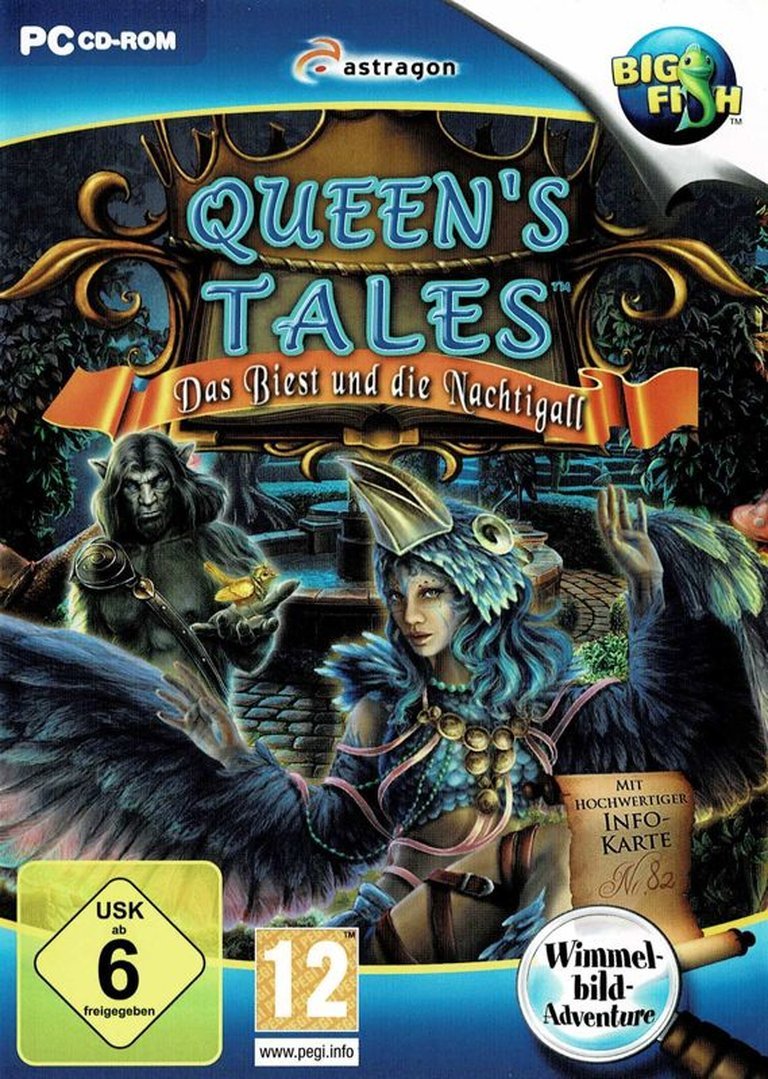

- Release Year: 2014

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Big Fish Games, Inc

- Developer: ERS G-Studio

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

In the fantasy adventure game ‘Queen’s Tales: The Beast and the Nightingale’, the protagonist’s father is accused of theft by a beast after finding a magical nightingale in a castle, resulting in a curse that forces the daughter to take a teleporting ring and embark on a perilous journey. She must solve hidden object puzzles and mini-games across realms populated by dwarves, mermaids, and oracles, while evading a witch, to return to the castle before midnight and save her father from eternal servitude or death.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Queen’s Tales: The Beast and the Nightingale

PC

Queen’s Tales: The Beast and the Nightingale Guides & Walkthroughs

Queen’s Tales: The Beast and the Nightingale Reviews & Reception

gamezebo.com (80/100): Queen’s Tales doesn’t try to break the casual adventure game mold, but it’s still no slouch when it comes to raw entertainment value.

