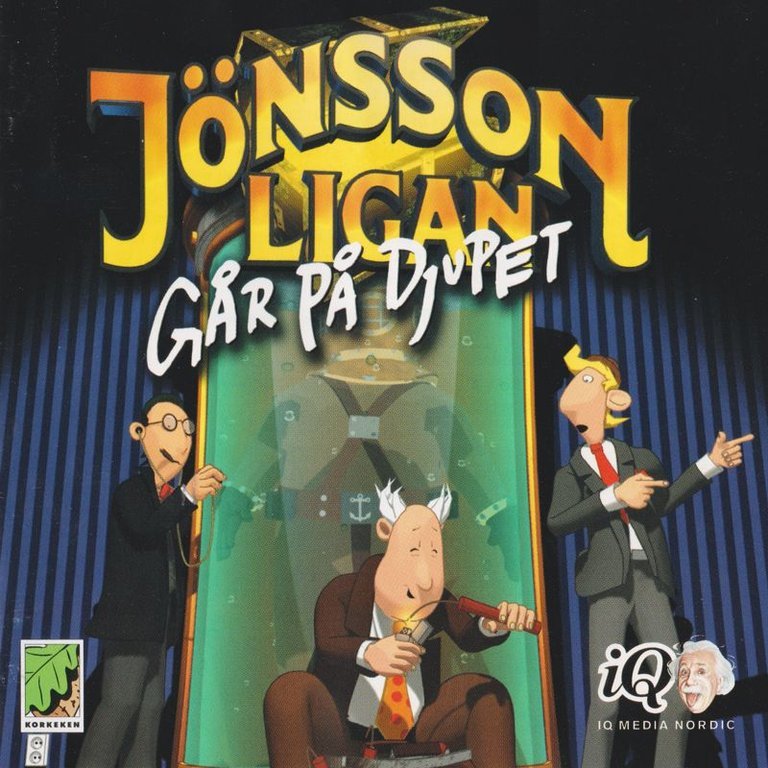

- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: IQ Media Nordic AB

- Developer: Korkeken Interactive Studio AB

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Item interaction, Point-and-click, Puzzle-solving

- Setting: 17th century, Ship, Stockholm’s archipelago, Underwater

- Average Score: 65/100

Description

Jönssonligan: Går på Djupet is a puzzle-solving point-and-click adventure game based on the Swedish comedic film series, featuring the iconic trio Sickan, Vanheden, and Dynamit-Harry. Players control all three characters simultaneously as they share an inventory and move together through underwater environments in Stockholm’s archipelago, exploring the sunken 17th-century man-of-war Spire to uncover its hidden treasure.

Gameplay Videos

Jönssonligan: Går på djupet Reviews & Reception

gamearchives.net (65/100): classic detective-mystery gameplay with quirky humor

Jönssonligan: Går på djupet: A Nautical Nostalgia Trip Through Swedish Gaming’s Forgotten Waters

Introduction: A Smörgåsbord of Specificity

In the vast, often homogenous ocean of late-90s and early-2000s point-and-click adventures, few titles are as uniquely, impregnably Swedish as Jönssonligan: Går på djupet. Released at the very tail end of the genre’s golden age, this game is not merely an adaptation but a cultural artifact—a digital time capsule that封装 (fēngbāo) encapsulates a beloved national film franchise, the technical constraints of its era, and the peculiar charms of a niche regional game development scene. For the uninitiated, it is an impenetrable wall of local humor and context. For the historian, it is a perfect case study in licensed game development, where fidelity to source material can be both a greatest strength and a fundamental design flaw. This review will argue that Går på djupet is a fascinating, deeply flawed curio: a game that succeeds in spirit through its authentic voice and comedic tone but stumbles in execution due to rigid, often counterintuitive design choices, ultimately cementing its legacy not as a genre classic, but as a poignant monument to a specific moment in Scandinavian interactive entertainment.

Development History & Context: A Small Studio, A Big (Sunken) Dream

The Studio and The Vision: The game was developed by Korkeken Interactive Studio AB, a small Swedish team later known as Oblivion Entertainment. The project was a direct sequel to 1999’s Jönssonligan: Jakten på Mjölner, and much of the core team returned, led by Per Demervall. Demervall was not just a game writer/director but a key figure in the franchise’s extended universe, having previously authored Jönssonligan comic books. This continuity of creative vision was paramount; the games were not cash-grabs by a faceless publisher but passion projects from people who understood the characters’ rhythms and the fans’ expectations. The publisher, IQ Media Nordic AB, specialized in media tie-ins, providing the crucial film license that granted access to the iconic characters and, most importantly, the original actors’ voices.

