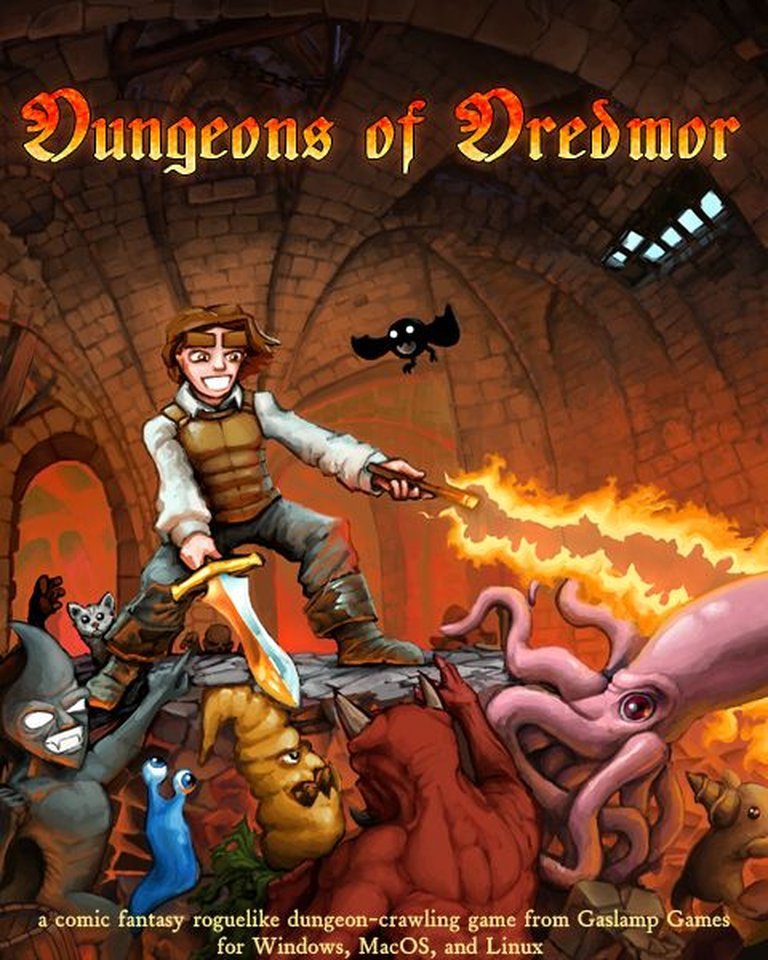

- Release Year: 2011

- Platforms: Linux, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Gaslamp Games, Inc.

- Developer: Gaslamp Games, Inc.

- Genre: RPG

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Alchemy, Blacksmithing, Crafting, Goldsmithing, Magic, Randomly generated dungeons, Survival cooking, Turn-based combat

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 79/100

Description

Dungeons of Dredmor is a role-playing dungeon hack that modernizes classic Roguelike gameplay with a fully graphical, point-and-click interface. Set in a fantasy world, players navigate randomly generated dungeons, engaging in medieval-style combat, scavenging for treasure, crafting items from found materials, and utilizing a mana-powered magic system to battle unique monsters and ultimately face the Dark Lord Dredmor.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Dungeons of Dredmor

PC

Dungeons of Dredmor Guides & Walkthroughs

Dungeons of Dredmor Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (79/100): There is a truly massive amount of game here for the $5 asking price, and Gaslamp Games has clearly set Dredmor apart from the crowd.

ign.com : Casual meets brutal in this delicious indie roguelike.

Dungeons of Dredmor Cheats & Codes

PC

Enable cheat mode by adding -debug-flag to Steam launch options, then press the following case-sensitive keys during gameplay.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| [Plus] | Faster animations |

| L | Full map |

| P | Go down a dungeon level |

| b | Go to pocket dimension |

| p | Go up a dungeon level |

| l | Level up 15 times |

| [Minus] | Slower animations |

| I | Spawn random loot based on dungeon level |

Dungeons of Dredmor: A Definitive Analysis of a Roguelike Landmark

Introduction: The Dungeon Awaits (And So Do You)

In the vast pantheon of video games, few titles capture the spirit of chaotic, rewarding, and brutally honest fun quite like Dungeons of Dredmor. Released in 2011 by the then-nascent Gaslamp Games, this title did not merely enter the roguelike arena; it cartwheelelled in, threw a pie in the face of genre orthodoxy, and then challenged the entire room to a duel with a chainsaw-launched lutefisk. At its core, Dungeons of Dredmor is a masterclass in accessible complexity, a game that wraps the impenetrable depth of classic ASCII roguelikes in a package of hand-drawn charm, sidesplitting humor, and systems so interwoven they feel alive. This review argues that Dungeons of Dredmor’s true legacy lies not in its mechanical innovations per se, but in its profound, almost alchemical, synthesis of tone and design. It successfully decoupled the “hardcore” reputation of the roguelike from the grim, oppressive atmosphere of its predecessors, replacing it with a self-aware, joke-laden, and deeply inventive world that invited players to die repeatedly—not out of frustration, but out of a desperate, gleeful curiosity to see what absurdity the next floor would throw at them. It is, simultaneously, a loving parody of fantasy tropes and a genuinely profound piece of game design, a title that understood that the joy of discovery is magnified when paired with a wink.

