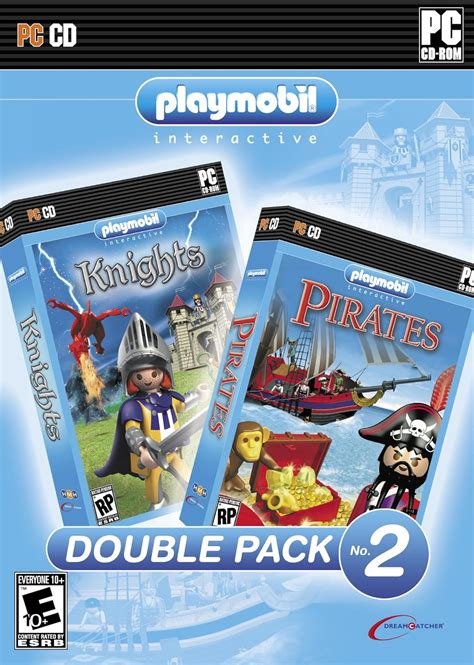

- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: DreamCatcher Interactive Inc.

- Genre: Compilation

Description

Playmobil Double Pack No. 2 is a Windows compilation released in 2010 by DreamCatcher Interactive that bundles two distinct Playmobil-themed games: Playmobil Knights, which immerses players in medieval adventures with knights, castles, and quests, and Playmobil Pirates, which sets sail on high-seas escapades featuring pirate crews, ships, and treasure hunts. Aimed at family-friendly entertainment with an ESRB rating of Everyone 10+, this collection offers accessible gameplay inspired by the iconic Playmobil toys, providing varied settings from castle fortresses to ocean voyages.

Playmobil Double Pack No. 2: A Historical Artifact of Licensed Children’s Software

Introduction: Presinting a Plastic Legacy in Pixels

In the vast and often-overlooked archives of licensed children’s software from the late 2000s, few compilations represent a more specific intersection of toy culture, European game development, and North American publishing than Playmobil Double Pack No. 2. Released for Windows in early 2010 by DreamCatcher Interactive, this bundle—containing Playmobil Knights and Playmobil Pirates—is not merely a product but a document. It captures the twilight phase of the “Playmobil Interactive” brand, a licensing experiment that began with Ubisoft’s ambitions in the late 1990s and was, by this point, being shepherded to retail by the German studio HMH interactive for a global audience. This review argues that the game’s historical and cultural significance far outweighs its immediate play value. As a meticulously preserved time capsule, Double Pack No. 2 exemplifies the “play pattern adaptation” model of children’s game development—where direct, literal translation of physical toy play into digital mechanics was prioritized over innovative gameplay—and serves as a quiet endpoint to a particular era of budget-friendly, faith-based digital adaptations for iconic European toy lines.

Development History & Context: The Final Gasp of an Interactive Brand

To understand Playmobil Double Pack No. 2, one must trace the winding path of the “Playmobil Interactive” label. The initiative was born from a 1998 meeting between Ubisoft executive Alain Tascan and Playmobil owner Hans Brandstätter at the Nuremberg Toy Fair, a legendary venue where toy and licensing futures were forged. Ubisoft’s vision in the late ’90s produced higher-budget 3D adventures like Laura’s Happy Adventures and Hype: The Time Quest, which aimed for a more immersive experience.

However, the licensing stewardship shifted. By the mid-2000s, development duties had largely transferred to the German studio HMH interactive (sometimes listed as Morgen Studios in other contexts for related titles), with publishing handled by entities like Global Software Publishing and later DreamCatcher Interactive. The games in Double Pack No. 2—Knights (2010 DS, but PC version contemporaneous) and Pirates (2008 DS, repackaged)—are quintessential products of this HMH era. They represent a deliberate pivot from Ubisoft’s 3D adventures to a formula built on mini-game collections and simple mission structures, likely driven by tighter budgets and a focus on direct replicability of the Playmobil play experience.

The technological context is the late-stage Windows XP/Vista era, a time when budget PC titles for children still thrived in retail bins alongside office software. The “Double Pack” concept itself was a common marketing tactic (see The Sims 2 Double Deluxe, Castlevania Double Pack), offering perceived value by bundling two standalone products. For DreamCatcher, a publisher known for localization and budget titles, this was a low-risk, high-distribution strategy for a trusted brand. The “Everyone 10+” ESRB rating, with its descriptors of “Comic Mischief, Mild Cartoon Violence, Mild Language,” perfectly encapsulates the sanitized, adventure-book tone these games aimed for.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Archetypal Plots in Plastic

The narratives within Double Pack No. 2 are not complex tapestries but direct reflections of their respective Playmobil playset themes, executed with the simplicity of a children’s picture book.

In Playmobil Knights, the protagonist is not a pre-established figure but “a radish farmer with dreams of being a hero”—a deliberately Everyman origin. The plot is a classic fantasy quest: the kingdom is pillaged by the evil magician FlimFlam and his dark knights, who have captured the King’s knights. The hero’s journey is framed around a single, legendary objective: stealing the Magical Sword from FlimFlam. The narrative acts as a thin veneer for a progression system where helping townspeople earns the right to compete in the King’s tournament, ultimately leading to the rescue of Princess Laura from Dragon Stronghold. The themes are pure chivalric archetype: proving one’s worth through deeds, the triumph of good over stereotypical “dark” magic, and the rescue of the damsel. The use of a “radish farmer” as the hero is a charmingly mundane touch, directly echoing the child’s ability to imagine any Playmobil figure in any role.

