- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: 1C Company, Blackstar Interactive GmbH, FIP Publishing GmbH, Oxygen Interactive, Snowball.ru, Strategy First, Inc.

- Developer: Infinite-X, ZUXXEZ Entertainment AG

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Campaigns, Map editor, Missions, Real-time strategy, Unit customization

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 67/100

Description

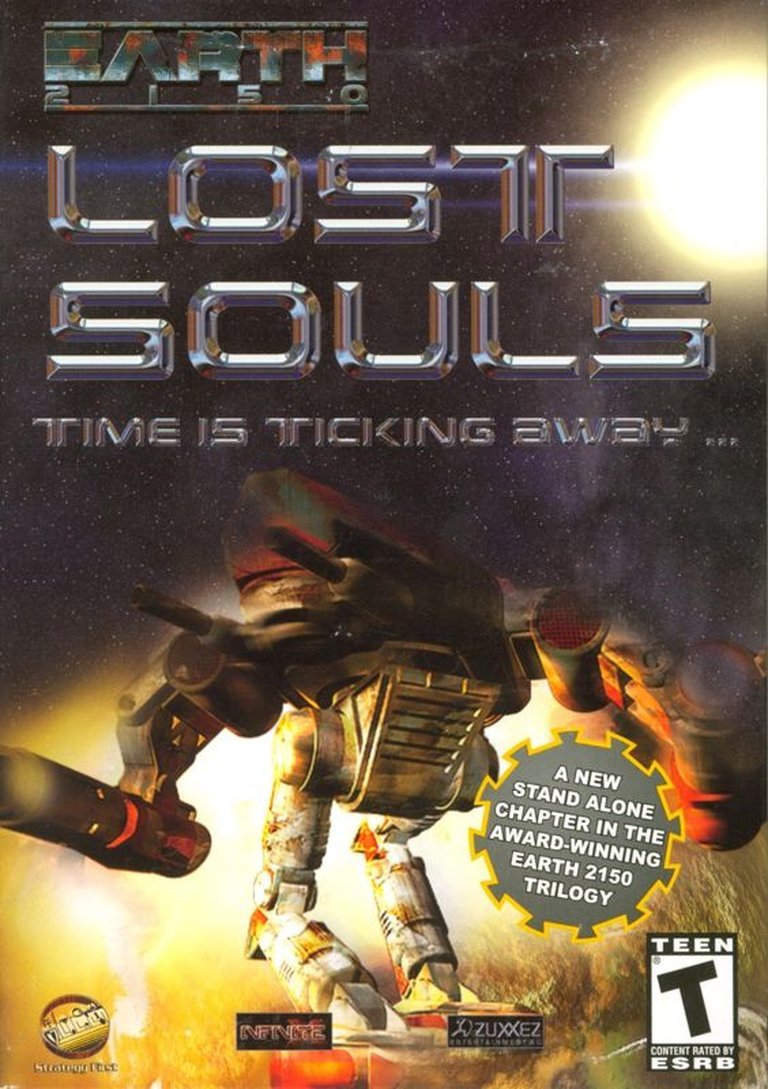

Earth 2150: Lost Souls is a standalone expansion set in a sci-fi futuristic Earth of 2150, where scientists predict an imminent cosmic catastrophe, shattering alliances and igniting a final, desperate war among ‘lost souls.’ Players dive into real-time strategy with three new campaigns totaling 30 missions, featuring deep unit customization, challenging missions, and robust multiplayer options including LAN, Internet, and a map editor for endless tactical combat.

Gameplay Videos

Earth 2150: Lost Souls Patches & Updates

Earth 2150: Lost Souls Mods

Earth 2150: Lost Souls Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (67/100): Die-hard fans will find a lot to like, but most others consider it a rehash.

ign.com : It’s the end of the world as we know it, and I feel fine.

Earth 2150: Lost Souls Cheats & Codes

PC

Press Enter during gameplay to open the console. For most cheats, first enter ‘Cheater 1’ to enable cheat mode, then enter the cheat code. The ‘I_wanna_cheat’ code can be entered directly without enabling cheat mode.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| I_wanna_cheat | Upside down screen |

