- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Empire Interactive Europe Ltd.

- Genre: Compilation

Description

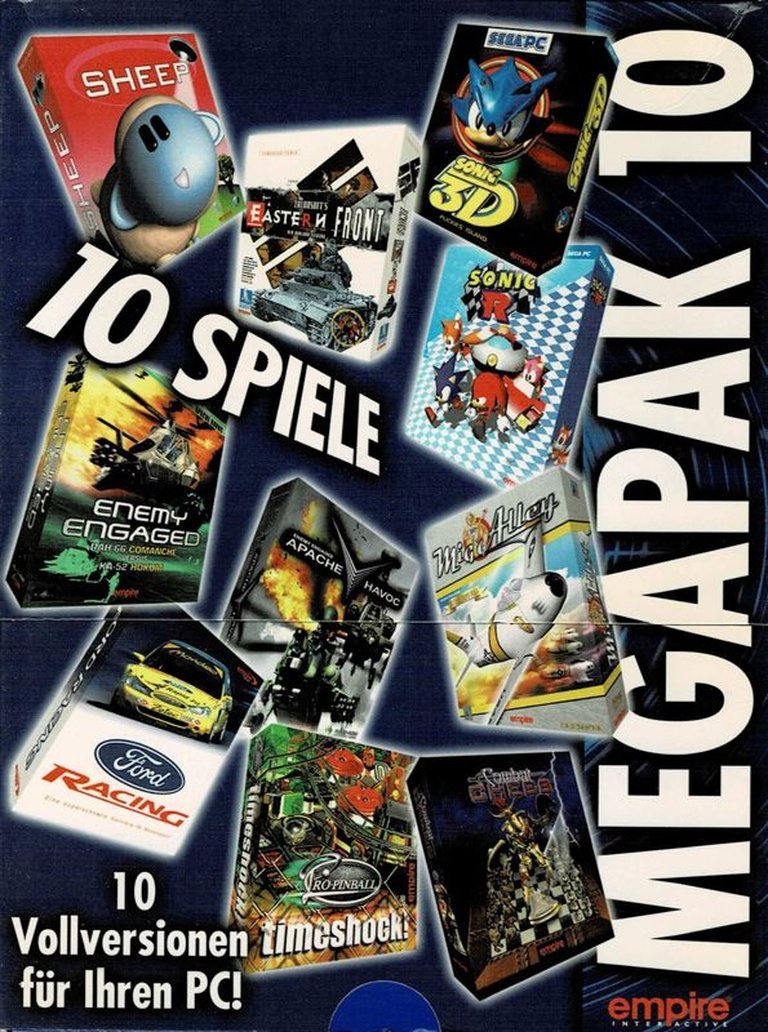

Megapak 10 is a compilation video game released on December 4, 2001, for Windows, featuring a diverse collection of ten titles including combat simulations like Enemy Engaged, racing games such as Ford Racing, classic Sonic the Hedgehog games (Sonic 3D Blast and Sonic R), and strategy titles like TalonSoft’s East Front. As the tenth entry in the Megapak series by Empire Interactive, it bundles varied gaming experiences into a single commercial package.

Megapak 10: A Time Capsule of Pre-Steam Era Gaming Commerce

1. Introduction: The Ghost in the Bargain Bin

To understand Megapak 10, one must first understand the tactile, olfactory, and financial reality of mid-to-late 1990s PC gaming. It was an era of towering CRT monitors, the deafening click of CD-ROM drives, and the sacred ritual of installing from a stack of discs held together by a single, sinisterly thick manual. In this landscape, the “budget compilation” was a siren song for the cash-strapped enthusiast—a promise of endless variety for a fraction of the price of a single new release. Megapak 10, released by Empire Interactive Europe on December 4, 2001, for Windows, stands not as a game but as a meticulously packaged artifact of that dying epoch. It is the final, faint echo of a business model that thrived on randomness, perceived value, and the hope that within a box of ten disparate titles, one might find a hidden gem. This review argues that Megapak 10 is historically significant precisely because it represents the commercial and cultural nadir of the physical “big box” compilation. It is a document of transition: released just as digital distribution loomed, it bundles games from the late 1990s—a period of explosive genre experimentation—into a product that feels instantly anachronistic, a curated museum of recent past now presented as clearance-sale filler.

2. Development History & Context: The Anatomy of a Random Bundle

The Megapak series, originating with the confusingly numbered Megapak 11 in 1994, was the brainchild of Megamedia Corporation (later associated with Empire Interactive’s Xplosiv label). Its evolution mirrors the PC market’s shift from niche hobbyist pastime to mass-market entertainment. Early entries like Megapak 11 felt like multimedia sampler platters, mixing early CD-ROM experiments with aging DOS titles. By Megapak 6 (circa 1996) and Megapak 8 (1997), the formula solidified: select a handful of notable, often recent, titles from a publisher’s back catalog and one or two newer acquisitions, then bundle them with scant regard for thematic cohesion. Megapak 10, the purported final entry, exemplifies this late-stage iteration. Published by Empire Interactive Europe—a company known for its budget Xplosiv range—the compilation is a “greatest hits” of Empire’s own stable and licensed titles circa 1997-2000.

