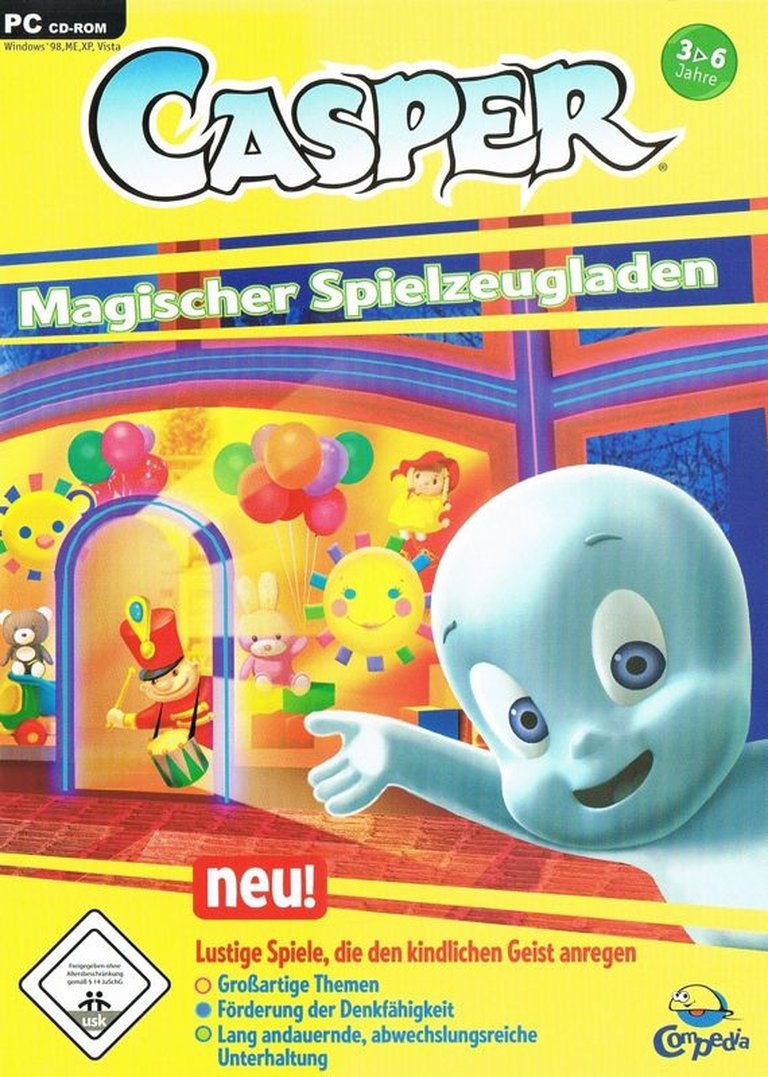

- Release Year: 2008

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Compedia Software & Hardware Ltd., Frogster Interactive Pictures AG

- Genre: Educational, logic, Math, Pre-school, toddler

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Coloring, Connect dots, Mini-games, Repair

- Setting: Magical Toy Store

Description

Casper: The Magical Toy Store is an educational game set in a whimsical toy store where Casper the Friendly Ghost assists a toy train in need by collecting batteries through a series of engaging mini-games. Designed for preschoolers aged 3-6, the game fosters logical thinking with activities such as coloring shapes, connecting dots, playing musical instruments, and solving puzzles, all enriched with playful cartoons and animations to create a fun learning environment.

Casper: The Magical Toy Store: A Ghostly Guide to Preschool Logic

Introduction: A Friendly Ghost in the aisles of Obscurity

In the sprawling and often contradictory historiography of video game adaptations, few franchises embody creative whiplash quite like Casper the Friendly Ghost. From the eerie, pre-rendered 3D of Interplay’s 1996 action-adventure titles to the point-and-click mysteries of the late 90s, the spectral everyman of Harvey Comics has been subjected to nearly every genre convention the industry has to offer. Nestled within this catalog, released over a decade after the 1995 film’s boom, is Casper: The Magical Toy Store—a 2008 Windows educational title from Compedia Software & Hardware Ltd. and Frogster Interactive Pictures AG. This is not a game of spectral scares or mansion exploration; it is a gentle, minigame-oriented logic tutor for children aged 3 to 6, framed within a simple narrative of kindness and problem-solving. This review posits that The Magical Toy Store represents a fascinating, if critically ignored, terminus point in the Casper license’s evolution: a deliberate shedding of the franchise’s darker Gothic trappings in favor of pure, unadulterated pedagogical utility. It is a game less concerned with ghostly lore and more with foundational cognitive skills, existing at the intersection of decades-old character recognition and the early-2000s boom in “edutainment” software. Its value lies not in revolutionary design, but in its serviceable, earnest execution within a crowded and often-derided market segment.

