- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: 1C Company, Cryo Interactive Entertainment, DreamCatcher Interactive Inc.

- Developer: In Utero

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Action, Adventure, Combat, Puzzle, Transformation

- Setting: 1890s, Belle Époque, City – London

- Average Score: 34/100

Description

Jekyll & Hyde is an action-horror game set in 1890s London, loosely based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic novel. Players control Dr. Jekyll as he transforms into his monstrous alter ego, Mr. Hyde, to rescue his kidnapped daughter Laurie from an insane asylum inmate, overcoming zombies and other monsters while collecting magical artifacts within a single night.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Jekyll & Hyde

PC

Jekyll & Hyde Free Download

Jekyll & Hyde Guides & Walkthroughs

Jekyll & Hyde Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (34/100): It’s among the worst action-adventure games ever released and is so crippled by confusing camera angles and bad control that it seems less like a game and more like a parody of its genre.

neoseeker.com : the graphics in this game are poorly detailed and the character models look bad and weak, mostly because they are disturbingly distorted.

gamesreviews2010.com : Jekyll & Hyde is a timeless adventure game that combines a gripping storyline, challenging puzzles, and thrilling action sequences.

Jekyll & Hyde: A Flawed Masterpiece of Ambition – An Historical Review

Introduction: The Promise of a Dual Legacy

In the annals of licensed video game adaptations, few titles have been as simultaneously ambitious and bedeviled as Jekyll & Hyde (2001). Based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s timeless 1886 novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde—a story that has spawned hundreds of film, theatrical, and literary reinterpretations—the game arrived at a pivotal moment for the adventure genre. The era was defined by the tumultuous shift from 2D point-and-click to 3D real-time exploration, a transition that claimed many victims. Developed by the Parisian studio In Utero and published by Cryo Interactive (in Europe) and DreamCatcher Interactive (in North America), the game promised a mature, horror-tinged take on the classic tale, swapping the subdued psychological horror of the book for a full-throated plunge into Gothic action-adventure. Its legacy is not one of commercial triumph or universal acclaim—with a MobyGames critic score of 53% and notoriously scathing reviews—but of a fascinating, deeply flawed artifact. It stands as a testament to a small studio’s artistic vision battling against technological constraints, rushed schedules, and the unforgiving mechanics of 3D game design. This review will argue that Jekyll & Hyde is a cautionary tale of Renaissance-era ambition in a time of industrial assembly, a game whose sublimely eerie atmosphere and innovative core concept are perpetually at war with its punishingly poor controls and obtuse design.

Development History & Context: The In Utero Ethos and the Cryo Crunch

The story of Jekyll & Hyde cannot be separated from its developer, In Utero, and its publisher, Cryo Interactive. In Utero was a tight-knit Parisian studio of about 20 people during the game’s development, a number Jocelyn Tridemy (Artiste3D/LD on the project) notes was typical for the era, with a culture of cross-disciplinary flexibility. “There was less documentation to do,” he recalled in a detailed preservation interview. “If an idea seemed interesting we would do it.” This fluid, instinct-driven approach was both the studio’s greatest strength and its Achilles’ heel.

In Utero was riding high on the success of their first self-developed title, Evil Twin: Cyprien’s Chronicles (2000), a similarly stylized 3D platformer-adventure. Jekyll & Hyde was conceived as a way to generate revenue while polishing their “baby,” Evil Twin. The development cycle was astonishingly short—about a year—a deadline that would prove catastrophic for polish. The game utilized the same proprietary Phoenix3D engine (and accompanying I.S.A.A.C. toolset) as Evil Twin, meaning the foundational tech was proven but inflexible. This reuse is evident in the similar graphical style and some asset concepts shared between the titles.

