- Release Year: 1983

- Platforms: Atari 2600, Windows, Xbox 360

- Publisher: Activision, Inc., Microsoft Corporation

- Developer: Activision, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Character Switching, Material gathering, Patching holes

- Setting: Fairy tale

Description

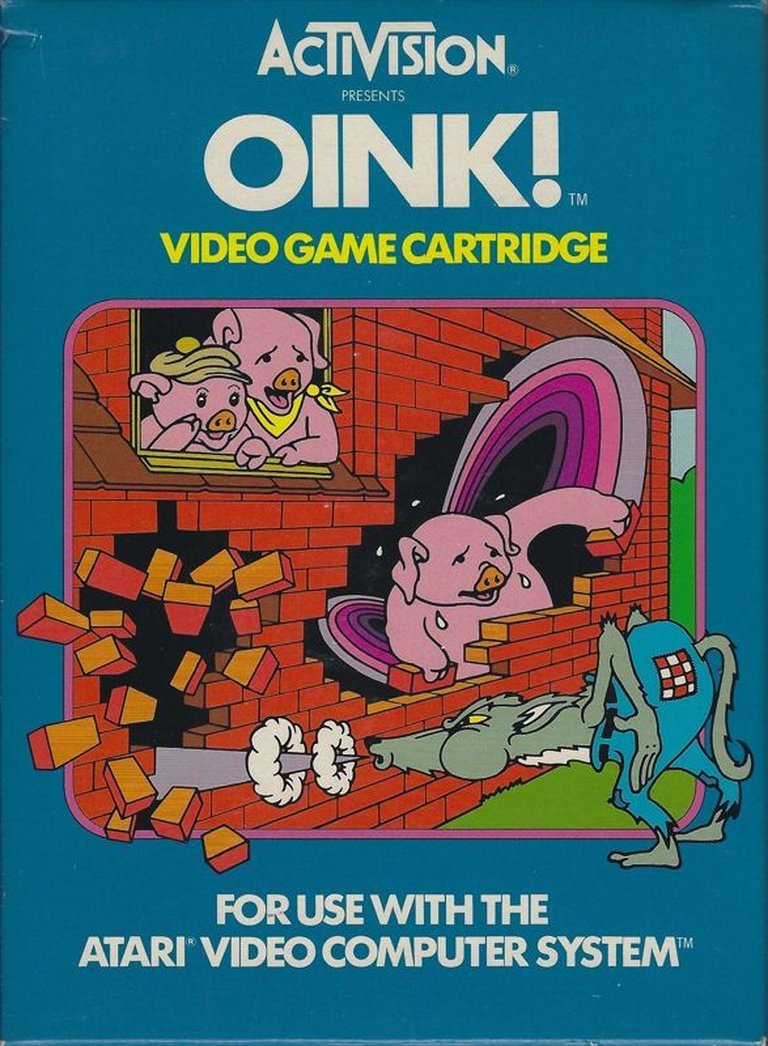

Oink! is an action game for the Atari 2600 based on the three little pigs fairy tale, where players sequentially control each pig to quickly patch holes in their houses—constructed from straw, sticks, and bricks—as the big bad wolf blows them down from below. The game intensifies with increasing difficulty, testing players’ stamina and reflexes in a competitive or cooperative 1-2 player arcade experience.

Gameplay Videos

Oink! Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com : Surprisingly, an ACTIVISION property that is actually underrated. Not A material but a B isn’t bad.

mybrainongames.com : It was visually quite good but the way the gameplay was executed seemed to favor the wolf.

Oink!: Review

Introduction: A Fairy Tale Forged in Silicon

In the annals of Atari 2600 history, where platformers and shooters dominated the cartridge landscape, Oink! stands as a puckish, defiantly odd duck. Released by Activision in April 1983, this game transforms the universally familiar fable of the Three Little Pigs into a tense, real-time test of reflexes and resolve. Designed by the prolific Mike Lorenzen, Oink! eschews the fantasy escapism of its contemporaries for a absurdly grounded, almost Sisyphean task: you are not the wolf, but the pig, frantically patching holes in your own home as a singular, relentless adversary attacks. This review posits that Oink! is a fascinating, if deeply flawed, artifact of the early 1980s—a game whose clever thematic adaptation and tense two-player dynamics are often hamstrung by repetitive, stamina-testing gameplay, yet whose unique vision secures its place as a cult curiosity in the Atari pantheon.

Development History & Context: The Last Gasp of a Changing Era

The Studio and the Creator: Oink! emerged from Activision’s golden era, a period defined by the studio’s reputation for quality and design innovation after its split from Atari. Mike Lorenzen, the game’s sole designer and programmer, was a veteran of the scene, having previously worked on titles like Frostbite and Plaque Attack. His bio on MobyGames credits him with over ten games, situating him firmly within the “second wave” of Activision developers who pushed the hardware’s limits with creative concepts rather than pure technical spectacle.

