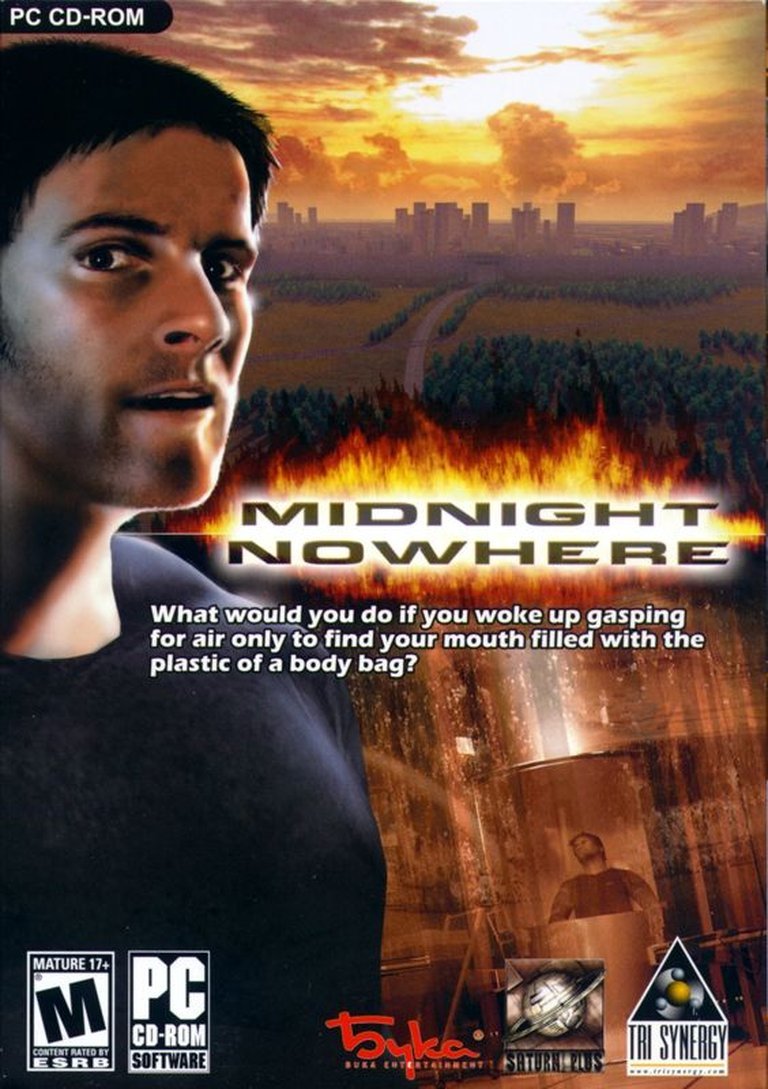

- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Buka Entertainment, Meridian4, Inc., Microforum International, Oxygen Interactive Software Ltd., Tri Synergy, Inc.

- Developer: Saturn Plus

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Point-and-click, Puzzle

- Setting: City, Hospital, Russia

- Average Score: 60/100

- Adult Content: Yes

Description

Midnight Nowhere is a horror adventure game where an amnesiac man awakens in a morgue in the panic-stricken city of Black Lake, Russia, amidst a wave of horrific slaughters. Players engage in point-and-click gameplay to explore environments, solve puzzles, read documents, and interact with characters to uncover the truth behind the brutal crimes, all within a dark, cinematic narrative with adult themes and strong language.

Gameplay Videos

Midnight Nowhere Free Download

Midnight Nowhere Cracks & Fixes

Midnight Nowhere Patches & Updates

Midnight Nowhere Guides & Walkthroughs

Midnight Nowhere Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (88/100): The best title of the year to come for the exciting and morbid horror genre. Midnight Nowhere is a fine and classic example of what gaming should be – stimulating, playable, refreshing and real.

metacritic.com (70/100): While possessing a solid visual and audio presentation, its gameplay suffers from bizarre puzzle design that is far from intuitive. Although a streamlined interface help to make interacting with game environments easy, the unusual puzzles make it difficult to progress through this intriguing game.

metacritic.com (63/100): The pity is that you get the feeling the game would be a lot more effective if the main character had a drier, more morbid sense of humor. As it is, the attempts to crack weird jokes takes away from the otherwise eerie atmosphere of the game.

metacritic.com (60/100): Midnight Nowhere will leave you feeling like you’re in the middle of nowhere. Horror game fans will probably be able to tolerate the game, but others might have a problem.

metacritic.com (41/100): It’s dull, mistranslated, claustrophobic (in a bad way) and thoroughly aimless. No amount of naked women adorning the walls can disguise the fact that Midnight Nowhere simply isn’t much fun.

metacritic.com (21/100): Midnight Nowhere is offensive, crude, disgusting, sick, foul, and stock full of jokes about necrophilia.

metacritic.com (3/100): Unfortunately, the best part of this game was uninstalling it and using the disks for coasters while taking a big gulp of Pepto Bismol.

mobygames.com : A bit sick .. Unconventional story, clunky interface

monstercritic.com (78/100): It’s an excellent point-and-click adventure game and a good addition to any genre fan’s library, provided you are over the age of 18 and don’t mind a little full frontal nudity.