| Cheater 1 | Enable cheat mode |

| Cheater 0 | Disable cheat mode |

| Tromaville | Damage all visible enemies |

| gohome! | Destroy selected building |

| smash | Destroys everything in sight |

| judgementday | Kill on visible enemies |

| hide | Enable fog of war |

| moonlight | Disable fog of war |

| hereyouare! | Show all enemies |

| mybrainisfaster 1 | Faster research |

| Sciencefornothing | Free research |

| nobelprize | Research everything |

| moneyfornothing # | Free money (enter number) |

| byebye | Instant loss |

| limit_up # | Limit goes up # of levels (enter number) |

| Shower | Meteor shower |

| hotground | Plant mines |

| beautifulmoon 1 | Show full map |

Earth 2150: Lost Souls: The Curious Endpoint of a Pioneering RTS Trilogy

Introduction: A War of Leftovers

In the grand, often blinkered narrative of real-time strategy (RTS) evolution, the Earth series occupies a fascinating, if underappreciated, niche. Developed by Poland’s Reality Pump Studios (later ZUXXEZ Entertainment AG) and published by the perennial TopWare Interactive, the trilogy—Earth 2140, Earth 2150, and its expansions—championed a brutally logical, 3D-battleground philosophy at a time when the genre was being reshaped by the lightning kinetics of StarCraft and the historical breadth of Age of Empires II. Earth 2150: Lost Souls, arriving in late 2001 in Germany and in 2002 internationally, serves as the trilogy’s coda. It is not a evolution, but an intensification—a最后 stand (literally and figuratively) that tightens the series’ unique mechanical screws while exposing the creative exhaustion of its premise. This review argues that Lost Souls is a game of profound contradictions: a technically adept, mechanically deep RTS that is simultaneously a creatively bereft expansion in all but name, a title that offers the series’ most challenging and granular tactical experience but at the cost of the atmospheric urgency and structural innovation that once defined it. It is the definitive, if flawed, last stand of a distinct RTS lineage.

Development History & Context: The Polish Powerhouse and the Declining Star

The Earth series was the flagship of Reality Pump, a studio born from the ashes of Poland’s early post-communist game development scene. Their ambition was colossal: to create a fully 3D RTS with deformable terrain, persistent unit experience, and a global, apocalyptic narrative. The original Earth 2150 (2000) was a technical marvel for its time, running on the proprietary “Reality Pump Engine” and pushing 3D acceleration in a genre still dominated by 2D sprites. Its success spawned The Moon Project (2000), which introduced lunar warfare and refined the core loop.

Lost Souls was developed by Infinite-X and ZUXXEZ Entertainment AG (the rebranded Reality Pump), with production helmed by figures like Adam Phillips and Susannah Skerl. It was conceived as a standalone expansion—the “third installment”—but the source material overwhelmingly indicates it was built on the existing Moon Project codebase with significant asset reuse. The technological context is crucial: by 2001-2002, the RTS landscape was bifurcating. One path led toward hyper-accessible, hero-centric, streamlined design (Warcraft III, Battle Realms). The other led toward massive-scale, simulation-heavy warfare (Total Annihilation’s spiritual successors). Lost Souls Double-downed on the latter, but without the fresh presentation or systemic innovation to justify a full sequel. Its release was also overshadowed by titans like Command & Conquer: Tiberian Sun and Age of Empires II, as noted in German sales reports, and in the US, it failed to chart, selling a mere ~23,000 units initially. This commercial underperformance was not due to complexity alone, but to a market rapidly moving on from its specific brand of “old-school” strategizing.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Politics of Abandonment

The premise of Lost Souls is inherently dramatic: on December 7th, 2150, Earth is doomed. The three factions—the United Civilized States (UCS), the Eurasian Dynasty (ED), and the Lunar Corporation (LC)—have launched their primary evacuation fleets to Mars. Those left behind, the “Lost Souls,” are the dregs of society, the military remnants, and the politically disfavored. This sets up a potent thematic triad: betrayal, survival, and pyrrhic revenge.

The narrative is delivered through three chronological, faction-specific campaigns, a significant structural upgrade from the more disjointed Moon Project.

-

ED Campaign – The Czar’s Purge: Players follow General Fedorov, a loyal instrument of the paranoid Czar Vladimir II. The campaign is a masterclass in political cynicism. Missions begin as resource grabs for the shuttle program but morph into internal purges. The central tragedy is the revelation that the Czar’s shuttles hold only one million seats—a fraction of the ED population. Fedorov and his ally General Ivanov are marked for execution as potential rivals. Their rebellion, culminating in the failed assault on the Chinese launch silos (a mission famously with a fake, impossible timer), is a desperate act of self-preservation that shifts into a quest to hijack the LC’s alternative escape technology (the space teleporter). The theme here is decay from within; the ED’s fascist, Mongol-inspired hierarchy cannibalizes itself.

-

LC Campaign – The Last Hope: The LC, pacifist lunar technocrats, are left with their primary research complex in Poland and a “recruit” (the player) thrust into command. Their plot is one of scientific desperation. Their escape plan, the space teleporter, is broken. The solution? Steal the teleportation data from their former UCS allies, now led by the traitorous General Marcus Grodin (initially mistaken for rebels). This necessitates a covert, globe-trotting mission: infiltrate America from Portugal, steal from a Chinese lab, and ally with actual UCS rebels to deactivate the UCS Central AI, GOLAN. The campaign’s irony is thick: the most technologically advanced, peace-loving faction must resort to theft, deception, and alliance with the very “rebels” they were hunting to achieve salvation. The LC’s campaign is a study in moral compromise for survival.

