- Release Year: 2007

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: ValuSoft, Inc.

- Developer: ImaginEngine Corp.

- Genre: Compilation, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Hotseat, LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Board game

Description

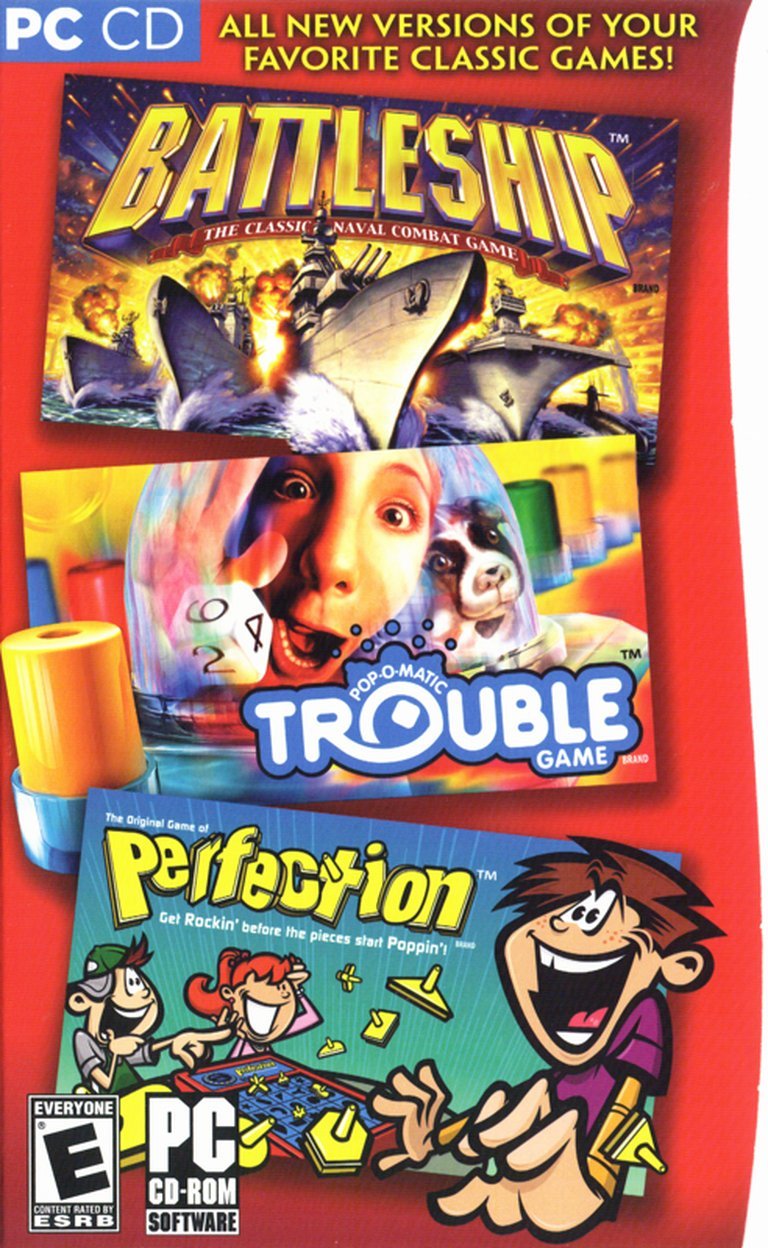

Battleship / Trouble / Perfection Collection is a 2007 Windows compilation that digitally adapts three classic board games: the naval strategy of Battleship, the dice-rolling chaos of Trouble, and the shape-matching frenzy of Perfection. It brings these tabletop experiences to PC with top-down visuals, blending real-time and turn-based elements for a versatile board game collection.

Battleship / Trouble / Perfection Collection: A Shovelware Time Capsule from the Mid-2000s

Introduction: The Triumph of the License, The Death of Ambition

In the landscape of video game history, few artifacts are as telling of a specific economic and cultural moment as the budget-priced, licensed compilation. The Battleship / Trouble / Perfection Collection, released for Windows in August 2007 by the prolific bargain-bin specialist ValuSoft and developed by ImaginEngine Corp., stands as a pristine, unassuming monument to this era. It is not a game that sought to redefine its source material, innovate on digital board game adaptations, or craft a memorable experience. Instead, it is a digital rights-management exercise—a minimalist translation of three iconic Hasbro board games (Battleship, Trouble, and Perfection) into a single, no-frills package. This review will argue that the collection’s primary significance lies not in its gameplay, which is functionally inert, but in its role as a stark exemplar of the “shovelware” phenomenon. It represents the nadir of the licensed adaptation: a product where the mere possession of intellectual property rights superseded any discernible creative or technical effort, destined for immediate obscurity and eventual abandonware status.

Development History & Context: The ValuSoft Assembly Line

To understand the Battleship / Trouble / Perfection Collection, one must first understand its creator and publisher. ImaginEngine Corp. was not a household name but a studio operating within the sphere of value-oriented publishers, often tasked with rapid, low-budget conversions of casual and family-friendly properties. Their portfolio suggests a focus on straightforward, often licensed, titles requiring minimal original asset creation or game design innovation.

