- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Buka Entertainment, Frogster Interactive Pictures AG

- Developer: G5 Software LLC, Orion

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Combat, Destruction, Exploration, Puzzle-solving, Vehicle control

- Setting: 1950s, Cold War, Moscow, Subway

- Average Score: 60/100

Description

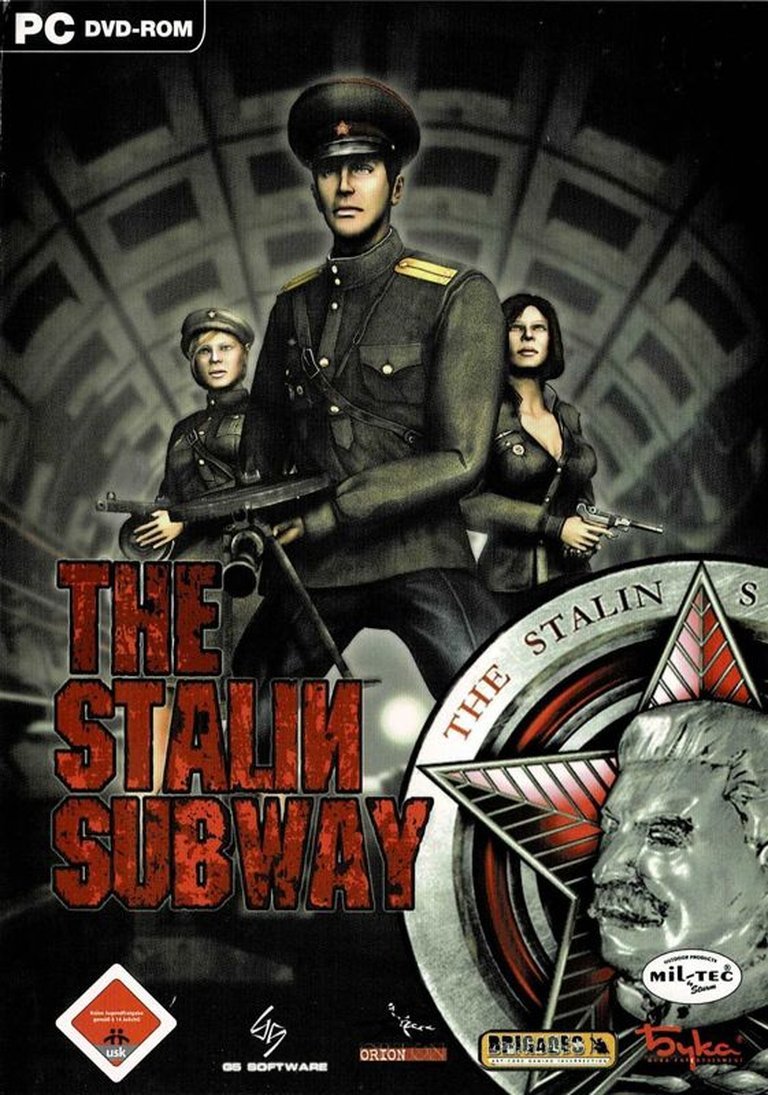

Set in the early 1950s Moscow during the Cold War, ‘The Stalin Subway’ is a first-person shooter where players assume the role of MGB lieutenant Gleb Suvorov. After uncovering a plot by high-ranking officials to assassinate Joseph Stalin with a stolen nuclear bomb, Suvorov must battle through the city’s extensive subway network and other subterranean installations, such as Kremlin dungeons and secret bunkers, to reach the bomb’s location and defuse it, saving Stalin and innocent civilians.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy The Stalin Subway

PC

The Stalin Subway Patches & Updates

The Stalin Subway Mods

The Stalin Subway Guides & Walkthroughs

The Stalin Subway Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (68/100): Pretty regular first player shooter, nothing groundbreaking

mobygames.com (53/100): A highly atmospheric and violent shooter – from Russia, without love.

oldpcgaming.net : It’s average on its best days, formulaic as hell on its worst.

The Stalin Subway Cheats & Codes

PC

Press ~ during gameplay to open the console and enter codes.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| godmode <0 or 1> | Toggle God mode |