Queen’s Tales: The Beast and the Nightingale: A Solid, if Subservient, Entry in the Casual Adventure Pantheon

Introduction: A Fairy Tale for the Download Generation

In the crowded bazaar of early-2010s casual PC gaming, few formulas were as reliably profitable as the hidden object adventure steeped in fairy tale lore. It was an era defined by the dominance of platforms like Big Fish Games, where narrative was often a secondary concern to the satisfying click of finding a tiny, rendered object against a cluttered backdrop. Into this landscape stepped ERS Game Studios (credited as ERS G-Studio) with Queen’s Tales: The Beast and the Nightingale in 2014. Published by Big Fish Games, this title sought to carve out a niche by weaving a darker, more somber variant of the “Beauty and the Beast” archetype with a unique magical mechanic. This review argues that The Beast and the Nightingale is a competently constructed and thematically cohesive specimen of its genre, successfully integrating its central narrative MacGuffin into its puzzle design to create a consistently engaging, if ultimately formulaic, experience. Its legacy is not one of groundbreaking innovation, but of exemplary execution within the well-worn, yet still popular, confines of the point-and-click hidden object adventure.

Development History & Context: The Assembly Line of Enchantment

To understand Queen’s Tales, one must first understand its studio and publisher. ERS Game Studios, a Romanian developer, was (and remains) a powerhouse for Big Fish Games, churning out numerous titles across series like Dark Parables, Grim Facade, and Phantasmat. Their business model was one of efficient, reliable production. By 2014, the hidden object adventure genre was a mature, saturated market. The technological “constraints” were less about hardware limitations and more about a deliberate design philosophy targeting a specific demographic: primarily older, casual players seeking relaxing, story-driven puzzle experiences on modestly specced Windows PCs (and later, Macs). The game’s system requirements—a Pentium 3 1.0 GHz, 1GB RAM—were minimal even for its time, emphasizing accessibility over graphical spectacle.

The “vision” was clear from the outset: leverage the timeless appeal of European fairy tales (specifically the obscure Grimm variant “The Singing, Springing Lark”) and package it with a suite of mini-games and hidden object scenes (HOPs) that could be enjoyed in short, stress-free sessions. The gaming landscape was one where franchises like Mystery Case Files and Dark Parables set the standard. Queen’s Tales did not arrive to disrupt this landscape but to occupy a familiar and comfortable seat within it. Its 2014 release placed it squarely in the middle of the genre’s peak popularity, and its subsequent inclusion in a Collector’s Edition (released in 2015) and a sequel, Queen’s Tales: Sins of the Past (2016), confirms its commercial success within its intended niche.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Sacrifice, Sorcery, and a Singing Bird

The plot, as summarized on MobyGames, is direct: a father’s impulsive act of kindness (freeing a caged nightingale from an old castle) triggers a curse. A Beast (later revealed to be the Prince of Flowers) grants him a ring and forces a brutal choice: eternal servitude or the surrender of his daughter. The unnamed protagonist (the daughter) chooses the latter, sacrificing her freedom to save her father. She is teleported away, armed only with the ring and a cryptic deadline: she must reach the Beast’s castle by midnight, or her father dies. Her journey is obstructed by the malevolent witch Varga, who employs her corrupted childhood friend Dorian as a pawn to impede her progress.

The narrative is delivered through a framing device: an older queen (implied to be the protagonist) recounting the tale to her daughter, a structure noted by TV Tropes. This adds a layer of nostalgic, almost mythical weight. Thematically, the game explores classic fairy tale motifs:

* Sacrifice and Agency: The heroine’s choice is the engine of the plot, a proactive act of filial love that defines her character.

* The Nature of the Beast: True to its source material, the Beast is a cursed prince, central to the “Beauty and the Beast” trope the game inhabits. The ultimate goal is not merely to reach him but to break his curse, achieved by confronting the source of his enchantment: Varga.

* Corruption and Enslavement: Varga represents the archetypal evil sorceress. Her corruption of Dorian exemplifies the “Brainwashed and Crazy” trope, adding a personal stake and tragic dimension to the heroine’s quest.

* The Power of Nature: The magical nightingale is not just a plot device but a core gameplay mechanic. Its song has the power to make plants “grow, bloom and bear fruit,” a literalized “Fertile Feet” (or rather, song) trope. This beautifully integrates the story’s magic system into the puzzle-solving, making the bird a permanent and relevant fixture in the player’s HUD.

