- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Windows

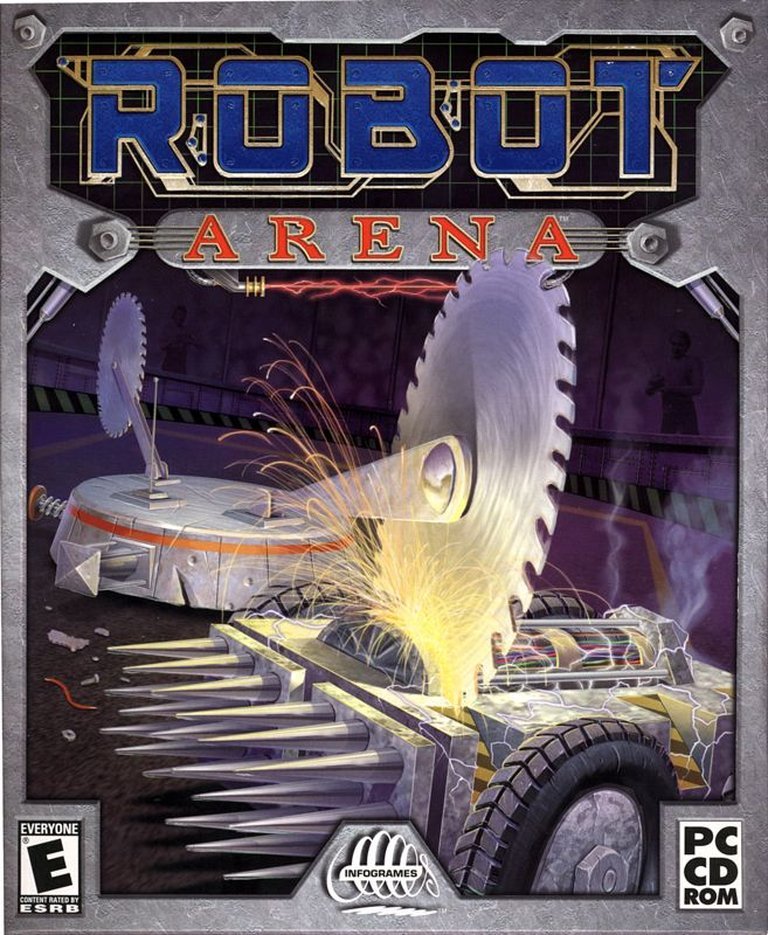

- Publisher: Infogrames, Inc., WizardWorks Group, Inc.

- Developer: Gabriel Interactive, Inc.

- Genre: Action, Driving, Racing

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Arena combat, Design & Customization, Mecha, Upgrade system

- Average Score: 54/100

Description

Robot Arena, released in 2001, is a combat simulation game inspired by TV shows like ‘Battlebots’ and ‘Robot Wars’, allowing players to design and customize their own battle robots with weapons such as axes, hammers, and buzz saws. Players compete in real-time robot battles for cash rewards, which can be used to upgrade machines or repair damage after losses, while supporting both single-player campaigns and multiplayer modes via LAN or Internet.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Robot Arena

Robot Arena Free Download

Robot Arena Guides & Walkthroughs

Robot Arena Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (41/100): Even at the low retail cost of $19.99, Robot Arena isn’t worth it.

Robot Arena Cheats & Codes

PC

Enter codes in the Bot Lab while editing a bot’s name or during the build process.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| cheatbot | Unlocks new items and weapons such as an electric switchblade and a zombie skull. |

| $ | Grants money. |

| Shift + 4 | Grants $50,000. |

Robot Arena: Review

Introduction

In the dawn of the new millennium, as televised robot combat shows like BattleBots and Robot Wars ignited public fascination with mechanized mayhem, developer Gabriel Interactive seized the moment with Robot Arena (2001). This ambitious debut promised to translate the visceral thrill of workshop warfare onto PC screens, allowing players to design, build, and battle their own custom robots. Yet, despite capturing a niche zeitgeist, Robot Arena emerged as a cautionary tale of unfulfilled potential—a title now remembered more for its technical shortcomings than its creative spark. This review dissects Robot Arena‘s historical context, dissecting its gameplay, narrative, art, and legacy to position it not merely as a failed experiment, but as a foundational artifact in the evolution of robot-combat gaming.