| noclip <0 or 1> | Toggle no clipping mode |

The Stalin Subway: A Flawed Gem of Soviet-Era FPS Gaming

Introduction: The Red Star’s Dim Glow

In the mid-2000s, the first-person shooter genre was dominated by the polished, Hollywood-inspired blockbusters of the West: the sci-fi horror of Doom 3, the canine companionship of F.E.A.R., and the gritty realism of the burgeoning Call of Duty series. Into this landscape stepped a bizarre, defiantly regional challenger from the Russian software houses G5 Software and Orion Games: The Stalin Subway (Russian: Метро-2, “Metro-2”). Its premise was instantly provocative—a Cold War thriller where the player embodied not a GI Joe or a space marine, but a loyal officer of Stalin’s MGB, fighting to save the very dictator whose regime typified the genre’s traditional antagonists. This was not merely a change of scenery; it was a deliberate, almost rebellious, inversion of geopolitical narrative tropes. Yet, as this review will exhaustively argue, The Stalin Subway is a title defined by a profound and persistent dissonance. For every bold, atmospheric stroke, there is a corresponding flaw in execution; for every moment of intriguing, Grimdark immersion, ajar gameplay or technical stumble. It stands as a fascinating, deeply flawed artifact—a cult classic in the making that never quite escaped the confines of its own ambitious, compromised vision. The thesis is clear: The Stalin Subway is a game of potent contradictions, a technically adept but mechanically uneven and tonally unsettling experience that offers a crucial, if problematic, window into the aspirations and limitations of mid-2000s Eastern European game development.

Development History & Context: The “Orion” and the “G5”

The genesis of The Stalin Subway lies in the partnership between two distinct Russian development entities. Orion Games (often credited simply as “Orion”) functioned as the lead studio, bringing to bear its proprietary Orion Engine, a technology previously showcased in their 2003 title Hellforces. G5 Software acted as a co-developer, a common model in the region’s industry. The key creative figures identified in the credits are Nikolay Khudentsov (VP Development, Lead Programmer) and Alexey Pastushkov (Project Manager, Lead Designer, Level Designer), who appear to have been the project’s twin pillars. Their prior work includes Hellforces, a Western-front WW2 shooter where the player fought against communists, making the thematic pivot to a pro-Stalin narrative in The Stalin Subway a deliberate, almost cheeky, reversal.

The technological context is the Orion Engine, notable for its use of the PhysX physics middleware (a relatively new and buzzworthy technology at the time) and, crucially, its implementation of instantaneous quick-saving and loading. This last feature, praised in multiple reviews, was a significant quality-of-life advantage over many contemporaries, allowing for a fluid, uninterrupted pace of play that catered to the hardcore shooter demographic. However, the engine’s other capabilities were more mixed. While capable of impressive specific effects—like realistic water simulation and detailed glass fracturing—it struggled to compete with the graphical fidelity of 2005’s Western leaders like Half-Life 2 or F.E.A.R.. The game’s visual identity was also shaped by a commitment to photorealism through photography, with the art team using real-life images of Moscow to model environments, an approach that yielded authentic-looking locations but often at the cost of artistic cohesion and optimized performance.

The game was announced at E3 2005, where GameSpot highlighted its “combination of historical fiction plotline and modern FPS gameplay” as a key differentiator, expressing particular interest in its physics-based bullet penetration. This early buzz positioned it as an “alternate history” title with potential. Published in Russia by Buka Entertainment in September 2005, it saw a limited Western release in October 2005 through publishers like Frogster Interactive. Its launch coincided with a shooter market hungry for novelty but skeptical of Eastern European productions, which often carried reputations for technical jank and dated design philosophies.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Stalin’s Shadowy Conspiracy

The Stalin Subway presents a tightly wound, pulpy conspiracy thriller set against the oppressive backdrop of 1952 Moscow, in the final years of Stalin’s rule. The player assumes the role of MGB Lieutenant Gleb Suvorov, a newly promoted officer whose first day on a new assignment descends into chaos when he overhears a phone call in which KGB agents arrest his father, Professor Suvorov, a scientist involved in a secret nuclear weapons program codenamed “D-6”. This personal stake quickly expands into a geopolitical crisis: a cabal of high-ranking, ambition-crazed military officials, led by a renegade general, has stolen a tactical nuclear device. Their plan is to detonate it during a Party assembly, killing Stalin, the Politburo, and thousands of civilians, and framing the West to seize control.

Suavorov is joined by the enigmatic GRU officer Natalia Mihaleva, whose true allegiance remains murky throughout the original game (a mystery the sequel, Red Veil, only deepens without resolving). The narrative framework is a classic race-against-time structure, taking the player through a vertical slice of Stalinist Moscow’s architecture: the Moscow Metro (including the legendary secret “Metro-2” line), the KGB Lubyanka Building, the Kremlin, the Moscow State University, sprawling sewers, an abandoned mine shaft, and finally, Stalin’s secret bunker. This tour of iconic, subterranean locations is the game’s primary conceptual strength, offering a virtual “dark tourism” through the Cold War’s most notorious symbols.

Thematically, the game attempts to explore paranoia, duty, and ideological extremism. However, its execution is profoundly uneven. The plot is delivered via stilted in-engine cutscenes and sparse dialogue, with a voice cast (in the English localization) that famously includes the voice actor for the Bruce Willis stand-in from the Die Hard FPS games, creating a jarring, uncanny valley effect where a Soviet hero sounds like a B-movie American action star. This undermines narrative immersion entirely. The central irony—a game where you fight for Stalin—is presented with a curious lack of introspection. Gleb’s loyalty is never meaningfully questioned; the traitors are mere power-hungry militarists. The game misses a profound opportunity to critique Soviet authoritarianism from within, instead opting for a straightforward “save the leader” template that feels philosophically neutered.