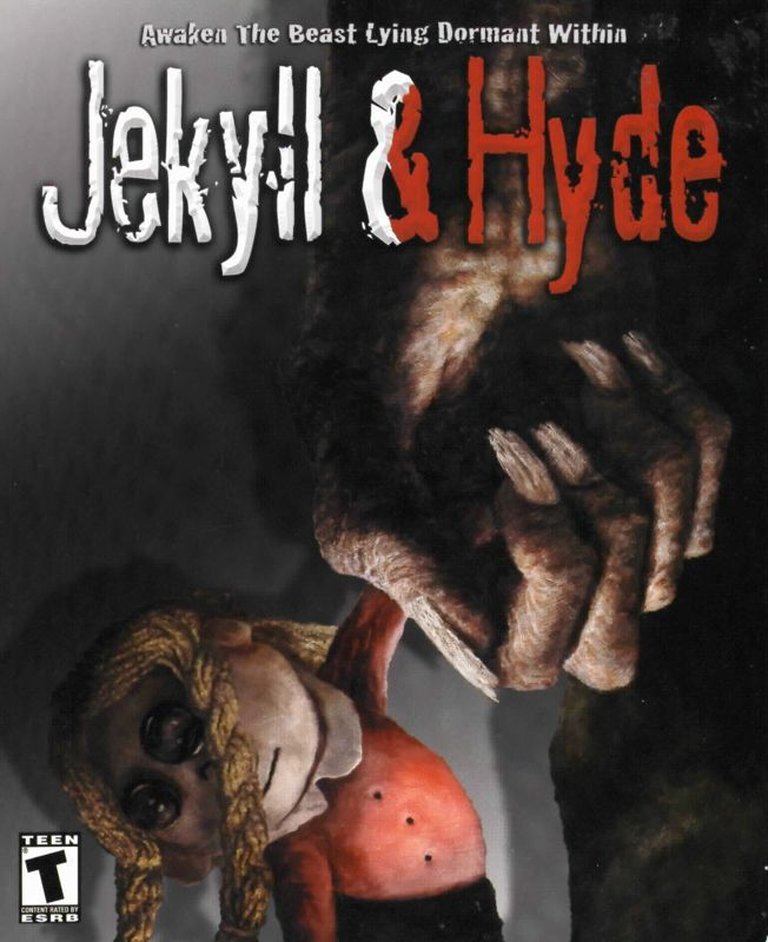

Crucially, the project’s artistic vision was locked to the distinctive, angular, and grotesque illustrations of French comic book artist Stéphane Levallois. Artistic Director Anthony Lejeune was tasked with translating these 2D designs into 3D models, a process fraught with difficulty. “Some sketches had to be adapted because they were either impossible or complicated to reproduce digitally,” the preservation site notes. A cape attached to a character’s arms, for instance, would have required prohibitively complex cloth simulation, forcing a costume redesign. The team used Photoshop filters to create a deliberately “trashy” texture style to match Levallois’s look, resulting in the game’s most celebrated and divisive feature: a visual identity that is simultaneously ugly, expressive, and perfectly attuned to the game’s oppressive atmosphere.

The partnership with Cryo Interactive was a classic publisher-developer dynamic of the time. Cryo, known for narrative-driven adventures like Atlantis: The Lost Tales, gave In Utero smaller projects to “earn money.” Jekyll & Hyde was one such order. As Tridemy put it, “Cryo was a publisher that tried things without knowing if they would succeed.” This risky, sometimes haphazard approach extended to licensing; the article suggests Cryo sometimes began development on licensed games before securing the rights, ready to retheme if necessary. The North American publisher, DreamCatcher Interactive, was a prominent distributor of European titles, often with mixed results.

Technologically, the game was a product of the Windows 95/98/ME era, targeting a Pentium II 300MHz with 64MB RAM. The constraints were severe by modern standards but typical for 2001. The team’s own admission is damning: “The development team couldn’t make the game they wanted to make because of their limited gameplay skills.” They were artists and level designers, not yet masters of the nascent “3Cs” of game design (Camera, Control, Character). “We didn’t know what the 3Cs were,” Tridemy admitted. “We did a lot of things on instinct.” This instinct produced a unique aesthetic but failed in the fundamental mechanics of interaction.

