- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Dartmoor Softworks GmbH & Co. KG, eSofnet

- Developer: g2G Entertainment Company Ltd.

- Genre: Action, RPG

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Co-op, LAN, Online Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Loot, Magic, Party-based, Quests, Real-time combat

- Setting: Fantasy

Description

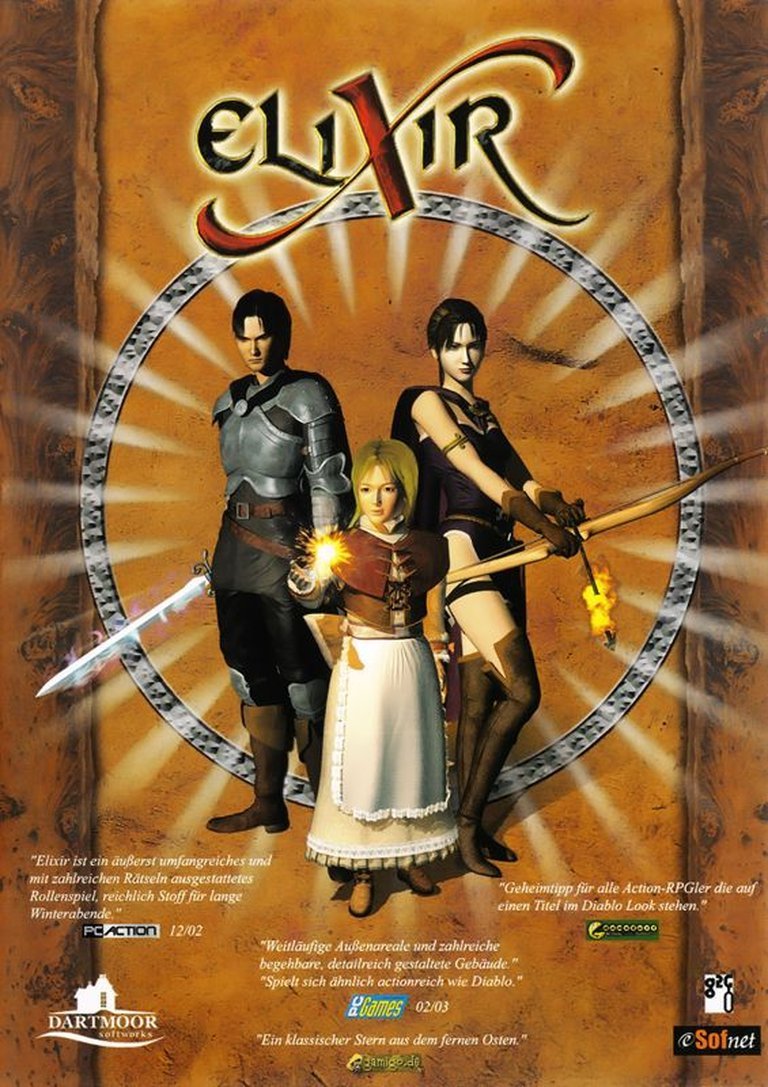

Elixir is a fantasy action RPG set in a world where an ancient prophecy foretells the rebirth of the Ingoles tribe’s god as a magical infant, Elixir, who survives a massacre by the evil king Ektele Ulka and embarks on a journey with allies to seek revenge. Featuring Diablo-inspired real-time combat with party-based mechanics (up to four characters controlled simultaneously without pause), isometric visuals, and a structure of 52 missions and 80 quests focused on loot collection and character advancement.

Where to Buy Elixir

PC

Elixir Reviews & Reception

everygamegoing.com : This is as irritating at it is disorientating.

Elixir (2002): A Scholarly Dissection of a Forgotten Action-RPG Curio

Introduction: The Prophecy of Obscurity

In the vast, ever-expanding library of video game history, certain titles exist not as celebrated classics or infamous failures, but as quiet, perplexing footnotes—games that arrived with a whisper of ambition only to be drowned out by the cacophonous roar of their contemporaries. Elixir (2002), developed by the obscure g2G Entertainment Company Ltd. and published by the equally niche eSofnet and Dartmoor Softworks, is precisely such a title. It is a game that wears its inspirations on its sleeve—primarily Blizzard North’s Diablo—yet attempts a crucial, arguably fatal, deviation: a fully party-based, real-time action-RPG with no pause functionality. This review will argue that Elixir is a fascinating case study in constrained development, genre hybridity gone awry, and the perils of arriving years too late to a genre-defining party. Its legacy is not one of influence, but of a clear, cautionary blueprint: to innovate within a established formula, one must first master the fundamentals that made the formula successful. Elixir stumbles at the first hurdle, forever consigning it to the bargain bin of gaming history.

