- Release Year: 2012

- Platforms: PSP, Windows

- Publisher: Ghostlight Ltd., Starfish-SD Inc.

- Developer: Opera House Inc., Pleocene Co., Ltd., Starfish-SD Inc.

- Genre: RPG

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Character classes, Dungeon-crawler, Grinding, Loot, Party-based, Quests, Turn-based combat

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 64/100

Description

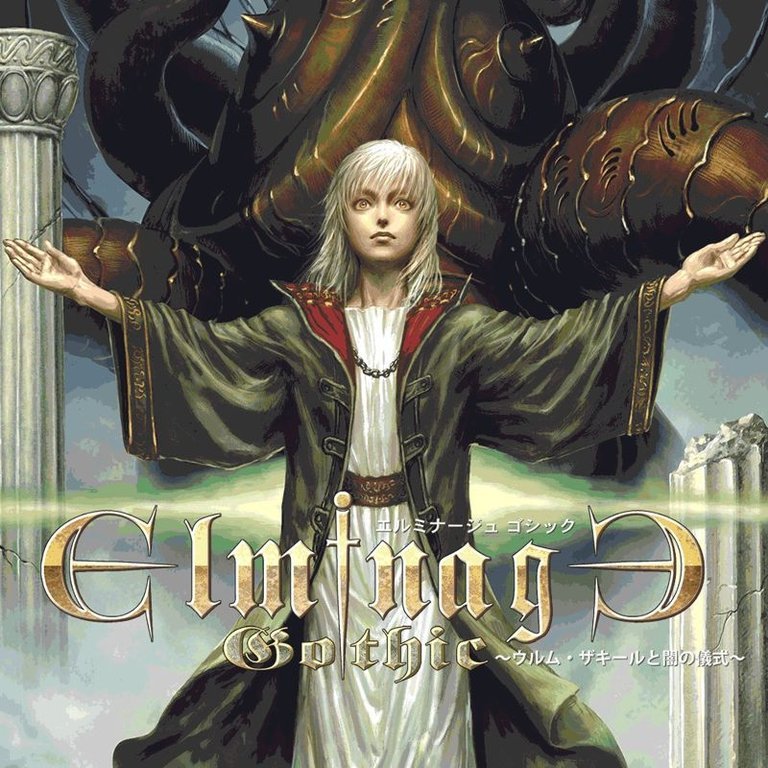

Elminage: Gothic is a first-person dungeon-crawler RPG set in a fantasy world where Great gods and Dark gods wage war through human faith. Players assemble a party of up to six characters from sixteen classes, such as Hunter and Valkyrie, to explore perilous dungeons, fight over 400 monster types, complete quests, and collect more than 600 items, with punishing difficulty that demands grinding and strategic combat, all modeled after classic titles like Wizardry.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Elminage: Gothic

PC

Elminage: Gothic Cracks & Fixes

Elminage: Gothic Guides & Walkthroughs

Elminage: Gothic Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (60/100): If you’re a fan of old-school Wizardry, and don’t mind delving into the B-grade of the genre, then like me you’ll get a kick out of this even as you grumble about its faults.

rpgwatch.com : This game is not meant to be your friend, it is meant to defeat you. Only those with iron wills should continue on.

rpgsite.net : This takes dungeon crawling to the next extreme. Get that graph paper ready.

Elminage: Gothic: A Study in Niche Mastery and Punishing Design

Introduction: The Last Bastion of Formulaic Fidelity

In an era of accessible, hand-holding RPGs and streamlined dungeon crawlers, Elminage: Gothic stands as a defiant, anachronistic monument. Released in Japan for the PlayStation Portable in 2012 and later localized for PC by Ghostlight in 2014, this fourth entry in Starfish-SD’s Elminage series is not a game that seeks to innovate or appeal broadly. Instead, it is a meticulous, almost reverential, recreation of the brutal, cerebral dungeon-crawling ethos pioneered by Wizardry I-III. Its thesis is simple: true depth and reward arise only from overcoming overwhelming odds through meticulous preparation, strategic party building, and dogged persistence. This review will argue that Elminage: Gothic is a masterclass in specialized game design—a game that succeeds brilliantly within its self-imposed constraints but remains fundamentally, perhaps intentionally, inaccessible to all but the most dedicated masochists of the genre.

Development History & Context: A Series forged in Pressure

Elminage: Gothic exists at a crossroads for its franchise. The series began in 2008 with Elminage: Yami no Miko to Kamigami no Yubiwa (developed by Opera House) and quickly gained a reputation in Japan for its faithful adherence to classic dungeon-RPG (DRPG) mechanics and exceptional balance. However, a pivotal moment occurred after Elminage II (2009). Series producer Komiyama Daisuke, who oversaw scenario, monster design, and core systems, was laid off after petitioning for more development resources—a move that created significant fan anxiety about the series’ future. Elminage III (2011) was released amidst this turmoil and received mixed reviews for suffering balance and polish issues.

