- Release Year: 1995

- Platforms: Windows

- Developer: Didier Frick

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Logic puzzle, Tile placement, Turn-based

Description

T4 is a 1995 shareware logic game for Windows, developed by Didier Frick, that pits two players against each other in a turn-based tile-placement contest. Using squares divided into four colored triangular sections (with all 16 unique combinations), players alternately give and place tiles on a board, striving to complete a horizontal, vertical, or diagonal line where one specific triangle color is consistent across every tile in that line, with options for human vs. human, human vs. computer, or computer vs. computer matches featuring three skill levels.

T4 Reviews & Reception

theotherside.timsbrannan.com : the task resolution is not terrible, but there are better ones.

T4 Cheats & Codes

PlayStation

Enter button sequences at the password screen; advanced attack cheats are entered during gameplay.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| Left, Right, Up, Up | Freeze |

| Up, Up, Down, Down | Hyperspace |

| Down, Down, Up, Up | Invisibility |

| Up, Up, Left | Jump |

| Up, Down, Up, Down, Up | Massive Attack |

| Right, Left, Down, Down | Rear Attack |

| Left, Right, Down, Down | Rear freeze |

| Up, Down, Up, Down, Down | Rear Massive Attack |

| Up, Up, Right | Shield |

| Down, Start, R1, Up, Start | All weapons with 99 ammo |

| Start, Right, R1, L1, R1 | Get 99 massive attacks |

| Circle, Left, Triangle, R1, Circle | Get 99 Freeze Missiles |

| Down, R1, Start, Left, Triangle | Homing weapons become better seekers |

| Right, L1, Right, Left, L1 | Stronger Power Missiles |

| Down, R1, Down, Down, Start | No health in all modes |

| Circle, Start, Left, L1, Start | No pick-ups |

| Right, Triangle, Right, Triangle, L1 | CPU cars target players |

| R1, Right, Left, R1, Up | All power-ups are Homing Missiles |

| Right, Left, R1, Right, Circle | All power-ups are Napalms |

| Down, Down, Circle, L1, Left | All power-ups are Power Missiles |

| Up, Right, Down, L1, Triangle | All power-ups are Remote Bombs |

| Circle, Up, Down, Up, Up | Able to select 0 enemies in Deathmatch |

| L1, Left, Right, Circle, Right | CPU cars ignore health power-ups |

| R1, L1, Down, Start, Down | Extra fast weapons |

| Down, Left, L1, Left, Right | God mode |

| Triangle, Down, Triangle, Circle, Triangle | No health in Deathmatch mode |

| Down, R1, Down, Start, Circle | No health in Tournament or Deathmatch mode |

| Circle, Start, Left, L1, Start | No health or weapon power-ups |

| Down, Down, Right, Right, Down | One CPU ally VS two human opponents |

| Up, Start, Circle, R1, Left | Powerful special weapons |

| Triangle, L1, Down, Triangle, Up | Unlimited special weapons |

| Down, Triangle, Down, L1, R1 | Very little traction |

| Up, Right, L1, L1, Down | Demo attraction movie starts much quicker |

| Right, Triangle, Right, Right, Left | Start at Neon City |

| Start, Start, Down, Circle, L1 | Start at Road Rage |

| L1, Right, Left, Left, L1 | Start at Bedroom |

| Circle, L1, Start, L1, Start | Start at Amazonia 3000 B.C. |

| Start, Left, Up, Start, Circle | Start at The Oil Rig |

| Start, R1, Left, R1, R1 | Start at Minion’s Maze |

| Circle, Left, Down, R1, L1 | Start at The Carnival |

| Triangle, Right, Up, Left, L1 | All characters & levels |

| Down, R1, Right, R1, L1 | Unlock Crusher |

| Start, Triangle, Right, L1, Start | Unlock Moon Buggy |

| Circle, Triangle, Start, Circle, Left | Unlock Super Thumper |

| Up, Down, Left, Start, Right | Unlock RC Car |

| Up, Right, Down, Up, L1 | Unlock Super Axel |

| Left, Circle, Triangle, Right, Down | Unlock Super Auger |

| Right, L1, Start, Circle, Start | Unlock Super Slamm |

| Triangle, L1, L1, Left, Up | Unlock Minion |

| Start, R1, Right, Right, Left | Unlock Sweet Tooth |

| Left, Triangle, Right, Right, Left | Start at Neon City |

| Triangle, L1, Down, Triangle, Up | Faster health regeneration |

T4: A Tale of Two Games – Deconstructing an Obscure Title and Its Better-Known Namesake

