- Release Year: 1986

- Platforms: Amstrad CPC, Apple II, Atari 8-bit, Commodore 64, DOS, iPad, iPhone, Windows, ZX Spectrum

- Publisher: Elite Systems Ltd., Mindscape, Inc., Ocean Software Ltd., Throwback Entertainment Inc., U.S. Gold Ltd.

- Developer: Chris Gray Enterprises Inc.

- Genre: Action, Simulation

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: espionage, Helicopter simulation, Puzzle, Stealth, Vehicular combat

- Setting: espionage, Spy

- Average Score: 75/100

Description

Infiltrator is a 1986 action‑simulation hybrid that blends first‑person helicopter piloting with isometric third‑person espionage. Players assume the role of ace pilot‑neurosurgeon Johnny McGibbitts, tasked with infiltrating an enemy camp led by the “Mad Leader”; you must fly behind enemy lines, disguise your helicopter, bluff guards with forged documents, and use sleeping gas or grenades to retrieve vital items before a strict time limit expires.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Infiltrator

Infiltrator Free Download

Infiltrator Cracks & Fixes

Infiltrator Guides & Walkthroughs

Infiltrator Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (75/100): Moby Score 7.5

en.wikipedia.org : Mindscape’s second best‑selling Commodore game as of late 1987.

Infiltrator Cheats & Codes

NES

Enter password at level select or use a Game Genie device.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| BOMB | Level select (start at any mission or enemy base) |