A poignant footnote is the cancelled Dreamcast port. Prototypes from September and December 2000 have since been preserved and released online. They reveal a version in active development with key differences: the ability to switch between Jekyll and Hyde at will (a cut feature from the PC version), different control schemes, and partially implemented levels. The port was underway when In Utero filed for bankruptcy in 2001, sealing the fate of both the Dreamcast version and the studio itself. Many former In Utero staff later joined Ubisoft Paris, carrying their experience forward.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: From Psychological Duality to Vampire Cult MacGuffin

Stevenson’s novella is a masterclass in subtle psychological horror and societal repression. The game, however, retains only the superficial skeleton of the premise, injecting it with pulp adventure and occult conspiracy. The year is 1890 London, a city steeped in the grimy, gaslit reality of Jack the Ripper’s London, as faithfully recreated in the game’s environmental storytelling.

The plot, as detailed in the official descriptions and the NeoSeeker review, is a significant departure. Dr. Henry Jekyll, now the director of an asylum, has vanquished his alter ego, Mr. Hyde, following his wife’s death, dedicating his life to his daughter, Laurie. The inciting incident is a kidnapping by a patient named Burnwell, who leads an uprising and poisons the asylum’s supplies. But this is quickly revealed as a complex ruse. Burnwell is a pawn of a vampiric cult led by a mysterious figure called “The Attorney.” The cult’s goal is to force Jekyll to resurrect Hyde to retrieve the stolen Book of Zohar (a real Kabbalistic text, here reimagined as a powerful occult artifact). Hyde must find three metallic pieces of a medallion, held by a Chinese opium den owner (James Yang), an Indian Maharaja, and a Voodoo witch doctor.

This narrative shift from internal, philosophical duality to external, cosmic horror fundamentally alters the story’s meaning. In the game, Jekyll and Hyde are not two halves of a flawed whole but reluctant allies against a greater evil. Hyde is not a manifestation of unchecked id but a necessary, brute-force tool for a greater good—a classic “Papa Wolf” scenario. The themes become less about repression and more about sacrifice, parental love, and occult conspiracy. The “Book of Zohar” MacGuffin and the secret society trope are pure adventure game contrivances, diluting the original’s potent metaphor.

The storytelling is delivered through pre-rendered cutscenes and, more interestingly, through Jekyll’s personal notebook, which he fills with observations as he progresses—a direct nod to adventure game conventions. The voice acting, widely noted as a relative high point (especially for Jekyll), and the disturbing sound design (screams in the distance, creepy music) successfully build a tense, B-horror movie atmosphere. However, the plot’s execution is relentlessly linear and often illogical, a common critique in reviews. The game’s world-building—the asylum, opium den, brothel, cemetery, and cult stronghold—is vivid and grotesque, perfectly capturing the “squalid grandeur” of fin-de-siècle horror, even if the narrative connecting them is thin.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The 3Cs Collapse

Here lies the game’s fatal flaw. The core loop is a third-person action-adventure with a brilliant central conceit: two playable characters with distinct abilities that must be swapped to solve environmental puzzles and combat scenarios.

- Dr. Jekyll is weak, can only jump short distances, and fights with a walking stick (Cane Fu). His strength is puzzle-solving: he can interact with complex mechanisms, pull levers, turn valves, and (critically) use items from his inventory.

- Mr. Hyde is a hulking brute. He jumps farther, deals more melee damage with his claws, and is more resilient. He is utterly incapable of solving most puzzles that require fine motor skill or item use. His transformation is limited, requiring a potion (found in levels) and a container of “pure water” to activate.

This duality is conceptually superb. It forces the player to think about pathway clearing (Hyde breaks barriers, Jekyll operates switches) and creates natural tension: when to transform? How long can Hyde’s potion last? The potential for intricate, character-specific puzzles is enormous.

In practice, the system is undermined by catastrophic technical execution.

-

Camera & Control (The 3C Catastrophe): This is the game’s most universally panned aspect. The camera is described as “temperamental,” “wandering,” and “blocked by walls at critical moments.” The control scheme is often compared to “tank controls” (like early Resident Evil), but worse. Turning is too fast for precise platforming on narrow beams. There is no strafing or backwards walking. The review consensus is brutal: GameSpot called it a “parody of the action-adventure genre,” PC Action said it turns the game into a “nervous, fragmented” experience, and Just Adventure noted the “stink of tediousness.” The Dreamcast prototype’s different button layouts hint at the developers’ own struggle to find a solution.

