- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Beijing Unistar Software Co., Ltd., UserJoy Technology Co., Ltd.

- Developer: UserJoy Technology Co., Ltd.

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Gameplay: characters control, Combination skills, Multiple units, Real-time, Troop management, Wargame

- Setting: Ancient, China, Imperial

Description

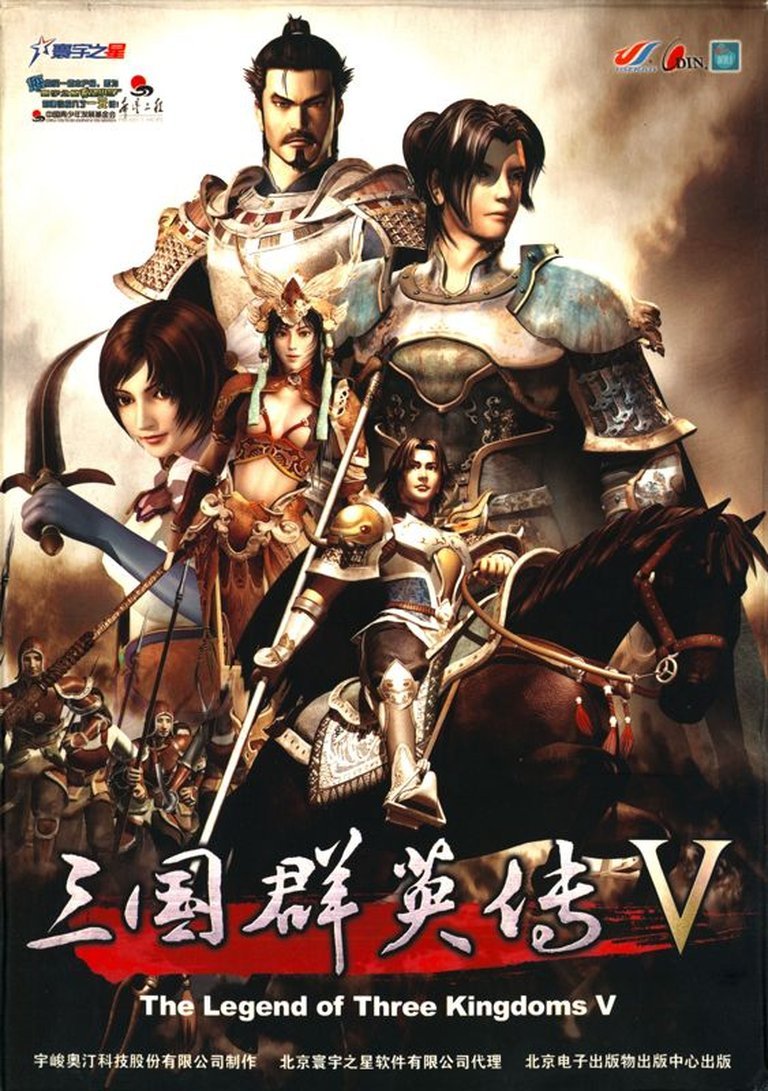

Set in ancient China’s Three Kingdoms era, Heroes of the Three Kingdoms 5 is a real-time strategy wargame where players command large armies with up to 1000 soldiers per side, engaging in tactical warfare featuring unique combination skills cast by multiple officers.

Heroes of the Three Kingdoms 5 Guides & Walkthroughs

Heroes of the Three Kingdoms 5: A Vibrant But Overlooked Bridge in Eastern Strategy Design