Technological Constraints & The Late-Era Adventure Landscape: 2000 was a year of transition. The point-and-click adventure, once the king of PC gaming, was facing severe market pressure from the rising tides of 3D action and real-time strategy. Budgets were tightening, and Går på djupet bears all the hallmarks of its modest means. It utilizes a top-down, pre-rendered 2D background style, a cost-effective method that avoided the complexities of full 3D navigation. The perspective is essentially static screens with clickable hotspots. The game runs on a Pentium 90MHz system with 16MB RAM—a spec that was already dated in the year 2000—and is distributed on a single CD-ROM. The audio, while featuring full Swedish voice work from the film cast, is limited in quantity and quality, typical of the compression needed for CD-based games of the period. The choice to support both Windows and Macintosh (Mac OS 7.6.1+) was a practical one for a Nordic title, ensuring broader reach in a region where Macs still held significant market share, but it also speaks to a development process prioritizing accessibility over cutting-edge PC exclusivity.

Franchise Context: Går på djupet (“Goes Deep”) is a direct sequel to Jakten på Mjölner (The Hunt for Mjolnir). The predecessor established the core gameplay template: a trio of hapless thieves, a shared inventory, and a Europe-spanning treasure hunt. The sequel’s plot, conceived by Demervall, was originally imagined as a comic book series before being adapted into this game. This origin explains the game’s episodic, quest-log structure and its emphasis on narrative set-pieces over systemic gameplay depth.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Slapstick and Sunken Gold

Plot Synopsis in Detail: The game’s plot, a new story not directly adaptating any film, begins in media res. Charles-Ingvar “Sickan” Jönsson, the group’s fast-talking, perpetually scheming mastermind, has just orchestrated a heist on Wall-Enberg’s Chips Factory. The goal: a safe containing 2.3 million kronor in illicit cash. The heist predictably fails. In the chaotic escape, Sickan, hiding in a ventilation shaft, overhears the smug financier Wall-Enberg on his mobile phone. Wall-Enberg is lamenting (or perhaps boasting about) a wreck resting on the bottom of the Stockholm Archipelago: the 17th-century man-o’-war Spire, which holds a priceless treasure—a gold-encrusted bible. The scent of unimaginable wealth overrides the failure of the chips caper. The new, definitive score is born: find the Spire, salvage the bible, and secure their retirement.

The adventure then unfolds as a multi-stage operation. The trio must first gather specialized deep-sea diving equipment (a task requiring classic adventure-game item combination and misdirection). Then, they navigate a series of coastal locations and underwater environments, solving environmental puzzles to pinpoint the wreck’s exact coordinates. Their path is obstructed, as ever, by their nemesis Wall-Enberg and his dimwitted enforcer Biffen, who are also on the trail of the treasure. The climax involves a race against Wall-Enberg to the wreck site, a frantic underwater puzzle sequence, and a typically farcical resolution where the “treasure” is perhaps not what it seems, or its recovery leads to a new, equally ridiculous predicament—true to the spirit of the films.

Characterization and Dialogue: The game’s greatest asset is its verbatim recreation of the film’s character voices and comedic dynamics.

* Sickan (Hans Wahlgren): His dialogue is a masterclass in sardonic, pseudo-intellectual bluster. He narrates his own plans with elaborate, jargon-filled confidence that inevitably unravels. His catchphrase, “Allt är tajmat och klart in i minsta detalj” (“Everything is timed and planned down to the smallest detail”), is a recurring ironic motif. In the game, his lines are a blend of instructions, insults directed at Vanheden and Harry, and fourth-wall-breaking asides.

* Ragnar Vanheden (Ulf Brunnberg): The strong, silent type (though not entirely silent). His humor is physical and deadpan. His primary function in the gameplay narrative is to be the one who handles heavy lifting—often literally—and to be the butt of Sickan’s jokes about his lack of brainpower. His few vocal lines are grunts of agreement or confusion.

* Harry “Dynamit-Harry” Kruth (Björn Gustafson): The volatile, explosives-obsessed heart of the group. His comedy stems from his single-minded fixation on using dynamite for every problem, no matter how small, and his childlike enthusiasm for pyrotechnics. His dialogue is a mixture of explosive proposals (“Should we just blow it up?”) and melancholic reflections on his past failures. His character provides a crucial counterbalance to Sickan’s schemes.

* Supporting Cast: The film’s returning antagonists are present. Wall-Enberg (Per Grundén) is the prickly, wealthy adversary, and Biffen (Weiron Holmberg) his oafish muscle. Doris (Birgitta Andersson) and other film regulars make cameo appearances, reinforcing the licensed authenticity.