-

Puzzle Design & Progression: Puzzles range from simple (find key, pull lever) to infamously obtuse and pixel-hunty. The final level is singled out as a “Guide Dang It!” maze where you must break three pillars in different rooms before accessing the final boss—a nonsensical sequence. The TV Tropes page notes an “Easy Level Trick” for the final boss (leave and re-enter the room to reset him), highlighting broken design. Inventory management is clunky; picking up an item requires explicitly placing it in your jacket inventory or it vanishes on level transition (a noted bug in modern abandonware comments).

-

Combat: Universally derided as “lackluster,” “simplistic,” and “awkward.” Enemies (zombies, lunatics, automatons, cultists) are defeated by repetitive “run up and hit” tactics. Robot enemies cannot be killed, only stunned temporarily. There is no dodge or block. The AI is “laughable.” Combat exists as a tedious chore between the real game: traversal and puzzles.

-

Saving & Difficulty: The save system is archaic and punishing. You can only save at designated checkpoints (signified by a fleeting pocket watch icon). Death sends you back to the start of the entire level, forcing you to replay cutscenes and sequences. This, combined with the controls, creates a perfect storm of frustration. GameZone’s complaint that saving options “seem like they have consolitis” points to a poorly considered port-like design.

-

The Lost Dreamcast Feature: The most tantalizing “what if” is the free-form transformation seen in the early Dreamcast builds. Players could switch between Jekyll and Hyde at will, anywhere. This would have revolutionized the puzzle design, allowing for dynamic problem-solving. Its removal for the final PC version—likely due to balancing issues or scripted event constraints—is arguably the single greatest squandered opportunity. It speaks to the project’s instability and the conflict between artistic vision and production reality.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Gothic Masterpiece Trapped in a Broken Engine

If the gameplay is a failure, the atmosphere is a resounding, haunting success. This is Jekyll & Hyde’s redeeming grace and its primary claim to historical interest.

-

Visual Direction & Art Style: The translation of Stéphane Levallois’s illustrations into 3D is the game’s defining characteristic. The world is constructed from bizarre, sharp angles, exaggerated proportions, and deliberately “unclean” textures. Characters are disturbingly elongated or distorted. Environments like the insane asylum, the opium den, the vampire cult’s “Womb Level” (a fleshy, blood-slicked catacomb), and the Toppled Chapel are soaked in a grimy, surreal aesthetic that perfectly captures a David Lynch-meets-German Expressionism nightmare. The NeoSeeker review called it a “bad parody of a David Lynch production” that is “weird, all right, but not exactly engaging”—a fair assessment. It’s sometimes ugly in an artistic way, other times just ugly. The color palette is murky browns, deep reds, and sickly greens. The lighting is dramatic and oppressive. This is not a generic “dark fantasy” world; it is a uniquely French comic-book-gone-horror vision, utterly distinct from the more polished Gothic of Castlevania or the Victorian sterility of The Order: 1886.

-

Sound Design & Music: Universally praised. The sound effects are a key part of the horror: distant screams, clanking chains, squeaking doors, and the unsettling gurgles of Hyde. The voice acting, while not award-winning, is committed and atmospheric, with Hyde’s guttural grunts and Tarzan-like speech providing unintended camp. The score by Bertrand Eluerd (who also worked on Evil Twin) is magnificent—a brooding, melancholic, and often terrifying orchestral/synth hybrid that elevates every moment. Its loss (Eluerd died in 2005) is a minor tragedy for game music historians.

-

Setting & Atmosphere: The game’s 1890 London is less a historical recreation and more a psychological projection of Jekyll’s guilt and Hyde’s savagery. The locations—the asylum, a brothel, a chaotic cemetery, a train, a ship, a cult temple—are less coherent geography and more thematic set-pieces. The level design is often non-Euclidean and confusing, but this sometimes works in its favor, enhancing the dreamlike, disorienting horror. The world feels lived-in, decayed, and actively hostile, which is a triumph of environmental storytelling despite the navigational headaches.

