- Release Year: 1990

- Platforms: DOS, Macintosh, PC-98, Sharp X68000, Windows

- Publisher: Electronic Arts, Inc., ORIGIN Systems, Inc., Pony Canyon, Inc.

- Developer: ORIGIN Systems, Inc.

- Genre: Role-playing, RPG

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Crafting, Exploration, Fishing, Open World, Party management, Survival cooking, Turn-based combat

- Setting: Dinosaurs, Prehistoric, Tribal

- Average Score: 100/100

Description

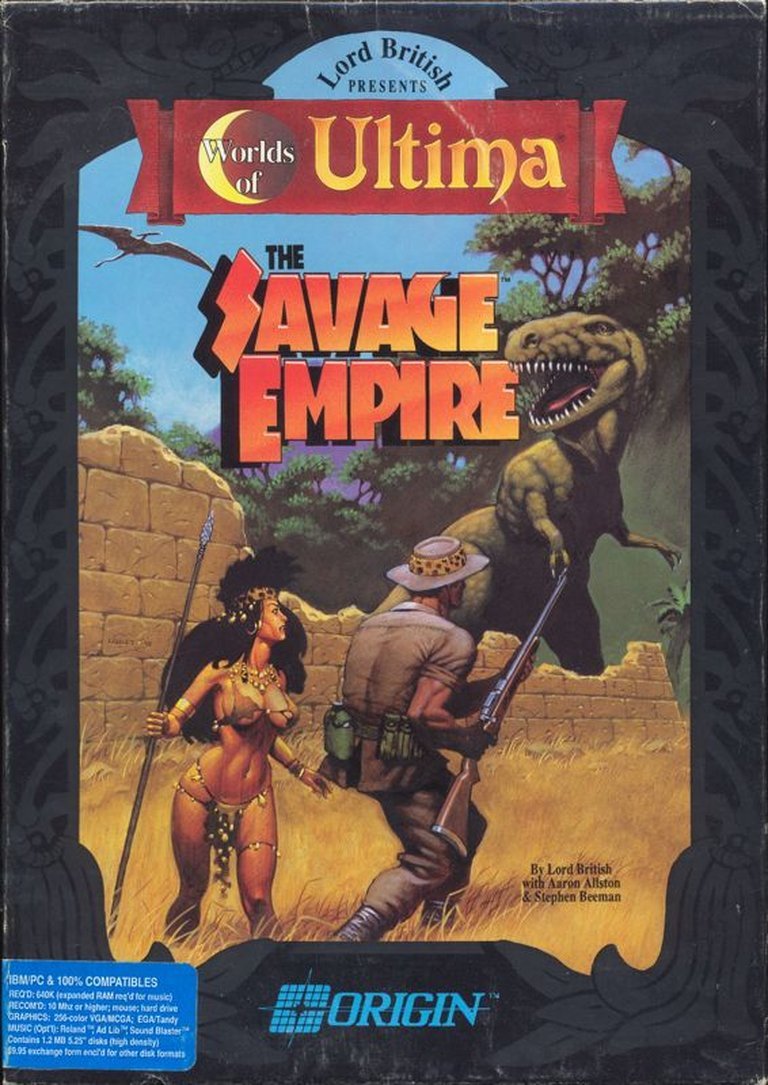

Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire is a role-playing game spin-off from the Ultima series, where the Avatar is transported from Britannia to the prehistoric Valley of Eodon following a magical experiment. There, he must navigate a world populated by Mesoamerican and African-inspired tribes, Neanderthals, dinosaurs, and sentient reptiles and insects, rescue his companion Aiela from abduction, and unite the warring factions against the invasive Myrmidex giant ants, all through exploration, turn-based combat, and interactive puzzle-solving in a seamless open world built on the Ultima VI engine.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire

PC

Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire Free Download

Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire Guides & Walkthroughs

Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org (100/100): The game involves numerous quests, puzzles and battles that will enthrall you. It also involves 50+ hours of playing time!

Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire Cheats & Codes

PC

Activate cheat codes by pressing the specified key combinations during gameplay. Alt-cheats require the MDHack program to be installed and running under DOSBox for functionality.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| ALT-X | During combat on enemy’s turn, makes enemy disappear, ends battle with ‘The Gods Intervene’ message, and prevents loss of experience points or treasure. |

| [Alt]+213 | Provides instant area overview like the Eagle Eye spell, displays current time of day and party coordinates (x/y/z). |

| [Alt]+214 | Opens a prompt to enter hexadecimal x/y/z-coordinates for teleporting the party to a specific location. |

| [Alt]+215 | Advances game time by one hour. |

| [Alt]+222 | Toggles ethereal mode, allowing the party to walk through obstacles like trees, doors, and walls. |

| [Alt]+224 | Opens a prompt to enter an NPC value (hexadecimal) to teleport the party to that NPC. |

| [Alt]+232 | Displays the portrait of an NPC based on the entered value. |

| [Alt]+242 | Opens an NPC editing tool to manipulate flags after entering the NPC’s numeric value. |

Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire: A Pulp-Adventure Bridge in the Ultima Saga

Introduction: The Avatar Ventures Into the Pulp Magazine

In the pantheon of classic computer role-playing games, few series carry the weight of history and innovation as the Ultima saga. By 1990, Origin Systems’ magnum opus had already redefined narrative depth, player agency, and moral complexity in the genre. Yet, that same year, a curious side-story emerged from the same engine bay: Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire. It dispatched the Avatar, the renowned hero of Britannia, not to another realm of high fantasy, but to a prehistoric “lost world” teeming with dinosaurs, disparate tribal cultures, and giant ants—a setting售退 right out of a 1930s Amazing Stories pulp cover. This was not another chapter in the Britannian virtue quests; it was a deliberate, almost defiant, pivot toward B-movie adventure. This review argues that The Savage Empire is a fascinating, deeply flawed, and historically significant game: a technically proficient but conceptually uneven bridge between the ambitious role-playing of Ultima VI and the more action-adventure, narrative-focused experiments that would follow, including its own sequel, Martian Dreams. Its legacy is one of creative ambition hamstrung by tonal inconsistency and a failure to fully divorce itself from the Ultima brand’s escalating expectations, even as it pioneered important interface and cutscene techniques.

Development History & Context: Reusing the Crown Jewels

The game emerged from a specific set of economic and technological circumstances at Origin Systems. Following the monumental success of Ultima VI: The False Prophet (1990), Origin possessed a state-of-the-art, highly flexible isometric game engine and, crucially, a full suite of world-building tools. As noted in contemporary sources and credits, the team saw an opportunity to amortize this development cost by creating additional, standalone games using the same core technology. The ”Worlds of Ultima” banner was born, conceptualized as a series of ”side-quests” for the Avatar, enabled by the black moonstone artifact from Ultima VI. This device allowed for travel to ”anywhere in space and time,” providing a convenient narrative MacGuffin to explore genres outside high fantasy.

The development team, led by Director Siobhan Beeman and Writer Aaron Allston, was a mix of Ultima veterans and new voices. The project’s credo seems to have been: Leverage the unparalleled interactivity and seamless world of the Ultima VI engine, but strip back the dense RPG mechanics and virtue-based morality to create a more accessible, action-oriented adventure. This was a conscious shift in target audience. As one player review succinctly states, the Worlds of Ultima series was ”more aimed towards new RPG players.” Technologically, the game pushed the Ultima VI engine further by integrating the Origin FX cutscene system (famously used in Wing Commander) for key story moments—the first time the series used in-engine cinematics so extensively. However, the core technological constraint was clear: the world of Eodon, while visually distinct with its jungle tileset, was fundamentally a reskinned Britannia, sharing the same underlying data structures and interaction paradigms. This reuse was a pragmatic masterstroke for rapid development but also a creative cage.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Pulp Reverie and Moral Simplification

The plot of Savage Empire is unabashedly pulp. Following a moonstone experiment mishap with Dr. Rafkin (the curator from Ultima VI) and reporter Jimmy Malone, the Avatar is stranded in the Valley of Eodon—a hidden, jungle-filled valley on Earth where tribes from disparate eras (Mesoamerican, African, Neanderthal) and species (Sakkhra reptilians, giant insects) coexist. The central conflict is an invasion by the ant-like Myrmidex, which forces theAvatar to unite the squabbling tribes into an alliance. Each tribe demands a specific task—defeat a T-Rex, recover a holy statue, retrieve a sacred artifact—before they’ll join.