Development History & Context

The Newcomers’ Leap of Faith

Gabriel Interactive, a fledgling studio comprising just nine developers including producer Michael Root and lead designer Perry Board, entered the industry with audacious naivety. Operating without prior major releases, they targeted a burgeoning cultural phenomenon: robot combat spectacles dominating cable TV. Their vision was clear: create a sandbox where players could emulate TV champions by welding weapons, armor, and drive systems onto chassis. However, their shoestring budget and inexperience constrained execution. The team lacked established technical frameworks, forcing them to invent physics and design systems from scratch—a monumental task for a debut project.

Technological & Market Pressures

Released in March 2001 by Infogrames and WizardWorks, Robot Arena arrived during a transitional gaming era. PC titles like MechWarrior 4: Vengeance and Operation Flashpoint pushed graphical fidelity, but budget-priced action games proliferated. Gabriel Interactive aimed for a mid-range niche: accessible enough for casual fans but detailed enough for enthusiasts. Yet, without a major publisher’s backing, they faced steep competition from established franchises. Their reliance on basic 3D rendering (pre-Havok physics) and a primitive collision system reflected both technological limitations and rushed development. As Hardcore Gaming 101 notes, the game’s UI quirks—like a permanent “New Player” placeholder—betrayed its amateur roots.

The TV Show Influence

The core design philosophy directly mirrored BattleBots and Robot Wars. Players used a “Bot Lab” to assemble robots from purchasable parts, then competed in tournament-style brackets. However, translating TV spectacle into interactive gameplay proved elusive. The studio’s focus on authenticity—realistic component weights, weapon durability—clashed with the game’s lack of dynamic physics, creating a jarring disconnect between vision and reality.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

A Minimalist Framework

Robot Arena eschews traditional storytelling, framing its “narrative” as a player-driven ascent through robot combat leagues. The plot is a loop of creation, destruction, and rearmament: players start with $1,000, build a robot, fight in tournaments, earn prize money, and repeat. The sparse world-building centers on robotic opponents with evocative names (e.g., “Bear,” “Berserker,” “Emergency”), each embodying archetypes like the “Mighty Glacier” (Raptor) or “Glass Cannon” (Berserker). These AI foes lack backstories, serving as functionally diverse challenges rather than characters.

Themes of Engineering and Survival

The game explores engineering as a brutal sport—where design choices directly determine survival. The punishing economy (selling parts for less than purchase price) reinforces a thematic focus on resource scarcity and strategic compromise. Victory isn’t just about skill; it’s about optimizing within constraints. Dialogue is nonexistent beyond arena announcements, but the UI’s “Tournament Completed” screen and trophy imagery imply a triumphant journey. Yet, this narrative framework is hollow. As TVTropes notes, the “continuing is painful” money system creates a cycle of frustration, not progression. The theme of “creation leading to destruction” feels more like a bug than a feature.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop: Build, Fight, Repeat

The gameplay hinges on three pillars:

1. Robot Construction: In the “Bot Lab,” players select a chassis, then batteries, motors, armor, and weapons (axes, saws, hammers) within budget limits. The grid-free placement system and lack of collision physics make building feel abstract.

2. Combat: Fights are rudimentary. Robots collide like bumper cars, with no lift mechanics, aerial movement, or dynamic damage. Weapons inflict generic damage values, ignoring tactics like wedging or flipping. As IGN noted, the combat “looks great standing still, but give it a complicated task and it all goes to pieces.”

3. Economy: Winning awards cash for repairs/upgrades, but losing forces costly repairs. Selling parts at a loss creates a “continuing is painful” cycle, often requiring players to restart their profile to avoid bankruptcy.