Development History & Context: The Compedia Model in a Waning Format

To understand Casper: The Magical Toy Store, one must first situate its developer, Compedia, within the European educational software landscape of the 2000s. Compedia, a Czech/German studio, specialized in license-based children’s titles, often adapting popular European TV shows and characters into CD-ROM-based minigame collections. Their output was characterized by modest budgets, tight development cycles, and a consistent template: a simple frame story linking a series of discrete, self-contained activities designed to teach colors, shapes, numbers, and basic logic.

The game’s release year is noted as both 2006 (on the Compedia Wiki) and 2008 (on MobyGames and My Abandonware). This discrepancy points to common practices in regional publishing. It was likely developed around 2006–2007, with the 2008 date reflecting its wider international or German-language release (the MobyGames entry lists multiple German/Czech/Slovak title variants). It arrived at a transitional moment for CD-ROM edutainment. The late 2000s saw the dominance of flash-based web games and the nascent rise of mobile app stores (the iPhone launched in 2007). The CD-ROM, once the king of household educational software, was becoming a legacy format. Casper: The Magical Toy Store thus feels like a final ember of a specific publishing model: a physical product sold in toy stores or software aisles, reliant on a known brand (Casper) to drive sales, with content designed for repeated, short-play sessions on a family desktop computer.

Technologically, the game reflects its era and budget. Source descriptions mention “cartoons and animations” but specify no advanced graphical techniques. Given Compedia’s track record and the 2D nature of the described minigames, the title almost certainly utilized pre-rendered 2D sprites and basic vector or frame-by-frame animation—a stark contrast to the 3D polygonal ghosts of the 1996 Interplay games. The constraint was not pushing graphical boundaries, but ensuring reliable performance on the minimum specified hardware: a Windows 98 machine with a Pentium processor and a mere 64MB of RAM. The goal was accessibility, not awe.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Batteries for Benevolence

The narrative of Casper: The Magical Toy Store is not a adaptation of any prior Casper film or cartoon plotline. Instead, it constructs a new, archetypal scenario perfectly suited to its preschool audience. The story, as detailed on the Compedia Wiki, is succinct: Casper visits a toy store and encounters a toy train, which is distressed because its lack of batteries prevents it from performing two acts of kindness: taking a sick doll to the doctor and transporting a band of animal toys to a concert. Casper, embodying his “friendly” ethos, immediately offers to find batteries for the train.

This plot is a masterclass in efficient, child-appropriate storytelling. It establishes:

1. A Problem: The train is helpless and sad due to a simple, physical lack (batteries).

2. A Moral Imperative: The train’s purpose is to help other toys (the sick doll, the band). The altruism is transitive and clear.

3. The Hero’s Role: Casper’s function is not to exorcise ghosts or save a haunted estate, but to be a problem-solver and a helper. His ghostly nature is irrelevant to the plot; he is simply the protagonist.

4. A Concrete Goal: Seven batteries are needed. This provides a clear, numerical objective for the child player, transforming the abstract “be helpful” into a tangible quest (“Let’s find 7 batteries!”).