A fascinating, if unintentional, thematic layer emerges from the game’s “Hostage Spirit-Link” mechanic (as catalogued by TV Tropes). The HUD features two squares above the health bar that turn red if the player kills a civilian. Killing three civilians in a level results in an instant game over. This system intends to enforce a “Would Not Shoot a Civilian” ethos, but its implementation is bleakly absurd. As one critic noted, you can blow an enemy soldier’s brains onto a wall, only for a blankly staring female officer in the same room to remain utterly unperturbed, her eyes rolling mindlessly. This creates a deeply nihilistic and cold-blooded atmosphere. The violence is graphic, clinical, and devoid of emotional consequence, mirroring the dehumanizing regime the player serves. The game doesn’t condemn this violence; it merely simulates it with detached, procedural efficiency. The bizarre, puppet-like behavior of ambient NPCs—standing around, blinking, half-smiling—contributes to a uniquely disturbing, surreal Soviet kafkaesque mood that is The Stalin Subway‘s most indelible and unsettling achievement.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Grind of the Metro

At its core, The Stalin Subway is a classic, late-90s/early-2000s style corridor shooter filtered through the specific lens of Russian FPS design traditions (akin to Hellforces and Iron Storm). Its fundamental loop is: traverse a large, multi-path level, locate keys/power supplies to progress, fight waves of identically-modeled enemy soldiers, and reach the objective marker.

Level Design & Progression: The most consistent criticism across reviews is the repetitive and often confusing level architecture. While not strictly linear—you can frequently choose between several corridors—the alternative paths often loop back or lead to dead ends, making exploration feel unrewarding. A notorious example cited is the sequence requiring the player to disembark from a train, fight across a platform, board another train, and repeat this process for three stations in a row. Objectives are frequently vague (“find the key to the restricted area”) or require finding obscure secret passages (ladders, hidden stairwells), leading to frustrating backtracking. This design philosophy, common in Russian shooters of the era, prioritizes a sense of monumental, labyrinthine scale over intuitive flow and can feel arbitrarily punishing to Western audiences accustomed to more guided level design.

Combat & Arsenal: The gunplay isfunctional but unspectacular. The arsenal is a highlight, featuring a satisfying array of period-accurate Soviet and captured Axis weapons: Makarov pistol, PPSh-41, AK-47, PPS-42, STEN gun, Luger, and the standout, rare inclusion of the PTRS-41 anti-tank rifle—a weapon of immense stopping power that feels deliberately overpowered. Weapon handling includes authentic visual details (like the AK-47’s muzzle climb) and a variety of grenades (frag, RKG-3, Molotov) and even a flamethrower. However, enemy AI is a major weak point. Critics consistently describe it as simplistic: enemies often stand still, take poor cover, and exhibit minimal tactical awareness. While the player review notes that on Hard difficulty, certain encounters (like the construction site sniper sequence) provide a genuine, tense challenge requiring use of cover and movement, this seems the exception. The AI’s inconsistency—sometimes dumb, sometimes sharply accurate—points to uneven scripting.

Destructibility & Interaction: The game heavily promotes its destructible environment (over 300 types, according to Steam store info). Crates, glass, sinks, chairs, and ash trays can be shattered. While visually satisfying, this feature is almost entirely pointless in terms of gameplay, as the player review astutely notes. It serves as atmospheric set-dressing rather than a meaningful mechanic. Similarly, searching drawers and cabinets for ammo/health is a light but appreciated touch that encourages cautious exploration.

Technical Systems: The Orion Engine’s instantaneous save/load is universally praised as a strong point, maintaining momentum. Conversely, the configuration and setup process is criticized as archaic. There is no auto-detect; instead, a benchmark utility flies through the construction site level, reporting min/max/avg FPS, forcing the player to manually tweak settings for optimal performance—a frustrating barrier to entry. More severely, a critical bug plagued many users: the music track would cause the game to crash to desktop at every checkpoint, as experienced by the primary user reviewer. Disabling the music was a necessary fix, highlighting a serious lack of polish. The German version famously censored almost all blood and gore, with enemies vanishing instantly upon death, a regional quirk that fundamentally altered the game’s visceral tone.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Oppressive Gaze

Where The Stalin Subway most successfully carves its identity is in its atmosphere of crushing, depressive Soviet realism. The environment art, while technically dated by Western standards, achieves a powerful sense of place through its commitment to authentic Moscow locations. The attention to detail in the Lubyanka offices, the grim concrete of the Metro stations, the cold stone of the Kremlin dungeons, and the claustrophobic sewers creates a palpable sense of being trapped within a vast, monolithic state machinery.

