- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: iPad, iPhone, Macintosh, Windows, Xbox 360

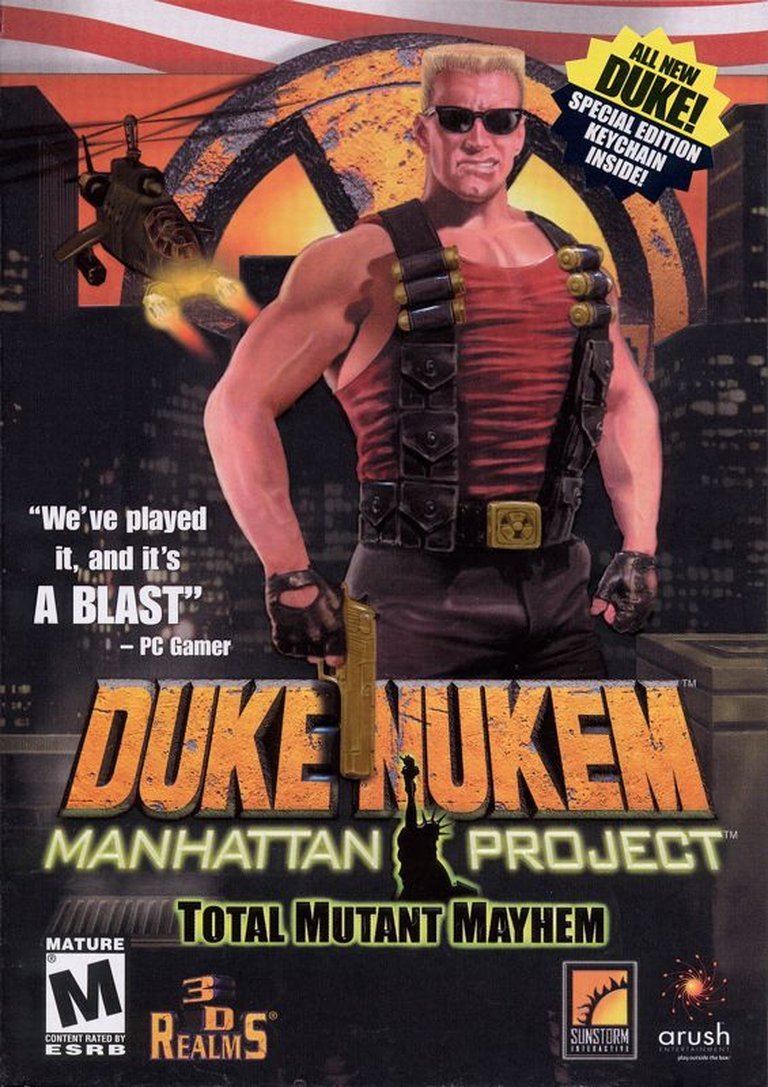

- Publisher: 1C Company, 2K Games, Inc., 3D Realms Entertainment, Inc., Apogee Software, LLC, ARUSH Entertainment, Gearbox Publishing, LLC, Gearbox Software LLC, HD Interactive B.V., Interceptor Entertainment ApS, Spawn Studios, Lda, Ubi Soft Entertainment Software

- Developer: Sunstorm Interactive, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Double jump, Jetpack, Platform, Puzzle elements, Shooter

- Setting: City – New York

- Average Score: 78/100

Description

Duke Nukem: Manhattan Project is a third-person platform shooter set in New York City, where the iconic hero must thwart the villainous Mech Morphix and his mutagenic GLOPP slime. Across eight elaborate stages—from skyscraper rooftops to gritty subway stations—Duke battles a horde of mutants, defuses bombs strapped to captured women, and employs a diverse arsenal of weapons, all while spouting his trademark sarcastic one-liners in a blend of action and puzzle-solving gameplay.

Gameplay Videos

Duke Nukem: Manhattan Project Free Download

Duke Nukem: Manhattan Project Guides & Walkthroughs

Duke Nukem: Manhattan Project Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (78/100): It’s nice to see Duke again, and even nicer to have a great modern platform game.

gamepressure.com (76/100): A side-step ahead of Duke Nukem Forever. Manhattan Project was a great spin-off of Duke’s adventures