Themes are correspondingly basic but foundational: kindness as active assistance, helping those in need, and the satisfaction of completing a task for others. There is no conflict with Carrigan Crittenden, no threat from the Ghostly Trio, no existential questions about life, death, or haunting. The antagonistic force is a simple resource shortage. The resolution is communal joy—the train can fulfill its duties, the doll gets care, the band plays. Casper receives no tangible reward beyond the train’s gratitude, reinforcing the idea of help as its own reward. This narrative purification strips the Casper franchise down to its most basic, marketable trait: the friendly ghost who wants to be your friend and do good deeds. It is a narrative engineered for maximum emotional safety and moral clarity.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Battery Economy

The entire gameplay of Casper: The Magical Toy Store is built upon a single, elegant meta-loop: The Battery Economy. The player must win minigames to earn batteries. Seven batteries are required to complete the core narrative arc and “finish” the game. This creates a structured progression system perfectly suited for short attention spans. Each battery is a discrete victory, providing a frequent dose of positive reinforcement.

The core activities, as meticulously documented on the Compedia Games Wiki, are seven distinct minigames. Each targets a specific subset of “logical thinking” for the 3–6 age range:

- Connect the Dots: A classic exercise in numerical sequence recognition and spatial pre-literacy. The child must click on dots in ascending numerical order to reveal a hidden Casper-themed picture. The challenge is procedural and the reward is a completed, familiar image.

- Musical Band: This targets auditory memory and pattern recognition. In “Repeat” mode, the child listens to a sequence of musical notes played by cartoon animals and must replicate it by clicking the animals in order. A free-play mode exists, but the game-mandated mode is the memory challenge, a foundational skill for rhythm and early math patterns.

- Worm Dreams: This is the most complex activity, a three-stage multi-modal logic puzzle.

- Stage 1 (Grid Selection): The child is shown a hint (e.g., “a red circle”) and must navigate a grid where one axis represents shapes and the other represents colors. This teaches categorical intersection—understanding that properties (shape and color) combine to define a specific item.

- Stage 2 (Picture Assembly): A scrambled picture must be reassembled by swapping pieces. This is a jigsaw puzzle, developing spatial reasoning and visual part-whole analysis.

- Stage 3 (Coloring): Using the worm’s own coloration as a guide, the child must color the now-unsrambled picture. This is color matching and fine motor control within a defined schema.

- Coloring: A more open-ended creative expression and color recognition activity. The “magic wand” that changes body parts introduces a basic understanding of modifying object properties, while the brush allows freeform coloring.

- Breakout: This is a cause-and-effect and timing game. The child moves a cloud to prevent a ghost (likely Casper) from falling and popping balloons. It’s a simplified paddle mechanic teaching predictive motor control and reaction timing.

- Xylophone: Primarily a sensory and musical exploration tool. Using a hammer to strike notes teaches cause-effect and introduces basic pitch relationships. It’s less a “game” and more an interactive toy, aligning with the title’s “toy store” theme.

- Shapes: A spatial puzzle where a missing geometric piece must be rotated and fitted into a silhouette. This directly teaches shape recognition, rotation, and spatial fitting.

Systems & UI: The interface is intentionally simple, with large, colorful buttons and minimal text, relying on iconography and animated demonstrations. There is no character progression stats, inventory beyond the battery count, or complex settings. The “Win a battery” state is the only feedback loop, narrated or shown visually. The design philosophy is “fail forward” or “try again”—there is no game-over state from failure in a minigame; the child simply retries until successful, ensuring the primary educational goal (completing the task) is always met. This is a key design choice for its age group: frustration avoidance is paramount. The post-game feature of unlocking old Casper cartoon clips (noted on the Wiki) is a classic reward structure, using the licensed IP to extend play value after the educational goals are met.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetic of Comfort

The Magical Toy Store does not build a world in the traditional sense of exploration-based games. Its “world” is a series of static, illustrated screens—one for each minigame—linked by a simple map or selection menu representing the toy store. The setting is implied through the frame narrative but not directly rendered as a navigable 3D or even 2D space. The “toy store” is an abstract concept, a container for the activities, not a place to be immersed in.

The visual direction is bright, saturated, and卡通ish (cartoon-like). Characters and objects are rendered with thick, friendly outlines and smooth animations. Casper himself is likely presented in his classic, simplified, friendly ghost form—white, round, with a small mouth and big eyes—consistent with his preschool-friendly image. The aesthetic priority is clarity and friendliness. Objects must be easily identifiable, buttons large enough for developing motor skills, and colors distinct. The “magic” in the title is reflected in whimsical particle effects (sparkles for correct answers, happy animations) rather than any eerie or supernatural atmosphere.