Technological Constraints: The Atari 2600, with its meager 128 bytes of RAM and intricate, hand-tuned television interface processor (TIP) programming, was a furnace for ingenuity. Oink! reflects this: the screen is a simple, static side-view with a flip-screen element when moving between material pick-ups. The wolf, a large, multi-colored sprite, and the pig are detailed for the system, with the house walls changing color (yellow for straw, brown for sticks, red for brick) to denote progression—a clear, efficient use of the limited palette. The sound design, notes one critic, repurposes cues from Super Breakout, a common practice on the 2600, but uses them effectively to signal the wolf’s huffing and the pig’s peril.

The Gaming Landscape of 1983: By early 1983, the North American video game market was saturated and nearing the brink of the Great Crash. Consumers were weary of low-quality clones, and retailers were hesitant to stock new titles. Against this backdrop, Activision’s strategy was to publish games with strong, instantly understandable hooks. Oink!’s hook was its fairy-tree premise, a direct appeal to families and children—a demographic increasingly courted by Nintendo’s upcoming Famicom. It positioned itself not as a complex adventure but as a frantic, physical, “arcade-style” experience, as categorized by MobyGames, aiming for immediate engagement in a crowded marketplace.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Futility of Home Improvement

Oink!’s narrative is not one of heroism but of defensive desperation. It strips the classic tale down to its core conflict: the unstoppable force (the wolf) versus the immovable object (the pig’s will to survive). The hero is not triumphant; he is perpetually on the verge of being literally sucked out of his home.

Plot and Characters: The plot is conveyed entirely through gameplay and the manual’s flavor text. The player controls three anonymous “portly porkers” (as the Activision catalog quips) sequentially. Their adversary is “Bigelow B. Wolf” (B.B. Wolf), a name that personifies him as a boastful bully. There is no dialogue, no cutscenes, only the silent, pixelated pantomime of construction and destruction. The manual explicitly states the goal: “score as many points as possible by helping the Pigs patch their houses, thereby protecting them from Bigelow B. Wolf.”

Underlying Themes: The game’s genius and its greatest source of frustration lie in its thematic fidelity. In the fable, the brick house ultimately wins. In Oink!, it is merely the last, most difficult phase before inevitable loss. This creates a powerful theme of progressive futility. The straw house is permeable and quick to fail; the stick house offers slightly more resistance; the brick house, symbol of ultimate security in the story, is here just a longer, more grueling delay. The wolf’s “breath” (rendered as a horizontal beam or tongue) is an unceasing, mechanical force. You are not fighting a sentient foe but a natural disaster given form. The game also explores resource management under duress. Materials appear at the top of the screen, forcing the pig to constantly choose between the hole directly in front of him or a widening breach elsewhere—a classic triage scenario. The “holes” are not just damage points; they are literal voids threatening to erase your character from the playing field.

TV Tropes astutely labels this “The Bad Guy Wins” and “Adaptational Badass,” noting that the wolf’s breath is powerful enough to eventually destroy the brick house—a significant escalation from the source material that re-frames the entire endeavor as a tragic, albeit humorous, delaying action.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Frantic Loop of Patch-and-Panic

Core Gameplay Loop: The gameplay is a masterclass in constrained, high-pressure design. The screen is divided: the wolf occupies the bottom third, the pig’s house (with its three-layer wall) the middle, and the material platform the top. The wolf systematically attacks, removing one “section” of the wall at a time. The pig must climb to the top, grab a patch (which automatically matches the house’s material), descend, and press the button to place it in a hole. If a hole is large enough for the pig to fall through, a life is lost. If the pig’s sprite touches the wolf’s breath beam, he is stunned and rendered vulnerable to falling.

Progression and Scaling: The difficulty curve is relentless and mathematically defined. You start with the straw house. After a set amount of time or damage, you transition to the sticks, then the bricks. Concurrently, the wolf’s attack speed increases. Crucially, the scoring system creates its own pressure: each patch is worth 4 points initially. When the supply of patches on-screen is exhausted, a new row appears, and the point value multiplies (e.g., third row = 12 points per patch). This incentivizes survival not just for longevity, but for exponentially higher scores, pushing players to take risks they otherwise might not.

Game Variations and Multiplayer: This is where Oink! achieves its legendary, if polarizing, status. MobyGames and Wikipedia list three modes:

1. Single-Player: The pure, endless endurance test against the AI.

2. Two-Player Alternating: Players take turns as the pigs, competing for high score. This mode is essentially a score-attack marathon.

3. Two-Player Competitive (Pig vs. Wolf): The celebrated asymmetric mode. One player controls the pig, the other controls the wolf. Critically, the roles alternate after each “catch.” This transforms the game from a solo test of patience into a tactical, psychological battle. The wolf player must strategize which holes to attack to force the pig into the most vulnerable position, while the pig player must outthink their opponent. As the My Brain on Games review states, this mode is where the game becomes “stellar” and a “riotous affair,” precisely because the perceived imbalance (the pig’s constant movement) becomes part of the competitive fun.