Flawed Systems and Innovations

- Tournament Mode: Linear and unreplayable. Completing it locks the option, forcing players into “Custom Challenges” for grinding.

- Physics: The absence of Havok (used in the sequel) renders combat flat. No part ejection, no environmental hazards—just static brawling.

- Multiplayer: LAN/Internet support existed but was “broken” (GameSpot), with no server search and unstable connections.

- AI Cheating: Opponents boasted double-thickness armor, and some “Middleweight” bots secretly exceeded weight limits (TVTropes).

Despite these flaws, the Bot Lab’s depth—allowing impractical designs like a “Joke Character” with timed-out batteries (TVTropes)—offered emergent creativity. Players could exploit indestructible castors as “Made of Indestructium” armor, demonstrating the system’s hidden potential.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Arenas and Atmosphere

Environments are functional but sterile. Arenas lack the personality of their TV counterparts, featuring flat floors, simple barriers, and absent crowds. The absence of hazards or dynamic elements (e.g., pits, oil slicks) undermines the promised “show” atmosphere. As Absolute Games lamented, the game has “complete absence of atmosphere.”

Visual Direction

3D graphics are dated but serviceable. Robots are blocky but detailed, with visible weapon mounts and armor plates. Textures are bland, and lighting is static. The Havok physics engine’s absence is glaring—robots never flip, weapons never spin with momentum, and debris never flies. Visual feedback during combat is minimal: sparks appear on damage, but fire effects are rare.

Sound Design

Audio is a weak point. Weapon impacts sound flat, and crowd reactions are repetitive. Absolute Games called the sounds “one-dimensional and irritating.” The only standout is a glitched sound file unused in-game: “Watch out, or the giant hammer in this arena will come down on you like a giant… hammer!” (TVTropes), hinting at rushed localization.

Reception & Legacy

Launch-Day Controversy

Robot Arena polarized critics upon release:

– Praise: 7Wolf Magazine awarded 80%, praising its “original project” and network play.

– Scathing Reviews: GameSpot (39%), IGN (43%), and Game Over Online (19%) condemned it. GameSpot infamously stated: “You’d end up getting more entertainment if you randomly chose two movies at an over-priced movie theater.”

– Player Response: Mixed, with MobyGames players averaging 2.7/5. Some enjoyed the “boy-meets-scrap-parts” fantasy (Happy Puppy), while others criticized the “dumb AI” and “crappy damage” (Metacritic user reviews).

Evolution of a Franchise

The game’s legacy is defined by its sequel, Robot Arena 2: Design & Destroy (2003). RA2 fixed core flaws:

– Added Havok physics for aerial flips.

– Scraped the money system for free part selection.

– Enabled custom chassis design with wedges.

– Earned a 77/100 from GameSpy as “a pleasant surprise.”

Robot Arena thus became a historical footnote—the flawed prototype that birthed a cult series. Its influence extends to modern titles like Robot Arena 3 (2016), which, despite Unity 5 upgrades, still faces criticism for clunky building (EncycloReader). The original’s “Game Mod” community (e.g., DSL conversion) also underscores its niche appeal.

Conclusion

Robot Arena stands as a bold, flawed artifact of early-2000s ambition. Gabriel Interactive’s naivete in tackling robot combat—without physics frameworks, budget, or polish—resulted in a product that’s more tech demo than game. Its punishing economy, static combat, and sterile arenas exemplify the risks of chasing a cultural phenomenon without execution finesse. Yet, its legacy endures: it laid the groundwork for RA2’s refinements and proved that robot combat could translate to interactive spaces. For historians, Robot Arena is a vital case study in iterative design—a reminder that even failures can shape genres. Its place in history isn’t as a classic, but as a cautionary blueprint: a title where passion outpaced potential, but whose vision—building, battling, and destroying—echoed into better games. Verdict: A historical curiosity, not a masterpiece, but an essential chapter in robot gaming’s evolution.