- Release Year: 2006

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Trumgottist Entertainment

- Developer: Trumgottist Entertainment

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Graphic adventure, Puzzle

Description

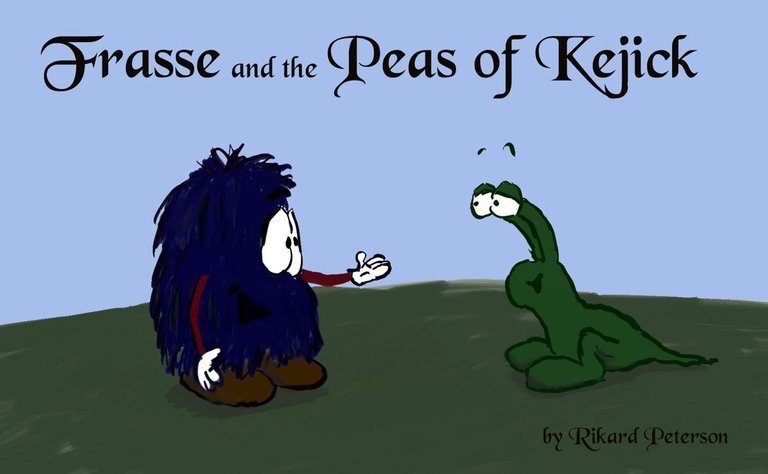

Frasse and the Peas of Kejick is a freeware third-person point-and-click adventure game where players control Frasse, a little blue hairy monster, and his friend Gurra on a quest to find the mythical Peas of Kejick for a king’s reward. Set in a whimsical, cartoon-inspired world, the game emphasizes puzzle-solving through character-switching: Frasse handles inventory and item interaction, while Gurra excels at dialogue, creating a humorous and engaging experience.

Frasse and the Peas of Kejick Free Download

Frasse and the Peas of Kejick Guides & Walkthroughs

Frasse and the Peas of Kejick Reviews & Reception

jd-adventuregamereviews.blogspot.com : The game really does excel visually.

retro-replay.com : Frasse and the Peas of Kejick offers a classic third-person point-and-click adventure experience that expertly blends character switching with environmental puzzles.

Frasse and the Peas of Kejick: A Hidden Gem of Indie Adventure Game Ingenuity

Introduction: The Unassuming Power of a Blue Monster

In the vast, often-overlooked archives of freeware and shareware gaming, certain titles emerge not as commercial titans but as pure, concentrated expressions of a creator’s vision. Frasse and the Peas of Kejick (2006) is one such title—a game that could easily be dismissed as a cute, ephemeral diversion were it not for the profound cleverness embedded in its design and the surprising depth of its affection for the golden age of point-and-click adventures. Created almost single-handedly by Swedish developer Rikard Peterson under the Trumgottist Entertainment banner, this SLUDGE engine title transcends its modest origins to deliver an experience that is at once warmly nostalgic and refreshingly innovative. Its thesis is simple yet powerful: that the heart of the adventure genre—charismatic characters, inventive puzzles, and a world brimming with personality—can thrive independent of blockbuster budgets, so long as the creator possesses a sharp understanding of the form’s core pleasures. This review will argue that Frasse and the Peas of Kejick is a masterclass in constrained development, a game where every system, from its dual-protagonist mechanic to its vibrant, comic-book aesthetic, serves a unified purpose, cementing its legacy as a cult classic and a vital artifact of the mid-2000s indie adventure boom.

Development History & Context: A Bedroom Epic Born from Discarded Ideas

The context of Frasse and the Peas of Kejick is inseparable from the ethos of its creation. As stated in its MobyGames trivia, the game’s design document began as a “collection of ideas that were discarded for another (still unreleased) game because they were too silly or just didn’t fit.” This origin story is crucial. It reveals a developer unshackled from commercial pressures, mining the rejects of one project to birth another. The result is a game that feels unapologetically, gleefully silly—a quality that becomes its greatest strength. Rikard Peterson assumed nearly every major role: designer, artist, musician, and programmer. The credits list 27 contributors, but the core “Game by” credit is his alone, with others primarily in beta testing and minor asset contributions (“some graphics slightly stolen from” Dietrich Squinkifer, and “some ideas stolen from” Romain Gaillard and L.J. Wischik). This highlights the collaborative yet intensely personal nature of the freeware scene, where credit is generously shared but vision remains singular.