Elminage: Gothic (2012) was therefore the first main entry developed solely by Starfish-SD Inc. following this internal shake-up. Technologically, it was bound by the PSP’s limitations, resulting in low-poly 3D models and a 480×272 resolution. Its design philosophy, however, doubled down on the classic formula: first-person, grid-based movement, a THAC0-derived combat system, and extreme difficulty. The 2014 PC port by Ghostlight was a critical intervention, increasing resolution, improving the user interface, and—most importantly—providing a complete English translation for the first time in the series’ Western releases. This port placed the game within a very specific 2014 context: a time when the DRPG genre was seeing a small resurgence via titles like Etrian Odyssey and Demon Gaze, but few games embraced the sheer, unadulterated hardship of the 1980s PC originals. Gothic was not a revival; it was a preservation.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Atmosphere Over Plot

The narrative of Elminage: Gothic is intentionally skeletal, serving primarily as a scaffold for dungeon exploration. The premise—a clash between Great Gods and Dark Gods, with human faith as the battleground—is delivered through sparse introductory text and occasional NPC dialogue. The immediate hook is a crisis in the realm of Ishmag: monsters pour from the caves of Tsun-Kurn, heralding the forbidden ritual to revive the ancient evil Ulm Zakir. The player’s party of adventurers is dispatched to investigate and stop it.

Themes are conveyed less through plot and more through environmental storytelling and atmosphere. The subtitle, Ulm Zakir to Yami no Gishiki (“Ritual of Darkness and Ulm Zakir”), signals a gothic, Lovecraftian shift for the series. Dungeons are not mere fantasy labyrinths but ritualistic sites of cosmic horror—filled with surreal, disturbing monsters that feel more like entities from a nightmare than traditional fantasy beasts. This aligns with the game’s title: Gothic implies a focus on decay, dread, and the macabre. The minimal plot allows the dungeons themselves to become the primary narrators. Discovering creepy, lore-rich notes or encountering strange, silent entities in a hidden chamber builds a sense of oppressive mystery that a convoluted main story would only dilute.

Critically, the Wikipedia entry notes a key reception point: Gothic’s text writing has “little to no reference anymore to the past releases.” This deliberate break from the Elminage series’ established lore was jarring for Japanese fans. It suggests Gothic was conceived as a thematic soft-reboot, prioritizing a darker, more self-contained tone over series continuity. The story is a catalyst, not a destination. Its success lies in creating an oppressive, enigmatic atmosphere that makes the枯燥 ( tedious) grind of exploration feel like a descent into genuine, unfolding horror.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Architecture of Austerity

Elminage: Gothic’s gameplay is a masterclass in systemic austerity, where every mechanic reinforces the core tenet: survival is a privilege, not a guarantee.

1. Party Creation and the Alignment System:

Character creation is astonishingly open yet brutally restrictive. Players choose from 5 races (Human, Elf, Dwarf, Gnome, Hotlet) and a staggering 16 classes (Hunter, Thief, Summoner, Valkyrie, etc.), with gender and alignment (Good, Neutral, Evil) options. Alignment is not cosmetic; it gatekeeps classes. A “Good” character cannot become a Ninja, for instance. This creates profound, permanent strategic branching. The class-switching system, a series staple, allows a character to advance in a new class upon meeting stat requirements, retaining HP and up to three levels of prior spells but resetting to Level 1. This encourages multi-class builds (e.g., a Fighter to gain HP, then switching to Cleric for spells) but comes with the severe penalty of accelerated aging—each switch adds a year, leading to potential stat decline in later life stages. It’s a brilliant, punishing metaphor for the cost of versatility.

2. Combat: THAC0 and Turn-Based Tension:

Combat uses a phase-based, turn-order system derived from Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. Each participant’s Agility stat determines initiative within a round. The “THAC0” (To Hit Armor Class 0) system means attack rolls must exceed a target’s Armor Class to hit. There are no level scalings; a low-level party in a high-level dungeon will be obliterated. The six-character party is arranged in two rows (front/back), with weapon ranges and spells dictating targetable rows. This formation management is critical. The combat is brutally efficient: enemies hit hard, status effects like petrification, paralysis, and level drain are common and devastating, and party wipes from a single unlucky, ambush encounter are frequent. As RPG Site’s review starkly notes, “every battle has the chance to be tense, and every battle is likely to defeat you if you don’t prepare properly.”

3. Exploration, Traps, and the Infamous Map Mechanic:

This is the game’s most divisive and defining feature. Dungeons are vast, maze-like, multi-level complexes filled with hidden doors, teleport traps, sliding ice floors, wind tunnels, and underwater sections requiring breath management. The auto-map is non-existent. Instead, players use consumable “Magic Map” items. Each map item reveals the current floor’s layout once, then disappears. As RPG Site’s reviewer states, this “can easily be a deal-breaker.” Managing inventory for these maps—separating precious slots from healing items and equipment—becomes a core, frustrating mini-game. It is a pure test of spatial memory and patience. The design intent is to force players to learn dungeons organically, but for many, it feels like an arbitrary resource tax that stifles exploration rather than enhances it. The only mitigation is teleportation magic, learned later, or resorting to online maps or game file mods.

