- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: JVC Digital Arts Studio, Inc.

- Developer: JVC Digital Arts Studio, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Dodging, Shooter

- Setting: 1940s

Description

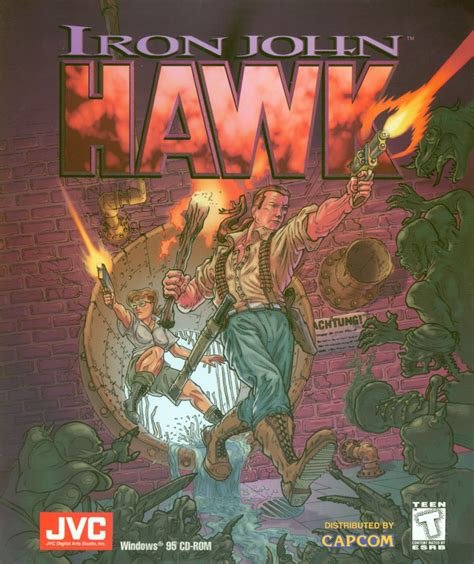

Iron John Hawk: The Shards of Power is an action-adventure game set in 1944, following treasure hunter Iron John Hawk as he crash-lands on the Pacific island of Diablo after a mission gone awry. His quest to find his missing father and the mystical Lemurian Shard of Power leads him into conflict with Nazi Wehrmacht forces, deadly wildlife, pirates, and skeleton warriors, all presented through isometric shooter gameplay with pre-rendered 3D art and dodging mechanics.

Gameplay Videos

Iron John Hawk: The Shards of Power Free Download

Iron John Hawk: The Shards of Power: A Forgotten Artifact of Late-’90s Ambition

Introduction: The Ghost in the Machine of Gaming History

In the vast, crowded archives of PC gaming history, certain titles reside in a peculiar limbo—not celebrated as classics, nor infamous as infamous disasters, but existing as spectral footnotes, almost entirely erased from collective memory. Iron John Hawk: The Shards of Power (1998) is one such ghost. Conceived in the shadow of Indiana Jones and the ascendant isometric action-RPG paradigm set by Diablo, it represents a fascinating, if deeply flawed, collision of pulp adventure, World War II intrigue, and early 3D experimentation. This review seeks to exhume this obscure title from the digital grave, not to champion it as a lost masterpiece, but to analyze it as a compelling case study of ambition hamstrung by technological constraints, narrative incoherence, and the sheer brutal competition of the late 1990s software market. Its legacy is not one of influence, but of caution—a reminder that a compelling logline and competent art assets are not sufficient to overcome fundamental design missteps.

Development History & Context: JVC’s Brief, Baffling Foray

The game was developed and published by JVC Digital Arts Studio, Inc., a name that primarily evokes high-end consumer electronics (VHS, camcorders) rather than game development. This is not a studio with a storied lineage like Blizzard or Capcom; it was a peripheral venture by a hardware giant attempting to dip a toe into the.content creation waters. The collaboration with Capcom, listed on some databases, is intriguing but poorly defined—likely a publishing or distribution partnership for certain regions, rather than a co-development effort, given Capcom’s own强劲 slate of games in 1998 (Resident Evil 2, Mega Man Legends).

The team, led by Lead Programmer Wade Brainerd and Art Director Glenn Price, was a 48-person ensemble. Their credits reveal a mix of experienced programmers (Brainerd, Olson, Richey) and a large, dedicated art team handling pre-rendered 3D and 2D assets. This points to a project where the visual scope—the promise of lush, isometric 3D environments—was prioritized, perhaps at the expense of iterative gameplay design. The era’s technological constraint was the pre-rendered 3D isometric perspective. This technique, used brilliantly by Blizzard North in Diablo and Diablo II, involved creating 3D models and lighting scenes in a 3D application, then rendering fixed-angle sprites. It offered gorgeous, detailed art with minimal in-game GPU demand, but it came with severe limitations: fixed camera angles, environments that couldn’t be dynamically altered, and character animation that was often stiff and limited to predefined cycles.

