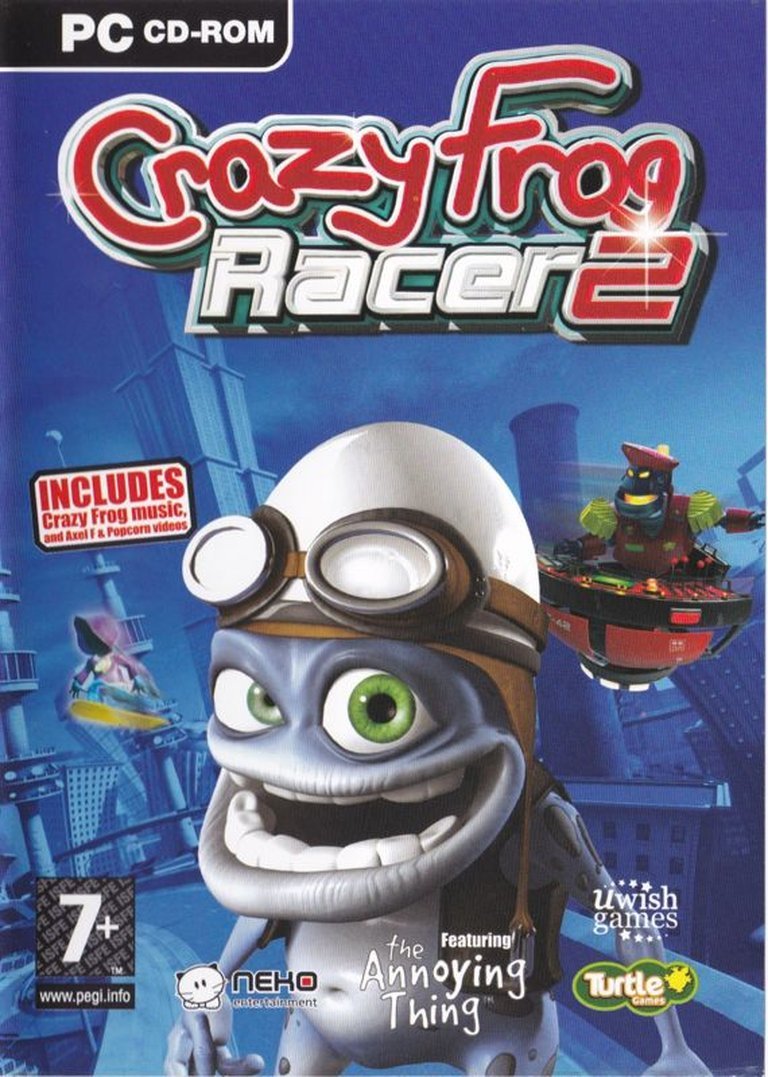

- Release Year: 2007

- Platforms: PlayStation 2, Windows

- Publisher: Turtle Games, Valcon Games LLC

- Developer: Neko Entertainment SARL

- Genre: Driving, Racing

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Combat, Mini-games, Racing

- Setting: Beach, City, Football, Ice

- Average Score: 29/100

Description

Crazy Frog Arcade Racer (also known as Crazy Frog Racer 2) is a 2007 racing game where players compete as the Crazy Frog and friends in various modes, including championships across themed cups like Football, Ice, City, and Beach, single races, chase races, time trials, and mini-games such as Crazy Frog Pinball and Crazy Dance, all featuring music tracks from the Crazy Frog series like ‘Axel F’ and ‘Popcorn’.

Gameplay Videos

Crazy Frog Arcade Racer Reviews & Reception

maxutmost.com : By the Gods of Kusoge, what have I done?

metacritic.com (29/100): This is every bit as stinking as you would expect.

ign.com : Moments ago, I broke through the haze of what most would call ‘reality’ or ‘sanity.’

Crazy Frog Arcade Racer: Review

Introduction: The Annoying Thing Comes to Console

To understand Crazy Frog Arcade Racer (known as Crazy Frog Racer 2 in Europe) is to understand a specific, brutal moment in mid-2000s pop culture: the relentless, inescapable commodification of the “Crazy Frog” phenomenon. Emerging from a Swedish sound effect, morphing into a viral animation of a nude anthropomorphic frog on an invisible moped, and exploding into a global ringtone and music chart juggernaut, the “Annoying Thing” (as it is often called) was less a character and more a sonic and visual irritant, a piece of cultural detritus that somehow commanded billions. Crazy Frog Arcade Racer, developed by France’s Neko Entertainment and released in late 2006/early 2007 for the PlayStation 2 and Windows, is the inevitable, perhaps terminal, video game manifestation of that cash cow. It is not merely a bad game; it is a profound and eloquent artifact of cynical, license-driven development, a title so bereft of artistic intent or mechanical integrity that it achieves a sort of anti-art status. This review will dissect the game not just as a failed racing title, but as a historical document—a meticulously constructed void in interactive entertainment that perfectly mirrors the lowest common denominator impulses of its source material and its era. Its thesis is simple: Crazy Frog Arcade Racer is less a game and more a legal obligation given polygonal form, a product whose every design decision stems from a place of utter contempt for the medium and its audience.