4. Permadeath and Resource Scarcity:

True to its lineage, Gothic features a harsh permadeath system. A character reduced to 0 HP becomes a “corpse” that must be manually retrieved and dragged to a temple. Resurrection spells (from a Cleric) or temple services have a success rate tied to Vitality (VIT). Failure turns the body to ash; a second failure means permanent death. This creates agonizing decisions: do you risk a deep dungeon dive with a weak revival spell, or retreat to town? Inventory is tight (~20 slots per character, with equipped gear consuming slots), forcing ruthless prioritization between weapons, armor, healing items, and those precious maps. The game’s 50+ hour length is a direct product of this grind-heavy, retreat-and-requeue loop.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Gothic Ambiance on a Budget

The world of Ishmag is less a fully-realized continent and more a series of themed dungeon strata connected by a hub town. The art style, particularly in the PC port, features the series’ signature absurdly high-quality 2D monster and item sprites contrasted with rudimentary 3D environments. The 400+ monster types are the game’s visual triumph—creatures are surreal, grotesque, and dripping with personality, from slimes to cosmic horrors. The “gothic” theme manifests in dungeon architecture (cathedrals, crypts, ritual chambers) and a color palette leaning towards dark blues, purples, and grays.

Sound design is functional. The music, composed by Studio Coil (with series veterans Hitoshi Sakimoto and Masaharu Iwata credited on Wikipedia for the series), is serviceable but unmemorable, often looping without dynamic change. Sound effects are basic—swings, hits, spell casts—and can become grating during long grind sessions. The lack of voice acting beyond occasional grunts reinforces the old-school feel but also contributes to a sense of isolation. The atmosphere is built through environmental cues, monster design, and the sheer tension of first-person navigation, not through cinematic presentation. The PC port’s higher resolution makes the 3D environments clearer but does little to mask their simple geometry, a conscious trade-off for performance on the original PSP hardware.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Classic Defined by Its Flaws

Reception was predictably split along the lines of “traditionalist” versus “modern” expectations.

Critical Reception: Aggregate scores sit around 70%. RPG Site (80%) praised its uncompromising niche fulfillment: “If you are the type of person who relishes in challenging themselves… you can’t do much better than this.” Digitally Downloaded (60%) was more measured, acknowledging Ghostlight’s localization effort but calling it a “B-grade” experience with faults. The core praise centered on its unwavering commitment to classic DRPG mechanics and depth of content. The core criticisms were its brutal difficulty, the “archaic” single-use map system, dated graphics, and lack of tutorials.

Series Legacy and Evolution: The Elminage series occupies a unique space as arguably Japan’s most faithful successor to Wizardry. Its reputation in Japan was stellar for the first two entries (top ranks on mk2.net). Gothic’s mixed reception, coupled with the series producer’s departure, marked a turning point. The Wikipedia entry explicitly states that fans felt Gothic “denied” the series’ world-view due to its narrative disconnect. The last main-series entry was Gothic (with a 3DS remix in 2013). Subsequent series activity has been limited to ports (like the well-received Original on PC/3DS) and an upcoming Switch port. The fan community, however, is dedicated. Mods for the PC version (documented on the Fandom wiki) primarily address quality-of-life issues like clearer map visuals. Fan translation patches have been crucial for unlocalized entries like Elminage II and III.

Influence: Elminage: Gothic did not redefine the DRPG genre but served as a stark, uncompromising benchmark. In an era where even classic-inspired DRPGs like Etrian Odyssey introduced mapping mechanics and gentler progression, Gothic stood as a “turn-based Dark Souls” (per RPGWatch), rewarding only the most patient and obsessive. Its influence is less in mechanics borrowed by others and more in its role as a touchstone for purists, a game that proves the “hardcore” DRPG formula remains viable, if deeply niche. Its localization by Ghostlight also highlighted a viable path for bringing obscure, mechanically complex Japanese titles to a Western audience, midriff and all.

Conclusion: A Flawed Monument to a Bygone Era

Elminage: Gothic is not merely a game; it is a deliberate artifact. It succeeds in its singular goal: to replicate the punishing, cerebral, and rewarding experience of early Wizardry with a distinct gothic flair. Its strengths—unparalleled class freedom, monstrous creativity, and a systemic depth that demands true strategic mastery—are inextricably linked to its weaknesses: the punitive map mechanic, the relentless grind, the near-total lack of player convenience, and a plot so thin it’s almost invisible.

Its place in video game history is that of a specialist’s masterpiece. It is a vital preservation of a design philosophy that has largely faded: the belief that player skill, manifested in preparation and deduction, should be the primary hurdle, not artificial difficulty spikes or degraded statistics. For the player who yearns for the tension of losing a beloved, meticulously-built character to a single trap or ambush, and who finds joy in slowly unraveling a vast, deadly maze with nothing but a dwindling stack of paper maps and a party of six fragile lives, Elminage: Gothic is indispensable.

For everyone else, it is a fascinating, frustrating museum piece—a 50-hour testament to an era of game design that respected the player’s time only after they had proven their absolute dedication. Its legacy is assured not in sales or widespread acclaim, but in its unwavering, brutal fidelity to a lost art. It is a game that asks, “Are you really ready to crawl through these dungeons?” and then happily punishes you for even suggesting you might be.