Development History & Context: Shadows of Giants

The development history of Elixir is as obscure as the game itself. The primary credited developer is g2G Entertainment Company Ltd., a studio with no other known releases on MobyGames, suggesting it was a small, possibly transient team. The publishers, eSofnet and Dartmoor Softworks GmbH & Co. KG, were minor players in the early 2000s Western PC market, often associated with budget and imports. There is no evidence of a major marketing push or a known development timeline; the game simply appeared on September 5, 2002.

This context is critical. Elixir launched into a landscape utterly dominated by two titans: Blizzard’s Diablo II (2000) and Snowblind Studios’ Baldur’s Gate: Dark Alliance (2001). Diablo II had perfected the solo-centric, click-to-attack action-RPG loop with unparalleled loot mechanics, atmosphere, and polish. Dark Alliance had successfully adapted the party-based, real-time-with-pause gameplay of Baldur’s Gate to a console-friendly,动作-oriented format. Elixir tried to merge these two philosophies—the frantic solo clicking of Diablo with the multi-character management of Dark Alliance—but without the essential pause mechanic that made the latter playable. Furthermore, its presentation was technologically inferior to both. In an era pushing towards 1024×768 resolutions and advanced 3D acceleration, Elixir was locked at a 640×480 pixel resolution with “altbacken” (old-fashioned) 2D graphics that lacked transparency effects, making enemies and items blend into the background. It was, as one critic noted, a game that looked “deutlich schlechter [aus] als das sechs Jahre alte Diablo” (clearly worse than the six-year-old Diablo). The technological constraints were not a creative limitation but a definitive flaw.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Convoluted Revenant Saga

The narrative premise of Elixir is delivered with the grim earnestness of a dark fantasy novel but the clarity of a translated muddle. The prophecy of the Ingoles, a tribe genocided by humans, sets a high-stakes, mythic stage. Their god’s reincarnation as a vengeful infant, Elixir, immediately creates a protagonist defined by traumatic origin rather than agency. The antagonist, King Ektele Ulka, initiates a kingdom-wide infanticide, a trope of shocking brutality that establishes a world of profound moral darkness.

Thematically, the game grapples with genocide, revenge, and the burden of destiny. Elixir’s journey from a hunted baby to a magical warrior is one of forced maturation. The party-based structure reinforces a “found family” theme, as she is continually accompanied by allies who help her survive. However, these potent themes are consistently undermined by execution. Critics universally cited the “langatmigen Dialoge” (long-winded dialogues) and “verworrene” (convoluted) story. The sheer density of proper nouns—Ingoles, Ektele Ulka—and the delivery through static text screens or rudimentary in-engine cutscenes (“maue Übersetzung” – poor translation) strips the narrative of emotional weight. What could be a poignant tale of a child of war becomes an exhausting, “zungenbrechenden Fantasienamen” (tongue-breaking fantasy names) chore to parse. The story’s potential is its greatest asset and its most glaring failure; it compels curiosity but exhausts the player with its delivery.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Hectic Heart

Elixir’s core identity is forged in its real-time, click-to-attack combat system, directly inherited from Diablo. Players left-click to move and attack, with right-click for special abilities or magic. The progression loop—kill monsters, gain experience, find better gear—is intact. The critical, defining innovation (and fatal flaw) is the four-character party controlled simultaneously with no pause function.

This design choice creates a state of perpetual, “hectic” (hectic/chaotic) management. Unlike Baldur’s Gate, where pausing allows for tactical party commands, Elixir demands frantic, real-time micromanagement. The player must constantly click to position and attack with all party members, resulting in a blur of activity. Critics noted that while this made combat “angenehm flott” (pleasantly fast), it also risked descending into “stumpfes Gemetzel” (mindless slaughter) and was a primary source of frustration. The lack of paging negates strategic depth; positioning is reactive, not planned.