Introduction: The Shadow of a Name

In the vast digital catacombs of MobyGames and the passionate fora of tabletop history, the designation “T4” hangs like a enigmatic label, affixed to at least two radically different gaming artifacts from the mid-1990s. One is a nearly forgotten, minimalist shareware logic puzzle for Windows. The other is a notorious, troubled, yet conceptually ambitious fourth edition of the seminal tabletop science-fiction RPG Traveller. This review will treat both entities with the gravity they individually deserve, unraveling why a simple string of characters can bifurcate into such divergent experiences. My thesis is this: the obscurity of the 1995 PC game T4 is a quiet testament to the cul-de-sacs of early shareware logic design, while the infamy of the 1996 Marc Miller’s Traveller (T4) reveals a pivotal, painful moment in RPG history—a compromised bridge between eras whose flawed execution ultimately preserved a core classicist vision for a dedicated few.

Development History & Context: Two Studios, Two Trajectories

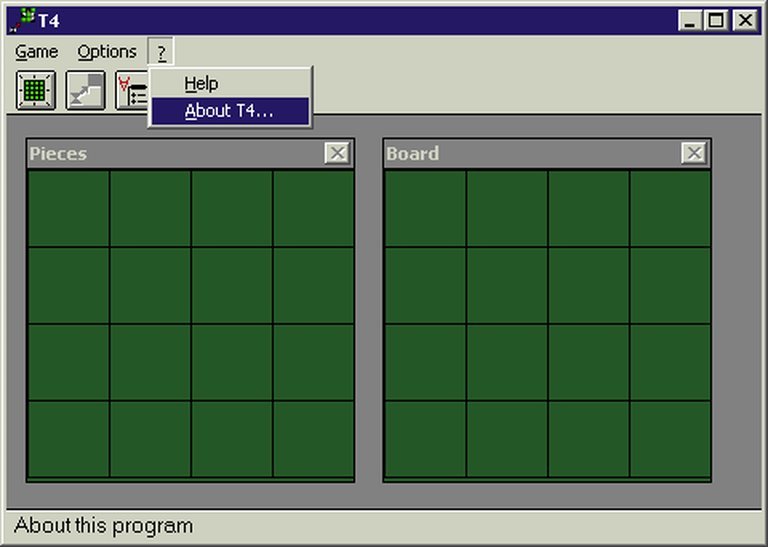

1. The 1995 T4 (Didier Frick)

Developed by a single auteur, Didier Frick, this title embodies the solo-shareware boom of the early Windows era. Released in December 1995, it arrived as the PC gaming landscape was fracturing between 3D accelerators (the Voodoo Graphics card launched that year) and the last gasps of 2D shareware. Its context is not within a genre evolution but within a distribution model: the developer-hosted website and the shareware disk compilation. There is no known studio history, no interviews, no design post-mortems. It exists as a ghost in the machine of MobyGames—collected by only two users. Its technological constraint was the Windows 95 API and the limitations of GDI for tile rendering, placing it aesthetically in the same bin as Minesweeper and WinTile.

2. The 1996 Marc Miller’s Traveller (Imperium Games)

The narrative here is one of corporate collapse and rebirth. Following the dissolution of Game Designers’ Workshop (GDW) in February 1996, the rights to Traveller reverted to its co-creator, Marc W. Miller. He licensed the property to Imperium Games, a company founded by the prolific but controversial Ken Whitman, financed by Courtney Solomon (later of the infamous Dungeons & Dragons film). The team poached key GDW alumni—Lester Smith, Timothy B. Brown—with the stated goal of creating a “Classic Traveller 2.0” set in Milieu 0, the dawn of the Third Imperium, some 1,100 years before the classic “1105” setting.

The development was reportedly frantic—the core rulebook was written in four months. This breakneck schedule, combined with Whitman’s reputedly chaotic management and a lack of professional editing, resulted in a product famously riddled with typos, layout errors, and mechanical contradictions, necessitating over 30 pages of consolidated errata. The technological “constraint” was ironic: this was a print product in an era shifting to desktop publishing, but its internal logic was fractured. The gaming landscape of 1996 was dominated by Magic: The Gathering‘s explosion, the rise of Vampire: The Masquerade, and the impending 3rd edition of Dungeons & Dragons. T4 was a deliberate nostalgic reboot in a market racing forward.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The 1995 T4: There is no narrative. The “story” is the abstract logic of the game itself. The thematic core is pure mathematical conflict: a duel of symmetrical information, where the only narrative is the emergent tension of forcing your opponent to place a tile that completes a monochromatic line (either white or black triangles) in a horizontal, vertical, or diagonal row. It is a game of spatial jiu-jitsu, of offering poisoned chalices. The theme is inevitability and constraint—each move tightens the noose on the board, a silent counting-down to the inescapable completion.