Iron John Hawk was released into a hyper-competitive market. 1998 was a peak year for PC gaming: Half-Life, StarCraft, Grim Fandango, Thief: The Dark Project, and Fallout 2 all launched. Against such titans, a generic-looking action-adventure from an unknown studio with no recognizable franchise IP was virtually invisible. Its release on Windows 95 and distribution via CD-ROM was standard, but it lacked any digital distribution footprint or modern re-release, cementing its obscurity.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Pulp Clichés in a WWII Maze

The plot, as gleaned from MobyGames and TV Tropes, is a pastiche of well-worn adventure tropes. Set in 1944, it stars “Iron John” Hawk, a treasure hunter in the vein of Indiana Jones, whose father has gone missing. This disappearance is mysteriously linked to the “Lemurian Shard of Power,” a mystical artifact (Lemuria being a fictional sunken continent from esoteric mythology). Hawk’s journey to uncover the truth culminates in a plane crash on Diablo Island, a fictional Pacific locale.

What follows is a laundry list of genre antagonists:

* The Wehrmacht: Nazis are present in force, establishing a base on the island. TV Tropes notes they have created a bestiary of scientific experiments, documented in an “All There in the Manual” in-game document that explains the island’s monstrous wildlife.

* Pirates: A timeless addition for any island-based adventure.

* Skeleton Warriors: The obligatory undead menace.

* Giant Crabs & Scorpions: The “Giant Enemy Crab” and “Scary Scorpions” TV Tropes entries highlight the creature-feature aspect.

The narrative’s driving question—”What happened to Hawk’s father?”—is never meaningfully explored in the available materials. There is zero indication of sophisticated dialogue, character development, or thematic depth. The story is a simple MacGuffin chase. The Lemurian Shard is Applied Phlebotinum; it exists to motivate the hero and justify the fantastical elements on a historically-grounded ( WWII ) island. The fusion of historical WWII with pulp fantasy (zombies, giant monsters, lost artifacts) is conceptually fun but, as the game’s reception suggests, poorly executed. The setting promises The Rock or Castle in the Sky but delivers something more akin to a disjointed monster movie where the Nazis are just another wave of cannon fodder.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Isometric Impasse

Gameplay is described as an isometric perspective action game with shooter mechanics. The core loop is likely: explore static, pre-rendered environments, shoot enemies with found guns, and dodge around scenery. This “dodge” mechanic is a key, if poorly documented, feature—suggesting an attempt at tactical positioning in a fixed-camera view, which is a notoriously difficult design challenge.

Deconstructing the Systems:

1. Perspective & Movement: The fixed isometric camera creates inherent problems. Enemies can emerge from off-screen, leading to unfair ambushes. “Hallway Fight” tropes indicate cramped interiors where maneuvering is impossible, turning combat into a shooting gallery. The ability to “dodge around scenery” implies cover mechanics, but in a static perspective, identifying usable cover and judging line-of-sight is fraught with frustration.

2. Combat & Progression: Players “pick up guns,” suggesting an inventory or weapon-swapping system. There is no mention of RPG elements (stats, skill trees), positioning it firmly as an action game rather than an action-RPG. Progression is likely linear or based on key collection to access new areas, a common trope for the era but one that can lead to backtracking bloat.

3. UI & Flaws: The “Exploding Barrels” trope—”hard to see and tell which one’s an exploding barrel”—is a devastating critique. It points to poor visual signaling, a critical failure in an action game where environmental interaction is key. If players cannot distinguish hazard from décor, the environment becomes a minefield of frustration rather than a tactical tool.

4. Innovation? There is no indication of meaningful innovation. The game seems to be a synthesis of Diablo‘s presentation and Duke Nukem/X-COM‘s top-down shooting, but without the former’s addictive loot loops or the latter’s tactical depth. The “dodge” mechanic, if well-implemented, could have been a differentiator, but the barrel issue suggests it was not.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Pre-Rendered Facade

The game’s visual identity is its pre-rendered 3D isometric art. The team of 3D and 2D artists, led by Kouros Moghaddam and Dana Williams, would have built detailed 3D models of environments, characters, and enemies in software like 3D Studio Max or LightWave 3D, then rendered them from a fixed angle with pre-calculated lighting. This technique could produce stunningly atmospheric and detailed stills. One can imagine the potential: a misty jungle beach with a giant scuttling crab, the stark concrete of a Nazi bunker illuminated by flickering fluorescents, a crumbling ancient temple overgrown with vegetation.