Introduction: The Dragon’s Horde Awaits

In the vast pantheon of video games inspired by China’s tumultuous Three Kingdoms period, most Western gamers’ gaze immediately locks onto Koei’s hallowed Romance of the Three Kingdoms grand strategy series or the殿堂级 (diǎntángjí – “hall of fame”) spectacle of the Dynasty Warriors musou action games. Yet, nestled in a rich, homegrown tradition largely invisible to the West until digitally preserved platforms like Steam brought it to light, lies the Heroes of the Three Kingdoms series—or Sanguo Qunying Zhuan—by Taiwanese developer UserJoy Technology. Its fifth installment, released in 2005, arrives not as a mere iteration but as a bold, if flawed, statement: a real-time wargame built on a foundation of colossal, screen-filling battles and a unique “combination skill” system that prioritizes dramatic officer duels and tactical formations over macro-economic management. Heroes of the Three Kingdoms 5 (HotK5) is not the deep, statecraft-focused sim of its Koei rivals. Instead, it is a vibrant, chaotic, and stubbornly idiosyncratic celebration of the era’s legendary warfare, a game where the thunderous charge of a thousand troops under a single heroic banner is the ultimate currency. This review will argue that while HotK5 suffers from a sometimes-archaic interface and a thematic narrowing of the Three Kingdoms’ grandeur into pure combat, its unwavering focus on visceral, large-scale tactical engagement and its innovative officer-centric mechanics secure it a unique and cherished place in the niche canon of Eastern historical wargames.

Development History & Context: From Taiwanese Pixels to Global Steam

The Studio and the Series Vision: UserJoy Technology (later宇峻奥汀, or UserJoy/Aurora, after a merger) emerged in the late 1990s as a specialist in historical strategy titles for the Chinese-speaking market. The Heroes of the Three Kingdoms series debuted in 1998, carving its niche by emphasizing real-time battlefield command and hero officer duel mechanics, a deliberate departure from the turn-based, province-conquering focus of Koei’s dominant series. By the time of HotK5’s release on February 1, 2005, the series was a established franchise in Taiwan, China, and parts of Southeast Asia, with four prior entries steadily iterating on its core real-time wargame formula.

Technological Constraints and Aesthetic Choice: The year 2005 placed HotK5 in a transitional period for PC gaming. While Western strategy titles were increasingly embracing 3D environments (Rome: Total War released in 2004, Company of Heroes in 2006), UserJoy made a conscious, practical decision to double down on a polished 2D sprite-based engine. The source material notes a key upgrade: the “picture clarity has been fully upgraded to 1024*768 resolution,” allowing for more detailed unit and officer sprites. This was not a limitation born solely of budget, but a design choice that served the game’s primary ambition: to render “super-large battles with thousands of people on the same screen.” The 2D, diagonal-down perspective ensured that hundreds of individual soldiers remained visible and readable during chaotic engagements, a feat far more challenging in early 3D engines of the era. The “Visual” descriptor of “2D scrolling” and “Perspective” of “Diagonal-down” are thus fundamental, not incidental, to understanding HotK5’s visual identity and performance goals.

The Gaming Landscape: In 2005, the historical strategy genre was bifurcated. On one side was Koei’s detailed, menu-heavy, and turn-based Romance of the Three Kingdoms series (with RTK IX released in 2003 and X in 2004). On the other was the burgeoning Western real-time strategy scene defined by Blizzard’s Warcraft III (2002) and the resource-gathering, base-building paradigm it popularized. HotK5 existed in a space between, and largely apart from, these giants. It shared the real-time pacing with Blizzard’s titles but rejected base-building and resource gathering for a pure, army-centric command model. It shared the Three Kingdoms setting with Koei but rejected the geopolitical simulation for a more personal, hero-driven conflict. This made it a cult classic within its target demographic but a obscure curio elsewhere, a fate sealed by the lack of an official Western localization until its 2020 re-release on Steam.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The General’s Burden, Not the Emperor’s

The narrative framework of HotK5 is both its greatest strength in immersion and its most significant point of divergence from the broader Three Kingdoms literary and gaming tradition. It is not a story of Liu Bei’s moral righteousness, Cao Cao’s political cunning, or Sun Quan’s defensive tenacity in a grand, dynastic sweep. Instead, the narrative is hyper-localized to the general’s tent and the battlefield’s edge.

Plot and Structure: The game presents a series of historical and semi-historical scenarios set during the late Han dynasty’s collapse and the subsequent tripartite struggle. Players assume the role of a warlord (or “monarch,” as the MobyGames description states), but the campaign is a sequence of discrete battles and city sieges, not a continuous narrative with scripted dialogue trees or character-driven cutscenes. The “plot” is the Three Kingdoms itself—the legendary battles of Red Cliffs, Guandu, and the conquest of Yi Province—recreated as playable campaigns. The focus is relentlessly tactical: capture this city, defeat that enemy general, survive that ambush.