-

UCS Campaign – The Grodin Gambit: This is the most narratively complex campaign, following Marcus Grodin and his “rebel” UCS forces. Framed as terrorists by the LC, Grodin’s true goal is to prove his innocence and expose that GOLAN’s attacks were ordered by the eliminated High Command to ensure the Lost Souls remained on Earth. Players must evade LC and ED forces, raid abandoned bases, and gather evidence. The campaign’s climax—a three-way alliance against GOLAN in Belarus and Poland—reveals the ultimate conspiracy: all three ruling councils (Czar, LC Celestial Council, UCS High Command) colluded to strand the Lost Souls. The final lines, where the victorious but forsaken armies enter the teleporter “knowing it could very well malfunction,” are a bleak, existential capper. Victory is not triumph, but a gamble with annihilation.

Collectively, the narrative elevates Lost Souls from a simple “last stand” scenario to a grim political thriller of the apocalypse. Themes of class betrayal (the elite escaping), ideological collapse (ED’s paranoia, LC’s pacifism shattered, UCS’s AI governance failing), and the meaning of legacy permeate every mission briefing. It’s a sophisticated, if dour, story that far exceeds the typical RTS excuse plot.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Depth at a Cost

Lost Souls is functionally identical to Earth 2150 and The Moon Project in its core systems, but with critical, punishing adjustments that define its identity.

The Canonical Loop: Players select a faction, embark on a campaign mission with specific objectives (destroy all enemies, capture a base, defend a location), and must manage three core resources: Credits (money), Energy (for LC), and Ammunition. Base building, tech research, and unit production follow. The persistent “Main Base” from the first game is gone, replaced by a straightforward resource pool per mission—a simplification that removes the strategic layer of evacuation quota management but makes each mission a self-contained, brutal war of attrition.

1. Unit Customization – The Heart of the Matter: This remains the series’ signature innovation. Players don’t just build pre-fab units; they design them. From a chosen chassis (light, medium, heavy for land/sea/air), you select a primary weapon, secondary (or multiple) weapons, and equipment (shields, stealth generators, repair modules). You can even script basic AI behaviors (“Hold Area,” “Retreat at 50% HP”). This creates a staggering number of potential unit classes. A slow, heavy ED tank can be fitted with a long-range artillery piece and a shield, becoming a mobile bunker. A fragile LC scout can be armed with machine guns and a stealth generator for hit-and-run raids. This system encourages profound tactical thinking: analyzing the enemy’s composition (ballistic vs. energy weapons, shield usage) and counter-designing your forces is not optional, it is mandatory.

2. Ammunition & Logistics – The Draining Sieve: This is Lost Souls’ most defining and divisive mechanic. Every weapon, except for regenerating energy-based tools, has strictly limited ammo. Machine guns, cannons, rockets—all deplete. Resupply is handled by dedicated “ammo carrier” units that must physically connect to depleted units (ground/naval) or by landing at an ammo depot (air). This creates a relentless logistical chain. A massive armored push can grind to a halt as your frontline tanks run dry and your carriers are shot down. It forces a rhythm of combat: assault, retreat/resupply, reassess. It is brilliantly realistic and utterly exhausting. As one critic noted, it makes the game “more complex than StarCraft.”

3. AI & Difficulty – The Relentless Onslaught: The AI in Lost Souls is infamous. It no longer focuses on harassment; it launches constant, massive ground and air assaults from its starting position—a “fully built and heavily fortified base,” even on Medium difficulty. The AI is also more aggressive in seeking out and destroying your ammo carriers and supply lines. The effective meta, as many players and critics discovered, is a war of attrition: fortify your position, whittle down the AI’s endless waves until it exhausts its local resources, then counter-attack. This makes many missions feel less like dynamic battles and more like sieges against a fountain of units. The difficulty is punishing, with a steep learning curve exacerbated by, as IGN’s review starkly states, “the written documentation for this game really sucks.”

4. The Missing Innovations & Flaws: For veterans, the sense of déjà vu is palpable. There are no new units, no new factions, no graphical overhaul. The tech tree is identical. The campaign structure is more coherent, but objectives are often simplistic (“Kill everything”). The removal of the global evacuation timer from the first game drains the apocalyptic tension, replacing it with mission-specific artificial constraints. The interface, as German critics (PC Games, PC Action) consistently noted, remains “unergonomic” with cramped build menus. Pathfinding for large formations is still problematic, leading to units “driving past targets” or getting stuck. These are not new flaws, but inherited ones that feel less forgivable in a standalone release.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Dying World, Rendered in Blocky 3D

Visually, Lost Souls is a game in arrested development. The engine is the same from 2000. When zoomed out, the 3D landscapes—spanning deserts, snowfields, and ruined cities like San Francisco or Vienna—are serviceable and functional for gameplay. The diagonal-down isometric perspective with a free camera allows for excellent tactical overview.