Duke Nukem: Manhattan Project Cheats & Codes

PC

Press ~ to open console. Enter cheat codes directly or type ‘exec cheats.cfg’ to enable key-based cheats and press keys during gameplay.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| toggle g_p_god | God mode |

| toggle r_stats | Game statistics |

| toggle g_debug | Debug mode |

| toggle g_map_info | Map information |

| give all | All weapons and items |

| give ammo | Maximum ammunition |

| give jetpack | Jet pack |

| give forcefield | Force field |

| give keys | All keys |

| give nuke | 10 nukes |

| give life | Extra life |

| give secret | Mark secret found |

| give bomb | Spawn extra babe |

| kill | Suicide |

| pause | Matrix-style pause |

| camera camera | Camera can explore level |

| camera player | Return camera to normal |

| toggle r_timings | View frame rate |

| give health | 100 Ego |

| give kill | Mark a kill (specify number) |

| map eXXpYY_aZZ | Teleport to specified level (e.g., e01p02_a03) |

| G | All weapons and items except jetpack and forcefield |

| H | All ammunition |

| J | Jet pack |

| F | Force field |

| L | Extra life |

| K | Suicide |

| I | God mode |

| P | Matrix-style pause |

| M | Display map name |

| – | Small HUD |

| = | Normal HUD |

Duke Nukem: Manhattan Project: A Comprehensive Review

Introduction: The King in a Strange New Kingdom

In the pantheon of video game icons, few figures are as simultaneously revered and reviled as Duke Nukem. A creation of the early ’90s shareware boom, Duke’s evolution from a cheeky, side-scrolling action hero into a brash, polygon-rendering paradigm of ’90s shooter excess with Duke Nukem 3D cemented his legend—and his infamous reputation. By 2002, the gaming world was locked in a collective, years-long stare at the empty chair marked “Duke Nukem Forever,” the vaporware project that defined development hell. Into this void stepped an unlikely savior: Duke Nukem: Manhattan Project, a budget-priced return to Duke’s platformer roots, but with a shiny, fully 3D engine. This review posits that Manhattan Project is not merely a nostalgic curiosity or a cheap cash-in, but a fascinating, flawed, and ultimately successful experiment. It captures the irreverent soul of the Duke franchise while grafting it onto a nearly extinct genre, creating a product that is chronologically and mechanically caught between eras. Its legacy is one of respectful homage, technological cleverness, and commercial obscurity, making it a quintessential “what if” in the Duke timeline.

Development History & Context: A Budget Rescue Mission

The studio behind Manhattan Project was Sunstorm Interactive, a developer known for hunting and simulation titles like the Bird Hunter series, not for action-platformers. The project was produced under license by the legendary 3D Realms, the stewards of the Duke franchise, and published by Arush Entertainment, a company specializing in budget and value-priced titles. This trifecta immediately signals the game’s positioning: a lower-cost, lower-risk project intended to satiate fans starved for new Duke content while the interminable Duke Nukem Forever languished in development.

The technological heart of the game was the Prism3D engine. This was a critical choice. While the gameplay is strictly 2.5D—Duke moves on a fixed plane—the world is rendered in full 3D polygons. This allowed for dynamic camera work: angles could shift from side-view to isometric or dramatic low angles during key moments, and players could zoom in and out. This was not the sprite-based charm of Duke Nukem 1 & 2 or the Build engine’s clever 2.5D of Duke 3D. It was a genuine, if constrained, 3D world, giving the game a sleek, modern (for 2002) look that belied its classic gameplay. The choice reflects a pragmatic compromise: use accessible, modern 3D technology to revitalize a 2D genre that had largely faded from the PC mainstream.

Crucially, the project’s origin story is one of repurposing. Trivia from the source material reveals that Arush initially planned a remake of the original Duke Nukem with the enemy Dr. Proton. This was changed to the new villain, Mech Morphix, likely to avoid narrative clashes with the planned Duke Nukem Forever. This pivot from direct remake to original side-story set within the existing universe allowed the game to stand on its own while still feeding the primary franchise’s ecosystem.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: GLOPP, Greed, and Gumption

The plot of Manhattan Project is pure, concentrated Duke Nukem escapism. A power-hungry mad scientist, Mech Morphix, has flooded New York City with G.L.O.P.P. (Gluon Liquid Omega-Phased Plasma), a radioactive slime that mutates innocent creatures and citizens into monsters. His ultimate plan involves strapping GLOPP bombs to kidnapped women (“babes”) and detonating them to spread the mutation chaos. Duke, ever the patriot and hero-for-hire, is contracted to stop him. The narrative is delivered through the game’s eight distinct chapters (Rooftop Rebellion, Chinatown Chiller, etc.), each with three parts, culminating in a boss fight.