Technologically, the game was built with the SLUDGE engine, a less mainstream alternative to the era’s dominant Adventure Game Studio (AGS). As noted by a forum user on Curly’s World, “games made with it are always ten times more colourful than AGS games.” This observation points to SLUDGE’s handling of 2D art and palette, which Peterson exploited to create a world of saturated, joyful color. The development spanned from 2003 to its release in February 2006, placing it in a fascinating period for adventure gaming. The LucasArts golden age had waned, and the genre was in a commercial lull, sustained largely by a passionate community of independent creators. Frasse was thus part of a vital underground pipeline, distributed via sites like Curly’s World of Freeware and Caiman, that kept the adventure spirit alive. Its subsequent Special Edition (2010), which added voice acting and cross-platform support (Mac/Linux), demonstrates Peterson’s ongoing commitment and the game’s enduring appeal within this niche ecosystem.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Deconstructing the Fetch Quest

On the surface, Frasse and the Peas of Kejick adheres to the most classical of adventure game premises: a royal summons, a magical MacGuffin, and a perilous journey. King seeks legendary Peas of Kejick (needed for “national security”), offers reward, lowly hero accepts. However, Peterson uses this archetypal scaffold to execute a series of nimble thematic subversions and character-driven jokes.

Plot Architecture and the Subversion of Expectation: The narrative is structurally sound, divided into distinct chapters: the peaceful hometown (Frasse’s abode), the journey to Kejick Island (involving a rescue andtransport), the island’s surface and caves, and the final confrontation and return. The genius lies in the twist mentioned by both the developer (in forum posts) and reviewers. The player, after overcoming the dragon and securing the Peas, expects the game to conclude upon delivery to the castle. Instead, the “ending” reveals a new layer of conflict or irony, transforming the quest from a simple fetch mission into a commentary on the nature of the reward and the Peas’ true purpose. This narrative sleight-of-hand elevates the story from functional to memorable.

Character Dynamics: Complementarity as Core Philosophy: The relationship between Frasse and Gurra is the game’s emotional and mechanical cornerstone. Frasse is the naive, tangible, and hands-on optimist. His “blue hairy monster” design, as described in numerous reviews, projects “cuteness” and approachability. Gurra, the “green slug-like frog” with no arms, is the witty, pragmatic, and socially astute counterbalance. Their dynamic is not one of rivalry but of symbiotic necessity. The game’s puzzles constantly force the player to leverage this synergy: Frasse must physically obtain items and interact with the environment, while Gurra must negotiate, gather information, and use his unique “kick” ability. This design reinforces a subtle theme: diversity of skill is indispensable for overcoming complex challenges. They are not two heroes but one unit with two complementary modes of operation.

Humor and Tone: The game’s humor is described as “subtle” (Game Tunnel), “fun” rather than laugh-out-loud funny (JD’s Review), and possessing a “wonderful ‘cartoony’ feel” (Abandonia Reloaded). It emerges from character quirks (the bickering Zaks who won’t move, the Loom guy in the bar), situational irony, and the inherent absurdity of Gurra’s limbless condition. It’s a non-violent, family-friendly humor rooted in character and world-building, aligning with the developer’s stated goal of making something “completely traditional” in story and gameplay but with a “fresh and surprising” feel.

Thematic Underpinnings: Beyond the adventure tropes, themes of friendship, resourcefulness, and questioning authority (the King’s motives are suspect) permeate the game. The final twist, whatever its specific nature, inevitably prompts the player to reconsider the entire journey’s purpose, a sophisticated narrative move for such a succinct title. The game posits that the journey and the bond forged between the protagonists are more valuable than the promised reward—a classic yet effective adventure game morality.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Duel of Minds and Mechanics

Frasse and the Peas of Kejick’s gameplay is where its design philosophy crystallizes into engaging, interactive form. It represents a significant evolution on the standard point-and-click formula through its mandatory, seamless dual-character control.

Core Loop and Interaction Model: The player navigates third-person environments with a single cursor. The interface is brilliantly minimalist: clicking on a character (Frasse or Gurra) switches control. Upon clicking a hotspot (object, character, or environment element), contextual icons appear over the active character’s miniature portrait at the top of the screen: an eye (Look), a mouth (Talk/Eat), and a hand (Use/Take). For Gurra, the hand is replaced by a foot (Kick). This system achieves two things: first, it eliminates UI clutter, keeping the focus on the vibrant game world. Second, and more importantly, it physically embodies the character’s limitations and strengths. You don’t just select “Frasse” from a menu; you are Frasse, and must think with his hands. You don’t just select “Gurra”; you become the leg that must kick or the mouth that must charm.