Sound design is equally functional and gentle. The description mentions “cartoons and animations” with sound, implying short, cheerful musical stings, positive reinforcement sounds for correct actions (dings, cheers), and simple, non-intrusive background music. Auditory cues are likely used in the Musical Band and Worm Dreams activities, reinforcing the learning objectives. The soundscape is one of encouragement, not tension. The overall atmosphere is one of safe, structured play—the antithesis of the haunting, echoing halls of Whipstaff Manor from the 1995 film.

Reception & Legacy: A Whisper in the Edutainment Aisle

Casper: The Magical Toy Store exists almost entirely outside the sphere of traditional game criticism. As noted on MobyGames, it has no critic reviews and, as of the last data pull, only 3 collectors in the MobyGames database. Its My Abandonware page holds a user score of 4.4/5 from 10 votes, with the description calling it “an above-average pre-school / toddler title in its time.” This is the sum total of its measurable reception: a faint, positive signal from a tiny community of preservationists and nostalgic adults.

Its commercial performance is unrecorded in standard industry databases. Given its publisher—Compedia, a niche educational specialist, and Frogster, a German publisher with a mixed portfolio—it was almost certainly a modest, regionally-focused release, likely selling adequately in Central European software sections without making a ripple internationally. It was not a flagship title; it was product line filler, a way to leverage the Casper name for another year on the back of a publishing catalog.

Its legacy is one of functional obscurity. It did not influence other games. It did not revive the Casper franchise (that honor would go to the 2006 Casper’s Scare School tie-in games). It represents a dead-end branch on the Casper game tree: the pure, unadulterated edutainment spinoff. Within the broader history of video games, its significance is as a data point:

* It demonstrates the late-stage commodification of a film license, repurposed for the lowest-common-denominator educational market.

* It exemplifies the “batteries” or “stars” collection mechanic as a universal reward system in preschool software.

* It stands in stark contrast to the more ambitious, genre-mixing attempts of the 1996–2002 Casper games, showing how a property could be sanded down to its most basic, inoffensive premise.

* It is a relic of the CD-ROM era’s final days in the educational sector, a format-dependent product that would become nearly obsolete within five years of its release.

The Wikipedia article on the broader “Casper” video game series does not mention The Magical Toy Store, a telling omission that underscores its separation from the “main” lineage of Casper games (which are all action-adventure or point-and-click titles). It exists in its own, minor canonical universe.

Conclusion: A Competent Ghost in the Machine

Casper: The Magical Toy Store is, by any measure of critical or cultural impact, a negligible artifact. It offers no technical marvels, no narrative depth, and no gameplay innovation that echoed beyond its own tiny genre. Judged by the standards of 2008’s burgeoning indie scene or today’s acclaimed “cozy games,” it is simplistic and transactional.

However, to dismiss it entirely is to miss its quiet, achieved purpose. Evaluated on the terms set by its own design—as a tool for 3-to-6-year-olds to practice logical thinking within a safe, friendly, and brand-recognizable context—it appears competent and sufficient. It provides seven distinct, well-defined activities targeting key developmental skills (sequence, pattern, color, shape, memory, spatial reasoning). Its feedback loops are immediate and positive. Its barrier to entry is minimal. It understands its audience’s cognitive and motor limits and designs accordingly. The battery-collection goal gives a child a clear, achievable reason to engage with each minigame.

Its ultimate verdict in video game history is that of a footnote, but a purposeful one. It is the endpoint of one logical path for a licensed character: from supernatural protagonist, to action hero, to puzzle-solver, and finally, to a purified vessel for educational exercises. Casper: The Magical Toy Store is the moment the Friendly Ghost finally and completely became a teacher’s aide, his haunting days forever behind him, replaced by the quiet magic of a correctly colored worm or a perfectly assembled puzzle. For the child who played it in 2008, it may have been a few hours of fun with a familiar face. For the historian, it is a clear, unpretentious snapshot of a very specific, very pragmatic moment in the long, strange marriage of intellectual property and early childhood education. It is not a game to be celebrated, but one to be acknowledged as a perfectly functional component of its time and market—a friendly ghost in the machine of pre-school software.