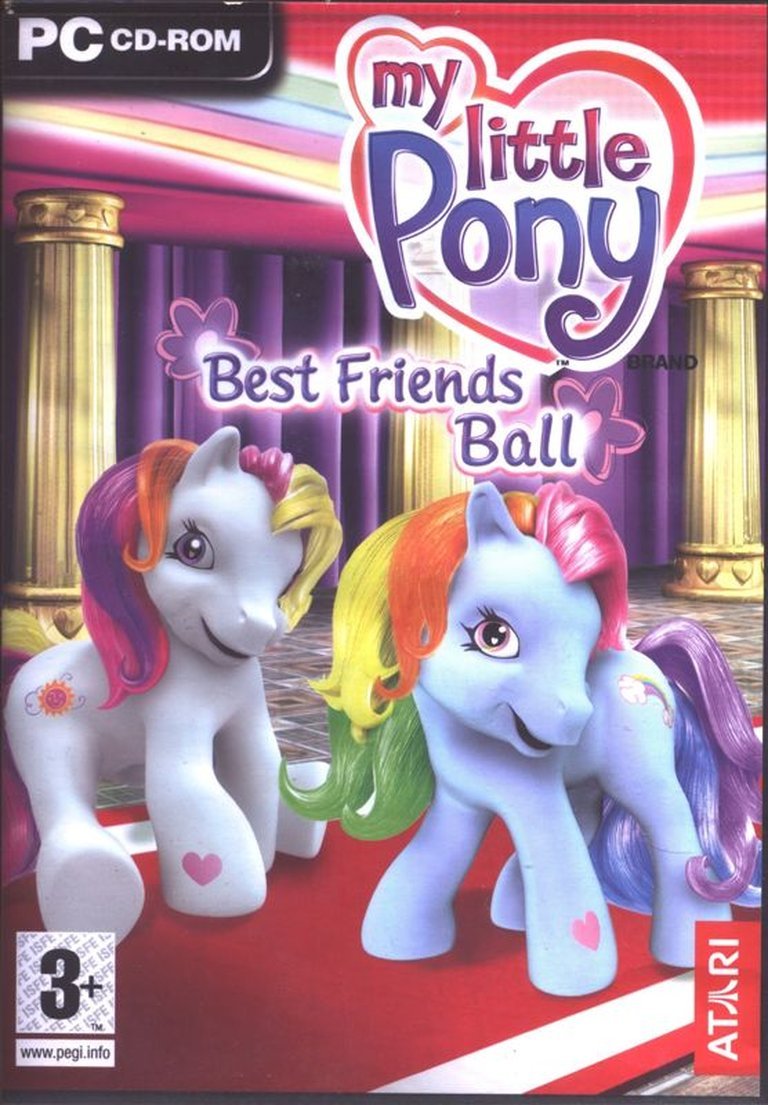

- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Atari Europe S.A.S.U., Atari Interactive, Inc., Global Software Publishing Ltd.

- Developer: ImaginEngine

- Genre: Simulation

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Crafting, Customization, Mini-games

- Setting: Fantasy

Description

Released in 2004 for Windows, My Little Pony: Best Friends Ball is a simulation game designed for young children based on the Generation 3 toyline. Set in the fantasy world of Ponyville, the objective is to help prepare for the Friendship Ball by selecting one of four ponies and completing a checklist of activities. Gameplay involves visiting distinct locations to engage in various mini-games, such as designing invitations at the Pony Cottage, choreographing dance moves at Twinkle Twirl’s stage, styling hair at the salon, and baking cakes at the cafe.

Gameplay Videos

My Little Pony: Best Friends Ball Guides & Walkthroughs

My Little Pony: Best Friends Ball: A Digital Friendship Ball of Nostalgia and Whimsy

Introduction

In the vibrant tapestry of licensed children’s entertainment, My Little Pony: Best Friends Ball occupies a uniquely niche yet historically fascinating space. Released in 2004 by Atari and developed by ImaginEngine, this PC-exclusive title stands as the second digital adaptation of the iconic franchise and the first to embrace the saccharine, pastel-hued aesthetic of Generation 3. As a game designed for the “Early Childhood” demographic, it eschews complex narratives or challenging gameplay in favor of a gentle, activity-driven adventure centered on community and creativity. Yet beyond its seemingly simplistic surface lies a product deeply rooted in the technological and cultural constraints of its era—a time when 3D graphics for young children were still experimental, and educational software often prioritized accessibility over innovation. This review argues that Best Friends Ball, despite its technical quirks and design limitations, represents a charming artifact of early 2000s licensed gaming, offering a window into the aspirations and compromises of developers aiming to translate beloved toy properties into interactive experiences. It is a digital love letter to childhood imagination, albeit one whose execution is as equally endearing as it is flawed.