Puzzle Design: Synergy and Scalable Difficulty: Puzzles are the game’s backbone and receive the most detailed commentary from reviewers. They range from straightforward inventory combinations (Frasse-find key, Frasse-use key) to complex, multi-stage problems requiring precise sequencing of both characters’ actions. The “cave part” with its “colorsystem” was explicitly cited by a player (Chroelle) and acknowledged by Peterson as a potentially confusing logic puzzle—a rare point of friction. Peterson’s comment that “the real puzzles in that area involve the door” suggests he intended the color maze as atmospheric set-dressing against a more conventional lock puzzle, a slight misalignment between designer intent and player interpretation.

A critical innovation is the existence of multiple solution paths. JD’s review notes there is “actually an alternative solution for those who either can’t or don’t wish to work out the answer for themselves.” This is a hallmark of thoughtful adventure design, reducing frustration while preserving the satisfaction of discovery. The puzzle difficulty is described as “moderate” to “quite tricky” (Adventurearchiv, Game Tunnel), with some requiring walkthrough assistance. This scaling creates a game that is accessible to younger players (as Pater Alf notes) but also offers substantial challenge for veterans.

Character Progression & UI: There is no traditional RPG-style stat progression. “Progression” is purely inventory and knowledge-based. Frasse’s inventory is the game’s only persistent item pool, accessed via right-click or a bag icon. The UI’s elegance is its invisibility. The lack of a verb coin (like Day of the Tentacle) is replaced by the character-specific icons, which feels more integrated. The sole significant UI critique from the community was a momentary confusion about character switching (Chroelle’s initial post), which stemmed from a story trigger (needing to show the king’s note to Gurra first) rather than a flawed interface. This indicates the system is intuitive once its small narrative prerequisites are met.

Innovation within Constraint: The game’s greatest innovation is also its simplest: mandatory, constant character switching as a puzzle mechanic. Most adventure games with multiple playable characters (e.g., Maniac Mansion, Day of the Tentacle) allow independent control but rarely make their unique physical traits the central puzzle key for every significant obstacle. Gurra’s lack of arms isn’t a cosmetic detail; it’s the defining constraint that shapes every interaction. This system transforms a narrative device into a relentless gameplay engine, forcing constant lateral thinking. “Can Gurra talk to this? No, he’s too shy. Can Frasse use that? He can’t reach it. Aha, we need to get Gurra to kick the stool over so Frasse can climb.” This is elegant, systemic design.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Cartoon Heart of Kejick

The sensory presentation of Frasse is arguably its most universally praised attribute and the primary vehicle for its “cartoony” charm.

Visual Direction and Art Style: Peterson’s graphics are hand-drawn, vibrant, and intentionally simplistic. They avoid the pitfalls of “simple” graphics by embracing a consistent, illustrative style reminiscent of children’s book art or animated shorts. Character designs are iconic: Frasse’s round, blue, fuzzy form radiates friendliness; Gurra’s green, limbless, expressive body (with large, emotive eyes and eyebrows) is a masterclass in conveying personality without conventional limbs. Backgrounds are colorful and detailed, with a palpable sense of place—from the cozy, warm interiors of the hometown bar to the chilly, mysterious blues and greys of Kejick mountain. As the Retro Replay analysis notes, “Color palettes shift to reflect mood,” demonstrating an advanced understanding of environmental storytelling for a 2D adventure.

Animation is smooth and expressive. The “little touches”—Frasse dozing on his branch, the blinking animations, the way characters bounce with excitement—give the world a living, breathing quality. Some scenes may show less polish (JD’s note on “close up shots”), but the overall consistency is remarkable for a solo project. The visual design successfully makes the world feel safe, whimsical, and explorable, perfectly suiting the non-violent, puzzle-focused gameplay.

Sound Design and Music: The audio is a standout feature, frequently highlighted in reviews. The game features a “different piece of music for each area” (multiple sources), a significant achievement for a freeware title and a key contributor to atmosphere. These tunes are melodic, memorable, and thematically appropriate, providing auditory landscapes that enhance the visual ones. The music is generally “a pleasure to listen to” (Abandonia Reloaded) and encourages exploration just to hear new tracks. Sound effects are used sparingly but effectively for interactions (clinks, rustles, comedic squawks). The complete absence of voice acting (in the original release) is a constraint turned into a stylistic choice, focusing the player’s attention on the written dialogue and character animations, which are expressive enough to carry emotional weight.

Atmosphere and Cohesion: The combination of bright visuals, cheerful music, and non-violent, humorous writing creates a uniquely welcoming atmosphere. There is no grimdark edge, no sudden scares (outside of maybe a dragon). It is an adventure game you could comfortably imagine a family playing together. This tonal consistency is total; every element reinforces the other. The world feels cohesive because its rules—both gameplay and tonal—are clearly defined and maintained.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Classic Forged in the Freeware Forge

Upon its 2006 release, Frasse and the Peas of Kejick was met with a warm, if modest, reception from the freeware and indie adventure community.