Where the art sings is in its atmospheric details. The dynamic day/night cycle is tactically relevant: units have lights that can be switched off for stealth during night assaults. Weather effects—blizzards, rainstorms—are not just cosmetic; they obscure vision, making them tools for ambush. The silence of a night raid, broken only by the whir of LC anti-grav engines, is palpable. Explosions and weapon effects (laser beams, plasma cannons, rocketing debris) are crisp and impactful, a consistent strength. The blocky unit models and texture pop-in are evident, but the overall visual cohesion—the sense of a war-torn, dying Earth—is maintained.

The sound design is a similar mix of effective and dated. The dynamic soundtrack, identical to its predecessors, shifts effectively from tense ambient tracks to driving techno during combat. The sound effects for weapons, construction, and explosions are weighty and satisfying. The fatal flaw remains the voice acting. As IGN summarized, it is “cheesy,” with the UCS’s emotionless robotic drones, the ED’s heavily accented gravel, and the LC’s over-enthusiastic matriarchs all coming across as unintentionally comical. This undermines the serious narrative at every turn.

Reception & Legacy: A Divided Legacy on the Battlefield

Lost Souls received a Metacritic score of 67 (based on 11 critic reviews at the time) and a MobyGames average of 70% from 17 critics. Reviews were,and remain,deeply polarized, reflecting its dual nature.

The Positive View (Eurogamer 80%, Yahoo! 80%, GameSpot 78%): Critics in this camp celebrated its uncompromising depth. It was hailed as “one of the most detailed, old-school RTS titles since StarCraft” (Eurogamer). They praised the relentless tactical challenge, the genius of the ammo/resupply system forcing genuine logistics, the freedom of unit customization, and the strength of its three-part narrative. For hardcore strategists, its “slow” pace and complexity were virtues, offering a chess-like cerebral experience absent from faster-paced contemporaries.

The Critical View (Adrenaline Vault 40%, CGW 40%, PC Zone 70%): This camp saw it as a glorified mission pack. The refrain was universal: “If you own The Moon Project, there is almost nothing new here.” The lack of graphical or systemic innovation was a cardinal sin in a rapidly advancing genre. PC Gamer UK called it “a staid standalone mission pack for a title that deserves so very much more.” The punishing AI and opaque interface were framed as accessibility failures, not challenges. Adrenaline Vault’s scathing review captured the sentiment: “Fans of the series deserve the same content for far less money in the form of a true expansion pack.”

This critical split mirrors the player community divide IGN observed. The online multiplayer scene largely remained with The Moon Project, seeing Lost Souls as a lateral move. Yet, a dedicated cult appreciated its singular focus on attrition warfare and unit design.

Legacy: The legacy of Lost Souls is as the final polished expression of Reality Pump’s RTS vision. It did not influence the mainstream genre trajectory. Instead, its lineage is niche: its unit customization and ammo mechanics can be seen as precursors to the deeper logistics of games like Company of Heroes (supply lines) or the unit design pillars of Sins of a Solar Empire. Its greatest impact may be historical—it represents the end of an era where PC RTS developers could pursue complex, “unfriendly” systemic depth without the pressure of mass-market accessibility. The series would limp on with the poorly received Earth 2160 (2005) before vanishing into obscurity, only to be resurrected decades later by a dedicated fan community preserving its legacy.

Conclusion: The Last, Lost Stand

Earth 2150: Lost Souls is not a great game by modern standards. Its interface is clunky, its AI brutally unfair, its presentation dated, and its lack of innovation blatant. Yet, to dismiss it is to overlook a remarkable, if flawed, exercise in tactical design. It is a game that asks players to think in terms of logistics, counters, and persistent force composition in a way few RTSes ever have. Its narrative of desperate, betrayed remnants fighting for a illusion of salvation is one of the most politically astute and thematically cohesive in the genre.

Its place in history is secure as the definitive, if tragic, endpoint of a pioneering trilogy. It is the moment the Earth series’ technical ambition and narrative hunger fully consumed itself, leaving a mechanically rigorous but creatively barren landscape. It is a game for the persevering, the historian, and the strategist who finds beauty in the granular dance of supply and demand, shield and shell. It is the final, bitter campaign of a lost cause—the Lost Souls themselves—and a fitting, if imperfect, monument to a bold, buried chapter in RTS history. Verdict: A flawed masterpiece of depth, and the poignant, final battle of a forgotten war.