- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: ValuSoft, Inc.

- Genre: Compilation

- Setting: Hunting, Outdoors

Description

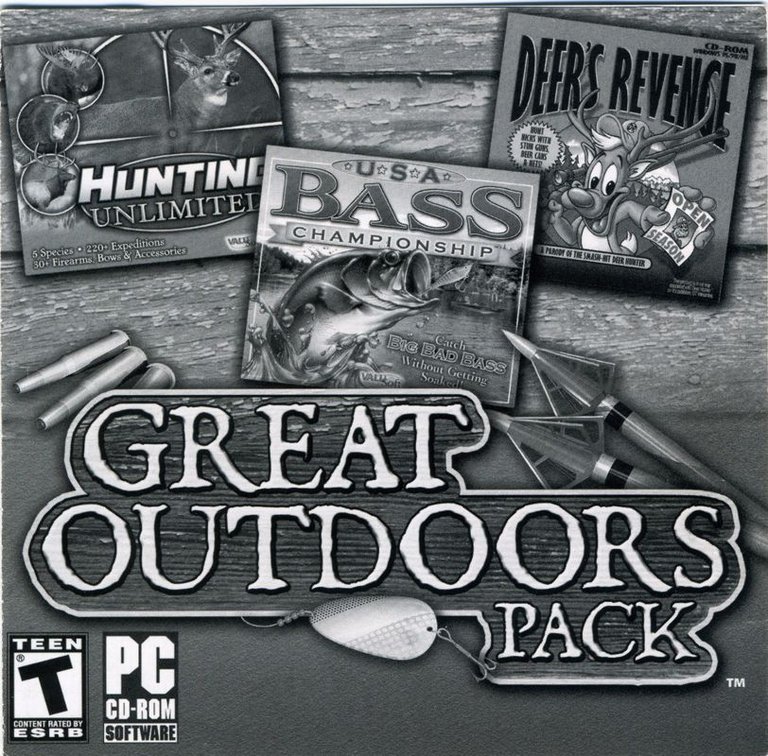

Great Outdoors Pack is a compilation video game released in September 2004 for Windows, featuring three titles—Hunting Unlimited, USA Bass Championship, and Deer’s Revenge—all themed around outdoor sportsmanship and hunting. The games offer simulated experiences in hunting and bass fishing, set in various outdoor environments.

Great Outdoors Pack: A Review of a Niche 2004 Compilation

Introduction: A Snapshot of a Specific Genre’s Zeitgeist

In the vast and voracious ecosystem of the video game industry, certain products exist not as landmarks of innovation but as precise thermometers of a specific market’s temperature. Great Outdoors Pack, released by ValuSoft in September 2004 for Windows, is one such artifact. It is a compilation of three titles—Hunting Unlimited, USA Bass Championship, and Deer’s Revenge—united by a theme of outdoor sportsmanship and hunting. To evaluate this collection is to undertake an exercise in historical triangulation: understanding the state of “budget” software distribution in 2004, the perennial appeal (and oft-questioned cultural place) of hunting/fishing simulations, and the very nature of the compilation as a business and preservation model. My thesis is that while Great Outdoors Pack offers negligible value as a cohesive artistic or mechanical experience, it serves as a crucial, if unglamorous, data point in the study of early-2000s value publishing and the niche simulation genre. Its significance lies entirely in its context, not its content.

Development History & Context: The World of Value Publishing

The early-to-mid 2000s was the golden age of the retail software compilation, particularly in the PC space. Publishers like ValuSoft, Activision Value, and Encore operated on a straightforward model: acquire the rights to older, often mid-tier or niche titles (or develop simple new ones), bundle them under a catchy, genre-specific title, and sell them via big-box retailers, mail-order catalogs, and later, early digital storefronts for a low price point (typically $9.99-$19.99). These packs targeted casual gamers, gift-givers, and those exploring a new hobby simulation on a budget.

Great Outdoors Pack is a pure product of this ecosystem. Its listed developers are a mosaic of small, specialized studios: Digital Content LLC, SCS Software, Snarfblat Software, and Sunstorm Interactive, Inc. These were not household names but workhorses of the value segment, often recycling engines and mechanics across multiple hunting, fishing, and “outdoor” titles. The technological constraints were those of the late-1990s/early-2000s: build-for-Windows 98/ME/2000/XP, CD-ROM media, simple 3D hardware acceleration (if any), and low system requirements to maximize install bases. There was no singular “creator’s vision” here; the vision was purely commercial: to create a shelf-friendly product that appealed to an outdoors enthusiast who might recognize the names of the included activities but not the individual games.