Critical Reception: The five critic reviews aggregated on MobyGames average 81%, a strong score indicating genuine appreciation. Reviews were uniformly positive in tone, with Abandonia Reloaded’s perfect score epitomizing the response: “a lovely adventure game… thoroughly enjoyed it from start to finish.” Common threads in criticism include:

* Praise for its LucasArts hommage: “Adventure in LucasArts-stijl” (Gameplay Benelux).

* Admiration for its unique interface and puzzle design: “Using mini Frasses/Gurras as the game interface is a refreshing idea” (Abandonia).

* Commendation for its charm and humor: “Cute and colourful” (multiple sources), “funny” (Adventurearchiv).

* Critiques of specific difficulty spikes: The cave color puzzle and some “quite difficult puzzles” (Game Tunnel).

* Minor technical or aesthetic nits: Close-up graphics less polished, potential language barrier (Freegame.cz review notes it’s in English only).

Player reception, based on the few MobyGames player ratings, is equally strong (4.4/5), though with even fewer reviews. Forum discussions on sites like Curly’s World show engaged players, solving puzzles and discussing specifics (like the character-switching bug), indicative of an active, if small, community.

Commercial and Availability Context: As a freeware title, “commercial success” is irrelevant. Its “business model” is its cultural model: free distribution, word-of-mouth promotion, and lasting availability via archives like the Internet Archive and dedicated freeware hubs. Its inclusion in the “Classic PC Games” collection at the Internet Archive testifies to its preservation as a noteworthy freeware artifact.

Legacy and Influence: Frasse’s direct influence on the broader industry is minimal due to its niche status. However, its legacy is significant in several ways:

1. A Testament to the SLUDGE Engine: It stands as one of the most polished and praised titles made with SLUDGE, an engine that, as noted, became open source in 2008. It demonstrated the engine’s capability for vibrant, colorful adventures.

2. A Paradigm of Solo/Paid-Labor-of-Love Development: In an era before Steam’s indie explosion, Frasse is a prime example of a “bedroom developer” creating a complete, competent, and charming commercial-quality adventure entirely in spare time. Its existence likely inspired others in the freeware scene.

3. The Dual-Character Mechanic as a Design Artifact: While not the first game with multiple protagonists, its implementation—where character difference is the central, constant puzzle—is exceptionally clean and focused. It serves as a case study in how to build a game’s core puzzle logic around a single, elegant systemic constraint.

4. Cultivation of a Specific Audience: It carved out a dedicated niche among adventure fans seeking non-violent, humorous, challenging, and aesthetically distinct experiences. Its mention in “best free adventure games” lists has persisted.

5. The Unfulfilled Trilogy: Peterson’s forum posts about planning “two sequels” to elaborate on the story and world, while nothing has materialized as of the latest data, speak to the game’s role as a passion project with greater narrative ambitions. Its status as a potential “first part” adds a layer of historical curiosity.

Conclusion: A Definitive Verdict on a Delightful Curiosity

Frasse and the Peas of Kejick is not a lost masterpiece that reshaped the gaming landscape. It is, however, an indisputably masterful freeware adventure game and a perfect example of its subgenre. Its place in video game history is not in the mainstream canon but in the cherished annals of the community-driven, passion-first indie scene that sustained the adventure genre through its leanest years.

Its strengths—a brilliantly integrated dual-character puzzle system, a vibrant and cohesive art style, a clever and affectionate script, and a satisfying narrative arc with a genuine twist—outweigh its few flaws, which are mostly the inevitable trade-offs of solo development (a potentially obscure puzzle, minor graphical inconsistencies). The game delivers exactly what it promises: a humorous, challenging, and heartwarming journey that respects the player’s intelligence and the legacy of LucasArts while carving its own unique identity.

For the historian, it is a valuable document of mid-2000s freeware development, showcasing the capabilities of the SLUDGE engine and the sustainable model of distributed, cost-free creativity. For the player, it remains a readily accessible, endlessly charming way to spend three to four hours. Final Verdict: Frasse and the Peas of Kejick is an essential download for any adventure game aficionado. It is a testament to the enduring power of a great idea, executed with love and wit, proving that a blue furry monster and his armless friend can, against all odds, carry one of the most clever and heartfelt quests ever packed into 10 megabytes. It deserves its 81% critical score and its loyal cult following. A true hidden gem.