Flaws and Innovations: The innovations are clear: the thematic integration, the escalator scoring, and the brilliant Pig vs. Wolf mode. The flaws are equally stark. The single-player campaign is criticized as “mind-numbing” (The Video Game Critic) and a “test of stamina” (Electronic Fun). The core action—climbing up, grabbing, descending, patching—is a repetitive physical loop with little strategic variation beyond triage. The game’s famous lack of fun for some stems from this relentless, unrewarding grind where the player’s powerlessness against the scaling AI is palpable. The controls, while functional, are not snappy, exacerbating the tension.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Charming Simplicity on a Pixelated Farm

Visual Direction: The world of Oink! is a minimalist farmstead. The houses are represented by their colored walls (yellow, brown, red) with no roof or side details—pure abstraction. The pig is a large, rotund, smiling sprite, a stark contrast to the grim task. The wolf is a menacing, multi-colored figure with an elongated snout, his “breath” a distinctive visual element. The art is quintessential Activision: bold, clear, and colorful within the 2600’s severe limitations. The background is a simple blue sky with clouds, changing subtly between houses to denote different times of day or locations, a nice atmospheric touch.

Sound Design: The audio is a perfect companion to the visual simplicity. The main theme is a jaunty, looping melody that ironically contrasts with the player’s anxiety. The sound effects are the star: the wolf’s huff is a rising, pulsating tone that becomes a frantic buzz as he attacks faster. The “patch placed” sound is a satisfying clunk. The pig’s startled oink and the dramatic “whoosh” as he gets sucked out are darkly humorous. One review notes similarities to Super Breakout, but they serve the game’s urgent pacing well.

Atmosphere: The atmosphere is one of cartoonish dread. The visuals are cute, the sounds are silly, but the gameplay is genuinely stressful. This dissonance is the game’s unique charm. You are not exploring a world; you are trapped in a single, escalating crisis. The setting never changes beyond the wall color, reinforcing the feeling of a contained, inescapable battle of attrition.

Reception & Legacy: Critical Divisiveness and Cult Status

Contemporary Reception (1983-84): Oink! arrived to a confused and fragmented market. Critics were split. Tilt (France) gave it 4/6, noting its immediate immersion. Electronic Fun with Computers & Games was scathing (2.5/4), calling it a “moderately difficult” marathon of boredom. The most famous accolade was the “Most Humorous Video Game/Computer Game” award at the 5th annual Arkie Awards in 1984, cited by Wikipedia. This award highlights its recognized quirky charm, even if its gameplay wasn’t universally loved.

Modern Retrospective Reception: The divide persists. The Atari Times praised it as “unique” and “fun” (80%), while Woodgrain Wonderland found it “not the greatest” but compelling enough for “one more game” (58%). The most infamous takedown remains from The Video Game Critic (0%), which savaged its “serious lack of fun” and “mind-numbing” repetition, admitting the graphics are “quite good.” This encapsulates the modern consensus: it’s visually appealing and conceptually brilliant, but its single-player loop is a bridge too far for many. Player ratings on MobyGames (2.9/5) and VideoGameGeek (5.71/10) reflect this middling, niche appreciation.

Legacy and Influence: Oink!‘s direct influence on the industry is negligible. It did not spawn clones or a genre. Its legacy is that of a curated classic, a game whose bold, asymmetric design is studied in discussions of early multiplayer experimentation. It is a beloved entry in the Activision Anthology compilations, where its high-score patch (the “Oinkers” patch for 25,000+ points) is often unlocked at a lower threshold, serving as a neat historical footnote. Its true influence is in proving that even the simplest, most repetitive gameplay loop could be elevated by a brilliantly conceived two-player competitive mode—a lesson echoed decades later in the asymmetrical horror game genre. Its inclusion on “underrated Atari games” lists speaks to its status as a cult artifact for those who appreciate dense, mechanical, head-to-head competition on ancient hardware.

Conclusion: The Pyrrhic Victory of the Pig

Oink! is not a “great” game by conventional metrics. Its single-player campaign is a grueling, repetitive marathon that tests patience more than skill. Yet, to dismiss it entirely is to miss its profound, if narrow, brilliance. Mike Lorenzen and Activision took a public domain story and inverted its moral: the entity we root for is doomed from the start. This creates a unique, tense atmosphere of helpless defiance.

Where Oink! soars—and where it truly earns its historical footnote—is in its “Pig vs. Wolf” competitive mode. This was an early, daring experiment in asymmetric local multiplayer on a home console, predating many celebrated examples by decades. It transforms the game from a dull chore into a psychological duel, where the pig player’s frantic labor is mirrored by the wolf player’s sadistic strategy. This mode alone justifies the game’s existence and secures its place in the attic of gaming history.

In the final analysis, Oink! is a brilliant premise shackled to a monotonous core mechanic. It is a testament to the Atari 2600’s capacity for innovation within severe limits, and a reminder that the seeds of deep, competitive gameplay could be found in the most unlikely of fairy tales. It is a game you don’t play to win, but to endure—and, with a friend, to revel in the chaotic, unbalanced struggle. For that reason, among the hundreds of Atari 2600 titles, Oink! remains a stubborn, squealing, and unmistakably memorable pig in the poke.