Their partner, ValuSoft, Inc., was the archetypal late-1990s/2000s budget publisher. Their business model was simple: acquire cheaply-licensed properties (often from defunct or uninterested IP holders), pair them with a similarly low-cost developer like ImaginEngine, and distribute them via big-box retailers and later, digital storefronts, at a price point attractive to impulse buyers and the uninformed. The game’s August 2007 release date places it in a peculiar transition period. The digital distribution revolution was beginning (Steam was gaining traction), but the boxed-CD-ROM market for casual, family “computer games” still lingered in the aisles of Walmart and Best Buy. This collection was very much a product of that dying shelf-space economy.

Technologically, the constraints were severe. The use of Bink Video middleware (a common, inexpensive tool for playing cutscenes) hints at the inclusion of likely cheaply produced tutorial or intro videos. The CD-ROM media type was already archaic for a simple board game compilation in 2007, a cost-saving measure over digital download. The top-down perspective was a non-negotiable given the source material. The game’s specs—supporting 1-4 players via LAN or split-screen—were standard for the era’s multiplayer expectations but required no server infrastructure, again reflecting a lean budget. There is no evidence of any creative “vision” beyond a directive to replicate three board games with as few polygons and lines of code as possible.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Void of the Digital Tabletop

Here, we must confront a fundamental absence. The Battleship / Trouble / Perfection Collection possesses no narrative, no characters, and no dialogue. This is not a failing but a condition of its form. The “story” is the rules of each game, inherited entirely from their physical counterparts. Therefore, any thematic analysis must descend from the board games themselves, examining what their digital implementation preserves or distorts.

- Battleship is a thematic exercise in military abstraction and probabilistic deduction. It reduces naval warfare to a grid of hidden coordinates, transforming strategic fleet command into a game of statistical guesswork and psychological patterning (“He’s clustering his ships in the corner!”). The digital version theoretically preserves this cold, analytical mindset, but loses the tactile satisfaction of physically announcing “You sunk my battleship!”

- Trouble is pure, unadulterated thematic chaos controlled by a pop-o-matic dome. Its theme is the frantic, luck-driven race of a “Trouble” peg around a board. The core experience is the tactile, auditory thrill of pressing the dome and hearing the plastic clack as the die is popped. The digital translation, by necessity, replaces this physicalFeedback with a sound effect and visual animation, potentially neutering the game’s primary sensory hook and reducing it to a random-number-generator simulator with a jaunty, inevitable tune.

- Perfection is a theme of tautological pressure. The name itself is the theme: the player must fit a set of irregularly shaped pieces into a correspondingly irregular board before the timer ticks them all out. It’s a test of spatial reasoning under duress, with the “theme” being the abstract concept of “perfection” itself. The digital version replicates the anxiety of the countdown timer but again severs the crucial, satisfying physical act of snapping a piece into its precise slot.

The collection, therefore, has no subtext, only a meta-theme of digitized nostalgia. It exists to allow a player to remember playing these games, but it offers nothing new to feel about them. The underlying themes of luck vs. strategy, competition vs. cooperation, and the universal anxiety of time pressure are all present in potentia, but the digital format often dilutes them, replacing physical engagement with passive observation.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Study in Subtraction

Deconstructing the “core gameplay loops” of this collection is an exercise in describing the rules of three separate board games, as the digital implementation adds virtually nothing.

- Battleship: The loop is classic: place your fleet (carrier, battleship, etc.) on a hidden grid, then take turns calling out coordinates (“B-7”) on your opponent’s grid, receiving “Hit” or “Miss” feedback. Victory comes from sinking all opponent ships. The digital version must handle grid management, ship placement rules, and hit detection. However, the innovative or flawed systems are almost certainly in the failure to adapt. A proper digital adaptation could offer tutorials, statistical tracking, or novel AI opponents of varying difficulty. This collection, given its pedigree, almost certainly features a bare-minimum, rudimentary AI (“place ships randomly; call coordinates randomly”) with no difficulty settings, no replay tracking, and no penalty for poor play. The UI is likely a static grid with basic color-coded hits and misses.

- Trouble: The loop is roll-and-move with the central pop-o-matic mechanic. Players take turns, popping the die and moving their peg the indicated number of spaces, with special rules for landing on opponents. The digital version’s critical challenge is replicating the pop-o-matic interaction. This is typically done by clicking a digital representation of the dome. The flaw is inherent: the physical act is the game’s soul; clicking a button is a hollow echo. There is no tension, no tactile randomness. The rest is automated movement.

- Perfection: The loop is a race against time. The player must fit all shapes into the board before the timer (usually 60-90 seconds) runs out and pops all pieces out. The digital version requires precise mouse control for shape manipulation and a reliable timer. The potential flaw here is in control responsiveness and timer “fairness.” A poorly programmed version might have unresponsive drag-and-drop or a timer that feels artificially sped up to compensate for faster digital piece manipulation.

