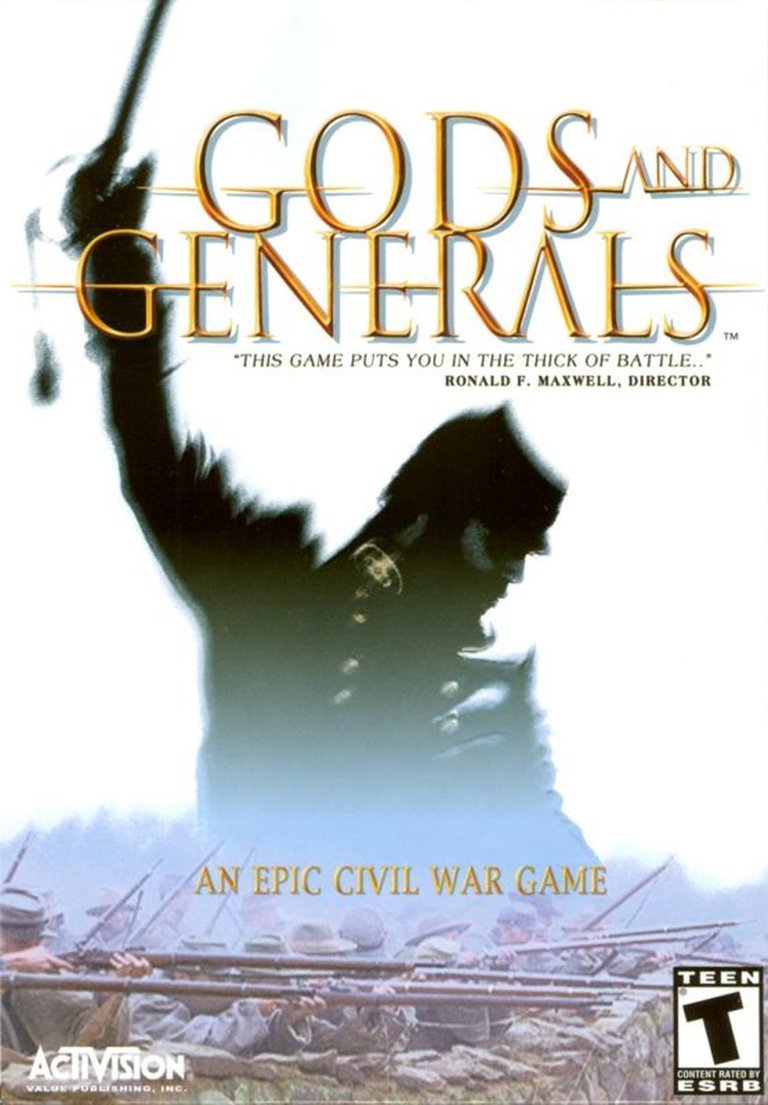

- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Activision Value Publishing, Inc.

- Developer: AniVision

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Historical combat, Mission-based, Shooter

- Setting: American Civil War

- Average Score: 19/100

Description

Gods and Generals is a first-person shooter video game based on the historical film of the same name. Set during the American Civil War, players can choose to fight as either Union or Confederate soldiers in iconic battles such as Chancellorsville, Fredericksburg, and the Second Battle of Bull Run. The game features authentic period weapons like muskets, sabers, and revolvers, and offers diverse missions including reconnaissance, raids, and company commands, with integrated scenes from the movie to enhance the historical experience.

Gameplay Videos

Gods and Generals Free Download

Gods and Generals Cracks & Fixes

Gods and Generals Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (19/100): Outdated graphics, bad sound, lousy control, horrible technical performance, nonfunctional computer AI, terrible weapons–the game has about every problem you could possibly think of.