Thematically, the game attempts a morality tale about tribalism and unity against a common threat, echoing the anti-xenophobia of Ultima VI but in a starkly simplified, colonialist framework. The player is an obvious outsider (a white, Earth-born hero) who must ”civilize” the fractious natives into a coherent fighting force. This is where the narrative’s greatest weaknesses surface. As Dennis Owens noted in his seminal Computer Gaming World review, the game presents a ”disturbing view of a possible trend in the Ultima line: caricature.” The tribes, while visually and nominally diverse, function as interchangeable quest-givers. Their cultures are shallow backdrop, reduced to a chief and shaman who give the same ”join us” quest. The profound philosophical engagement with ethics and society that defined Ultima IV-VI is absent. The ”virtues” play ”no part whatsoever,” as one reviewer observed, replaced by a simple ”unite the factions” objective. The story’s only real twist is the reveal that the valley itself, and the tribes’ displacement, is the result of a corrupted moonstone—a neat, if predictable, explanation that ties back to the Ultima VI artifact without meaningful thematic resonance.

Characterization is equally thin. Aiela, the Kurak chieftain’s daughter, is a classic ”damsel in distress” and potential romance interest, existing primarily to motivate the hero. The Three Stooges’ cameo as members of the Disquiqui tribe is a jarring, purely humorous insertion that epitomizes the game’s unsure tone—is this a serious fable about prejudice or a goofy jungle romp? The narrative is a enjoyable but lightweight pulp pastiche, a far cry from the layered, player-determined morality tales of the main series.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Interactivity Preserved, Depth Sacrificed

The Savage Empire is mechanically Ultima VI with a lost-world skin. The isometric, real-time-with-pause combat, seamless open world, and foundational ”use anything on anything” interactivity are all intact and are the game’s greatest strengths. The crafting and alchemy systems are particularly praised. Players can realistically combine resources: gathering sulphur, charcoal, and saltpeter to make gunpowder; weaving flax from Yucca plants into cloth, tarring it, and making torches. This systemic interactivity is the true heir to the Ultima legacy here. The world, while smaller than Britannia, feels dense and playable.

However, every other RPG pillar is deliberately simplified for accessibility. Character progression is almost negligible. The Avatar starts at Level 6, companion Triolo at Level 7, with a hard cap of 8. This eliminates the traditional grind, focusing the game on puzzle-solving and questing over combat leveling. The spell system is drastically pared down to nine spells, all available from the start, using ”totems” as reagents with no mana limit. This removes resource management and strategic spell choice, reducing magic to a toolbox of utility effects (heal all/cleanse poison, light, etc.).

Companion use is restricted: only one non-Avatar character (typically Dr. Rafkin or another specialist) can cast spells, and only with specific totems. The party size limit of four (expandable to seven via story events) is standard, but the lack of meaningful leveling makes most NPCs static tools rather than developed allies. The interface, while familiar, shows signs of ”dumbing down.” Command feedback is less descriptive (a torch is ”used,” not ”ignited”), and the groundbreaking free-form dialogue of Ultima VI is replaced by a more structured, less dynamic system where only key NPCs (chiefs, shamans) have unique conversation trees; generic tribe members spout the same lines. This transforms the vibrant world of Ultima VI into a more formulaic hub-and-quest structure: visit village, talk to chief, complete task, repeat.

This simplification is the game’s central design thesis. It prioritizes clear, solvable puzzles (”put a bell on a T-Rex” being a famous example) and exploration over complex RPG systems. For its intended audience—newcomers to the genre—this works. For series veterans, it feels like a stripped-down model. The review from Power Play magazine captures this dichotomy perfectly: it’s a ”gelungene Abweichlung” (successful variation) for Ultima fans, but its reliance on the Ultima name may have confused newcomers expecting a different experience.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Distinctive, if Homogeneous, Pulp Veneer

The Valley of Eodon is a visually cohesive and thematically appropriate setting. Using a completely new tileset, Origin’s artists crafted a jungle world filled with lush greenery, muddy rivers, volcanic areas, and tribal villages. The palette is warmer and more earthen than Britannia’s fantasy hues. While the technical fidelity is identical to Ultima VI (16-color EGA, later 256-color VGA in ports), the artistic direction is consistent and immersive. The ”seamless world” philosophy means no loading screens between overworld, villages, and dungeons, preserving the sense of a contiguous, explorable space.