Development History & Context: From Viral Flash to Shovelware

The development of Crazy Frog Arcade Racer 2 is a story of corporate maneuvering and diminishing returns. The original Crazy Frog Racer (2005) was published by Digital Jesters, a company that, per the Crazy Frog Wiki, “went out of business following an investigation.” This chaotic backdrop set the tone. The license for the frog—held by the Wallaroo Licensing Company representing creator Erik Wernquist—was a hot potato of pure commercial IP, passed from dtp Entertainment (GBA) to Digital Jesters (console/PC) and, after their collapse, to Mercury Games. Crazy Frog Arcade Racer was published under Mercury’s subsidiary, Turtle Games, in Europe and Valcon Games in the US.

The developer, Neko Entertainment, was a prolific French studio known for budget-friendly and licensed titles, including the first Crazy Frog Racer, Legend of the Dragon, and the Cocoto series. Notably, the Crazy Frog Wiki and MobyGames credits reveal they reused the exact engine, file systems, and core gameplay code from Crazy Frog Racer 1 & 2 for Cocoto Kart Racer, a clear indicator of the “build once, skin twice” mentality. This was not a bespoke creation but a template with a new (and legally mandated) skin slapped on. The technological context was the tail end of the PS2’s lifecycle, where a flood of cheap, easy-to-produce licensed titles targeted at the casual and children’s market saturated bargain bins. Crazy Frog Arcade Racer landed right as the fad was dying (the last major album was in 2006), making it a belated, desperate cash-grab. The “vision,” such as it existed, was to translate the music video chase sequences and ringtone ubiquity into a playable product with zero regard for gameplay depth or longevity, resulting in a title that feels both instantly dated and mechanically inert.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Plot in Name Only

There is no narrative to speak of. The game’s “story” is presented in the GOG.com dreamlist description: “After winning the cup and escaping the Drone, the Crazy Frog is now ready to shift into the next gear for the craziest race ever!” This is pure after-the-fact justification, a meaningless string of verbs that suggests a sequel without any actual plot. The “Championship” mode’s progression through the Football Cup, Ice Cup, City Cup, and Beach Cup offers no cutscenes, no dialogue, no conflict. You simply race to win trophies.

The thematic content, therefore, must be excavated from the game’s very existence and its DNA. First, it embodies the commodification of absurdity. The Crazy Frog was not a character with lore but a sound and a silhouette. The game attempts to build a world—with a cast of original, “canon foreigner” characters like Bobo, Ellie, Grim, and Jack (per TV Tropes)—around this hollow core. These characters, designed by Digital Jesters, have no narrative purpose; they exist solely to populate a roster, each with stat variations (Fragile Speedster, Mighty Glacier, etc.) that are functionally irrelevant in a game with such poor track design and physics. The “Annoying Drone,” introduced in this sequel, is a literal evil knockoff, a thematic echo of the frog itself being a knockoff of a moped sound.

Second, the game is a study in adaptational modesty and sanitization. The source material featured a frog with a visible penis. The game, rated PEGI 7, removes this entirely, presenting a family-friendly, neutered abomination. The contrast between the transgressive, internet-bred origins and the sterile, legally-safe product is jarring. It speaks to the soul-crushing process of mainstreaming viral culture: strip away anything actually interesting or provocative, leave only the brand recognition and the sonic hooks.

Finally, the game’s structure reinforces a theme of pointless repetition. The core modes (Championship, Single Race, Chase Race, Time Trials) are endless variations on the same hollow loop. The Chase Race—where you simply drive to avoid drones—is described by IGN as “something that you start up and give to a three year old to keep them happy for a few minutes.” This is the thematic core: the game is a digital pacifier, designed not for engagement but for quieting, a interactive equivalent of blaring “Axel F” to drown out a child’s complaints. It’s interactive babysitting, a theme perfectly aligned with its low-effort, low-reward design.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Sanding Off of Friction

At its mechanical heart, Crazy Frog Arcade Racer is a kart racer clone following the Mario Kart template but missing every single element that makes that formula work. The core racing is defined by a catastrophic lack of friction—both literal and metaphorical.