Gods and Generals: A Historical Shooter’s Descent into Infamy

Introduction: The Charge That Faltered

In the annals of video game history, few titles stand as a more potent symbol of rushed development, misunderstood ambition, and the perils of the movie tie-in than Gods and Generals. Released to coincide with Ronald F. Maxwell’s epic Civil War film in March 2003, this first-person shooter from the obscure Alabama-based studio AniVision promised an immersive, ground-level view of America’s bloodiest conflict. Instead, it delivered a masterclass in failure, earning some of the most scathing reviews in the industry’s history. Yet, to dismiss it solely as a “bad game” is to overlook a fascinating, if tragic, case study. This review will argue that Gods and Generals is a critical artifact of its time—a product of technological constraint, corporate cynicism, and a niche historical passion that, against all odds, carved out a strange, enduring legacy among a tiny subset of players. It represents the bitter end of an era for low-budget licensed games and a stark warning about the gulf between thematic aspiration and mechanical execution.

Development History & Context: A Budget Charge into a Cannonade

The Studio and the Vision: AniVision, led by CEO Robert Wells and President/Game Designer Brian Mitchell, was a small, independent studio with a credited team of 65 people, many of whom also worked on hunting titles like Cabela’s Big Game Hunter. Their vision, as inferred from the source material, was to translate the scale and solemnity of Civil War combat into an interactive FPS format, a stark contrast to the grand strategy of titles like Sid Meier’s Gettysburg!. The goal was authenticity: slow-firing muskets, scarce ammunition, and a focus on individual soldier experience within large battles.

The Tyranny of the Tie-In: The development timeline was dictated not by creative polish but by the film’s release schedule. With the movie premiering on February 21, 2003, the game shipped on March 1. This compressed schedule—likely under a year of active development—is the foundational sin of Gods and Generals. As multiple sources note, this “haste contributed to pervasive technical issues, including poor AI functionality, control problems, and subpar performance.” The game was a promotional tool first and a playable experience a distant second.

Technology and Constraints: The game was built on the LithTech Jupiter engine, a technology from Monolith Productions that had powered the superior No One Lives Forever 2 (2002). Here lies a core irony: the engine was already showing its age by 2003, and its implementation here was notoriously poor. Minimum specs (Pentium III 800 MHz, 128MB RAM, 32MB VRAM) target mid-range early-2000s PCs. However, “unoptimized rendering causing stuttering and crashes on period-appropriate hardware” was a common complaint. The engine struggled mightily with the large-scale battles the game aspired to, leading to severe performance issues and a lack of scalability. Rather than leveraging the engine’s strengths (which included a degree of environmental interaction seen in NOLF 2), AniVision produced a visually dated, technically unstable product.

The Gaming Landscape of 2003: This was the era of Call of Duty (released later in 2003), Medal of Honor: Allied Assault, and Return to Castle Wolfenstein. These were sleek, refined, AAA shooters emphasizing cinematic action and tight controls. Gods and Generals, in contrast, felt like a relic from 1998. Its positioning as a budget title under the Activision Value imprint signaled its lowly status—a cheap cash-grab aimed at Civil War enthusiasts and movie fans, not core gamers.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Ghost of Stonewall Jackson

Plot and Structure: The campaign is a nine-mission linear narrative entirely from the Confederate perspective, mirroring the film’s focus on Generals Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson and Robert E. Lee. It chronologically covers 1861-1863: First Bull Run (three missions), Fredericksburg (one extended mission), and Chancellorsville (five missions). The player is an anonymous company commander (private/sergeant), fulfilling objectives like reconnaissance, raids, sabotage, and holding defensive lines. The narrative is delivered through text briefings and, crucially, integrated video scenes from the film itself, a clear attempt to blur the line between interactive and passive media.

Characters and Dialogue: The player character is a cipher, a vessel for the player. Historical figures like Jackson appear as mission-givers or context, but there is no character arc or personal story. Dialogue is sparse and functional, mostly limited to barked orders from superiors or the occasional movie clip. The thematic weight rests entirely on the player’s perception of the setting and the film’s framing, not on in-game storytelling.