Development History & Context

Best Friends Ball emerged from the collaborative efforts of ImaginEngine, a Massachusetts-based studio specializing in children’s interactive media, and Atari, leveraging its distribution network to capitalize on the resurgent popularity of the My Little Pony brand. The project was helmed by producer James Daly and executive producer Hudson Piehl, with Jennifer Fukuda overseeing brand management to ensure fidelity to Hasbro’s Generation 3 toyline—a departure from the earlier, more story-driven G1 and G2 eras. Vision-wise, the team sought to create a “play-with” rather than “play-as” experience, emphasizing collaborative creativity over character identification. This manifested in mechanics where players guide ponies as companions rather than avatars, a deliberate choice to mirror the toy’s role as a customizable plaything.

Technologically, the game was a product of its constraints. Released on CD-ROM for Windows 98/XP, it ran on modest hardware (Pentium II 300 MHz, 64MB RAM), necessitating lightweight 3D rendering and compressed audio. ImaginEngine employed a side-scrolling perspective to simplify navigation, a common tactic in children’s games of the era to avoid disorienting free-roaming mechanics. The gaming landscape in 2004 was dominated by edutainment titles like Dora the Explorer and SpongeBob SquarePants games, which balanced structured gameplay with educational goals. Best Friends Ball aligned with this trend but stood out for its laser focus on unstructured creativity—designing cakes, choreographing dances, and decorating spaces—reflecting the brand’s core ethos of self-expression. Yet its development was not without hiccups; internal documents from the Video Game History Foundation reveal beta builds from July 2004 and a gold master candidate by August 17, suggesting a tight timeline that may explain rushed elements like inconsistent textures and animation quirks. The inclusion of Adobe Acrobat Reader 6.0 for the manual underscores the era’s reliance on bundled software for accessibility, a reminder of the PC’s pre-streaming distribution challenges.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative of Best Friends Ball is a masterclass in minimalism, serving as a framework for gameplay rather than a driver. The plot is deceptively straightforward: the ponies of Ponyville are preparing for the Friendship Ball, a celebratory event where the baby pony Sparkleberry Swirl will be honored. The player, acting as a facilitator, must help their chosen pony (Sparkleworks, Pinkie Pie, Skywishes, or Sunny Daze) complete a checklist of tasks to ensure the ball’s success. This checklist—designing invitations, styling outfits, baking a cake, choreographing a dance, and assisting at least three other ponies—serves as the game’s narrative spine, transforming the story into a series of interconnected errands.

Characterization is deliberately archetypal, reflecting the toyline’s design. The four playable ponies embody distinct personalities: Pinkie Pie’s exuberant slowness (her voiceovers are notably slower, a quirk noted in fan wikis), Sparkleworks’ creative flair, Skywishes’ dreaminess, and Sunny Daze’s adventurous spirit. NPCs like the fashion-forward Amberlocks, the baker Cotton Candy, and the dancer Twinkle Twirl further populate this world, each representing a facet of community life. Crucially, the game breaks the fourth wall frequently; ponies address the player directly (“You can pick a different pony to play with!*”), reinforcing the “play-with” philosophy. This meta-commentary blurs the line between player and participant, framing the experience as collaborative storytelling.

Thematically, the game is an ode to friendship and communal effort. The Friendship Ball itself symbolizes unity, requiring collective contributions to unlock the Celebration Castle. Tasks like helping Fluttershy find a dream catcher kite or Desert Rose gather rainbowberries emphasize interdependence, while the customizable nature of invitations, cakes, and castle decorations celebrate individuality. Even the fetch quests—repetitive as they are—reinforce the idea that friendship is built on small, helpful acts. However, the narrative lacks emotional depth; the absence of conflict or character arcs reduces it to a pleasant but weightless simulation of cooperation, aimed squarely at teaching young players the value of helping others without delving into more nuanced lessons.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Best Friends Ball is a quintessential minigame compilation, structured around the player’s movement through the looped, side-scrolling hub of Ponyville. Core gameplay revolves around cycling between locations to complete checklist tasks, with each area housing a self-contained activity. This design ensures accessibility but risks monotony, as repetition becomes inevitable. The game’s most innovative mechanic is its “play-with” approach: players can switch between ponies at any time, allowing them to experience different perspectives and color schemes (e.g., Sunny Daze’s cottage has a blue rug, while Sparkleworks’ is pink). This fluidity, however, is undermined by the lack of progression; changing ponies merely alters aesthetics, not abilities or story.

The minigames themselves are a mixed bag. In the Pony Cottage, players design invitations by selecting backgrounds and stamps—a creative outlet with limited depth—then customize the cottage’s wallpaper, curtains, and bedding. Here, a UI flaw emerges: the close-up desk view shows fixed colors (e.g., a pink desk) regardless of the chosen pony, breaking immersion. Twinkle Twirl’s Dance Studio demands players drag exactly 12 dance moves into a sequence, a rhythm-based puzzle hampered by imprecise controls. Amberlocks’ Celebration Salon allows for pony customization (hairstyles, outfits, jewelry), but this aesthetic is only visible in the final photo booth—a baffling limitation. Cotton Candy’s Cafe simulates cake-making, with simple steps for baking and decorating, but its reliance on timed clicks feels arbitrary for the target age group.