Characters as Game Mechanics: The officers (or “heroes”) are the true protagonists. Drawing from the novel’s vast roster—Cao Cao, Lü Bu, Zhuge Liang, Guan Yu—each is not just a unit but a combat entity with unique stats, personal troops, and, most critically, combination skills. Dialogue is minimal, relegated to pre- and post-battle flavor text and officer introductions. The novel’s rich themes of brotherhood (the Oath of the Peach Garden), betrayal (the assassination of Yuan Shao’s sons), and philosophical debate between Confucian loyalty and Legalist pragmatism are almost entirely absent from the interactive layer. They exist as backdrop, a reason to field these specific figures, but the gameplay asks nothing of the player in terms of moral choice or political maneuvering.

Thematic Core: The Cult of the Warrior-Hero: Where HotK5 shines thematically is in its pure, unadulterated celebration of the zhūjiàng (武将) – the warrior-generals. The game’s heart is the one-on-one duel. When two officers meet in battle, the action can pause or zoom in for a dramatic, animated clash where special “combination skills” can be unleashed. This system elevates individual combat prowess to the supreme factor in victory. The theme becomes clear: in this interpretation of the Three Kingdoms, history is shaped not by grain supplies or popular support, but by the steel of a hero’s blade and the morale of his personal retinue. It’s a thrillingly asymmetric view, where a player’s most valuable asset might be a single, über-powerful officer capable of breaking an entire enemy formation through repeated use of a potent combination skill. This contrasts sharply with Koei’s simulations, where a brilliant strategist like Zhuge Liang might have low combat skill but high political and intelligence stats for governing and plotting. In HotK5, Zhuge Liang is, first and foremost, a battlefield commander who can incinerate troops with fire attacks.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Symphony of the Thousand-Man Battle

HotK5’s gameplay is a purist’s real-time tactics engine, stripped of all pretense of empire management. Understanding its systems requires dissecting its core loop and its most defining innovation.

Core Gameplay Loop: The loop is elegantly, brutally simple:

1. Deployment: At the start of a scenario (either campaign or custom battle), the player allocates a limited number of “officers” to their side. Each officer commands a “troop” of soldiers.

2. Command: The player directly controls one officer at a time (though groups can be selected), issuing move orders, attack commands, and triggering “combination skills.” The other AI-controlled officers follow basic hold/attack/advance orders.

3. Engagement: When officer-controlled troops collide with the enemy, a real-time melee ensues. Soldier sprites clash in a swirling melee, with flurries of sword strikes and arrow volleys rendered in 2D sprite animation.

4. Resolution: Victory is achieved by either annihilating all enemy officers or forcing the enemy commander to retreat (often by reducing their personal “HP” bar to zero in a duel). Morale is a hidden factor; routing troops are visibly depicted as panicked sprites fleeing the field.

The Combination Skill System – Innovation and Flaw: This is HotK5’s signature mechanic and its most analyzed feature. The “combination skills which are casted by multiple officers” (per the MobyGames description) are context-sensitive special attacks. When two or more allied officers are in proximity and their “skill points” have charged (through combat), a player can trigger a cinematic, screen-shaking combo attack. The most basic is a dual-attack between two officers. More advanced skills require three, four, or even all five officers on the field to be positioned correctly for a devastating “Grand Combination.”

* Innovation: This system creates a powerful tactical layer centered around positioning and timing. It rewards players for keeping their officers grouped, turning the army into a synergistic organism rather than a collection of independent units. The visual spectacle of five legendary warriors simultaneously executing a screen-filling finishing move is the game’s ultimate payoff, directly channeling the dramatic, heightened reality of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms novel.

* Flaws: The system can be frustratingly specific in its requirements. Positioning five officers perfectly in the heat of battle is a micro-management nightmare. Furthermore, because these skills are so powerful, they can trivialize challenging battles if used correctly, or make battles feel hopeless if the player’s officers are too separated or their skill gauges are depleted. It creates a “high-risk, high-reward” dynamic that some players find exhilarating and others find game-breakingly inconsistent.