The structure consists of 52 missions and 80 quests, providing a massive quantity of content. However, the “motivierende Prinzip” (motivating principle) of loot and leveling is hampered by the game’s technical presentation. The isometric view, while clean, suffers from poor enemy and item visibility due to the lack of transparency, making the core activity—finding loot—needlessly difficult. Character progression exists but feels shallow without meaningful tactical choices to employ it. The systems are a paradox: a complex party management system grafted onto a simplistic, stream-lined action core, with the management complexity winning out to create anxiety rather than satisfaction.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Aesthetic Anachronism

Visually, Elixir is a time capsule of early 2000s budget development. Its isometric, 2D sprite-based aesthetic is immediately and irredeemably dated upon release. The 640×480 resolution in 2003 was “völlig indiskutabel” (completely unacceptable). Environments are simplistic, with little environmental storytelling or atmospheric detail. The character animations are described as “eintönig” (monotonous), and the complete absence of dynamic lighting or shadows leaves the world visually flat.

This technical poverty directly impacts world-building and atmosphere. A fantasy realm rife with prophecy and genocide should feel oppressive, ancient, or magical. Elixir’s world feels like a generic, empty cardboard backdrop. The lack of voice acting (“keine Sprachausgabe”) forces all narrative and character interaction into text, severing any potential emotional connection. Sound design is minimally described in sources, implying it was as unremarkable as the visuals—a functional backdrop rather than an immersive layer. Together, these elements form the game’s most consistent criticism: an “unansehnliches Äußeres” (unsightly appearance) that actively discourages engagement. The atmosphere intended by the narrative is completely nullified by the presentation.

Reception & Legacy: The Calculus of Mediocrity

Elixir received a critical mauling, averaging a mere 56% based on nine German reviews. The consensus was brutally consistent:

* Graphics & Tech: Universally condemned as obsolete and poorly implemented.

* Pacing & Control: The frantic, unpaused party control was a major point of contention, seen as more frustrating than innovative.

* Narrative: The story was acknowledged as potentially interesting but buried under poor translation and long, unskippable text.

* Value & Comparison: It was almost universally unfavorably compared to Diablo II and the recently released Sacred (2004). One critic’s verdict sums it up: “Wer soll sich ‘Elixir’ kaufen wo es doch Diablo und Konsorten gibt?” (Who should buy Elixir when Diablo and its ilk exist?).

Commercially, it was a non-entity. Its MobyScore of 6.1 and ranking of #23,581 of ~27K games, with only 9 collectors documented, speak to its obscurity. It had no discernible influence on the industry. It did not pioneer the party-based ARPG; Dark Alliance had already done it better on consoles, and PC titles like Van Buren (the canceled Fallout 3) and later Torchlight series would explore party mechanics with more finesse. Elixir’s legacy is purely as a cautionary tale: a game that identified a potential niche (party-based Diablo) but executed it with such technical incompetence and presentational poverty that it guaranteed irrelevance. It is a forgotten stepchild in a genre dominated by giants.

Conclusion: The Definitive Verdict

Elixir (2002) is not a “bad” game in the sense of being broken or unplayable. It is a profoundly mediocre one, built on a fundamentally flawed core mechanic (unpaused party control in a click-based ARPG) and presented with an aesthetic befitting a late-1990s shareware title. Its narrative skeleton shows signs of a compelling, dark fantasy tale, but the flesh is rotten with poor localization and static delivery. In the ruthless marketplace of 2002/2003, it was a game with no raison d’être.

To analyze it is to analyze a ghost—a faint echo of Diablo’s brilliance and Baldur’s Gate’s tactical depth, but an echo distorted by poor production values and questionable design priorities. It holds no nostalgic value for mainstream audiences and no academic interest beyond demonstrating the commercial perils of misjudged genre hybridization. Its place in video game history is not on a pedestal, but in a museum cabinet labeled “Curiosities of the Early 2000s: Ambitious Ideas, Limited Execution.” Elixir is, ultimately, the game that proves sometimes the most potent magic is the one that makes you disappear from the collective memory.

Final Score: 4/10 – A Forgotten Formula, Poorly Executed

For historians: A clear example of a ‘me-too’ game that missed every mark except quantity of content.

For players: Not worth seeking out; its systems are frustrating and its presentation actively harmful to engagement.