Midnight Nowhere: A Deep Dive into a Cult Horror’s Flawed Brilliance

Introduction

In the annals of early 2000s adventure gaming, few titles are as confounding and compelling as Midnight Nowhere. Released in 2002 by the Russian studio Saturn Plus and published internationally by entities like Buka Entertainment and Oxygen Interactive, this point-and-click horror adventure carved out a niche so specific it remains largely invisible in mainstream gaming discourse. Its legacy is one of stark contradictions: praised for its oppressive atmosphere and audacious narrative yet crucified for its clunky interface, juvenile tone, and problematic presentation. This review argues that Midnight Nowhere is not merely a failed horror game but a fascinating, deeply flawed artifact of its time—a product of post-Soviet development ambition grappling with technical limitations, cultural translation, and a fundamentally dissonant design philosophy. To understand it is to peer into a unique moment where Eastern European game development tried to shock Western audiences, achieving notoriety more through infamy than acclaim, yet leaving an indelible mark on those who braved its morgue-filled corridors.

Development History & Context

Midnight Nowhere emerged from the fertile, chaotic ground of early 2000s Russian game development. Its primary developer, Saturn Plus (also credited as part of the “Dvenadtsat’ Stuljev” or “Twelve Chairs” collective), was a group of around 75 individuals, a significant team for the era and region. The project was helmed by Alexey Nikanorov (Director) and Nikolay Khudentsov (Project Manager/Leading Programmer), with key contributions from artists like Nikolai Mesheryakov (Chief Artist) and programmers like Dmitriy Lobov (Scripts Programming/Game Assembly/Sound Effects). The game was built on a modified version of the engine used for Jazz and Faust (a 2000 Russian adventure game), a technical foundation that already showed its age.

The technological constraints were palpable. The game employs a mixed 2D and 3D graphical approach: pre-rendered 2D backgrounds create detailed, cinematic scenes, while 3D models animate characters and key objects. This hybrid method was common in the late 90s/early 2000s for adventure games seeking richer visuals but limited by 3D rendering power. The result is a visually striking but often dark and muddy aesthetic, where the contrast between static, painted environments and polygon-based models can be jarring. The use of Bink Video middleware (noted on MobyGames) for cutscenes was standard, but compression and resolution choices contribute to the game’s gritty, low-budget feel.

The gaming landscape of 2002 was dominated by the rise of 3D action and the tail end of the classic point-and-click adventure. Western studios like LucasArts and Sierra had largely moved on, while European and Russian developers were stepping in to fill the gap, often with niche, adult-oriented titles. Midnight Nowhere was explicitly designed for the “R-rated” film audience, with a Mature (M) ESRB rating (or equivalent) due to its graphic violence, strong language, drug references, and pervasive sexual imagery. This was a bold, if risky, marketing angle—positioning the game as an adult horror experience akin to a gritty crime thriller or splatter film, not a family-friendly puzzle adventure.

The game’s title itself tells a story of cultural translation. Known in Russia as “Chornyj Oasis” (Чёрный Оазис), its working title “Black Oasis” never fully left the build (evidenced by the “OASIS” string in the readme and CD label). The international title “Midnight Nowhere” is almost unknown in its country of origin, a symbol of its disjointed identity. This bifurcation hints at the core tension within the game: a Russian sensibility about violence, decay, and dark humor being filtered through a Western-focused localization that often lost the plot—literally and figuratively.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The plot is deceptively simple: an amnesiac man awakens naked in a body bag inside a chaotic morgue in the fictional, panic-stricken Russian city of Black Lake, which is being terrorized by a serial killer (or something worse). The player must escape the morgue, navigate a city under military quarantine, and piece together their identity and the killer’s motives. The narrative unfolds through exploration, document reading, and interactions with a cast of decrepit, dangerous characters.

Themes are viscerally grounded in body horror, existential dread, and moral decay. The setting is a near-future dystopia (note inconsistent dates: 2015 vs. 2019 in documents) where society has collapsed into primal violence. The game relentlessly presents corpses, blood, and visceral carnage as environmental storytelling—a choice that aligns with its “surreal horror” aspiration but often crosses into gratuitousness.