Underlying Themes and The “Lost Cause” Shadow: This is the most fraught aspect of the title. The game, like the film, operates within a specific historiographical tradition. By focusing on Confederate bravery, tactical brilliance (e.g., Jackson’s flanking maneuver at Chancellorsville), and the “gentlemanly” nature of the conflict, it implicitly aligns with aspects of the “Lost Cause” narrative. Critics and modern historians argue this perspective sanitizes the foundational cause of the war—the preservation of slavery—by emphasizing states’ rights, homeland defense, and martial virtue. The game’s language (“Gods and Generals,” the noble tragedy of the South) and its exclusive early-war Confederate viewpoint contribute to this. It presents a warfare simulation that, in its aesthetic and mission framing, can feel like a reenactment of a specific, contested memory of the conflict, prioritizing tactical verisimilitude over moral reckoning. This is not a game about slavery or its abolition; it is a game about the combat techniques and battlefield experiences of soldiers fighting for the Confederacy, a choice that carries significant ideological weight.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The BrokenMusket

Core Loop and Combat: The intended core loop was: traverse linear battlefield -> engage in slow, deliberate musketry or melee -> scavenge ammo from corpses -> complete scripted objective -> repeat. The musket reload was the centerpiece mechanic, designed to emulate the 20-30 second process of loading a black powder weapon. However, its implementation was disastrous. The animation was long, the player was completely vulnerable and immobile, and it often encouraged a cheesy “switch weapon to cancel reload” exploit, utterly breaking the intended tension.

Weapon Arsenal: Period-accurate arms are present: smoothbore/rifled muskets (single-shot), the 1851 Colt Navy revolver (six-shot, equally slow reload), Bowie knives, infantry sabers, and Ketchum hand grenades. The scarcity of ammunition, forcing constant looting from fallen enemies, was a genuine attempt at historical simulation but became a frustrating chore due to poor enemy drop rates and AI.

AI and Enemy Behavior: This is where the game collapses entirely. Critics universally condemned the “nonfunctional” AI. Enemies display no tactical awareness: they fire randomly, ignore cover, clip through terrain, and perpetually respawn in scripted waves. Officer units “do the hokey-pokey,” waving swords without purpose. This destroys any pretense of a meaningful combat simulation, turning engagements into chaotic, unpredictable, and deeply unsatisfying affairs.

Progression and Systems: Missions award experience points for completing objectives, which can be spent on skill improvements (e.g., faster reload, better accuracy). This light RPG element, borrowed from No One Lives Forever 2, is one of the few functional systems. There is a rudimentary squad command mechanic in some missions, but it is clunky and largely irrelevant given the brain-dead AI of your own squadmates.

UI and Controls: The interface is basic but functional on paper. In practice, “unresponsive controls” and “input lag” were major issues. The game’s physics and collision detection are infamous; players regularly get stuck on 2D tree limbs or geometry, a testament to the engine’s poor optimization and level design.

The Specter of Missing Multiplayer: A glaring omission was promised multiplayer support. Reviews noted its absence at launch, with Activision threatening a free add-on that never materialized. This was a critical blow, as linear FPS campaigns of this length (~13 hours) needed a multiplayer component for longevity.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Flickering, Muffled Memory

Visuals and Atmosphere: Powered by LithTech Jupiter, the game’s graphics were “outdated even by early 2000s standards.” Textures are low-resolution, models are simplistic, and environments are barren and repetitive—generic fields, sparse woods, and simple town structures. There is little dynamic lighting or atmospheric effects to convey the smoke and terror of a Civil War battlefield. The visual presentation fails utterly to create immersion, instead highlighting the budget constraints. The inclusion of film clips is arguably the game’s most polished visual asset, creating a jarring contrast between the grainy, cinematic movie scenes and the blocky, soulless in-game engine.

Sound Design and Music: The soundscape is another failure. “Muffled audio effects” and a “lack of spatial immersion” make gunfire indistinguishable from other noises. The soundtrack, drawing on period-appropriate music like “Dixie” and “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” is hampered by “repetitive loops and occasional glitches where effects would cut out entirely.” The potential for a rousing, immersive audio experience is completely squandered.

Historical Authenticity vs. Presentation: There is a clear attempt at period detail in the weapons, uniforms (gray Confederate wool, kepi caps), and battlefields (Marye’s Heights, the Wilderness). However, the poor graphical and audio fidelity strips these elements of any visceral impact. The authenticity exists only in a theoretical, descriptive sense—in the manual and mission briefings—not in the sensory experience of playing.