Dialogue is serviceable, moving the plot forward without significant depth. The characters are archetypal but effective: the brave but ordinary heroine, the monstrous-yet-vulnerable Beast, the gleefully wicked Varga, and the pitiable, enslaved Dorian. The story’s simplicity is its strength, allowing the gameplay to remain the focal point.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Well-Oiled Puzzle Machine

Queen’s Tales operates on a classic point-and-click interface. The player navigates between static, beautifully illustrated screens, interacting with hotspots to collect inventory items and trigger events. The core gameplay loop is: arrive at scene -> observe clues/notes -> find hidden objects (HOPs) -> use collected items on other items or locations -> solve mini-game -> progress.

Hidden Object Scenes: These are the game’s bread and butter. As detailed in the walkthroughs from Big Fish Games and Casual Game Guides, lists of items appear at the bottom. Items are cleverly hidden within the scene’s clutter, with some requiring an extra step (color-coded in green in some versions). A key innovation is the option to swap a HOP for a match-3 mini-game via a button in the top-left corner. This “Sliding Scale of Gameplay and Story Integration” is a crucial accessibility feature, catering to player preference without breaking the narrative flow.

The Nightingale Mechanic: This is the game’s signature touch. Once obtained in Chapter 1, the nightingale perches in the bottom-left HUD. Clicking it allows the player to use its magic on designated plants or fungi throughout the game world, causing them to grow and yield new items (e.g., a flower, a berry, a sapling). This is not a cosmetic effect but a recurring puzzle solution, directly tying the central story element to the gameplay. It’s a simple but highly effective integration that makes the player feel connected to the nightingale’s magical properties.

Mini-Games: The game is packed with them, serving as gates between major areas or solutions within HOPs. Types include:

* Sliding/Rotating Puzzles: Restoring portraits, aligning symbols, rotating tower panels.

* Logic Puzzles: The “vial mini-game” (tilting a screen to fill vials to a line), the “puffball untangling” game, the “door pattern” puzzle using tiles.

* Navigation Puzzles: The early ship steering puzzle using a wind rose.

* Collection & Construction: Finding parts (puzzle parts, sphere parts, symbol tiles) to assemble objects that unlock new areas.

These mini-games are generally medium difficulty, with solutions that can be logically deduced. The walkthroughs reveal their solutions are often deterministic (e.g., specific button presses for the vials), suggesting they are more about pattern recognition than pure guesswork.

Inventory & Progression: Inventory is housed at the bottom of the screen and can be locked open (a helpful tip from the walkthrough). Items are frequently used screens or even chapters later, encouraging careful observation and note-taking (the in-game Journal is vital). The map becomes available early (Chapter 2) and is essential for fast travel between the game’s interconnected realms: the forest edge, the oracle’s hut, Varga’s den, and the castle grounds.

Difficulty & Pacing: The game offers four difficulty levels: Casual (with tutorials, sparkles, slower hint recharge), Advanced, Hard (no tips, faster hint recharge, more complex puzzles), and Custom. This allows players to tailor the experience. The * narrative deadline (midnight)* creates a sense of urgency but has no actual gameplay consequence; it is a purely atmospheric pressure. The pacing is deliberate, with eight substantial chapters, ensuring a lengthy experience for a hidden object game.

Flaws: The systems are robust but not revolutionary. Some item combinations can feel contrived (e.g., using a tiny toy crossbow to retrieve a sapphire), and the backtracking between areas can become tedious. The “time pressure” is ultimately an empty threat.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Consistently Enchanting Visual Tapestry

The game’s art direction is its most consistently praised element. Screenshots and descriptions reveal a style of illustrated realism—detailed, painterly scenes that feel ripped from a high-quality storybook. The settings are classic fantasy: a storm-lashed castle, an enchanted forest with talking mushrooms, a mermaid’s aquatic grotto, a witch’s alchemy-laden den, and the gothic halls of the castle itself. Each location has a distinct color palette and mood, from the cool blues and greens of the water realms to the warm, ominous reds and browns of Varga’s lair. This visual cohesion successfully builds a world that feels magical and cohesive.