The gaming landscape of 2004, as documented by the Wikipedia overview, was dominated by seismic releases: Half-Life 2, Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, Halo 2, Metal Gear Solid 3, and the launch of the Nintendo DS. These were AAA spectacles. Great Outdoors Pack existed in a parallel universe, catering to a completely different audience with a different value proposition. It was a product of the “long tail,” sold alongside the latest blockbusters but in a separate, lower-margin aisle.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Absence of Story in the Pursuit

Compilations of this nature are fundamentally acinematic; they do not possess a narrative in the traditional sense. There is no overarching plot, no character arc, and no thematic dialogue between the three included titles. Instead, the “narrative” is the player’s own simulated experience, and the “theme” is a specific, somewhat controversial strand of American cultural mythology: the individual’s mastery over the natural world.

Each component game explores a facet of this:

1. Hunting Unlimited: Presumably focuses on the stalking, tracking, and harvesting of various North American game animals. The implied narrative is one of patience, skill, and ultimately, conquest. The theme is the ethical (or at least simulated) hunter, respecting the animal’s vitality while claiming it as a trophy.

2. USA Bass Championship: This shifts to a competitive sport. The “story” is the player’s ascent through bass fishing tournaments. The theme here is technical mastery—understanding lures, water conditions, and fish behavior to out-compete virtual opponents.

3. Deer’s Revenge: This title is the most intriguing and thematically distinct. Without sources detailing its mechanics, its name suggests a possible twist: perhaps playing as the deer, evading hunters, or a more action-oriented take on the genre. If so, it subverts the theme slightly, introducing a “prey’s perspective” narrative of survival against human predation. However, given its likely origin in the same stable as the other two, it’s more probable it’s another hunting simulation, with “Revenge” being a hyperbolic subtitle.

The collective thematic statement is one of outdoor sportsmanship—a term that sanitizes hunting and focuses on the skills, gear, and idealized communion with nature. It avoids the visceral reality of the act, presenting a clean, digital proxy. There is no commentary on conservation ethics (beyond perhaps in-game regulations), no exploration of the land’s history, and no depth to the animal AI beyond behavioral triggers for the player’s benefit. The narrative is a skin applied to game systems, not an end in itself.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Three Disconnected Loops

The core gameplay experience is defined by the jarring switch between three distinct simulation sub-genres, each with its own interface, controls, and goals. There is no integration.

1. Hunting Unlimited & Deer’s Revenge (Presumed Similar):

* Core Loop: Locate a zone -> observe animal signs (tracks, scat) -> identify and stalk prey -> aim and shoot (or use a bow) -> track wounded animal -> harvest.

* Systems: Likely includes weapon selection, optic choices (scopes), wind direction indicators, time-of-day and weather effects on animal movement, and a scoring system based on animal size/antler points. “Sportsmanship” might be enforced through rules against shooting from vehicles or certain times of day.

* Innovation/Flaws: These sims were known for their detailed (for the time) animal AI and large, albeit often sparsely populated, environments. Flaws typically included clunky interfaces, unrealistic animal pathfinding, and a “spot-the-pixel” quality to hunting where success felt more like finding a spawn point than true tracking. The compilation format means any progress or unlocks are isolated to each game.

2. USA Bass Championship:

* Core Loop: Select a lake/time -> cast line -> choose lure/bait based on depth/cover -> wait for bite -> set hook and reel in -> measure and weigh catch -> compete in tournament rankings.

* Systems: Realistic (for the era) fish behavior models, depth charts, weather/barometric pressure effects, a wide array of artificial lures and rigs. Tournament modes with time limits and weight-based scoring.

* Innovation/Flaws: The innovation was in the depth of the fishing “meta-game”—the knowledge required. Flaws often involved repetitive gameplay, simplistic underwater visuals, and a lack of true physicality in the casting/reeling mechanics compared to later titles.

Compilation-Wide Issues: The switch between these modes is seamless but disorienting. A player in the serene, patient mindset of fishing is thrust into the high-adrenaline stalk of a deer hunt. The UI paradigms clash. There is no unified progression, meta-game, or framework (like a “career” mode spanning all activities) to justify the compilation’s existence beyond shelf presence. It’s three separate software products sharing a single jewel case and a thematic label.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetic of the Budget Sim

The artistic and audio design is a direct function of its budget and technological constraints. These are not games that aim for immersion through realism but through familiarity and functionality.