The technological context is one ofbridging generations. The included games (Sonic 3D Blast, Sonic R, Ford Racing, Pro Pinball: Timeshock!) are products of the Windows 95/DirectX 5-6 era, designed for 15-inch monitors and 66MHz CPUs. Their presence in late 2001, on the cusp of the GeForce 3 and the dominance of Grand Theft Auto III and Halo, creates a jarring temporal dissonance. The “vision” wasn’t artistic but mercantile: move aging inventory by associating it with the prestige of a numbered series and the allure of “10 GAMES!” in giant font on the box. The gaming landscape of 2001, as seen in the Wikipedia entry for that year, was defined by seismic shifts—the launch of the Xbox and GameCube, the rise of the MMO with Final Fantasy XI, and the release of narrative and mechanical titans like Final Fantasy X and Grand Theft Auto III. Megapak 10 existed in the shadow of these giants, a budget relic aimed at a different demographic: the parent buying a “computer game” for a child, or the frugal student with a Pentium II.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Story of Value Itself

Megapak 10 possesses no canonical narrative, characters, or dialogue. Its “story” is the consumer’s experience, a meta-narrative of anticipation, discovery, and often, disappointment. The implied themes are:

* The Promise of Abundance: The box art and title scream quantity. The thesis is that ten games provide ten times the value, ignoring the qualitative chasm between a Sonic R and a Mig Alley.

* Curated Chaos: The selection is a deliberate, if nonsensical, cross-section of late-90s PC genres. It includes:

* Arcade Racing: Ford Racing (1999), Sonic R (1997).

* Flight/Combat Sim: Enemy Engaged: Apache/Havoc (1998), Enemy Engaged: RAH-66 Comanche versus Ka-52 Hokum (2000), Mig Alley (1999).

* Strategy/Simulation: TalonSoft’s East Front (1997), Sheep (2000), Combat Chess (1997).

* Action/Platformer: Sonic 3D Blast (1996).

* Pinball: Pro Pinball: Timeshock! (1997).

The thematic link is purely commercial: these are games Empire Interactive or its partners could license cheaply. There is no through-line like the pilgrimage of Final Fantasy X; the only journey is the user’s cursor navigating the install menu.

* The Nostalgia Engine (Unintentional): For a historian, the compilation is a primary source. The presence of Sonic R (a Saturn/PC port of a Sonic console racer) and Sonic 3D Blast (an isometric Sonic platformer) are fossils from Sega’s post-Mega Drive, pre-Dreamcast wilderness years. Combat Chess and East Front speak to the brief, hardcore popularity of historical strategy wargames on PC. Sheep, a bizarre “herding simulation,” is a perfect example of the experimental, almost avant-garde oddities that flourished in the late 90s. The narrative is one of a specific moment in gaming history when genres were being stress-tested, and publishers sought every avenue to monetize software, even by clashing aesthetics together.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Study in Jarring Juxtaposition

Analyzing Megapak 10‘s mechanics requires analyzing ten distinct systems, a task that highlights the compilation’s fundamental flaw: it offers no unified experience. The systems range from:

* Arcade-Racing: Ford Racing and Sonic R employ simplistic handling, track designs focused on spectacle over simulation, and a “pick-up-and-play” ethos. Power-ups and theme tracks (Sonic zones) define them.

* Hardcore Sims: The Enemy Engaged series boasts deeply complex radar systems, avionics modeling, and damage assessment. East Front is a operational-level hex-based wargame with supply lines and unit morale. These are not games but simulations, requiring manuals and patience.

* Action/Platforming: Sonic 3D Blast uses isometric jumping and pinball-like bumpers, a control scheme notoriously tricky on keyboard.

* Experimental Gameplay: Sheep is a puzzle/simulation hybrid where players guide sheep through obstacle courses using limited tools. Pro Pinball is a notoriously difficult, rules-heavy digital recreation of a physical table.

* Abstract Strategy: Combat Chess is standard chess with 3D pieces and animated captures.

The “innovative” system is the compilation’s very existence: the user must become a curator, a systems manager installing and configuring software from disparate eras on a single modern (for 2001) OS. This often involves wrestling with DOSBox for the oldest titles, compatibility patches, and manual configuration files. The flawed system is the lack of any central launcher, unified settings, or even consistent install procedures. It’s a passive collection, not an integrated product. The user’s progression is not measured in character levels but in which icons actually launch without a crash.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: A Collage of Inconsistent Visions

Megapak 10 has no single world. It presents ten:

1. The Corporate Fantasy of Ford Racing: Bland, logo-heavy environments representing Ford’s global marketing vision.

2. The Sega Arcade of Sonic R: Bright, polygonal, and chaotic tracks lifted directly from the Sonic universe, with a low-poly count that was dated even in 1997.