Thematically, the game is a deep dive into the established Duke lexicon. It is a celebration of hyper-masculine, consequence-free violence wrapped in layers of self-aware, referential humor. Morphix is a direct echo of Dr. Proton from the original Duke Nukem, reinforcing the series’ cyclical battle against mad science. The enemies are a bestiary of American pop-culture mutations: Uzi-wielding alligators (Gator-Oids), giant man-eating cockroaches (Ratoids), and the series staple Pig-Cops. The introduction of the Fem-Mech—a whip-wielding, somersaulting female gynoid—is a controversial addition that leans into the franchise’s problematic objectification and BDSM-tinged villainy.

Duke’s dialogue, voiced as always by the iconic Jon St. John, is the narrative’s core vehicle. It’s a relentless stream of one-liners that parody action movie clichés (“Say hello to my little friend!”), mock the enemies (“I hate pigs!”), and break the fourth wall. The game’s humor is aggressively contemporaneous, with references to The Matrix (“Follow the White Rabbit”), Broadway’s Cats, and even the classic arcade game Frogger (“What am I, a frog?”). The story’s simplicity—”go here, fight this, save that”—is not a flaw but a feature, a deliberate return to the objective-driven purity of 16-bit platformers. The true “theme” is Duke’s unshakeable, anarchic id, a force of nature cleaning up a mess with maximum carnage and minimal introspection.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Precision Mayhem in 2.5D

Manhattan Project’s genius lies in its mechanical synthesis. It takes the tight, responsive platforming of classics like Mega Man or Contra and injects it with the arsenal and attitude of the Duke Nukem 3D era.

Core Loop & Structure: The game is divided into 8 chapters x 3 stages. Each stage’s objective is triconical: 1) Rescue the “babe” by defusing her GLOPP bomb, 2) Find the colored keycard to unlock the exit, 3) Survive the onslaught of enemies and environmental hazards. This creates a clear, satisfying progression loop. The save system is generous by old-school standards, allowing saves anywhere, which mitigates the frustration of the genre’s infamous difficulty spikes.

Movement & Platforming: Duke controls with weight and precision. The standard move-set includes run, crouch, jump (with a crucial double-jump for height and distance), a powerful slide-kick, and the signature Mighty Boot melee attack. A ledge-grab mechanic allows for recovery, a modern touch that prevents unfair deaths. The 2.5D presentation means movement is locked to the plane, but the shifting camera angles (from tight side-views to dramatic overhead perspectives during hazards) create a dynamic feel, as if the player is being directed by a cinematic cameraman. This is the Prism3D engine’s primary gameplay contribution.

Combat & Arsenal: The weapon wheel includes nine tools of destruction. The starting Golden Eagle pistol is weak but ammo-rich. The Shotgun and Assault Rifle (sharing ammo, a quirk noted in reviews) are workhorses. The Pipebomb is a classic, with a dedicated quick-throw button. The Rocket Launcher (PRPG) is devastating but uses precious Pipebombs. Two unique weapons define the strategy: the GLOPP Ray, which de-mutates enemies, turning them back into harmless, kickable creatures; and the ultimate prize, the X-3000 Pulse Cannon, a screen-clearing lightning gun unlocked only by a perfect Nuke collection on Hard difficulty. Combat is fast, requiring tactical use of space, weapon switching, and the environment (e.g., kicking enemies into pits).

Progression & Secrets: The Nuke System: The central meta-game is collecting 10 hidden Nukes per stage. These are often tucked into destructible walls, secret rooms, or perilous heights. Collecting all 10 in a stage permanently increases Duke’s maximum EGO (health) and ammo capacity. Collecting all 80 Nukes across difficulties unlocks the X-3000 and cosmetic rewards (like a blue shirt). This system brilliantly encourages exploration and replayability, rewarding mastery and curiosity. It’s a “collectible” system that directly and meaningfully enhances combat efficacy.

The EGO Meter: A clever rebranding of the health bar. Duke’s ego is his life force. It regenerates slowly if above a threshold but can be quickly depleted by damage. Picking up health items and killing enemies (with a bonus for kick/kill) refills it. This system ties aggression to survival, reinforcing Duke’s “kick first, ask questions later” ethos.

UI & Flaws: The HUD is clean and functional. However, the game inherits some genre-era flaws: repetitive enemy death animations, occasional hit-detection issues (as noted by reviewers), and a boss design that can be either frustratingly cheap (like the helicopter chase) or trivial. The camera, while dynamic, can occasionally obscure pits or hazards during its cinematic shifts.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Polygonal New York

The art direction is a standout achievement for a budget title. Using Prism3D, Sunstorm created a vibrant, detailed 2.5D New York. The eight chapters offer remarkable visual variety: the rain-slicked, neon-drenched rooftops of Rooftop Rebellion; the claustrophobic, graffiti-covered tunnels of Metro Madness; the industrial churn of Fearsome Factory; and the sterile, futuristic corridors of Orbital Oblivion. The character models, especially Duke’s blocky, muscular physique and the grotesque mutant designs, are full of personality. The Fem-Mechs and the grotesque, multi-eyed bosses are particularly memorable.