The 1996 Marc Miller’s Traveller: This is where T4 becomes historically significant. Its narrative theme is rebirth and rediscovery. Set in Milieu 0, the setting is not a decaying empire but a fledgling one, the Sylean Federation expanding from Core Sector to reclaim worlds lost in the Long Night. The thematic heart is the same as Classic Traveller: solo adventurers on the fringe, making their fortune. The rulebook’s default adventure, “Exit Visa,” is a classic Traveller scenario—ancient alien mystery, bureaucratic intrigue. The library data, painstakingly copied from earlier works, reinforces a theme of historical layering. However, this theme is constantly undermined by the game’s own internal chaos. The thematic depth is not in the prose (which is often derivative) but in the meta-narrative of its creation: a desperate attempt to bottle the lightning of 1977’s Little Black Books in a world that had moved on to complex metaplots like MegaTraveller‘s “Reformation Wars.” It is a game about returning to a simpler, more open frontier, published by a company that couldn’t find its own editorial frontier.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The 1995 T4 (Logic Game):

* Core Loop: Asymmetric placement. Player A selects a tile from the pool of 16 possible combinations (4 triangular quadrants, each black/white) and hands it to Player B, who must place it on a growing grid. The act of giving the piece is the critical strategic move. The loop is: Choose tile -> Force opponent -> Opponent places -> Check for winning line.

* Innovation/Flaw: The entire mechanic is the innovation: the compulsion move. It’s a pure exercise in forcing moves, akin to Go but with a shared, finite piece pool. The flaw is its potential for tedious backtracking and the sheer difficulty of visualizing 16-tile combinations and their board-state implications. It lacks scoring depth or progressive goals beyond the single win condition. Its elegance is also its limitation; there is no campaign, no progression, just the infinite, silent duel.

The 1996 Marc Miller’s Traveller (RPG):

* Character Generation: Universally praised as the best in the Traveller line. It’s a rich, multi-stage process (Homeworld, Background, Career, Advanced Education) with more skills and fewer lethal pitfalls than Classic Traveller. The use of “mustering out” benefits and a more forgiving injury system are seen as major improvements.

* Task Resolution: The major point of contention. It uses a “roll under” system on 2d6+modifiers, but with infamous x.5 die modifiers (e.g., +1.5, -2.5). This was an attempt to create fine-grained difficulty gradations but resulted in unwieldy, un-intuitive math. The system was the direct predecessor to T5‘s “toolkit” approach, but for T4, it felt clumsy. The commentary is unanimous: the rules work on paper but feel “weird-ass” and less fun than the clean 2d6 target numbers of Classic or MegaTraveller.

* Combat: Ground combat reintroduced range bands (Point-Blank, Short, Medium, Long, Very Long), a beloved Classic feature missing from MegaTraveller. The damage/penetration model, adapted from Striker and MegaTraveller, is praised for being granular and lethal. However, a critical flaw exists: the character generation system can produce PCs with such high skill levels (especially in combat skills) that they easily “steamroll” the combat challenges presented, a direct result of the powerful chargen and the sometimes vague difficulty scaling in the task system.

* Starship Design: A highlight. The “Fire, Fusion & Steel” chapter is lauded as a robust, character-like ship creation system. The “Naval Architect’s Manual” for interior design is also well-regarded. These sections felt more polished and thoughtfully designed than the core task rules.

* Overall System Synthesis: The fatal flaw is a lack of cohesion. The chargen makes competent, high-skill characters. The task system is fiddly. The combat is lethal but can be trivialized. The result is a game that feels like three separate, partly-finished projects stapled together, lacking the holistic elegance of Classic Traveller or the narrative tools of later editions.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The 1995 T4: Non-existent. The “world” is the monochrome grid of the board. The only “art” is the functional tile graphics. The atmosphere is one of cold, abstract calculation. The sound, if any (shareware often had none), would be the click of the mouse. Its contribution is to create a pure, unadorned cognitive space.

The 1996 Marc Miller’s Traveller:

* Art: This is its saving grace and most celebrated feature. While Traveller historically had “functional” or “descriptive” art, T4 featured stunning work by Larry Elmore and Chris Foss. The color plates, especially Foss’s cover and ship illustrations, are considered among the best in the franchise’s history—epic, pulpy, and visually cohesive. The interior art is similarly high-quality, evoking 70s/80s sci-fi paperback covers. This art created a powerful, aspirational mood that the inconsistent text often failed to match.