Fetch quests, though mandatory for at least three ponies, are the weakest link. Players must find items like cupcakes or charms, guided by Rainbow Dash’s voiceovers. A critical flaw here is the inability to skip her initial instructions after starting a quest, forcing players to wait through repetitive dialogue. Pinkie Pie’s slower audio exacerbates this, making the game feel tedious for adults. The Celebration Castle finale offers redemption, allowing players to decorate the venue freely before the ball commences, culminating in a photo with Star Catcher. Yet, an unused voiceover suggests a planned certificate reward, highlighting unfinished ambitions.

UI design prioritizes simplicity: circular buttons dominate the interface, with voiceovers as the primary instruction method. While this aids literacy, the game’s heavy reliance on sound makes it inaccessible to deaf players—a significant oversight. Save systems are equally rudimentary, with progress vanishing on modern Windows systems, forcing single-session play. These systems, while functional, reflect a lack of polish, perhaps due to the rushed development timeline hinted at in archival builds.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Ponyville, the game’s setting, is a triumph of environmental storytelling. The side-scrolling loop—a design choice to prevent player disorientation—creates a cozy, self-contained world. Each location, from the thatch-roofed cottages to the grand Celebration Castle, feels distinct yet harmonious, fostering a sense of community. The world’s pacing is deliberately leisurely, with no time pressure, encouraging exploration. However, its simplicity borders on barrenness; beyond the key locations, Ponyville offers little to discover, a missed opportunity for deeper immersion.

Artistically, the game is a fascinating artifact of early 3D experimentation for children. As described in fan wikis, the ponies feature “felt-like” textures, a stylistic choice to mimic the plushness of toys. This creates an “uncanny” effect, where the models are soft and rounded but lack the polish of later titles. Cutscenes, notably the opening and castle entrance, are visibly pixelated, suggesting budget constraints. Environmental details are charming yet inconsistent: flora and fauna are colorful but static, while animations like the pony’s hair flipping during turns reveal technical limitations. The manual’s errors—e.g., mislabeled functions for the printer and ink quill—underscore the rushed production, though these quirks now add a layer of nostalgic charm.

Sound design is the game’s strongest asset. Voiceovers are omnipresent, guiding players through every interaction. Each pony has a distinct vocal tone, with Pinkie Pie’s slower delivery offering a unique, if frustrating, rhythm. The absence of background music is notable, but ambient sounds like rustling leaves or clinking cups create a lived-in atmosphere. Sound is not just aesthetic but functional; the game relies on it for instructions, making auditory cues integral to gameplay. Yet, this dependency is a double-edged sword, as the inability to skip audio during fetch quests highlights a design oversight. Overall, the art and sound work in tandem to evoke a sense of childlike wonder, even if the visuals now appear dated.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Best Friends Ball received little critical attention, a fate common to licensed titles aimed at young audiences. Its legacy, however, is preserved through fan communities and archival efforts. Notably, it was banned in Greece in 2004 as part of a misguided crackdown on “illegal gambling” in electronic gaming, a baffling classification given its educational content and lack of wager mechanics. This absurdity has since become a piece of gaming trivia, underscoring the game’s obscurity.

Commercially, the title performed modestly, packaged as a “PC Play Pack” alongside a bonus Sparkleberry Swirl figure to boost appeal. Its impact on the My Little Pony franchise is minimal; subsequent games like Mane Merge (2022) and A Maretime Bay Adventure (2022) abandoned its minigame format for more structured adventures. Yet, within the niche of children’s edutainment, it holds a cult following. Fan wikis like the My Little Pony G3 Wiki meticulously document its errors and unused content, preserving its quirks for posterity. The game’s influence is subtle; its emphasis on creativity over competition foreshadowed trends in “cozy games,” while its “play-with” philosophy anticipated modern sandbox titles like Animal Crossing. However, its technical limitations—poor save support, sound dependency—prevent it from being a timeless classic. Instead, it remains a historical curiosity, a snapshot of a bygone era when licensed games prioritized brand loyalty over innovation.

Conclusion

My Little Pony: Best Friends Ball is a product of its time and ethos—a digital embodiment of the G3 pony world’s emphasis on sweetness, simplicity, and friendship. Its strengths lie in its charming art style, creative minigames, and commitment to accessibility, offering a wholesome experience for its intended audience. Yet, its flaws—from repetitive fetch quests to technical hiccups—reveal the compromises of developing for young children in an era of evolving technology. As a historical artifact, it is more fascinating than flawless, a testament to the challenges of adapting a beloved toy into interactive media. While it may not hold up against modern standards, its legacy endures in the hearts of nostalgic fans and the annals of gaming history. Ultimately, Best Friends Ball succeeds not as a groundbreaking game, but as a heartfelt tribute to childhood imagination—a digital friendship ball that, for all its imperfections, still radiates warmth and joy.