The sound design is quintessential Duke. Jon St. John’s vocal performance is, as always, the anchor—delivering lines with a perfect blend of smugness, menace, and camp. The weapon sounds are punchy and satisfying, from the boom of the shotgun to the zapping of the Pulse Cannon. The soundtrack is a mix of rock and industrial tracks that underscore the action without ever becoming intrusive. It’s functional, effective, and perfectly in keeping with the game’s tone.

Together, the visuals and sound create an atmosphere that is both gritty and cartoonish. It’s a comic book vision of New York under siege, where blood splatters on brick walls and giant cockroaches lurk in subway shadows. The 3D engine allows for impressive particle effects (explosions, GLOPP slime) and colored lighting that give the 2D plane a surprising sense of depth and life.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Classic in Rights Hell

Upon release in 2002, Manhattan Project received a generally favorable critical reception, with aggregate scores around 72-76% on PC. Reviews consistently praised its fun factor, faithfulness to the Duke spirit, clever use of the 3D engine, and level design. Common criticisms included its relatively short length (4-8 hours), repetitive elements in later sewer levels, occasional technical bugs, and underwhelming boss fights.

Commercially, it was a budget title ($24.99 in the US) and did not set the world on fire. Its legacy is inextricably linked to the shadow of Duke Nukem Forever. For fans enduring that game’s endless delays, Manhattan Project was a much-appreciated, quality stopgap. It proved the Duke formula could work in a different format.

However, the game’s post-launch life became mired in legal complications. Its developer, Arush Entertainment, was bought out by HIP Interactive, which went bankrupt. As detailed by 3D Realms’ Joe Siegler, the game’s rights became entangled in bankruptcy proceedings held by a court-appointed firm, unreachable by 3D Realms. This “rights hell” effectively removed the game from digital storefronts for years, turning it into a rare physical commodity. Its reappearance on platforms like GOG.com (in the 3D Realms Anthology) and the Xbox 360 Marketplace (2010) was a cause for celebration among preservationists.

Its influence on the industry is minimal; it did not spark a revival of 2D platformers on PC. Its true legacy is as a curated artifact. It serves as a proof-of-concept for how to modernize a classic genre without losing its soul, a lesson seen later in games like Shadow Complex (2009). It is also a testament to the enduring, adaptable power of the Duke Nukem character—he could be dropped into a polygonal, chapter-based platformer and still feel unmistakably like himself.

On modern platforms, its reception diverged sharply. The PC version’s legacy holds (Metacritic 78), but the Xbox 360 port (2010) was critically panned (Metacritic 41). Critics cited dated visuals, poor controls (notably the inability to fire downward), repetitive design, and a lack of value compared to modern XBLA titles. This stark contrast highlights how the game’s niche appeal is deeply tied to its original context as a nostalgic PC budget title.

Conclusion: Flawed, Fun, and Fundamentally Duke

Duke Nukem: Manhattan Project is not a forgotten masterpiece, nor is it a disposable cash-grab. It is a competent, charming, and deeply authentic side-quest in the Duke saga. Its strengths—the creative level design, the fantastic weapon arsenal (especially the strategic Glopp Ray and the glorious X-3000), the endlessly quotable Duke dialogue, and the smart use of a 3D engine to enhance 2D platforming—outweigh its weaknesses: the occasionally flat art in later stages, the rudimentary boss fights, the short runtime, and the technical bugs that plagued some users.

It captures a specific moment in time: the last gasp of the serious PC platformer, the agonizing wait for Duke Nukem Forever, and the final era where a major franchise could reliably release a $25 budget-title spin-off with genuine love for its source material. Its entanglement in rights hell only adds to its mythos—a game that fans had to fight to preserve.

Historically, it sits as the last “pure” Duke Nukem game before the franchise’s turbulent 2010s. It makes no apologies for its premise, its hero, or its genre. In that, it is perhaps the most Duke Nukem game ever made—a brash, confident, slightly crude, and undeniably fun experience that knows exactly what it is and delivers on that promise with a smirk. For historians, it’s a crucial bridge between Duke’s 2D origins and his 3D future. For players, it remains a delightful, bite-sized chunk of ass-kicking, babes-saving, one-liner-spouting bliss. Hail to the King, indeed.