The visual presentation is a study in contrasts. Certain effects are exceptionally well-realized for its budget: the realistic water ripple and flow in puddles and sewage, the convincing shattering and dangling fragments of glass, the meticulous detail on weapon models. These flashes of technical competence are undermined by the overall muddy color palette (dominated by grays, browns, and sickly greens) and, most famously, the character models. As repeatedly observed, human characters—both allies and enemies—look like “synthetic emotionless marionettes.” Their animations are stiff, their facial expressions non-existent or bizarre (the rolling eyes, the fixed half-smiles). This isn’t necessarily poor animation; it feels like a deliberate, if clumsily executed, aesthetic choice to render the populace as hollowed-out cogs in the machine. It’s unsettling and perfectly in tune with the game’s nihilistic tone, even if it wasn’t fully intended.

The sound design is solid and functional. Gunfire is loud, weighty, and authentic for the era. Environmental audio—hissing gas leaks in sewers, the hum of generators, the slosh of water—is adequately deployed to reinforce the abandoned, industrial settings. The music, however, is a point of contention. The user reviewer admits to liking it, but its propensity to cause crashes rendered it a liability. Its absence in a stable playthrough leaves the game even more atmospherically barren, relying solely on diegetic sound.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Classic in the Making?

Upon release, The Stalin Subway received generally mixed to negative reviews from Western critics, aggregating to a 50% score on MobyGames. Common complaints crystallized around: poor and simplistic AI, repetitive and confusing level design, a lack of innovation in core FPS mechanics, and technical instability. German magazine PC Games gave it 68%, praising the premise but noting AI flaws. GameStar (48%) and 4Players (35%) were scathing, dismissing it as a non-essential, low-quality effort in a market saturated with superior shooters. The Russian press was slightly more forgiving but still lukewarm (e.g., Absolute Games 55%, IGROMANIA 40%).

Commercially, it remained a niche, budget-title product. Its legacy, however, is more intriguing. It has developed a small but dedicated cult following, evident in its “Cult Classic” tag on Steam and its persistent 60% positive rating from over 666 user reviews there, a significantly more favorable assessment than the critic average. This disconnect suggests the game resonates with a specific audience: players intrigued by its unique historical setting, its unapologetic Soviet aesthetic, and its raw, unpolished charm.

Its most significant legacy is pioneering the “Moscow Metro” as a game setting. Released before You Are Empty (2006) and the landmark Metro 2033 (2010), The Stalin Subway was one of the first games to extensively feature the real and mythical subterranean networks of Moscow. It laid a thematic and spatial groundwork—the dark, claustrophobic, politically charged underground—that the Metro series would later refine into a globally recognized franchise. Furthermore, as a Russian-developed FPS with a politically provocative premise, it represents an early, if clumsy, attempt to export a uniquely post-Soviet gaming perspective, challenging the Cold War narratives长期 dominated by Western studios.

The 2008 sequel, The Stalin Subway: Red Veil (or Metro-2: Death of the Voord), shifted focus to Gleb’s wife, Lena, during the same crisis. It was notoriously panned, with Eurogamer Germany giving it a disastrous 1/10, suggesting the first game’s strengths were not transferable.

Conclusion: Verdict on a Subterranean Oddity

The Stalin Subway cannot be recommended as a great game by any conventional, critical metric. Its AI is often moronic, its level design can be frustratingly obtuse, its narrative is delivered with all the gravitas of a propaganda reel, and its technical presentation is riddled with bugs and dated visuals. To dismiss it entirely, however, would be to ignore its potent, singular qualities.

It is a fascinating period piece, a time capsule of mid-2000s Russian game development ambitions and limitations. Its greatest triumph is its uncompromising atmosphere—a suffocating blend of historical detail, surreal NPC behavior, and nihilistic violence that creates a uniquely disturbing vision of Stalinist Moscow. The inclusion of rarely-seen weapons like the PTRS-41 and the commitment to real-world locations demonstrate a creative spark often absent in cookie-cutter shooters. The instantaneous save system shows an understanding of player convenience that some larger studios lacked.

Ultimately, The Stalin Subway earns its place in video game history not as a masterpiece, but as a compelling, flawed artifact. It is a game that is perpetually at war with itself: its bold premise undermined by poor execution, its atmosphere elevated by technical mediocrity, its cultural specificity both its greatest strength and barrier to wider appeal. For historians, it is an essential study in regional game development. For players, it is a curious, budget-priced curiosity best enjoyed with lowered expectations and a keen interest in the Cold War’s dark, subterranean corners. It is a game that is, in the truest sense, of its place and time—a flawed gem mined from the shadowy tunnels of post-Soviet game design, forever echoing with the ghosts of its own ambitions.