Characterization and dialogue are the game’s most contentious elements. The protagonist is defined by a wry, sarcastic, and frequently lewd internal monologue. While some reviewers (like Jeanne on MobyGames) found this “off the wall” humor occasionally funny, most found it juvenile, repetitive, and tonally dissonant. His constant, objectifying commentary on the numerous naked female corpses and explicit pin-ups (“with a little more silicone,” “princess,” etc.) is not a nuanced character trait but a relentless, grating motif. As the GameBoomers review astutely observed, “after the 15th reference to a cold shower… I just got pretty tired of the lack of creativity in the dialogue. 20 times might have been slightly humorous – maybe – but 100 times and you just want to shoot someone.” This dialogue fundamentally clashes with the game’s attempted serious horror, undermining tension and making the protagonist unsympathetic.

The plot structure is a classic adventure game “puzzle chain”: find key A for door B, use item C on corpse D, etc. However, the narrative coherence suffers. Reviews consistently note a confusing, rushed, and philosophically opaque ending that fails to synthesize the game’s esoteric lore. Scattered documents hint at a deeper, possibly supernatural conspiracy involving a cult or entity called “the Hollow,” but the payoff is murky. The story’s “unconventional” nature (as Jeanne puts it) often feels less like intentional ambiguity and more like poor translation and scripting. Inconsistencies (like the timeline jumps) and the sheer volume of irrelevant, explicit “adult” content (wall posters, playing cards, computer screensavers) make the narrative feel haphazardly assembled from a checklist of “edgy” concepts rather than a cohesive whole. The thematic aspiration seems to be a David Cronenberg-esque body horror or a Silent Hill-style psychological terror, but the execution leans closer to a sordid, adolescent exploitation piece.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Midnight Nowhere is a third-person, point-and-click adventure with a cinematic camera that often frames scenes dramatically. The core loop is exploration, inventory management, puzzle-solving, and dialogue. However, its interface is its most infamous and damning flaw.

The game uses a verb coin-style interface reminiscent of early LucasArts titles, but implemented with crippling inconsistency. Players must manually select one of four icons (Look, Use, Grab, Talk) from a menu bar before interacting with a hotspot. The problem is multi-fold:

1. No Visual Feedback: Hotspots only highlight when the correct verb is selected. If you need to “Use” an object but have “Look” active, nothing happens. There is no universal “active” cursor.

2. Character Obscuration: Clicking to move the character often places him directly in front of the object of interest, blocking the view and requiring cumbersome repositioning. This is exacerbated by the game’s fixed camera angles.

3. Pixel Hunting/Tiny Hotspots: Many critical interactive elements are minuscule, visually indistinguishable from background detail, and placed in extensively decorated scenes. As multiple reviews lament, this turns progression into a “painstaking egg hunt” (GameBoomers). Hotspots can be so close together that clicking one inadvertently triggers another, or fails entirely.

4. Inconsistent Logic: What works with which verb is often non-intuitive. As the GameBoomers review details, getting batteries from a radio required a “weird combo” of verbs not indicated by any clue, forcing players to walkthroughs.

Puzzle design is a mixed bag. Structurally, it’s heavily reliant on “find the key for the locked door” mechanics, leading to a repetitive, sometimes monotonous experience. There are no action sequences, no sudden death, and no timed puzzles—a relief for pure adventure fans. However, the puzzles often suffer from obscurity due to the interface, not inherent complexity. Many are “easy… if you have successfully picked up the right item” (Jeanne), but finding that item is the chore. The infamous puzzle involving cutting a finger off a corpse with an axe to bypass a fingerprint scanner (cited by GameStar) exemplifies the game’s commitment to gratuitous horror over elegant puzzle design.

Character progression is nonexistent; the protagonist gains no skills or abilities. The UI lacks modern conveniences: saved game names are limited in characters, but unlimited slots are a plus. Subtitles can be toggled, a crucial feature given the audio issues (see below). The absence of a “highlight all hotspots” function is a glaring omission in a game so dependent on visual inspection.

In essence, the gameplay systems actively work against the player, transforming what could be a moody, investigation-driven adventure into a frustrating exercise in interface archaeology. It’s a game where the primary challenge is not solving the mystery, but deciphering the game’s own opaque rules of interaction.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The world of Black Lake is the game’s most consistently praised aspect. It presents a bleak, industrial dystopia—a decaying hospital, a grimy police station, a dilapidated prison—rendered with a surreal, nightmarish aesthetic. The 2D pre-rendered backgrounds are highly detailed, littered with environmental storytelling: scattered bodies, hastily abandoned rooms, violent posters, and pervasive symbols of decay. The art direction deliberately uses muted, cold color palettes and heavy shadows to cultivate an atmosphere of despair and claustrophobia. The 3D character models are adequately animated for the era, though their stiff movements and occasionally awkward lip-syncing (lips continuing to move after dialogue ends, noted by Jeanne) break immersion.