- World-Building/Visuals: Environments are constructed from low-polygon 3D models with low-resolution textures. Forests are collections of repeating tree assets; lakes are flat planes with reflective surfaces; terrains are simple height maps. The sense of place is generic “North American wilderness.” There is no unique identity to any location; a forest in Hunting Unlimited could easily be a forest in Deer’s Revenge. The world-building is purely ludic—spaces exist to facilitate the hunting/fishing mechanics, not to be explored or narrativized.

- Art Direction: Utterly utilitarian. The focus is on clear visibility of animals/fish and recognizable landmarks. There is no stylistic cohesion between the games. The hunting titles are drab, earth-toned, and serious. The fishing title might have slightly brighter colors but remains muted. Character models (the player avatar, if present) are minimal or non-existent, viewed from first-person.

- Sound Design: A critical component for these sims, and here it is a mixed bag. Ambient nature sound loops (bird calls, wind, water) are essential for atmosphere but are often repetitive and low-fidelity. The sound of a bowstring, a gunshot, or a reel’s click is functional. Animal sounds are used as audio cues (a turkey gobble, a grunting deer). The music, if any, is typically absent or consists of bland, royalty-free country/folk-inspired tracks during menus. The soundscape prioritizes gameplay information (a fish biting, an animal alert call) over artistic composition.

Collectively, the presentation screams “budware.” It is the visual and auditory equivalent of a stock photo: competent, recognizable, and utterly devoid of artistic intent or memorable quality. The compilation offers no visual or auditory through-line to bind the experiences.

Reception & Legacy: A Product of Its Time, For Its Time

Critical reception for such compilations was virtually non-existent in the mainstream press. Specialist hunting/fishing simulation magazines or websites might have reviewed the individual titles upon their original release, but the compilation itself was rarely seen as a newsworthy entity. Its “reputation” is defined by its commercial strategy, not its quality.

In the context of 2004, it was a drop in an ocean of value-pack software. The Wikipedia data shows the year’s best-sellers were the aforementioned AAA titans. Great Outdoors Pack‘s sales would have been steady, unspectacular, and likely driven by placement in the “sports” or “outdoor” sections of retailers like Walmart or Circuit City. It was purchased by a specific demographic: perhaps an older enthusiast of the outdoors, a parent buying a “safe” (ESRB Teen for “Blood, Comic Mischief, Use of Alcohol and Tobacco, Violence”) game for a child interested in hunting, or a bargain bin browser.

Its legacy is as a historical footnote in several areas:

1. Value Publishing Model: It exemplifies the pre-Steam “shovelware” compilation model that kept countless niche PC simulation titles in print and available to a broad audience. It was a bridge between hardcore sims and casual curiosity.

2. Genre Preservation: While the individual games within may be forgettable, the compilation serves as a time capsule for the aesthetics, mechanics, and interface design of early-2000s hunting/fishing sims. For historians, it’s a primary source.

3. The Compilation Format: It highlights the ultimate weakness of the un-themed compilation—a lack of synergy. Compare it to the Outdoor Action Pack (2001) mentioned in the auxiliary source, which bundled Cabela’s titles with Ultimate Paintbrawl 3. The disconnect between hunting and paintball is similar. The most successful compilations (The Orange Box, Myst collection) had strong narrative or mechanical through-lines. Great Outdoors Pack has only a superficial thematic one.

4. Cultural Artifact: It represents a very specific, largely apolitical, view of the American outdoors—focused on individual sport hunting and fishing, devoid of deeper ecological or indigenous contexts. It’s a product of a particular marketing perception of the “outdoor lifestyle.”

Conclusion: The Definitive Verdict

Great Outdoors Pack is not a “good” game by any conventional metric of game design, artistic merit, or technical achievement. It is a disjointed, low-fidelity collection of three dated simulations. To play it is to engage with the shadow of the early-2000s value software market. Its components are artifacts of their respective sub-genres, each representing a specific understanding of what constituted “fun” in a hunting or fishing sim at the time: patient observation, technical gear knowledge, and a clean, gamified kill/harvest.

Its place in video game history is secure, but it is a place in the footnotes. It is a testament to the industry’s ability to serve ultra-specific niches through low-cost, high-volume retail bundles. It is a direct ancestor to today’s “budget bundles” on Steam and the ” shovelware” sections of digital consoles. For the vast majority of players, it is an object of curiosity or nostalgia at best. For the historian, it is a perfectly preserved specimen of a bygone business practice and a genre’s aesthetic constraints. Its ultimate value is not in the play, but in the study—a clear, unpretentious window into a quieter, more compartmentalized corner of the 2004 gaming landscape, existing far from the spotlight of Half-Life 2 and San Andreas, but serving its audience with a quiet, persistent reliability.