* Setting & Atmosphere (Milieu 0): The setting is a unique and compelling “what-if”: the Third Imperium before it was an empire. It’s a period of nation-state level politics (the Sylean Federation), rediscovery, and frontier expansion, more akin to Firefly or The Expanse than the space-opera empires of later Traveller. The sourcebooks like Milieu 0 and Pocket Empires flesh this out with system-neutral political and economic details. The atmosphere is one of potential and grit, not established galactic civilization. However, the rulebook’s reliance on copied Classic Traveller library data (which assumes the year 1105 and the existence of the Imperium) creates a jarring dissonance between the new setting’s lore and the reused reference material, undermining the intended atmosphere.

Reception & Legacy

The 1995 T4: Non-existent in the critical record. It left no footprint. No reviews, no discussions, no influence. It is a perfectly preserved artifact of obscurity, a shareware logic game that failed to find an audience or inspire clones. Its legacy is zero, a silent data point in the history of puzzle games.

The 1996 Marc Miller’s Traveller:

* Launch Reception (1996-98): Terrible. It was dissected in the nascent online community (Usenet, early web forums) for its typos, editorial disasters, and mechanical inconsistencies. The 30 pages of errata became a mandatory supplement. Imperium Games’ reputation was destroyed within a year, and the company folded in 1998. The line is remembered for its high potential and catastrophic execution.

* Evolved Reputation (2000s-Present): A cult classic of the “so-bad-it’s-interesting” or “diamond in the rough” variety. Modern retrospectives (like Timothy Brannan’s detailed blog review) acknowledge:

1. Character Gen & Art: Landmark achievements.

2. Milieu 0: A beloved, unique setting that lives on in fan discussions and was later revisited more competently by other publishers (e.g., GURPS Traveller: Interstellar Wars).

3. Systemic Influence: The task system directly evolved into T5 (the “Big Black Book”), which, while still divisive, was more coherent. Concepts like Pocket Empires (a campaign-scale empire management mini-game) are cited as brilliant, underdeveloped ideas.

4. The “T4” Philosophy: It represented a hardline Classic revivalism that rejected the narrative complexity and metaplot of MegaTraveller and TNE. For purists, it was a necessary corrective, even if flawed.

* Influence: Its direct influence was stifled by its commercial failure. However, its setting, Milieu 0, has had a lasting impact. It provided a clean, pre-Imperial slate that Mongoose Publishing later explored in their Traveller line. Its most lasting legacy is as a cautionary tale about the perils of rushed development and poor editing in a legacy product. It proved that nostalgia and great art alone cannot save a mechanically disjointed core book.

Conclusion: Verdict on a Schizophrenic Title

To speak of “T4” is to speak of two separate games, one a ghost, the other a revenant.

For the 1995 Windows logic game T4: It is a curio. Its design is academically interesting—a pure, forced-placement mechanic—but it is ultimately a dead end. It lacks layers, presentation, or hooks to sustain interest beyond a few sessions. In the history of puzzle games, it is a footnote, a what-if. Verdict: Historically insignificant, mechanically sterile, deservedly obscure.

For the 1996 Marc Miller’s Traveller (T4): This is a tragic landmark. It is the black sheep of a legendary RPG family, born from corporate misfortune and delivered with shocking negligence. Its pages contain the best character generation system the franchise ever saw, breathtaking art, and a genuinely fresh, appealing setting (Milieu 0). Yet these gems are buried under landslides of typos, a schizophrenic task resolution system that fails to synergize with the powerful characters it creates, and a lazy reliance on outdated library data that contradicts its own timeline.

Its place in history is not as a successful product, but as a critical inflection point. It was the last gasp of the original Traveller vision before the property entered a long period of licensing limbo and experimental reboots (GURPS, T20, Hero). It demonstrated that the core appeal of Traveller was its open-ended, “let-you-do-anything” sandbox, best served by simple, robust rules (which T4’s chargen provided) and a evocative setting (which Milieu 0 provided). Everything else—the clumsy dice, the poor editing—was noise.

Therefore, the final verdict is bifurcated: the 1995 T4 is a non-entity. The 1996 T4 is a frustrating, flawed, yet deeply influential failure. It failed as a product but succeeded in crystallizing what a certain segment of the Traveller audience truly wanted: the feel of the 1977 original, updated with 20 years of accumulated design wisdom, wrapped in art that soared. Its spirit, if not its precise rules, would eventually be realized more successfully by Mongoose Publishing’s 2008 Traveller and the Cepheus Engine. T4 remains the painful, beautiful, messy chrysalis from which those later successes would emerge, a testament to the idea that a game’s legacy is sometimes forged not in its perfection, but in the passionate dissection of its profound imperfections.