Themes: The narrative explores classic Jönssonligan themes:

1. Greed vs. Incompetence: The pursuit of vast wealth by profoundly inept criminals. The treasure is a MacGuffin that exposes their flaws.

2. Found Family/Loyalty: Despite constant bickering, the trio are utterly dependent on each other. The shared inventory mechanic, for all its gameplay flaws, is a literal representation of their codependency.

3. Anti-Authority Farce: Wall-Enberg represents corrupt, respectable capitalism. The Jönssonligan are chaotic, amoral anarchists. The game positions the audience’s sympathies firmly with the chaotic trio.

4. The Absurdity of Planning: Sickan’s elaborate plans are constantly undermined by mundane details or Harry’s explosive impulses. This is the core comedy engine, translated directly from film to game through dialogue and puzzle design.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Shared Burden

Core Loop: Går på djupet is a classic 1990s point-and-click adventure with a major structural quirk. The player controls the entire trio simultaneously. They move as a single unit across the screen. There is no individual character selection. The cursor is used to navigate environments (walking to locations) and to interact with objects via a single action verb (usually “Använd” – “Use” or “Interact”). The interface is minimalist: a bottom panel displays the characters’ portraits and a single, shared inventory slot (Harry’s bag, visually depicted).

Puzzle Design & The Central Flaw: The shared inventory system is the game’s defining mechanical trait and its greatest point of failure. All items found by any character are deposited into the one bag. When using an item, you select it from the bag, and it is “used” on the environment by the collective trio. This creates a unique, tense dynamic: an essential item needed for a later puzzle can be accidentally used up in an earlier, optional interaction. There is no “drop” command to unequip items safely. The game does not offer clear feedback on which items are still critical. This leads to frequent, unfair game-over states or unwinnable situations where the player has no way of knowing a vital tool was consumed hours earlier. It’s a brilliant representation of groupthink and resource mismanagement—a thematic match—but a brutal, frustrating gameplay experience.

Structure & Progression: The game is divided into distinct locations (e.g., “Chips Factory,” “Harbor,” “Archipelago Island,” “Underwater”). Each location is a single-screen or multi-screen area with a set of objectives. Progression is purely item-based and puzzle-based. There is no character progression, stats, or combat. The only “opposition” is environmental puzzles and the occasional timed sequence or misdirection by Wall-Enberg’s goons, who act more like moving obstacles than adversaries. The “detective/mystery” narrative tag is accurate in the sense that you must uncover clues (coordinates, map pieces) through exploration and item combination, but it is not an investigation in the Police Quest or Gabriel Knight mold.

Innovation vs. Flaw: The innovation of the collective movement is clever from a narrative standpoint—it forces the player to think as the group. However, it limits puzzle complexity. You cannot have a puzzle requiring two characters to be in different places simultaneously. The entire design is built around this constraint. The “innovation” is therefore a severe limitation. The game’s puzzles often rely on “moon logic”—using an item in a way that is absurdly specific and non-intuitive (e.g., using a fish to bribe a door, using dynamite to create a makeshift snorkel). This was common in adventure games but is exacerbated here by the shared inventory, making experimentation dangerous.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Capturing a Swedish Summer on a CD

Visual Direction & Art Style: The game employs a hand-drawn, 2D isometric/top-down aesthetic. The backgrounds are beautifully painted, charmingly stylized representations of their real-world inspirations (a Stockholm alley, a classical temple, a gloomy underwater wreck). The color palette is rich but constrained by the era’s 256-color limitation, giving it a slightly muted, almost storybook quality. The character sprites are simple but animated with personality: Sickan’s strut, Harry’s restless energy, Vanheden’s hulking presence. The art successfully translates the live-action film’s settings into a playful, illustrative game world. The different locations have distinct visual identities—the warm, busy reds of the chip factory, the cool blues of the archipelago, the murky browns of the ocean floor—which provides strong environmental storytelling.

Sound Design & Voice Acting: This is the game’s undisputed crown jewel. The original film actors—Wahlgren, Brunnberg, and Gustafson—reprise their roles with gusto. Their voices are instantly recognizable to any Swedish viewer and imbue the game with an authenticity no other asset could match. The delivery of the script (by Per Demervall) captures the characters’ cadences perfectly. The soundscape supports this with simple but effective effects: clinking bottles, crashing waves, the click-clack of item manipulation, and Harry’s signature “BANG!” sound effect. The music is functional and catchy, with leitmotifs for different areas (e.g., jaunty carnival tunes for the harbor, tense strings for underwater), but it is not memorable or dynamically layered. Its primary role is to set a light, adventurous mood without distracting from the dialogue.

