates an experience that genuinely makes history tangible and engaging for its target audience. The “living scenes” and atmosphere, supported by competent art direction and evocative sound design, successfully transport players, fulfilling the promise of “history to touch and experience.”

However, the game is undeniably a product of its constraints. Technologically limited by the era’s hardware, its 3D graphics, while atmospheric, lack the detail and fluidity of contemporary mainstream titles. More significantly, the criticism from Old-Games.ru highlights a fundamental issue: it leans heavily on the established framework of its predecessor, offering gameplay that feels more like a polished expansion pack than a truly innovative sequel. The reliance on reused interface elements and similar structural puzzles prevents it from achieving greater distinction. Its narrow German-language focus further restricts its broader historical impact.

Ultimately, Historion: Babylons Fluch earns its place in video game history as a commendable, if flawed, pillar of edutainment. It succeeded in its primary mission: to educate about ancient civilizations through an entertaining and accessible adventure. While it may not have broken new ground in terms of genre innovation or technological prowess, its dedication to historical authenticity and immersive world-building within an engaging gameplay loop remains noteworthy. For those seeking a window into ancient Egypt, Babylon, and Greece, or for historians of educational gaming, Babylons Fluch offers a valuable, if time-capsuled, journey. It is a testament to a specific vision where the goal was not just to play a game, but to step into the past.