The setting is populated by a disturbing gallery of explicit, provocative imagery. Nudity is omnipresent and non-diegetic—it’s not just in a brothel or private room, but on posters in a hospital, on playing cards in a police station, on computer screensavers. This isn’t integrated world-building; it feels like shock-value padding, as if the developers believed an “Adult” rating required visual titillation regardless of narrative justification. As Jeanne sharply critiqued, “It’s as if they added all of that art just to shock. (Or did they do it to ensure an ‘Adult’ rating?)” This choice cheapens the atmosphere, making the world feel less like a coherent horror setting and more like a juvenile, misogynistic fantasy projection.

The sound design is a relative high point. The musical score is varied, atmospheric, and effectively enhances the dread—main themes are haunting and memorable. However, the audio mix is notoriously problematic. Sound effects and music often drown out crucial dialogue, forcing constant manual volume adjustments (Jeanne’s repeated complaint). The English voice acting is generally competent, delivering the problematic lines with enough gravitas to be passable, but the localization itself is infamously poor. Reviews from GameSpot, GameSpy, and Withingames single out the translation as a major flaw, turning already awkward dialogue into nonsensical, cringe-inducing sentences. This linguistic failure severs any potential connection to the narrative, making plot comprehension a battle against incomprehensible text and speech.

Together, the art and sound create an uneasy, oppressive experience that is technically impressive in its environmental density but consistently undermined by its tonal incoherence and technical audio/translation issues. The world feels sick and real, but the reasons for its sickness are muddled by adolescent posturing.

Reception & Legacy

Midnight Nowhere received a scathing to lukewarm critical reception, averaging a 56% on MobyGames from 28 critic reviews. The range is telling: Armchair Empire championed it (88%), calling it “the best title of the year” for horror, while Computer Gaming World savaged it (20%), advising readers to avoid it if they weren’t fans of “lewd, foul-mouthed” content. Most landed in the mediocre 50-70% range, with common criticisms aligning perfectly with the interface, translation, and juvenile tone. Adventure Gamers (60%) summarized it well: “The puzzle structure, iffy dialogue, and subject matter make this a hard recommendation to a general audience.”

Commercially, it was a niche title. It had limited physical distribution in the West (via publishers like Tri Synergy and Oxygen Interactive) and is now a rare, expensive collector’s item on the secondary market. Its Mature rating and explicit content made it a tough sell for mainstream retailers, a factor noted by multiple reviewers predicting it would be a UK/import-only title.

Its legacy is that of a cult curio, not an influential classic. It did not spawn sequels or a notable fan community beyond dedicated walkthrough authors and abandonware preservationists. Its influence on subsequent games is negligible; it does not appear in design retrospectives or “greatest horror game” lists. Instead, it serves as a cautionary tale in several arenas:

1. Localization: A textbook example of how poor translation can destroy narrative immersion and tone.

2. Interface Design: A warning against clunky, non-intuitive verb systems in an era moving toward context-sensitive cursors.

3. Cultural Translation: Demonstrates the pitfalls of exporting a region-specific sensibility (Russian dark humor, graphic violence) without refinement for global audiences.

4. Narrative Cohesion: Shows how excessive, non-integrated “adult” content can trivialize serious themes.

On platforms like Abandonware, it’s preserved but plagued by compatibility nightmares. Modern Windows versions require patches like dgVoodoo2 and specific compatibility settings (Windows 98/ME mode), with issues like music freezing or red-screen crashes (as detailed in user comments on My Abandonware). This technical fragility further cements its status as a preserved artifact, not a playable classic.

Conclusion

Midnight Nowhere is a game of profound missed opportunities. Its world is gorgeously macabre, its core mystery has hooks, and its ambition to be a mature horror adventure is commendable. Yet, it is strangled by its own execution. The interface is a relic of bad design, the translation a barrier to understanding, the humor a constant irritant, and the pervasive nudity a cheapening gimmick that betrays its thematic aspirations.

In the pantheon of adventure games, it holds no place of honor. It is not a forgotten gem like Grim Fandango or a classic like Myst. Instead, it is a fascinating, frustrating fossil—a snapshot of a specific moment when Russian development houses were experimenting with genre and content for Western markets, often with clumsy results. Its value today is purely historical and anthropological: to study it is to understand the growing pains of a globalizing industry, the perils of cultural miscommunication, and the fine line between bold horror and juvenile exploitation.

Final Verdict: Midnight Nowhere is a 5/10 experience. For the hardcore horror adventure historian with infinite patience, a walkthrough, and a high tolerance for discomfort, it offers a unique, atmospheric, and sometimes genuinely creepy journey through a brilliantly realized hellscape. For everyone else, it is a cautionary tale best observed from a distance. It is not a game to be “rediscovered” as a classic, but one to be remembered as a flawlessly flawed curiosity—a midnight oil burning low, illuminating more about its own creation than the dark corners it tries to explore.