| ZPSLPXZA | Start with more Grenades |

| IASLPXZA | Start with fewer Grenades |

| AASLPXZA | Start with no Grenades |

| LPKUIZTZ | Start with less Spray |

| AAKUIZTZ | Start with no Spray |

| SXKXXIVG | Never lose Grenades outside buildings |

| SZVKAIVG | Never lose Grenades inside buildings |

| SXUXKIVG | Never lose Spray outside buildings |

| SZUKYIVG | Never lose Spray inside buildings |

| SZKLIKVK | Stop timer |

| ILOULXPL | Start with less time |

Infiltrator: Review

Introduction

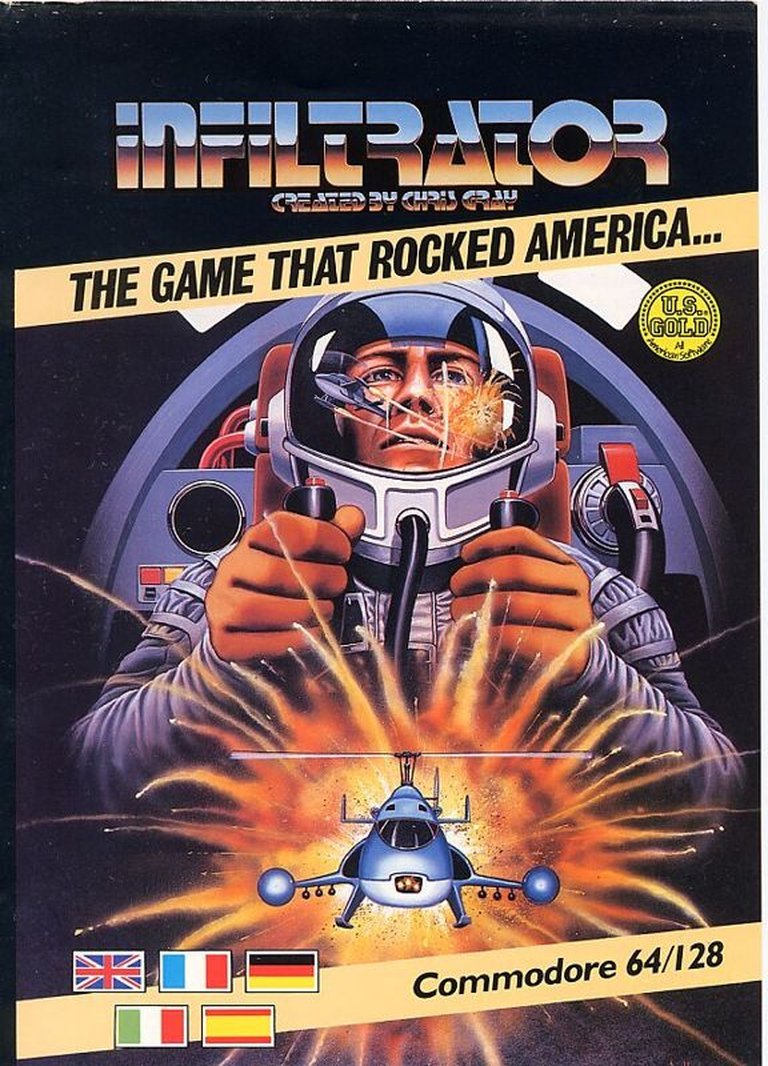

When the Commodore 64’s screen flickered to life in 1986, gamers were suddenly thrust into a hybrid experience that felt like a half‑hour episode of a Cold‑War thriller. Infiltrator—officially billed as Infiltrator: The Game that Rocked America—combined a first‑person helicopter simulator with an isometric, puzzle‑laden infiltration segment. The result was a daring mash‑up that defied genre conventions and, for a fleeting moment, made the 8‑bit world feel cinematic. My thesis is simple: Infiltrator is a historically significant experiment in genre‑blending that, despite its technical quirks, laid the groundwork for later stealth‑action titles and remains a showcase of 1980s design ambition.

Development History & Context

Studio & Vision

The game was the brainchild of Chris Gray Enterprises, a one‑person studio led by veteran programmer Christopher Gray. Gray’s vision was to create an “action film” experience within the constraints of home computers that were, at best, 64 KB of RAM and a 1 MHz 6502 processor. The design aimed to give players a sense of agency both in the air—piloting a heavily armed helicopter—and on the ground—sneaking, bluffing, and disarming enemies.

Technological Constraints

Hardware: The original C64 version relied on multi‑load cassette or floppy disks, often leading to the long loading times noted by contemporary reviewers (e.g., ASM’s comment on “the long loading time”). The graphics were limited to 2‑D scrolling for the flight sections and isometric tile‑based rooms for the infiltration phases. Memory limitations forced the developers to reuse assets across the six missions and to implement an “auto‑mapping” system that was, for its time, a clever way to offset the lack of a persistent world.

Software: The game’s codebase was written in assembly, which allowed for precise control over the helicopter’s physics and the HUD’s real‑time updates (fuel, oil temperature, missile warnings, etc.). However, this low‑level approach also introduced stability issues—players reported a “mean bug” that could crash the ground mission, a problem documented on the C64‑Wiki and by multiple user anecdotes.

Market Landscape

In 1986, the home‑computer market was dominated by arcade‑style action and early RPGs. Flight simulators such as Ace of Aces and Fighter Pilot were popular, while stealth‑action was still nascent (the first Metal Gear appeared the same year). Infiltrator entered this climate as a “spy‑espionage” title, trying to ride the wave of Cold‑War intrigue while also catering to the “Airwolf”‑style helicopter craze. Its dual‑perspective nature—first‑person cockpit, isometric ground—was unusual and allowed it to stand out among pure simulators and pure adventure games.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot Overview

Players assume the role of Johnny “Jimbo Baby” McGibbitts, an absurdly over‑qualified hero (pilot, neurosurgeon, ballistics expert) tasked by the shadowy Whizbang Enterprises to stop the enigmatic Mad Leader. The narrative is delivered through a tongue‑in‑cheek briefing that reads like a parody of spy‑film dossiers: “We need you… The world is on the brink of destruction.” The game’s story is deliberately campy, a design choice that both lightens the tension and underscores the era’s fascination with larger‑than‑life secret agents.

Themes & Motifs

- Dual Identity: McGibbitts’ multiple professions echo the classic “double‑life” spy trope. In‑game, the player must constantly switch between the aerial aggressor (friend or foe) and the covert infiltrator (disguise, forged papers).