However, this technique also immobilizes the world. Animations are limited to sprite cycles. Water doesn’t flow, flags don’t whip, and lighting is static. The atmosphere must be entirely conveyed through these frozen moments. The description of “giant crabs” and “skeleton warriors” suggests a desire for spectacle, but the technological pipeline would struggle to animate such creatures convincingly in real-time. The “JVC 1701-D” logo joke on the crashed plane’s tail is a cute, self-referential easter egg, but it also subtly underscores the game’s identity as a branded product first and a cohesive world second.

Sound Design is completely unmentioned in the sources. This is telling. For a game relying heavily on atmosphere—jungle sounds, ocean waves, Nazi base clatter, monster roars—the absence of any noted credit or mention in reviews suggests it was either generic, forgettable, or technically deficient. In an era where System Shock 2 and Thief were using sound as a primary gameplay and horror element, Iron John Hawk’s silence on this front is a significant omission.

Reception & Legacy: The 20% Benchmark

The reception is tragically simple: one critic reviewed it. Computer Gaming World (CGW), the venerable magazine, awarded it 20% (1 out of 5 stars), with the scathing verdict: “Unless you’re trapped in an airport with just your PC and a copy of IRON JOHN, you’ll want to avoid this turkey.” This is a death sentence in the pre-internet, magazine-driven review ecosystem. A single, catastrophic review could sink a game’s retail prospects entirely. There is no record of user reviews on MobyGames, and its collection by only 2 players (as of the last update) on that database confirms its utter obscurity.

Its commercial performance was undoubtedly disastrous. It vanished from shelves nearly instantly, leaving no imprint on sales charts or cultural conversation. Its legacy is one of erasure. It has no spiritual successors, no remasters, no cult following. The “Shards of Power” naming ironically links it, via search algorithms, to a whole family of unrelated modern indie games (e.g., Shards of Infinity, Shards of Magic), further burying it in digital noise.

However, a faint, ironic legacy exists in the career trajectories of its developers. As the MobyGames “Collaborations” data shows, key personnel like Wade Brainerd (50+ other games), Tim Tran (88 other games), and Kirby Miller (41 other games) went on to lengthy careers in the industry. Brainerd, in particular, would later work on major titles like the Spider-Man games mentioned. Iron John Hawk thus becomes a professional stepping stone—a project that, for better or worse, provided experience on a shipped title during a formative period for 3D game art and programming.

Conclusion: verdict on a Vanished Relic

Iron John Hawk: The Shards of Power is not a “bad game” in the entertaining, so-bad-it’s-good sense. It is a profoundly mediocre and meaningless artifact. It fails to achieve the camp charm of a Night in the Woods or the broken ambition of a Big Rigs. Its sin is one of utter anonymity. It demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of what made its contemporary hits successful: Diablo’s compulsive loot loop, Half-Life’s seamless narrative integration, Grand Theft Auto’s emergent sandbox. It offers a static world with unclear objectives, frustrating combat, and a narrative that is generic even by pulp standards.

Its place in video game history is as a negative artifact. It is a lesson in the perils of chasing visual trends (pre-rendered 3D) without a strong gameplay core, of lacking a unique selling proposition in a saturated market, and of the catastrophic impact of a single devastating review in a pre-review-aggregator era. It is the professional equivalent of a student film with a competent crew but no script—all surface, no substance. We preserve and study it not for what it is, but for what it represents: the countless, quiet failures that pave the road for the few, brilliant successes. It is a shard of power that shattered on impact, leaving no trace but a faint, unhealed divot in the landscape of 1998.

Final Verdict: 20% is generous. A forgotten, functionally obsolete relic of a bygone publishing era, of interest only to institutional historians and perhaps a handful of developers tracing their career lineages. Avoid at all costs, unless your specific research niche is “obscure isometric action games of the Diablo clone era.”