The sound design is a standout. Composer George Sanger (”The Fat Man”) delivered a moody, percussive, and atmospheric soundtrack that avoids fantasy orchestration for ethnic-inspired rhythms and ambient jungle sounds. It perfectly underscores the pulp adventure vibe and is often cited as one of the game’s most memorable elements. The use of the Origin FX engine for cinematic introductions and key plot scenes was a significant technical leap for the series, adding dramatic weight to story moments that previously relied on text.

However, this world suffers from a critical homogeneity. The ”dozen tribes” are primarily differentiated by color and minor architectural details in their villages. Their cultures are not deeply realized; they are functional factions serving the ”unite the tribes” plot. This lack of cultural specificity—turning Mesoamerican, African, and neanderthal societies into generic ”tribal” archetypes—is a major thematic failing. It turns what could have been an exploration of multicultural synthesis into a simplistic ”help the primitives” exercise. The world feels like a theme park of prehistoric tropes rather than a believable ecosystem of displaced peoples.

Reception & Legacy: Critical Praise, Commercial Indifference, and a Stain on the Ultima Name

Reception in 1990-91 was mixed but generally positive from the Ultima-focused press. ACE magazine’s astonishing 96% score lauded its fascination over fighting gargoyles and the variety of tribal social structures. Computer Gaming World‘s Dennis Owens offered the most nuanced take, praising its ”dazzling and successful” qualities against lesser peers but warning of a trend toward ”caricature” within the Ultima line itself. Game Player’s magazine awarded it ”Best PC Fantasy Role-Playing Game” of 1990, praising its graphics and interface for evoking pulp magazine tales. Less forgiving was ASM, which criticized the single save game slot, and Computist, which found it oddly generic.

The commercial reality was stark: it ”didn’t sell too well,” as the player review notes. The reasons are twofold. First, the Ultima name carried heavy expectations for deep RPG mechanics and virtue-based storytelling, which Savage Empire deliberately eschewed. Fans expecting Ultima VII’s complexity were disappointed. Second, as a new IP in all but name, it failed to capture a new audience sufficiently to offset thealienation of core fans. This commercial failure cemented the ”Worlds of Ultima” experiment as a myth—only one sequel (Martian Dreams) was ever made.

Its legacy is therefore bifurcated. Technically and design-wise, it confirmed the Ultima VI engine’s versatility, introduced important cutscene integration, and proved that a high level of environmental interactivity could be the core of a game less focused on combat and leveling. It directly influenced the design philosophy of Martian Dreams, which refined the formula with a stronger narrative and steampunk setting. However, within the Ultima canon, it is often seen as the first clear sign of series fatigue and identity crisis—a game that used the brand’s capital to launch an experiment that the brand’s core audience didn’t want. The later, disastrous departure into action-adventure with Ultima VIII can be seen as a further, more extreme extension of the ”simplify for accessibility” path Savage Empire first trod.

Conclusion: A Flawed but Historic Artifact

Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire is not a great Ultima game. It is not a great RPG by the standards of its own series. Its narrative is a colonialist pulp fantasy with shallow cultural depictions and a predictable ”unite the tribes” structure. Its RPG systems are neutered, its dialogue trees sparse, and its tonal identity hopelessly muddled between serious morality tale and Three Stooges cameo.

Yet, to dismiss it entirely is to ignore its historical importance and its undeniable, if narrow, successes. As a piece of interactive storytelling, it is a masterclass in environmental puzzle design and a testament to the ”use anything” philosophy that made Ultima legendary. As a technical product, it efficiently repurposed a major engine to create a full, new game—a SMART business move that unfortunately confused the market. Its soundtrack and cutscenes elevated its production values above many contemporaries.

Ultimately, The Savage Empire is a fascinating ”what if” and a cautionary tale. What if Origin had fully committed to the ”Worlds of Ultima” as a separate, lighter adventure series, shedding the Ultima name? What if they had invested in deeper cultural world-building for Eodon? As it stands, it is a brilliant game engine in search of a coherent vision, a pulp adventure trapped in the shadow of Britannia’s virtues. It is a worthwhile, flawed artifact—a bridge to nowhere that teaches us as much about the constraints and ambitions of its era as any masterpiece. For historians, it is essential. For players, it is a curio: a beautiful, interactive jungle gym with a hollow core, forever echoing with the distant, more profound voice of a different, better game.

Final Verdict: 6.5/10 — A historically significant but artistically inconsistent experiment. Technically proficient and occasionally brilliant in its interactivity, but narratively shallow and tonally confused. Its greatest value is as a case study in series evolution and market misalignment.