- Technology vs. Humanity: The helicopter, dubbed the Gizmo DHX‑3, is a high‑tech weapon platform equipped with missiles, flares, chaff, a turbo booster, and a “Whisper” silent‑mode. Yet the ground missions rely on low‑tech tools—sleeping gas, paper IDs, a mine detector—highlighting a tension between high‑octane firepower and subtle subterfuge.

- Time Pressure: Each ground mission imposes a strict timer (10 minutes in‑game, 20 minutes real‑time), creating a sense of urgency reminiscent of the “countdown” narratives that dominate thriller cinema.

Dialogue & Writing Style

The script leans heavily on humor and exaggerated bravado (“I do not go anywhere without my McGibbits Trim‑Fit™ bullet‑proof super jeans”). While critics like Computer Gaming World later dismissed this as “tongue‑in‑cheek documentation quickly grows tiresome,” contemporary reviewers (Sinclair User, Tilt) praised its “action‑film” vibe. The dialogue functions as both exposition and a meta‑commentary on the era’s over‑the‑top marketing.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop

Each of the six missions is a two‑part loop:

- Helicopter Flight – Take‑off, program the Automatic Direction Finder (ADF), navigate hostile airspace, engage enemy aircraft, and land stealthily.

- Ground Infiltration – Disguise or bluff guards, use inventory items (papers, sleeping gas, grenades, mine detector, explosives), locate security cards, and complete mission‑specific objectives (photograph documents, rescue Dr. Gump, neutralize nerve gas, plant bombs).

Flight Controls & HUD

- Joystick controls pitch, roll, and throttle; keyboard keys activate systems (B‑battery, S‑computer, I‑ignition, G‑cannon, R‑missiles, F‑flares, C‑chaff, W‑whisper, +/‑‑turbo).

- The HUD displays artificial horizon, compass, speed, fuel, oil/battery temperature, altitude, RPM, and missile warnings.

- Whisper Mode is essential for silent landings; failing to engage it will trigger an alarm and abort the mission.

Ground Mechanics

- Inventory System: A simple radial menu (selected via space bar) lets players activate one of five items at a time.

- Disguise & Papers: When confronted by a guard, the player must switch to “papers” and present them; success is determined by a hidden script that checks the guard’s AI state.

- Combat: While the ground is primarily stealth‑oriented, players can resort to sleeping gas or gas grenades to incapacitate guards.

- Timer & Pressure: The ground phase runs on a visible countdown; failure to exit before it reaches zero results in mission abort and a forced reload.

Puzzle Elements

- Security Cards are hidden in multi‑room buildings; the player must explore, map rooms (the auto‑mapping feature updates a mini‑map), and locate the card to unlock doors.

- Chemical Analysis (Mission 2) requires gathering four containers, delivering them to a lab, and interpreting the results to locate the nerve‑gas neutralizer.

- Explosive Placement (Mission 6) is a classic “plant‑the‑bomb” puzzle with a short escape window.

UI & Accessibility

The interface is dense, with multiple toggles (HUD, communications, status displays) that require frequent key presses. Modern reviewers note this as “overwhelming,” but for 1986 audiences it was a testament to the developers’ ambition to provide a cockpit‑like experience on a home computer.

Innovative & Flawed Systems

- Innovation: The blend of real‑time flight simulation and isometric stealth was virtually unheard of on 8‑bit hardware. The ADF navigation system, complete with a programmable frequency, added a layer of realism rare for the era.

- Flaws: Long loading times, occasional crashes, and a UI that demands rapid key presses can break immersion. The ground graphics are notably weaker than the flight vistas—a point highlighted by Computer Gamer (“enter a building and they become disappointing”).

World‑Building, Art & Sound

Setting & Atmosphere

The game’s world is a loosely defined “enemy country” populated by a series of fortified compounds. The aerial environment is a scrolling landscape of mountains, forests, and distant enemy bases. On the ground, each compound is a maze of rooms rendered in isometric tiles, with color‑coded rooms (red for important, green for entrances, blue for neutral) that aid navigation.

Visual Direction

- Flight: The C64 version uses multi‑palette sprites for the helicopter and enemy jets, achieving a “graphically excellent” look praised by Zzap! and ASM. The artificial horizon and other cockpit instruments are rendered with crisp vector graphics despite the hardware’s limited resolution.