Core Racing Loop: Players select a character (each with four stat categories: speed, acceleration, road-holding, weight on a 1-6 scale, though IGN notes none visually exceed 2) and race across 12 tracks (unlocked via cups). Coins are collected on-track, which are then used to “buy” power-ups from a selection menu while driving, a unique twist from the usual random box pickup, as documented on the Crazy Frog Wiki. The power-ups are standard fare: dumbfire missiles, poison clouds, and two types of shields (one defensive, one offensive/tackle). There are also repair items (nuts and bolts) for the “vehicle condition” gauge, which depletes when hit and causes a wipeout at zero.

The Frictionless Abyss: The most damning design choice is the track architecture. As the Maximum Utmost review masterfully articulates, “you don’t lose very much speed when you rub up against a wall.” This removes the core tension of kart racers: the risk-reward of cutting corners versus hitting walls. Combined with wildly twisting, undulating tracks full of sudden drops and jumps (described as “a rejected WipEout course”), the result is a game where skill feels impossible. The narrow paths and aggressive elevation changes mean failure is often not from poor driving but from the game’s own geometry. You cannot learn tracks through muscle memory because the physics are so floaty and the consequence of falling off is inconsistently telegraphed. It’s a racing game that actively discourages precision.

Chase Mode & Mini-Games: The other modes are equally hollow. Chase Race is a treadmill of despair. You drive endlessly around a track while slowly being whittled down by nearly ineffective drones. As Maximum Utmost notes, the enemies are “so ineffective” that the mode becomes a test of patience, not skill. The two mini-games are Crazy Dance (a Bemani-style button-tapper on the numeric keypad) and Crazy Frog Pinball (a bizarre, paddle-less pinball where you aim the frog’s launch direction). Both are simple, pointless distractions that exist solely to pad the feature list and, critically, to force the player to listen to the music—the game’s true, punitive core.

Multiplayer & Battle Mode: Two-player modes include Championship, Single Race, and a unique Battle Mode where players fight in arenas with three lives. This is the closest the game comes to mindless fun, but it inherits all the core combat’s limp weapons and poor hit detection.

In summary, the gameplay is a cascade of failures: no sense of speed, bad vehicle handling (per AceGamez), lame power-ups, and a total lack of meaningful progression (no unlockable parts, only characters and cups). The unique coin-based system is a curiosity but is neutered by the tracks’ design and the items’ mediocrity.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Aesthetically Bankrupt, Auditory Assault

Visuals & World-Building: Against all odds, the game is technically competent in its art assets. IGN remarks, “visually, the game is pretty damn impressive… the models themselves are really rather detailed.” The tracks, themed around the Crazy Frog music videos, include a Skyscraper City (from “Axel F”), Palmtree Panic Beach (from “Popcorn”), a Slippy-Slidey Ice World, and a Space Zone. They are colorful, with a “pop” reminiscent of early 3D Sonic titles. However, this competence makes the failure worse. The world-building is profoundly generic. These are not cohesive worlds but pastel-hued pastiches with zero unique geometry or memorable set-pieces. As Maximum Utmost laments, “I would not be able to point out a memorable track gimmick in any of them.” They are interchangeable, empty shells. The character designs, while distinct (Ellie the fairy, Michel the evil chef), are ripped from a generic kart racer template and have zero connection to the source material’s aesthetic. The “Adaptational Modesty” is complete: the Annoying Thing is now a clothed (or at least not explicitly nude) racer, stripped of all transgressive identity.

Sound Design: The Torture Engine: This is the game’s defining, monstrous feature. The soundtrack consists of Eurobeat remixes of pop songs: “Hey Baby,” “I’m Too Sexy,” “Final Countdown,” “Axel F,” and “Popcorn.” The Crazy Frog’s vocal interjections (“ding-ding-ding,” “ba-ding!”) are layered over these tracks. The result is not music but an auditory weapon. As Maximum Utmost writes, “These songs are some of the worst of it. Easy, repetitive hooks that worm their way into your brain and refuse to leave.” IGN calls it a replacement for waterboarding. Because the gameplay is so frictionless and undemanding, there is no mental engagement to distract from the soundtrack. You are a captive audience to this sonic assault. The sound effects are generic library fare, but they are irrelevant—the music is the point. It is the game’s primary, brutalist mechanic: to punish the player’s ears as a precondition for playing. The inclusion of the actual music videos (“Axel F” and “Popcorn”) as unlockable content completes the circle of abuse, offering no escape from the Frog’s domain.