Reception & Legacy: The Critics Were Right (Mostly)

Jekyll & Hyde landed with a thud in 2001. Its Metacritic/aggregate score sits around 34-53% (depending on source), with a brutal distribution: few mixed reviews, mostly negative. The extreme ends are telling: PC Gamer Brasil (89%) praised the visuals and gameplay—likely a regional anomaly or different review standards—while Computer Gaming World (20%) called it a “mockery of good reading material.” The consensus is perfectly captured in the GameSpot (30%) and IGN (27%) headlines: a game crippled by controls and camera, whose few redeeming features (atmosphere, story premise) are drowned in frustration.

The player reception on MobyGames is a low 2.1/5, but the modern user comments on sites like MyAbandonware reveal a cult, masochistic appreciation. Players like “RandalMcdaniels” have undertaken the grim task of mastering its Byzantine inputs, discovering workarounds, and even appreciating its “badsterpiece” quality. This suggests a game that, against all odds, has cultivated a niche appreciation for its sheer commitment to its weird vision, much like the cult following of Deadly Premonition.

Its commercial performance is unclear but implied. It was not a breakout hit. It sold “well despite mediocre reviews,” according to the preservation article, but likely only as a budget title from DreamCatcher’s value line. No sequel was planned. The cancelled PS2 port mentioned in Wikipedia vanished with In Utero’s collapse.

Its influence is negligible to nonexistent on the mainstream industry. It did not spawn imitators. Its ideas—dual-character puzzle-platforming—were executed better elsewhere (e.g., The Lost Vikings, Trine). However, its historical significance is twofold:

- As a culmination of the Cryo/In Utero style: It represents the peak (and endpoint) of a particular strand of mid-2000s European adventure game: heavily narrative, artistically bold, mechanically rigid.

- As a case study in 3D transition failure: It is a textbook example of talented artists and designers failing to grasp the essential “feel” of 3D character control—a lesson that studios like Ubisoft (where many ex-In Utero staff landed) would learn and master in the subsequent decade.

- As a preserved artifact of lost potential: The Dreamcast prototypes are a time capsule, showing a version with a fundamentally more interesting gameplay hook (free switching). It fuels “what could have been” speculation and is a primary source for historians studying the era’s development pipelines and pitfalls.

Conclusion: A Fascinating Ruin

Jekyll & Hyde (2001) is not a good game by any conventional metric. Its controls are agonizing, its camera an active enemy, its combat shallow, and its puzzles often illogical. To play it today is to engage in a sustained exercise in frustration, a constant battle against the interface. The critics of 2001 were, in their harshness, essentially correct.

And yet, to dismiss it entirely is to ignore a crucial piece of gaming’s mosaic. It is a flawed masterpiece of ambition. It is the game where a small, passionate team of French artists, given a tight deadline and a limiting engine, poured every ounce of their creative energy into crafting an atmosphere of profound, unsettling dread. The world they built is unforgettable—a grotesque, beautiful, terrifying caricature of Gothic London that feels more like a waking nightmare than any other game adaptation of Stevenson’s work. Its central duality mechanic, while broken in execution, points toward a more sophisticated kind of adventure gameplay.

Its place in history is secure as a monument to misaligned priorities. It proves that a brilliant artistic vision, without a mastery of fundamental interaction design, cannot succeed. It is the anti-Soul Reaver: where Crystal Dynamics understood that a gothic hero needed weighty, responsive controls to feel powerful, In Utero crafted a hero who feels perpetually clumsy and ill-suited to his world. It is a “noble failure”—a game that aimed for the artistic heights of a Silent Hill or a Myst but stumbled into the abyss of poor 3D implementation. For scholars of game design, it is an essential case study. For the masochistic historian or the curious connoisseur of game weirdness, it is a bizarre, rewarding, and ultimately tragic journey into a mind (and a studio) that dreamt in chiaroscuro but moved in mud. Its ultimate verdict is not “play this game,” but “study this game, learn from its failures, and remember its chilling, beautiful ruins.”