In Playmobil Pirates, the setup is equally archetypal but swapped for the high-seas. Players join “One-Eye” (a clear nod to pirate tropes) on a “thrilling trip up and down the Caribbean.” The core objective is a “big treasure hunt” that involves discovering countless islands. The eBay product description provides a clearer, if slightly different, narrative strand: protagonists Laura and Alex must “take over Capt’n Blackbeard’s ship to escape from the island they’re stranded on” before discovering the treasure. This introduces a slight conflict with the GameSpy description’s focus on One-Eye, suggesting the game may blend narrative voices or that Laura/Alex are the player avatars within One-Eye’s story. The primary antagonist is the iconic pirate Blackbeard. Themes here are of exploration, freedom, and adventure against a established (if softened) historical villain. The “kidnapped mermaid” mentioned in the “Everything Explained” source for the DS version does not appear in the Double Pack’s listed description for the PC compilation, indicating potential narrative streamlining or difference between platforms.

The combined package’s narrative thesis is clear: active participation in cherished Playmobil fantasy scenarios. There is no overarching “Double Pack” story; the two games are isolated thematic experiences—medieval knighthood and Caribbean piracy—allowing a child to choose their preferred plastic fantasy.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Mini-Games as Play Pattern Translation

The gameplay philosophy is explicitly stated in the promotional features. For Knights: “Play through 11 different mini games all linked by fast paced action.” For Pirates: “12 Separate missions to complete” with “4 Levels of difficulty offers hours of fun.” This is the core design: a hub world (the kingdom or the Caribbean) from which the player accesses discrete, self-contained challenges.

Deconstructing Playmobil Knights: The game is a mini-game compilation wrapped in a light adventure shell. The “linked by fast paced action” suggests a simple overworld where walking to a location triggers a mini-game. These 11 mini-games are designed to “promote eye and hand coordination, concentration and observation,” revealing its edutainment underpinnings. One can infer a suite of familiar casual activities: memory matching (finding items), simple action sequences (jousting?), puzzle-solving (helping a townsfolk), and perhaps collection tasks. The progression is tied to the tournament structure—winning mini-games builds reputation to face FlimFlam. The “beautiful 3D” recreation of the Playmobil universe is a key selling point, aiming for a direct visual translation of the toys’ charming, scaled-down realism.

Deconstructing Playmobil Pirates: This title leans into a mission-based structure within an “Extensive 3D gaming world.” The 12 missions are likely more involved than simple mini-games, possibly involving sailing between islands (a navigation mechanic), on-foot exploration, and interactions with NPCs. The 4 levels of difficulty are a significant design choice, acknowledging a wider age range within the “10+” bracket and allowing the game to grow with the child. The core loop is probably: receive mission (e.g., “Find the key on Skull Island”), traverse a 3D environment, complete a task (which may itself be a mini-game or a simple fetch/action quest), return for reward, and unlock the next mission. The confrontation with Blackbeard is likely the culmination of these missions.

Comparative Analysis: Knights feels more like a mini-game olympics with a fantasy skin, while Pirates feels more like a simple adventure game with discrete objectives. Neither features sophisticated RPG mechanics, complex combat, or deep narrative choices. Their innovation lies not in revolutionary systems but in their faithful, accessible adaptation of the open-ended “jobs” and “adventures” children create with physical Playmobil figures. The difficulty levels in Pirates are the most notable systemic feature, providing a scalability rare in such straightforward children’s software.

Flaws are inherent to the model: The games are almost certainly repetitive, with thin gameplay loops. There is no character progression beyond unlocking the next mission or mini-game. The UI is designed for absolute simplicity, with large icons and minimal text. They are, by design, not games for enthusiasts but for children, and their systems reflect that priorities: clarity, repetition, and direct correlation to the toy’s imaginative play over any pretense of deep interactivity.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Visual Fidelity of Plastic

The battle for these games was always going to be won or lost on authenticity. The source material repeatedly emphasizes the “charming Playmobil Universe, all recreated in beautiful 3D.” This was the mandate from the licensor, geobra Brandstätter: “the shape and color of each individual digital Playmobil element had to be approved.”

The art direction, therefore, is not an interpretation but a digital scan of an aesthetic. The world is composed of the soft, rounded geometry, primary color palette, and slight stylization of the mid-2000s Playmobil sets—think the detailed but not overly realistic textures of the Pirates ships or the Knights castle. The 3D engine, likely a simple, proprietary one from HMH, would have focused on clear, bright visuals with minimal lighting effects, ensuring a child could easily parse the environment. The goal was immediate recognition: a child seeing the digital knight’s helmet should instantly know it matches the one in their toy box.