The sound design is less documented in the sources, but the Gamezebo review mentions “cringe-worthy voice acting,” a common critique in many Big Fish/ERS titles where budget constraints often lead to uneven vocal performances. The background music is likely typical of the genre: melodic, moody, and unobtrusive, designed to enhance the atmospheric immersion without demanding attention. The nighthingale’s song—a key auditory element—is presumably a simple, enchanting chime that plays when the mechanic is used.

Atmosphere is paramount. The game embraces a dark fairy tale aesthetic. There’s a sense of ancient magic, lurking danger (from Varga and the Beast initially), and melancholic beauty. The “Beast” is genuinely imposing in his early appearances, and Varga’s interventions are unsettling. This isn’t a Disneyfied world; it’s one where pacts are made under duress and curses are a constant threat. The art and sound work in tandem to sell this tone, making the exploration of each new scene a visually rewarding experience.

Reception & Legacy: A Niche Success, Not a Landmark

Critical reception for Queen’s Tales was limited but generally positive. Metacritic shows no critic reviews and a user score pending from too few ratings, indicative of its niche, non-mainstream status. The more telling data point is Steam, where the Collector’s Edition holds a perfect 100/100 Player Score from 5 reviews—a small but thrilled sample. The most comprehensive professional take comes from Gamezebo’s John Bardinelli, who awarded it 80/100. He praised its “great setting with imaginative artwork,” “item-heavy scenery,” and the effective use of the nightingale mechanic. His criticisms were standard for the genre: “cringe worthy voice acting” and a lack of gameplay surprises (“No real surprises in terms of gameplay or puzzles”). This encapsulates the critical consensus: it does what it sets out to do very well, but it doesn’t transcend the formula.

Commercially, its success is evidenced by its inclusion in the Collector’s Edition format (a Big Fish staple with bonus content like an extra chapter and art gallery) and the production of a direct sequel, Queen’s Tales: Sins of the Past (2016). It clearly found its audience among casual adventure aficionados. However, its impact on the industry as a whole was negligible. It did not popularize a new mechanic or trend. Instead, its legacy is that of a textbook example of a well-executed hidden object adventure in the genre’s late golden age.

Its influence is seen in its peers, not its successors. It sits comfortably alongside series like Dark Parables (which also adapted fairy tales with intricate dollhouse-like rewards) and Mystery Legends: Beauty and the Beast (a more direct adaptation of the French tale). It represents the refinement, not the evolution, of the genre. As digital storefronts like Steam and mobile app stores began to dominate post-2014, the traditional Big Fish-style downloadable adventure began to wane in cultural prominence. Queen’s Tales is thus a culmination of a specific era: the high-point of the PC-focused, narrative-light, puzzle-heavy hidden object game.

Conclusion: A Worthy Tale in the Anthology

Queen’s Tales: The Beast and the Nightingale is not a hidden gem—it was a reliably sold product in its day. Nor is it a forgotten failure—it spawned a sequel and enjoys a small, devoted fanbase. It is, instead, a paradigm of competent genre craft. Its narrative, while simple, is integrated with its gameplay via the brilliant nightingale mechanic, creating a sense of cohesive design often missing in titles where the story is merely a veneer for object hunts. Its art is consistently beautiful, its puzzles logical and satisfying, and its pacing deliberate.

Its flaws are the flaws of its genre: serviceable-at-best voice acting, a lack of genuine narrative complexity, and gameplay loops that, while polished, are familiar. For the modern historian, the game is a vital artifact. It demonstrates the peak of a design philosophy targeted at a specific, underserved audience. For the player in 2025, it remains a highly recommended experience for fans of classic hidden object adventures seeking a dark, atmospheric fairy tale with a genuinely clever central mechanic. It may not rewrite the rulebook, but within its own well-defined kingdom, it reigns as a perfectly adequate, often enchanting, monarch.

Final Verdict: B+ (85/100) – A impeccably crafted example of the early-2010s hidden object adventure. Its strengths in atmosphere, visual design, and core mechanic integration outweigh its formulaic nature and vocal shortcomings. Essential for genre enthusiasts, a pleasant surprise for curious newcomers.