- Ground: Buildings are built from tiled walls and floors, with simple but functional UI overlays (mini‑map, inventory). The isometric view provides depth, though the sprite detail is reduced compared to the cockpit.

- Color Palette: The use of bright reds and greens for room importance is a practical design choice, ensuring the player can quickly identify key areas on a low‑resolution screen.

Sound Design

- Music & Effects: The score consists of short, looping chiptune motifs that shift between tense aerial combat and stealthy infiltration. Sound effects for missiles, flares, and the “whisper” mode are distinct, providing auditory cues for danger (e.g., missile warning lights accompanied by a siren).

- Voice‑like Text: While no voice acting exists, the game’s on‑screen text (e.g., guard dialogues, system messages) is delivered in a stylized, humorous tone that reinforces the parody narrative.

Contribution to Experience

The juxtaposition of a high‑octane flight simulation with a slower, methodical stealth segment creates a rhythm that keeps players engaged. The visual contrast between the expansive sky and cramped interior rooms heightens the sense of being a “super‑soldier” who can dominate both air and ground.

Reception & Legacy

Critical Reception (Contemporary)

- Positive: Sinclair User and Tilt gave perfect scores (5/5, 6/6), applauding the “action‑film” feel and the “very varied” gameplay. ASM awarded 9.75/10, calling it “a brilliant game of excellent graphics and great variety.”

- Mixed: Zzap! (92%) and Your Sinclair (80%) appreciated the novelty but noted the steep learning curve and occasional boredom after the initial excitement.

- Negative: Computer Gaming World (1994) gave it a single star, criticizing the documentation’s “tongue‑in‑cheek” style and labeling the program as “dated.” Commodore User’s 50% review cited a lack of cohesion despite solid graphics.

Commercial Performance

By late 1987, Infiltrator was Mindscape’s second‑best‑selling Commodore title, indicating solid market penetration. The game’s presence on multiple platforms (C64, ZX Spectrum, Amstrad CPC, DOS, Apple II, Atari 8‑bit) and later re‑releases on iOS, Android, and Windows attest to its enduring commercial viability.

Influence & Sequels

- Sequel: Infiltrator II: The Next Day (1987) expanded on the original’s mechanics but received a scathing zero‑star rating from Computer Gaming World, suggesting that the sequel failed to capture the original’s charm.

- Series Continuation: A third installment was hinted at in Compute!’s Gazette (1990), though never materialized.

- Cultural Footprint: The game was novelized in the Worlds of Power book series, indicating its popularity among younger audiences. Its design philosophy—mixing simulation with stealth—can be seen in later titles such as Metal Gear Solid (1998) and the Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon series, which also require players to toggle between overt combat and covert infiltration.

Modern Re‑evaluation

Retro‑gaming communities (e.g., Lemon64, C64‑Wiki) continue to celebrate Infiltrator for its ambition, often rating it around 7.5–8/10. The game’s quirks (long loading, occasional crashes) are now viewed through a nostalgic lens, while its core gameplay loops remain engaging for modern players who appreciate “old‑school” design.

Conclusion

Infiltrator stands as a bold experiment that dared to blend two disparate genres on hardware that was scarcely capable of either on its own. While its technical execution is imperfect—long loads, occasional crashes, and a UI that demands rapid memorization—the game’s conceptual audacity deserves recognition. It captured the zeitgeist of 1980s action cinema, introduced a hybrid gameplay loop that foreshadowed later stealth‑action hybrids, and left a mark strong enough to inspire sequels, novelizations, and ongoing retro admiration.

Verdict: Infiltrator is not a flawless classic, but it is a seminal piece of video‑game history that showcases the creative limits of early home‑computer development. For historians and gamers alike, it offers a fascinating case study in how ambition can outweigh hardware, and how a single‑person studio could, for a brief shining moment, make the world feel a little more like an action film.

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4 out of 5) – a testament to its pioneering spirit, tempered by its era‑bound rough edges.