3. The Clinical Cockpit of Enemy Engaged: Green-on-black radar screens, detailed instrument panels, and the stark, terrifying beauty of a HUD in a combat simulator.

4. The Tactical Map of East Front: A gridded, beige-and-brown representation of the Eastern Front in 1941-45, where hexagons represent battalions.

5. The Pastoral Puzzle of Sheep: Bright, colorful, and consciously cute landscapes designed to contrast with the chaotic herding mechanics.

6. The Neo-Noir of Pro Pinball: Timeshock!: A moody, photorealistic (for 1997) pinball table with cosmic horror themes.

The visual direction is nonexistent as a whole. The art styles clash violently from the anime-inspired Sonic games to the grim, realistic unit sprites of East Front. The sound design is equally fragmented: chiptune-esque Sega music, the ominous engine drones of attack helicopters, the clatter of pinball bumpers, and the somber orchestral stabs of Combat Chess‘s score.

These elements do not contribute to an overall experience; they define the boundaries of each contained micro-experience. The only atmosphere that permeates the whole is one of temporal disconnect. You are not playing a cohesive vision of 2001; you are operating a museum exhibit where the labels are wrong, and the artifacts from 1996, 1998, and 2000 are crammed together. The “feel” is of a hard drive being populated with ghost software.

6. Reception & Legacy: The Sound of One Hand Clapping

Critical Reception at Launch: There was none. Megapak 10 was not reviewed by mainstream outlets. It existed outside the critical discourse, which in 2001 was focused on canonical releases like Final Fantasy X (a 39/40 in Famitsu), Grand Theft Auto III, and Halo. It was catalog fodder, advertised in the back of magazines or on bargain shelves. Its reception was purely transactional and private—a silent purchase for a quiet evening of potential disappointment.

Commercial Performance: Its sales figures are lost to history, dwarfed by the 2+ million first-day sales of Final Fantasy X in Japan. It was a low-margin, high-volume product for Empire Interactive, a way to monetize a catalog. Its success was measured in how many dusty boxes could be moved from aCompUSA or software discount bin.

Evolution of Reputation: The reputation of Megapak 10 is intrinsically linked to the demise of its format. As the “Inside The Big Cardboard Box” article eloquently details, compilations like this were a European phenomenon more than an American one. They were the PC equivalent of the “2-for-£15” bin, but with less choice. Their legacy is one of failed promise. The dream was discovery; the reality was installation followed by immediate return to Counter-Strike or Diablo II. The article’s author recalls, “In reality, this fun was often short-lived… fiddling around with them for half an hour or so before resolving to return to them at a later date (which I often did not do).” Megapak 10 is the archetype of this experience: a collection where the perceived value inversely correlated with the likelihood of deep engagement.

Influence on the Industry: Its influence is negative and defining: it demonstrated the limits of the physical compilation model. It proved that bundling wildly disparate games did not create synergy; it created a headache. The model was utterly annihilated by the rise of digital storefronts (Steam, 2003; GOG, 2008) and services like Xbox Live Arcade and PlayStation Store (2004-2005). These offered curated, downloadable, compatible, and often high-quality classic and indie games. The randomness and friction of Megapak 10 could not compete with the instant, reliable access of a $5 digital download of Pro Pinball. It is the last gasp of an era where getting a game meant acquiring a physical object, with all its attendant costs, complications, and surprises—good and bad.

7. Conclusion: A Valuable Curiosity, a Flawed Product

Megapak 10 cannot be judged as a “game.” It is a retail container, a historical specimen, and a cautionary tale. As a product, it is almost entirely flawed: it lacks cohesion, requires excessive user effort to function on modern systems, and contains games of wildly uneven quality and genre. The likelihood of any single player finding more than one or two titles of genuine interest is minimal. Its “value proposition” is mathematically dubious.

However, as a historical artifact, it is invaluable. It captures a specific moment when the PC gaming market was so vast and fragmented that publishers believed they could sell a strategy sim next to a Sonic racer and a flight sim to the same customer. It is a snapshot of the late-90s/early-00s development boom—the era that birthed the experimental titles like Sheep and the hardcore niches like East Front. It represents the final commercial breath of the physical compilation before the internet rendered it obsolete.

Its place in video game history is that of the canary in the coal mine for bundled software. It shows the endpoint of a path: selling volume over curation, physical over digital, hope over quality. In the same year, Final Fantasy X was pushing the narrative and technical boundaries of the RPG on a single, focused Blu-ray disc. Megapak 10 was pushing the boundaries of how many disparate, outdated .EXE files could be crammed onto ten CDs and still be called a “product.” It failed, and its failure paved the way for the curated, accessible, and respected re-release markets we have today. It is not a game to be played, but a lesson to be learned: in the digital age, curation is value. Randomness is just noise.