- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: ASCARON Entertainment GmbH

- Developer: ASCARON Entertainment GmbH

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Hotseat, LAN, Single-player

- Gameplay: Art authentication, Auctions, Gambling, Plantation management, Sabotage, Trading

- Setting: art, Historical, Trade

Description

Set in 1918, Vermeer: Die Kunst zu erben is a turn-based strategy game where players assume the role of one of four nephews tasked by their wealthy uncle, Walther von Grünschild, to recover his stolen art collection. By managing plantations in the Third World, participating in auctions, gambling at horse races, and employing tactics like hiring middlemen or robbers, players must strategically plan daily actions to accumulate wealth and art expertise, ultimately aiming to become the heir.

Vermeer: Die Kunst zu erben Patches & Updates

Vermeer: Die Kunst zu erben: The Cult Classic That Masterminded the Art of Economic Strategy

Introduction: A Charming Anachronism in a Genre of Giants

In the sprawling library of 1990s PC gaming, where bloated simulations promised ever-greater complexity, Vermeer: Die Kunst zu erben (1997) stands as a deliberate and charming anachronism. It is not a game of thunderous spectacle or cinematic storytelling, but one of quiet, calculated moves across a globe-spanning board of colonial trade and high-stakes auctions. As a remake of the 1987 Commodore 64 original, it arrived with a clear lineage yet a distinct identity, embodying a specific German design philosophy that prized deep, interconnected systems over flashy presentation. My thesis is this: Vermeer: Die Kunst zu erben is a profoundly influential cult classic, a masterclass in elegant systemic design that forged a unique niche at the intersection of economic simulation, turn-based strategy, and thematic narrative. Its legacy is not measured in sales charts but in the dedicated minds it captivated with its intricate dance of commodity markets and canvas forgeries, offering a cerebral alternative to the era’s dominant Sim titles and football managers.

Development History & Context: The Ascaron Touch and the Tenacity of a Vision

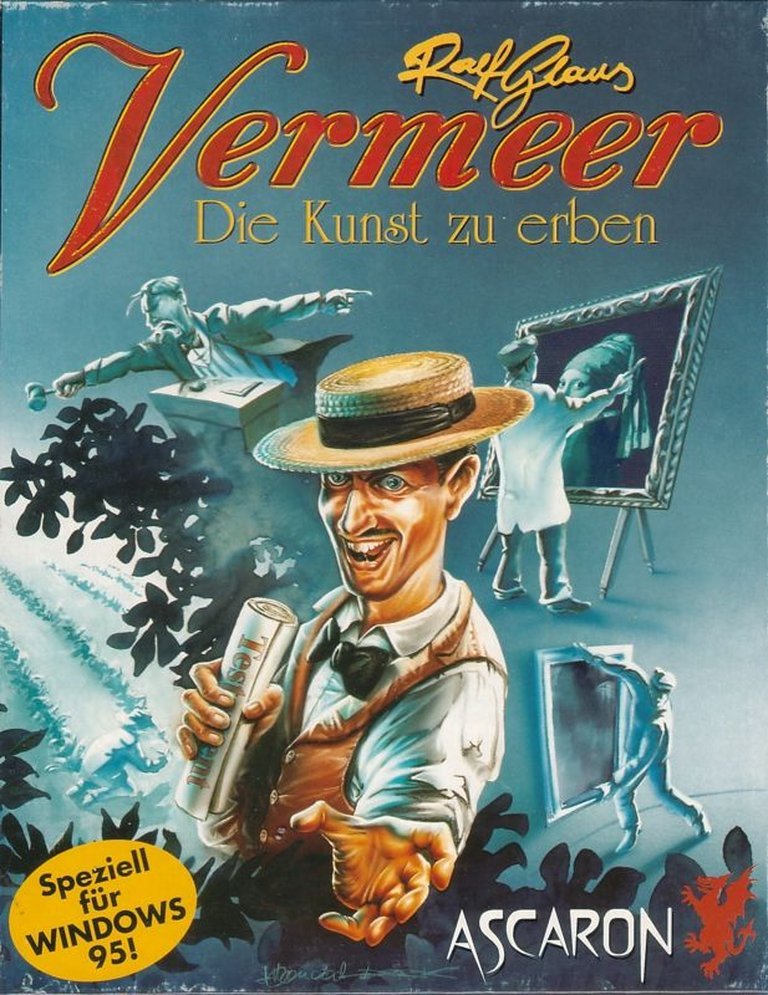

The game springs from the mind of Ralf Glau, the creator of the original 1987 Vermeer, and was brought to the Windows 95 era by ASCARON Entertainment GmbH, a studio that would become synonymous with deep, often niche, German management and strategy simulations (later known for the Anstoss football series and Patrician). The 1997 release is a “Windows 95 remake” in the purest sense: it retains the core game design buttranslates it into the contemporary SVGA (Super Video Graphics Array) resolution and color depth, a significant leap from the EGA and C64 predecessors. This was not a ground-up reinvention but a careful, loving restoration and modernization.