Across all three, the “systems” are barely present. There is no character progression—the games are identical from session to session. The UI is likely a static, unadorned representation of the board game layout, with buttons for “New Game,” “Quit,” and perhaps a minimal options menu for sound toggles. The only “innovation” is the container—launching any of the three games from a single, simple menu—which is not an innovation but a standard compilation trope. The entire package is a testament to functional minimalism, where the only goal is to not incorrectly implement the rules, not to enhance them.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetic of the Generic

The setting for all three games is, by definition, abstract. Battleship is the high seas, Trouble is a whimsical race-track, and Perfection is a blank void. The digital collection’s art direction does not build worlds; it scans them.

- Visual Direction: One can confidently infer the aesthetic from the developer’s reputation and the era: low-polygon, brightly colored, static assets. The board for Perfection will be a flat, textured plane. The pieces for Battleship will be simple 3D models of ships (destroyer, submarine, etc.) or perhaps even flat 2D sprites. The track for Trouble will be a colorful, straight-forward path. There will be no dynamic lighting, no particle effects, and no environmental storytelling. The “world” is the board game board, rendered with all the artistic flair of a PowerPoint diagram. The perspective is top-down, a perfect choice for board game translation but executed with no cinematic flair.

- Sound Design: The soundscape will be equally sparse. It will consist of:

- A few short, repetitive MIDI-style musical loops—likely jaunty and inoffensive for the menu and each game.

- Stock sound effects for placing a ship, moving a peg, fitting a piece, and the digital equivalent of the pop-o-matic clack.

- A repetitive, grating “game over” or “win” jingle.

There will be no voice acting, no dynamic audio that reacts to gameplay tension (the rising tempo in Perfection might be a basic, looped sped-up track), and no ambience. The sound exists only for functional feedback.

These elements contribute to the overall experience by creating an atmosphere of profound cheapness and disconnection. The player is not immersed in a “world” but is instead looking at a functional, digital replica of a physical object. The experience is one of recognition, not absorption—”Oh, that’s the Trouble board,” not “I’m on the Trouble board.”

Reception & Legacy: The Sound of Silence

The critical and commercial reception of the Battleship / Trouble / Perfection Collection is, for all practical purposes, a null set. Metacritic lists a “tbd” Metascore and User Score with zero critic or user reviews. MobyGames shows it is “Collected By” only 2 players (as of the latest data), a staggering statistic for a commercially released Windows game. MyAbandonware and the Internet Archive have preserved it as abandonware, a clear sign of its commercial failure and subsequent obscurity. There are no reviews on IGN, GameSpy, or Kotaku—these sites either never covered it or their content has been lost to time, a fitting metaphor for the game’s own erasure.

Its influence on the industry is nonexistent. It did not pioneer a new monetization model (that honor goes to freemium mobile games), nor did it inspire a wave of high-quality board game adaptations. Instead, it is a culmination of a dying trend: the late-2000s, retail-focused “shovelware” compilation. Its legacy is as a negative space, a example used by critics and historians (this very review) to define the bottom of the barrel. It stands in stark, pitiful contrast to the era’s acclaimed collections (like The Orange Box, Metroid Prime Trilogy), which bundled premium experiences with care and often new features. This collection offered the opposite: the absence of care, the presence of a license.

The related games listed on MobyGames—Perfection. (2013), Puzzle Perfection (2013), etc.—show that the Perfection brand had a longer digital life, often on mobile platforms in more thoughtful, genre-specific iterations. The Battleship / Trouble / Perfection Collection represents a dead-end branch on that evolutionary tree, a clumsy attempt to port a physical social experience onto a PC without understanding its social context.

Conclusion: A Perfectly Imperfect Artifact

The Battleship / Trouble / Perfection Collection is a failure as a video game. It is unengaging, visually barren, and sonically repetitive. It provides no new insight into its source material, offers no compelling reason to play digitally instead of on a physical table, and lacks any feature—online matchmaking, robust AI, customizable rules, presentation flair—that would justify its existence beyond the most basic convenience.

However, as a historical document, it is almost perfect. It captures the terminal phase of an era where video games were still sold in boxes on store shelves, where a publisher could license three beloved family brands, outsource their development for a pittance, and expect to move units based on name recognition alone. It is the digital equivalent of a dollar-store puzzle: assembled from recognizable pieces, but with a frayed box, missing instructions, and a picture on the front that bears little resemblance to the blurry, poorly printed reality inside.

Its place in video game history is not on a pedestal, but in a museum of economic folly and creative bankruptcy. It is the quiet, unassuming ancestor to the modern free-to-play, ad-laden mobile knock-off. It proves that a compilation’s value is not in the sum of its parts, but in the intention behind their assembly. Here, the intention was purely transactional. The result is a collection that, ironically, is perfectly forgettable—a silent, empty chair at the digital board game table, awaiting a player who will never come.

Final Verdict: 1.5/10. A historically significant piece of “shovelware” with zero recreational merit, serving only as a stark lesson in the perils of license-driven, low-effort game development.