Reception & Legacy: A Critical Knights Templar of Shovelware

Critical Reception: The game was universally panned. MobyGames aggregates critic scores to a brutal 23% (8 reviews), with Metacritic’s PS2 metascore at 29. Reviews used a lexicon of pure contempt:

* DarkZero: “every bit the lazy cash-in… broken in the most important places and just plain dull or irritating in the rest.”

* AceGamez: “less-than-mediocre gameplay, no sense of speed, bad vehicle handling, lame power-ups… no reason for this piece of tat to exist.”

* Jeuxvideo.fr (0%): “Moche, pas maniable, capable de faire regretter à Dieu d’avoir fourni des oreilles aux hommes” (Ugly, unplayable, capable of making God regret giving men ears).

* Play.tm: “an astoundingly poor title that represents all that is putrid and rotten about the tsunami of franchise/licensed/tie-in dross.”

* IGN: “probably dangerous enough to be classified as a controlled substance.”

The consistent themes were: lazy asset reuse (recycled track layouts from the first game, as noted on TV Tropes), abysmal music, pointless modes, and a profound sense of wasted time. The sole, faint praise consistently went to the visuals—a backhanded compliment that highlighted the disconnect between technical polish and design bankruptcy.

Commercial & Cultural Legacy: Despite critical evisceration, it likely sold adequately on the back of the Crazy Frog brand, especially in Europe. Its legacy is threefold:

1. The Apotheosis of the Shovelware License: It stands as a textbook example of the mid-2000s “license-treadmill” model. A fading fad, a cheap development studio with an existing engine, a publisher desperate for a quick return. It represents the nadir of cynical product placement in games.

2. A Curio of Nostalgic Recidivism: User reviews, particularly on Metacritic and Backloggd, reveal a fascinating schism. While critic scores are abysmal, user scores are mixed (6.3 on Metacritic), with a surprising number of 10/10 reviews. Comments like “The best game ever! GTA: San Andreas can’t surpass this game!” (ironic or sincere?) and more poignant, “The game of my childhood!… I shed a tear. It was my favorite game” (Backloggd) point to a nostalgia filter. For a generation of very young children in 2006-07, this was one of their first gaming experiences. Its sheer simplicity and recognizable IP created a fondness that utterly blindsides critical analysis. It is, for some, a kusoge (awful game) cherished for its awfulness.

3. An Engine’s afterlife: The most tangible legacy is technical: its engine directly birthed Cocoto Kart Racer (2007). The DNA of Crazy Frog Arcade Racer—its handling, its track construction, its menu systems—lives on in another obscure kart racer. It is a ghost in the machine of gaming’s bargain bin.

Conclusion: A Vacancy with a Soundtrack

Crazy Frog Arcade Racer is not the worst game ever made. That title belongs to games that are broken, unplayable, or actively malicious. This game is something more insidious: it is competently empty. It functions. It has menus. It lets you race a frog that sounds like a dial-up modem around a pastel track while “The Final Countdown” plays. But it offers nothing. No challenge, no joy, no artistry, no satirical edge, no tactile feedback, no memorable moment. It is a perfect vacuum.

Its place in video game history is not as a classic, but as a cautionary epitaph. It is the final, gurgling note of an era where viral fads were mined for games with the same rapaciousness as they were mined for ringtones. It demonstrates that a game can have flawless technical execution (the models are detailed, the frame rate stable) and be utterly failed at the experiential level. It proved that you could have a license, a development studio, a publisher, and distribution channels and still create a product with the interactive depth of a looping GIF.

For the historian, it is a vital data point: the moment the industry’s addiction to cheap licensed goods fully revealed its aesthetic bankruptcy. For the player, it is a curious artifact of childhood for some, and for others, a two-hour ordeal that, as IGN said, will leave you “trying to iron French toast ‘just to get the wrinkles out.'” It is the sound of a franchise not just dying, but being ground into dust and sold back to you as a game. The final verdict is not a score, but a diagnosis: Crazy Frog Arcade Racer is a symptom of a disease that still plagues the industry—the belief that a brand name is a substitute for a game. It failed, completely, but its failure is so pure, so concentrated, that it glows with a strange, educational light. Study it to understand what happens when every single creative decision is dictated by legal contracts and spreadsheet projections, leaving only the hollow shell of play.