Soldier Management and Scale: The jump to a maximum of 1,000 soldiers per side (5 troops of 200) is a headline feature. This scale is achieved through the 2D sprite engine, allowing for genuinely impressive vistas of clashing armies. However, the tactical control is blunt. Soldiers under an officer’s command fight as a cohesive block with no individual squad micromanagement. There is no “flanking bonus” or complex formation system beyond the officer’s innate “formation” stat (e.g., arrow, square, spear). The scale is therefore largely cosmetic and morale-based; a troop of 200 is simply a larger health pool and damage dealer for its commanding officer. This reinforces the hero-centric design: the soldiers exist to amplify the officer’s power, not to act as an independent force.

User Interface (UI) and Controls: The interface is a telling artifact of its era and regional origin. It is menu-heavy and dense, reliant on numerous hotkeys (the Steam community discussions mention issues with “switching out” of the game causing “花屏” or screen corruption, a common issue with older DirectDraw/Direct3D transition games). Selecting units, issuing advance/attack/hold commands, and activating combination skills require familiarity with a key layout that offers little intuitive guidance. There is no modern right-click-move or streamlined control group system. This creates a significant accessibility barrier for modern players but is part of the authentic, “hardcore” appeal for the dedicated fanbase that persists (as seen in the 84/100 “Very Positive” rating from 242 Steam reviews, with players discussing strategies for specific officers like “五虎将大队” – Five Tiger Generals squads).

Comparison and Positioning: Mechanically, HotK5 has more in common with the arena-battler Heroes of Might and Magic (in its map-screen battles) or a very specific subset of Japanese Touhou Project fan-games (bullet-hell patterns applied to army units) than with StarCraft or even Koei’s RTK. It is a duel-and-skirmish simulator sandboxed within the Three Kingdoms setting. The lack of economy, diplomacy, or even a strategic layer (you don’t move armies on a overworld map between battles in the core mode; you select scenarios) is its defining feature and its greatest point of divergence from nearly every other strategy game in the setting.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The 2D Grandeur of Ancient China

The setting is the Three Kingdoms period as mythologized in Luo Guanzhong’s 14th-century novel. HotK5 does not simulate this world; it illustrates it through its art and scale.

Visual Direction and Atmosphere: The game’s world is the battlefield. There is no overworld map to explore, no cities to view except as static backdrops during siege scenarios. The atmosphere is generated entirely by the diagonal-down, 2D scrolling battlefield. The upgrade to 1024×768 resolution, while rudimentary by today’s standards, was a significant leap for the series, allowing for larger, more detailed officer sprites with distinct animations for different weapon types (spears, swords, halberds). The soldiers are smaller, simplified sprites that mass together to create the illusion of a “thousand-man” battle. The color palette is earthy and muted—browns, greens, and greys—for soldiers, with more vibrant reds, blues, and golds for high-ranking officers to ensure they stand out in the fray. The art style is firmly in the “traditional Chinese illustration” vein, with characters designed to match classical depictions (long beards for Guan Yu, a stern visage for Cao Cao) rather than historical accuracy.

The “world-building” is thus purely aesthetic and contextual. It is built through the juxtaposition of these iconic character sprites against large, simple landscape tiles (plains, hills, rivers) and the dynamic chaos of the sprite-based melee. It captures the “epic” feeling of the era through sheer scale and iconic imagery, not through environmental storytelling or depth.

Sound Design: The source material is completely silent on the game’s sound design and music. This is a critical gap. Based on era-appropriate UserJoy titles and similar East Asian PC games of the period, one can infer a soundtrack likely featuring traditional Chinese instrumentation (gu Zheng, pipa, percussion) attempting to evoke a “warrior’s” or “dynastic” feel, though perhaps synthesized and repetitive. Sound effects would be a mix of standard “sword clash,” “arrow whoosh,” and “cavalry hoof” samples common to the genre. The absence of any mention in reputable sources suggests the audio was functional and unremarkable, not a standout feature. This is a common trait in many mid-budget Asian strategy games of the 2000s, where resources were visibly prioritized for sprite work and battle mechanics over orchestral scores or advanced audio implementation.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Classic Sustained by Emulation and Steam

Critical and Commercial Reception at Launch: HotK5 was never reviewed by major Western outlets at the time of its 2005 release. Its reception was entirely within its native Chinese-language gaming press and retail channels. The Metacritic and MobyGames pages, even today, show a critical vacuum (“Critic reviews are not available for Heroes of the Three Kingdoms 5 PC yet”). The game was a commercial success in its intended market—Taiwan, China, and diaspora communities—as a follow-up to a established series. It was not a breakout hit that crossed cultural barriers but a solid, anticipated entry that satisfied its core fanbase.