Sound design follows suit. The music is likely cheerful, melodic, and non-intrusive, with simple melodies that evoke adventure (trumpet fanfares for Knights, shanty-like tunes for Pirates). Sound effects are iconic and plastic: the clack of a mini-game success, the splash of water, the creak of a ship’s wheel, the neigh of a horse—all reminiscent of the sounds a child might make while playing physically. Voice acting, if present at all, would be sparse, clear, and warmly narrated, avoiding complex dialogue to maintain accessibility for a global, young audience.

The atmosphere is one of sterile, safe adventure. There is no threat, only playful challenge. The “mild cartoon violence” is limited to jousting or perhaps a playful cannonball, always consequence-free. The world is permanently sunny, the seas calm, the castles majestic but welcoming. It is a digital diorama, perfect for its purpose.

Reception & Legacy: A Quiet Commercial footnote and a Brand’s Sunset

Critical Reception: There is a profound absence of contemporary critical discourse. On MobyGames, the title has a “n/a” Moby Score and is “Collected By 1 players.” The “Reviews” page for both the main entry and the specific title on MobyGames is empty, stating “Be the first to add a critic review.” GameSpy and IGN pages from the era contain only the boilerplate publisher descriptions, not reviews. This is not an oversight; it is a reflection of reality. Playmobil Double Pack No. 2 existed in the “bargain bin” sector of gaming journalism—titles that received minimal, if any, coverage from mainstream outlets. It was a product for parents and grandparents buying for young children at mall software kiosks or big-box stores, not for gamers reading previews.

Commercial Reception: While hard sales figures are unavailable, its presence on multiple retail listings (eBay, as seen, with numerous sealed copies still available) and its bundling strategy suggest it met a modest, expected commercial need. It was a stock item for the “kids’ PC games” shelf. Its bundling of two completed titles (Knights and Pirates) was a value proposition that moved units in a crowded marketplace of casual and educational software.

Legacy and Industry Influence: The legacy of Playmobil Double Pack No. 2 is symbolic, not mechanical.

- The End of an Era: As detailed in the “Everything Explained” source, the Playmobil Interactive label was “largely abandoned” after 2012’s Playmobil Pirates (a Gameloft mobile title). The subsequent games either were simple advergames or removed the “Interactive” branding entirely. Double Pack No. 2, released in 2010/2011, sits near the end of this specific branding and development approach. It represents the last concerted effort to release a PC-focused, multi-title compilation of the classic HMH-style Playmobil games in the West.

- A Model of Faithful Adaptation: Its development philosophy—strict visual adherence, direct play-pattern translation—would eventually be supplanted. As mobile gaming exploded, the approach shifted to simpler, more mechanism-driven games (Piraten on iOS/Android was a “construction and management simulation”) or augmented reality gimmicks (Kaboom!). The packaged PC game with hub worlds and mini-games became obsolete.

- Archival Significance: Today, its primary value is as digital preservation. The Internet Archive link, containing the actual ISO images, is crucial. It preserves not just the games, but the specific HMH interactive implementation of the Playmobil aesthetic and gameplay for that era. For historians studying licensed software, toy-to-game adaptations, or early 2000s children’s software pipelines, this compilation is a primary source.

- No Direct Influence: It did not spawn clones, inspire major developers, or innovate in gameplay. Its influence is in demonstrating a sustainable, if low-profile, business model for toy licenses for over a decade—from Ubisoft’s early attempts to HMH’s output—before market forces (rise of mobile, changing toy interests) rendered it unviable.

Conclusion: A Verdict for the Archive, Not the Playroom

Playmobil Double Pack No. 2 cannot be judged by the metrics of gaming excellence. It has no intricate storytelling, no balanced combat, no emergent gameplay. To evaluate it as a “game” in the traditional sense is to misunderstand its fundamental purpose. It is a digital extension of a toy line, a transactional product designed to extend the Playmobil play experience onto the family computer with 100% brand fidelity.

As a piece of software, it is almost certainly adequate: serviceable 3D, clear objectives, sufficient content for its target age group, and a respectable value proposition at retail. Its four difficulty levels in Pirates show a commendable awareness of varying skill levels. But it is profoundly average.

As a historical artifact, it is exceptionally valuable. It marks the commercial culmination of a specific licensing relationship and development methodology. It is the last clear echo of the Ubisoft-era ambitions filtered through the cost-effective, compliance-focused HMH model. Its existence, preservation, and the complete lack of contemporary discussion around it are its legacy. It represents the quiet, unassuming endpoint of a 12-year experiment in bringing the precise magic of plastic Playmobil figures directly to the screen—an experiment that would ultimately be abandoned not because it failed, but because the world of play moved on to touchscreens and different forms of interaction.

Therefore, the final verdict must be bifurcated:

* For the Child of 2010: A perfectly functional, visually faithful, and engaging-enough set of adventures based on beloved toys. A successful product.

* For the Game Historian: An essential, datable specimen. A 1.2GB time capsule of a licensing philosophy, a development studio’s output, and a retail strategy that has since vanished. Its significance is not in what it does, but in what it represents: the final packaged breath of “Playmobil Interactive.” It earns its place not on a shelf of great games, but in the indexed archives of gaming’s collateral history.