Atmosphere & Cohesion: The combination of familiar voices, painterly locations, and slapstick sound effects creates a surprisingly cohesive atmosphere. It genuinely feels like stepping into a Jönssonligan film. The humor comes through not just visually but aurally. The world is a whimsical, slightly exaggerated version of Sweden where a treasure hunt feels like a summer vacation caper. This consistent tone is the game’s greatest achievement and its saving grace when the puzzles become maddening.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Classic By Default

Contemporary Reception: The game received a mixed but generally positive reception within Sweden, where the film franchise is iconic.

* Göteborgs-Posten awarded it 4 out of 5, praising its faithful humor and enjoyable adventure.

* TT Spektra noted approvingly that “Jönssonligan functions surprisingly well as a computer game.”

* Aftonbladet, Sweden’s largest tabloid, was harsher, giving it 2 out of 5, criticizing its lack of originality and cumbersome logic.

This critical split mirrors the player experience: the game is either a delightful nostalgia trip or a frustrating exercise in outdated design. The MobyGames user rating of 3.2/5 (based on only 2 ratings) and the dearth of professional reviews on sites like MobyGames itself underscore its obscurity outside Sweden.

Commercial Performance & Sequel Status: Exact sales figures are scarce, but the fact that a direct sequel—actually this very game, Går på djupet—was released in 2000 following Jakten på Mjölner (1999) suggests the first title was at least a modest commercial success within its target market. A developer comment cited in Wikipedia implies first-month sales around 100,000 copies, a significant number for a small-market, licensed Swedish adventure. This sequeling indicates a publisher confident in the niche.

Legacy and Historical Significance:

1. A Peak of Licensed Adaptation: For its time, Går på djupet represents a high-water mark for faithful, high-quality voice-acting in licensed games. It demanded and received the original cast, something many international tie-ins failed to secure. It treated the license with respect.

2. Case Study in Constraint: It is a textbook example of how design constraints (shared inventory) can become thematic strengths but gameplay weaknesses. It is frequently cited in discussions of “moon logic” and unwinnable states in adventure games.

3. Niche Cultural Preservation: It digitally archived a specific Swedish comedic archetype—the Jönssonligan—for a new medium. For historians of Scandinavian media, it is a point of intersection between cinema, comics, and interactive software.

4. Obscurity and Preservation: Today, it is abandonware, preserved on sites like the Internet Archive and My Abandonware. Its legacy is sustained not by commercial re-releases but by dedicated fan preservation efforts and nostalgic retrospectives. It is virtually unknown internationally, a testament to the powerful barrier of language and cultural context in game history.

5. Influence: Its direct influence on the global industry is negligible. However, within Sweden, it demonstrated that a home-grown, non-English adventure game with a local license could be viable, paving the way (however narrowly) for other Nordic studios. The shared-character mechanic, while flawed, was an attempt at a distinctive systemic identity.

Conclusion: A Flawed Gem in the Deep Blue

Jönssonligan: Går på djupet is not a lost masterpiece. By any objective, cross-cultural standard, its puzzles are obtuse, its mechanics are unforgiving, and its appeal is severely limited by its language and franchise specificity. Yet, to dismiss it entirely is to miss its historical and cultural value. It is a brilliantly voiced, passionately crafted, and mechanically reckless time capsule. It captures a moment when a beloved film franchise was translated, with immense care for its soul but imperfect understanding of interactive design theory, into the burgeoning world of CD-ROM gaming.

Its place in video game history is not on a pedestal but in a curated display case. It belongs to the annals of regional game development, showcasing how local studios leveraged home-grown IP. It belongs to the late golden age of point-and-click, illustrating both the genre’s charming tradition of puzzle absurdity and its fatal tendency towards player-hostile design. And most importantly, it belongs to the story of Jönssonligan itself—a digital footnote that proves the gang’s antics were versatile enough to span from the silver screen to the computer monitor, for better and for worse.

For the vast majority of gamers, it is an academic curiosity, perhaps worth a glance for its anthropological significance. For the Swedish nostalgic or the dedicated adventure game historian, it is a frustrating but endearing dive into waters where comedic timing battles against unfair puzzle design, and where the sound of Hans Wahlgren’s voice saying “Allt är tajmat…” is enough to make the swim worthwhile, even as you repeatedly drown in a shared inventory pool of your own making. It is, in the end, a perfect Jönssonligan adventure: the plan is audacious, the execution is messy, and you’ll probably end up covered in metaphorical (and possibly literal) mud, but you’ll have a story to tell.