Evolution of Reputation: The game’s reputation has undergone a quiet renaissance through digital preservation and backwards compatibility. Its 2020 re-release on Steam, published by UserJoy and Phoenix Game, is the primary reason it is discussed at all in English today. This re-release, priced at a paltry $3.99, introduced it to a new audience of “expatriate gamers,” historians, and enthusiasts of niche strategy games. The Steam community page is active, with discussions in Chinese primarily focused on technical troubleshooting (“游戏中切换出来会花屏怎么解决?” – How to solve the screen corruption when switching out of the game?) and nostalgic strategy sharing (“五虎将大队” – Five Tiger Generals squads). The Steam review score of “Very Positive” (84/100 from ~242 reviews as of early 2026) is the clearest modern reception metric. It indicates a small but fiercely dedicated player base that values its unique combat and is willing to forgive its archaic interface.

Influence and Industry Place: HotK5’s direct influence on the global industry is negligible. It did not spawn clones or inspire Western developers. Its legacy is internal to the Chinese/Taiwanese PC gaming scene. It represents a peak of UserJoy’s specific real-time wargame formula before the series evolved. Heroes of the Three Kingdoms 6 (2006) and 7 (2007) iterated further, with Kingdom Heroes 8 (2021) showing the studio still exploring this vein. More broadly, it stands as a counter-example to Koei’s dominance. It proved there was a market for a Three Kingdoms game that rejected grand strategy for intimate, hero-focused tactical mayhem. Its model of “one officer = one powerful unit with special combos” can be seen as a precursor, in spirit if not in detail, to the officer-centric mechanics in later Japanese musou games and certain MOBA hero designs, though a direct lineage is speculative.

In the vast library of Three Kingdoms games, HotK5’s place is that of the specialist’s tool. It is for the player who wants to reenact the duel between Guan Yu and Huang Zhong, not manage grain taxes in Chengdu. It is a game that understands the power fantasy of the Three Kingdoms is not in ruling an empire, but in being the invincible general at its head.

Conclusion: A Flawed, Vibrant Artifact of a Bygone Design Epoch

Heroes of the Three Kingdoms 5 is not a perfect game, nor is it an essential classic for all strategy fans. Its interface is clunky by modern standards, its strategic depth effectively nonexistent outside of the immediate battle, and its sound design forgettable. Its narrative is a skeletal frame for its mechanics. Yet, to dismiss it on these grounds is to miss its singular achievement: the creation of a real-time tactics engine that makes the mythological, superhuman scale of the Three Kingdoms heroes feel tangibly, viscerally playable.

The thrill of triggering a “100-man Slash” combination skill with five legendary officers, watching their sprites converge in a burst of light and devastating damage across a densely packed enemy army of a thousand sprites, is an experience no grand strategy map or turn-based menu system can provide. It captures a specific, cinematic fantasy of ancient Chinese warfare that is deeply embedded in the popular imagination through novels, operas, and comics.

Its legacy is secure as a cult masterpiece and a vital data point in the study of regional game design. It demonstrates a viable alternative to the Koei model, one that prioritized action and spectacle over simulation. Preserved on Steam for a few dollars, it remains accessible, if niche, for those willing to grapple with its archaic UI. For the historian of strategy games, Heroes of the Three Kingdoms 5 is a fascinating testament to the enduring appeal of its source material and the diverse, often isolated, ecosystems of game development that have interpreted it. Its final verdict is this: a flawed, frustrating, but ultimately brilliant and heartfelt tribute to the age of dragons and heroes, best enjoyed not for its depth, but for its spectacular, fleeting moments of chaotic, thousand-man glory.