The technological constraints of the era are palpable. The game runs in a fixed, isometric, diagonal-down “first-person” perspective (a UI-centric view where you click on global locations), with hand-drawn 2D illustrations for characters and paintings. There is no 3D acceleration; its world is built from static maps, menu screens, and simple animations. Yet, within these constraints, Ascaron demonstrated considerable craft. The development team—a core of programmers (Moving Bytes), artists from Animagic, and designers—focused on clarity and functional beauty. The UI, as noted in the PC Player review, is “wonderfully clear” (wunderbar übersichtlichen), a critical achievement for a game dense with global logistics and auction tactics.

This game emerged into a 1997 landscape dominated by the likes of Theme Hospital and SimCity 2000—titles celebrated for their vibrant, humorous simulations. Vermeer presented a stark, almost austere contrast. It was a serious, historically-set economic strategy game for an audience that cherished the tense, spreadsheet-like depth of older titles like Hanse or Der Patrizier, as PC Games astutely observed. Its decision to be “networkfähig” (LAN/Hot Seat multiplayer) was a forward-looking feature that elevated it from a solitary puzzle to a fiercely competitive social experience, a rare and valued trait for the genre in Germany at the time.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Inheritance of a Lost Collection

The narrative framework is elegantly simple yet deeply motivating. Walther von Grünschild, a wealthy Berlin merchant and art patron, sees his priceless collection looted amid the chaos of post-World War I Europe (the game starting in 1918). On his deathbed, he devises a final testament: he sends his four nephews—the players—out into the world to recover the 40 missing paintings. The nephew who amasses the most valuable genuine collection will inherit his entire fortune and corporate empire. This premise does more than set a goal; it embeds every logistical and financial decision with personal and historical weight.

The themes are intricately woven with gameplay:

* Legacy vs. Commerce: The core tension is between the noble pursuit of reclaiming cultural heritage (the art) and the grubby, necessary means of generating wealth (colonial plantations). You are not an art historian; you are a ruthless capitalist art dealer.

* The Fog of Art History: The pervasive threat of Vico Vermeer forgeries introduces a constant layer of uncertainty and risk assessment. The fictional forger’s name is a direct, playful nod to the real Dutch Master, Jan Vermeer, grounding the game’s fiction in a recognizable art historical milieu. Distinguishing real from fake is not a mini-game but a strategic investment (visiting art schools) that pays dividends at auction.

* Anonymity and Subterfuge: The narrative touch of hiring a middleman (Makler) to bid anonymously is brilliant. It mechanically represents the clandestine nature of high-stakes art trading and creates a meta-game of bluffing and deduction among human players. Similarly, hiring robbers in Chicago to steal from rivals injects a direct, ruthless narrative of sabotage into the economic simulation, echoing the shady underbelly of early 20th-century trade.

* The Tyranny of Time: The game ends abruptly with the uncle’s death. As PC Joker lamented, this often occurs precisely when the player’s empire is most fascinating, creating a poignant, built-in narrative arc of ambition cut short. It’s a brutal, systemic storytelling device.

The “story” is delivered through sparse text, auction events, and the occasional portrait, making the player’s strategic choices the primary narrative engine. Your morning in Berlin deciding to send a ship from your Colombian coffee plantation, followed by an afternoon at a London auction where you outbid a rival for a questionable landscape, is the story of your Nephew’s bid for inheritance.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Grand Interlocking Machine

Vermeer’s genius lies in the relentless, cyclical interplay of its systems. The core loop is a multi-layered planning exercise across a global stage.

1. The Turn-Based Global Grid: One round equals one day. A player’s turn involves a sequence of actions: traveling (which consumes days), managing plantations, shipping goods, and attending auctions. The ability to set the round timer from 5 seconds to infinite is a masterstroke of accessibility, allowing for either frantic real-time planning or meticulous, paused strategizing.

2. The Plantation Engine: You can establish up to 24 plantations in the “Third World” (South America, Africa, Asia) producing coffee, cacao, tea, or tobacco. This is your primary revenue stream. However, every action—planting, harvesting, loading onto ships, unloading at warehouses—requires your physical presence. This forces profound logistical planning. You cannot passively watch money roll in; you must be the traveling manager, deciding which region needs your attention most urgently.

3. The Global Market: Goods are sold at warehouses in London and New York to pre