Reception & Legacy: The Worst of the Worst

Critical Panning: The reception was catastrophic, cementing the game’s infamy.

* Metacritic: 19/100 (“Overwhelming Dislike”).

* GameSpot: 1.2/10, naming it the worst game of 2003. Their review savaged it: “shamelessly steals from… No One Lives Forever 2,” “abysmal,” “a shoddy afterthought of an unrelated marketing campaign.”

* PC Gamer: 20/100, citing “imbecilic AI,” “laughable weapons-modelling,” and “nine sleep-inducing missions.”

* Absolute Games (AG.ru): 5/100, with hyperbolic, vitriolic condemnation recommending the developers be sent to “reed plantations.”

* Only GameZone (60%) offered a nuanced, if still flawed, take, appreciating its “steep learning curve” and “professional feel” for historical buffs, while警告 that it would bore anyone expecting “laser blasts and aliens.”

Player Reception – A Stark Divide: Player scores on Metacritic tell a different story, averaging 7.4/10 based on 64 ratings at the time. This massive gulf (19 vs. 74) is the game’s most intriguing aspect. A small, dedicated group of players valued its Confederate perspective and attempt at historical simulation. For them, the “true to life”experience of slow, tense combat and the rarity of playing as a Confederate infantryman in key battles outweighed the technical filth. These were often history enthusiasts who saw it as a flawed but genuine reenactment tool, a “good learning resource” as one source notes. The critical consensus saw a broken FPS; this niche saw a flawed historical simulator.

Commercial Performance and Disappearance: As a budget Activision Value title, commercial figures weren’t tracked prominently, but the complete lack of sequels, expansions, or patches speaks to its failure. It was effectively abandoned, entering abandonware status. Physical copies are now collector’s items on eBay ($10-$50), sought by the curious or completists.

Legacy in the Industry:

1. The Cautionary Tale: Gods and Generals became the textbook example of how not to make a licensed game. It prioritizes marketing synergy (film clips) over gameplay, rushes development to a fixed date, and uses an ill-suited engine with incompetent implementation.

2. A Historical Gaming Dead End: Its failure arguably stifled serious, non-strategy attempts at Civil War simulation in the FPS genre for years. The bar for historical authenticity in shooters was set so low here that publishers likely feared the niche.

3. Cult of the “So-Bad-It’s-Good”: In the YouTube era (videos from 2020 onward, “Bad Game Hall of Fame”), it has found a second life as a curiosity. Its broken AI, hilarious glitches, and bizarre design choices make it a subject of mockumentary-style playthroughs. It is remembered not for what it intended, but for how spectacularly it failed.

4. A Mirror for Historical Debate: The game exists at the intersection of Civil War memory and interactive media. Its unexamined adoption of the film’s “Lost Cause”-leaning perspective highlights how games can perpetuate historical narratives simply through mechanics and framing, even when their technical quality is negligible.

Conclusion: A Bug-ridden Battlefield in the Memory of Gaming

Gods and Generals is not merely a bad game; it is a catastrophic failure on nearly every measurable level—technical, design, artistic, and commercial. Its animations are laughable, its AI is non-functional, its sound is broken, and its core mechanic (the musket reload) is undermined by its own bugs. GameSpot’s assessment that it is “difficult to imagine… much worse” holds weight.

Yet, its historical significance lies in this very failure. It is the ultimate example of the cynical, deadline-driven movie tie-in. It stands as a monument to the idea that a compelling historical theme and authentic weapons list are worthless without a functional game underneath. Its bizarre afterlife, where a tiny community of historical buffs tries to see past the glitches while the wider world laughs at its incompetence, speaks to the strange, fragmented nature of gaming appreciation.

In the grand strategy of gaming history, Gods and Generals is a minor, forgotten skirmish. But as a case study in failed adaptation, rushed development, and the perils of niche ambition, it is a battle worth studying—if only to understand how not to charge into the marketplace. Its final, brutal verdict is that it is remembered not for the experience of playing it, but for the experience of reading about how terrible it is. It is, in the end, a game remembered only by its reviews, a ghost on the hard drives of those who sought a Civil War simulation and found a bug-ridden, dispiriting march through a broken, half-formed battlefield.