- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Windows

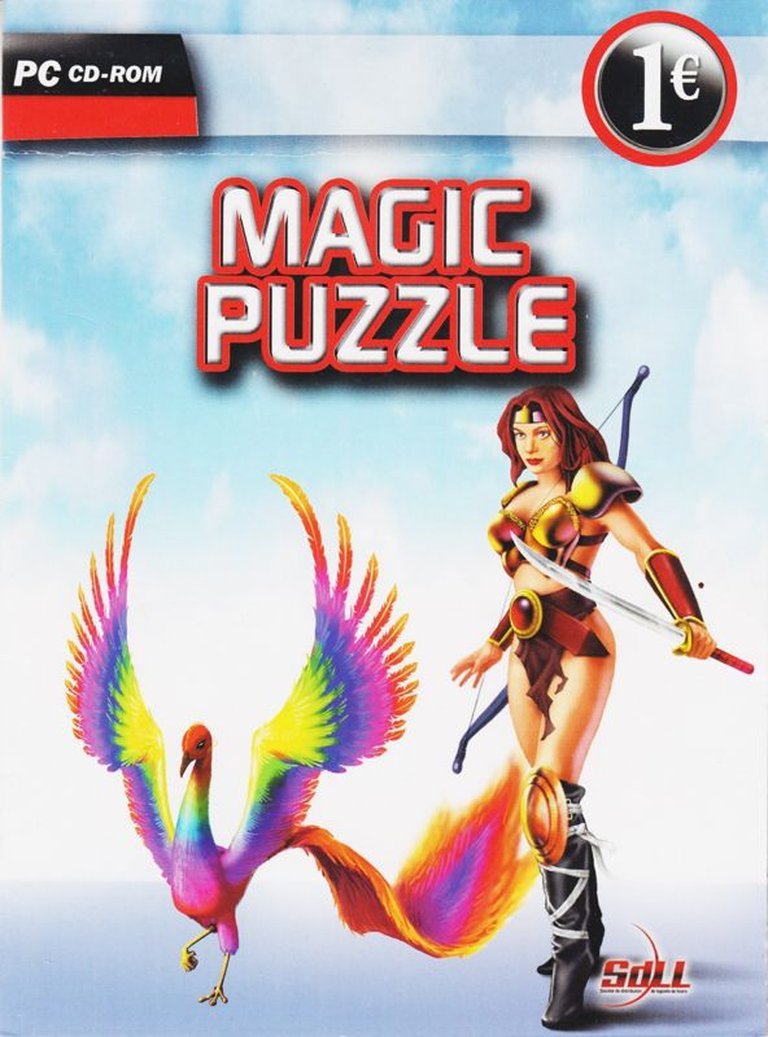

- Publisher: 1C Company, Dikobraz Games, Puzzle Lab, SdLL, S.A.S.

- Developer: Puzzle Lab

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Gameplay: Tile matching

- Setting: Fantasy

Description

Crystal Path is a fantasy-themed puzzle game where players explore isometric, first-person paths adorned with colorful crystals in a magical fairy land. The core gameplay involves tile matching to remove all crystals and advance, with bonuses adding to the enchanting and challenging experience.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Crystal Path

PC

Crystal Path Free Download

Crystal Path (2004): A Forgettable Path in the Puzzle Genre

Introduction: A Whisper in the Casual Gaming Boom

In the crowded landscape of early 2000s casual PC gaming, where titles like Bejeweled, Zuma, and Frozen Bubble reigned supreme, hundreds of niche titles flickered briefly before fading into obscurity. Crystal Path (also known as Magic Puzzle and Тропа магии) is one such title: a 2004 isometric tile-matching puzzle game from the Russian developer Puzzle Lab. It represents a quintessential, yet deeply anonymous, product of the “casual” boom—a game built on a solid, familiar mechanical foundation but endowed with negligible artistic identity, narrative pretense, or lasting cultural impact. This review argues that Crystal Path is not a lost classic but a functional artifact, a competent yet impersonal entry that highlights both the accessibility and the creative stagnation of its genre and era. Its legacy is not one of influence, but of pure, unadulterated ephemerality.

Development History & Context: Puzzle Lab’s Well-Trodden Road

Crystal Path emerged from Puzzle Lab, a studio whose name appears on a constellation of mid-2000s casual puzzle titles including Fresco Wizard, Fiber Twig, and the Charm Tale series. The studio’s portfolio, revealed through MobyGames’ credit linking, shows a specialized focus on a specific subgenre: visually polished, fantasy-themed, tile-matching or inlay puzzles. There is no evidence of a grand creative vision; instead, Puzzle Lab operated as a prolific producer for the casual distribution networks of the time, primarily through publishers like GameHouse, 1C Company (a major Russian/Eastern European publisher), and Dikobraz Games.

The year 2004 was pivotal for digital distribution. While retail boxes on CD-ROM (as noted in MobyGames’ specs) still dominated, platforms like GameHouse’s portal and early Steam were changing how casual games reached players. Crystal Path’s multi-publisher release strategy—spanning Western (GameHouse) and Eastern European (1C, Dikobraz) markets—suggests a pragmatic, revenue-driven development cycle with minimal localization beyond basic text (its Russian title, Тропа магии, confirms a primary development locale). The technological constraints were those of the early DX9 era: modest system requirements (as seen on Steam) targeting mass-market PCs, with isometric 2D or simple 3D graphics designed for low barrier-to-entry. This was not a game pushing boundaries; it was a game filling a catalog slot, built to exploit a proven formula with a new visual skin.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Absence of Story

Crystal Path offers a masterclass in narrative minimalism. The official description—”The dwellers of the fairy land are happy to greet you… Travel through the mysterious paths covered with crystals… if you can remove all the crystals, the ‘creature’ will let you go further”—is not a plot but a gameplay instruction manual dressed in fantasy bardic language. There are no named characters, no dialogue, no escalating conflict. The “creature” is an abstract gatekeeper, the “fairy land” a non-descript backdrop. This complete abdication of narrative is not a stylistic choice but a functional necessity. The game’s sole purpose is to present a sequence of abstract puzzles. The fantasy setting is purely aesthetic—a layer of magical theming (crystals, creatures, paths) applied to the immutable logic of tile matching. There is nothing to analyze thematically because there is no text, no context, and no intentional meaning beyond “clear the board.” It exists in a narrative vacuum, a pure mechanics-first design that was common, even expected, in the casual puzzle space of the mid-2000s.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Competent but Conventional

The core loop, as extracted from the ad blurb and genre classification, is instantly recognizable: match groups of three or more same-colored crystals to eliminate them, with the win condition being the complete clearing of a tile-based path. The innovation, such as it is, lies in the “moving path” mechanic. The description states, “the path you are on is moving forward, and you should be careful not to let crystals touch the bottom of the screen, otherwise the game will be over.” This introduces a classic tetromino-esque pressure element, blending match-3 with a falling-block urgency. The “creature” attempting to block the player introduces a basic adversarial element, likely manifested as obstacles or special tiles that hinder matching.

The mention of “bonuses” suggests power-ups or score multipliers common in the genre (e.g., crystal bombs, color clears), but the source material provides zero detail on their function, acquisition, or impact. The user interface is undescribed but would have been standard for the era: a score display, level indicator, and a clear playfield. There is no evidence of character progression, unlockable content, or metagame. The gameplay is a closed loop of repetition with increasing speed or complexity. From a design standpoint, it is derivative but presumably functional. Its “innovative” aspect—the first-person isometric perspective—is purely a camera angle choice that adds no tactical depth to a puzzle genre almost universally played from a top-down view. It is a cosmetic quirk, not a systemic innovation.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Cosmetics Over Craft

The setting is a generic “fairy land” with “mysterious paths.” Without screenshots or video analysis from the period (the archived executable on the Internet Archive offers no insight), we must infer from the conventions of Puzzle Lab’s other games (Fresco Wizard features Renaissance art restoration; Charm Tale uses fairy tale motifs) and the casual aesthetic of 2004. The art direction was almost certainly bright, saturated, and saccharine, employing a palette of glowing crystals against soft, pastoral or enchanted forest backdrops. The isometric view would have given a slight, pseudo-3D depth to what were likely 2D sprites.

Sound design is referenced vaguely as a “soothing soundtrack” on the GameHouse page. This points to a loop-based, calming musical track intended to reduce player stress—a staple of casual games. Sound effects would have been minimal: pleasant chimes for matches, a dull thud for blocks reaching the bottom (game over), and perhaps whimsical noises for bonus activations. The audio-visual package was designed not to immerse but to reassure, to create a low-intensity, comfortable experience suitable for short, frequent play sessions. It is the auditory and visual equivalent of a beige wallpaper: inoffensive, forgettable, and utterly disposable.

Reception & Legacy: A Silent Fade

There is no critical reception to analyze. Metacritic lists no critic reviews for the PC version. MobyGames shows a “Moby Score: n/a” and only 3-4 collectors. The Steam page, where it was re-released in 2018, shows 10 user reviews, all “Positive,” but these are almost certainly from an era of inexpensive bundled games or nostalgic retro purchases, not reflective of its 2004 launch. Its commercial performance is a mystery, but its presence in the 2007 French compilation Jeux Casuals and continued availability via Steam and My Abandonware suggests it sold just enough to warrant catalog reuse, but never enough to spawn a sequel or significant community.

Its legacy is one of complete absorption into the vast, uncounted mass of casual game history. It left no discernible mark on the match-3 genre, which was evolving toward narrative-driven mobile games like Candy Crush Saga. Puzzle Lab itself seems to have faded, with no modern social media presence or recent releases. Crystal Path is not cited in academic works on game design (unlike the 1,000+ citations for MobyGames itself). It is the very definition of a “forgotten game.” Its only “influence” is as a data point in the story of how dozens of small studios worldwide catered to the early 2000s casual boom with formulaic, low-risk products that prioritized quick development over memorable artistry.

Conclusion: A Path Untrodden by History

Crystal Path is a perfectly functional, ultimately void, puzzle game. It achieves its narrow goal of providing a series of matching puzzles with a slight urgency modifier. It is not broken, nor is it brilliant. It is a ghost of a game, a title whose existence is documented only in database entries, a handful of credits, and the faint digital echo on Steam. In the vast museum of video game history, it belongs not in the galleries of innovation or artistry, but in the overflowing basement storage—a testament to the countless hours of development labor that yield nothing more than a momentary distraction. Its place in history is as a cautionary metric: a reminder that commercial viability and creative significance are not synonymous. For the historian, it is valuable solely as evidence of the era’s market saturation. For the player, it is a 50MB time capsule to a time when “fantasy” meant a different color scheme for the same old match-3 grid. It is, in every sense, a path that leads nowhere worth remembering.

Final Verdict: 4/10 – A mechanically sound but artistically and narratively vacuous relic of the casual puzzle boom, noteworthy only for its profound obscurity.