Development History & Context: From Basement Dreams to Steam Stardom

The story of Dungeons of Dredmor is intrinsically the story of Gaslamp Games’ messy, hilarious, and ultimately triumphant genesis. The studio’s origins are a testament to the “try anything” ethos of the late-2000s indie boom, birthed not in a polished office but in the “German bondange dungeon”—a wood-paneled, pleather-wrapped basement office in Esquimalt, British Columbia, that reeked of old coffee and epoxy.

The Failed Pivot and The Accidental Savior: The project that would become Dredmor was not the team’s first ambition. As recounted by artist and co-founder David Baumgart in his essential 2021 memoir, the original endeavor was Clockwork Fantasia—a wildly over-ambitious hybrid of Final Fantasy Tactics and steampunk, featuring dynamic liquid physics and 3D landscapes. The team, comprised of programmer Nicholas Vining, Daniel Jacobsen, a 3D artist named Jesse, and later Baumgart, had no formal project management, no business entity, and unclear roles. Clockwork Fantasia collapsed under its own weight, a victim of “no one having legitimate professional experience in the development of actual software.” Jesse departed for Japan, leaving behind erotic Sonic fanart and two yams. The project stalled, invoices went unpaid, and Baumgart prepared to move on.

The savior was an “immature build” Vining had been hacking on since 2006: a rudimentary, humorless roguelike codebase internally dubbed “Project Orion” or “Heroes Wanted.” Its key asset was a complete set of animations by Bryan Rathman (later of Blizzard fame). The art was goofy—featuring mustachioed brick demons, drill-nosed bird monsters from Disgaea, and a hero resembling Monkey Island‘s Guybrush Threepwood. The plan was simple: polish this rough gem in a couple of months, ship it, make some cash, and return to Clockwork Fantasia. This plan took three years.

The Crucible of Constraints: The development period (roughly 2008-2011) was defined by scarcity. The team worked with “an ancient sprite editing program you pirated from somewhere like ten years ago” and “weird ancient semi-legal program[s]” for particle effects. Baumgart, initially contracted solely as an artist, found himself assuming myriad roles—coder, designer, writer, documentarian—but was consistently pigeonholed as “just the artist,” a dynamic that limited his credited influence. The pivotal moment came when Baumgart, ready to quit, was propositioned with equal ownership. “That was the one condition that would keep me onboard,” he wrote. This informal partnership, solidified around 2009-2010, was the final piece. The team decamped from the basement to Vancouver, and with a shared, desperate stake in the outcome, they began the monumental task of turning a quirky prototype into a coherent game.

The 2011 Indie Landscape: Dungeons of Dredmor arrived in a sweet spot for indie roguelikes. Spelunky (2008/2012) had proven the commercial viability of the “modern roguelike,” while The Binding of Isaac (2011) demonstrated the power of combinatorial item horror. The genre was shedding its ASCII shell, but most graphical attempts were either serious (Dungeons of Dredmor’s spiritual cousin, Dungeons of Dredmor’s spiritual cousin, Dungeons of Dredmor’s spiritual cousin) or overly simplistic. Gaslamp’s offering was uniquely positioned: it was undeniably a roguelike—turn-based, permadeath-optional, procedurally generated—but presented with the confidence of a finished product and the personality of a celebrated comedy troupe. Its $4.99-$7.99 price point on Steam was a liberation, framing it not as a niche product but as a no-brainer impulse buy for any curious gamer.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Prophecy, Parody, and Pointless Sidequests

Dungeons of Dredmor’s narrative is a masterclass in “affectionate parody,” using a bare-bones premise as a clothesline for a staggering density of jokes, references, and world-building gags that elevate it from backdrop to a core component of the gameplay experience.

The Plot (Such As It Is): The setup is pure, distilled fantasy trope: “Long ago, the Dark Lord Dredmor was bound in the darkest dungeons beneath the earth by great and mighty heroes. Centuries later, the magical bonds that hold him in place are loosening…” The land cries for a hero. Unfortunately, it gets you. This immediate subversion—”What they have, unfortunately, is you…”—sets the tone. The player is not the Chosen One; they are the Available One, a schmuck thrust into a cosmic-scale dungeon with no training, no prophecy, and a likely epitaph waiting to be written. The goal, “killing Dredmor,” is presented as a distant, almost academic objective, as the developers themselves admit: “the objective is more often to see how far one can get before dying.”

The Pantheon of Absurdity: The world-building is delivered not through exposition but through item descriptions, monster epithets, and godly interjections. The pantheon is a highlight:

* Inconsequentia, Goddess of Pointless Sidequests: Her statues offer procedurally generated fetch/kill quests that are deliberately trivial or bizarre, embodying the “why am I doing this?” feeling of many RPG quests, but celebrating it.

* The Lutefisk God: A deity whose primary symbol is the famously reviled Nordic dish. Lutefisk is an inedible consumable that mocks you in its tooltip. Sacrificing it to the Lutefisk God is a primary method of acquiring powerful artifacts, a perfect marriage of gameplay mechanic (sacrifice) and joke (the sacrifice is of something universally considered terrible).

* Vlad Digula: The Greater-Scope Villain trapped in Diggle Hell, a nod to the cyclical nature of these games and a source of endgame terror in the Wizardlands expansion.

Dialogue & Flavor Text as the Lifeblood: The game’s true narrative engine is its flavor text. Every item—from a “Bucket Helmet” to a “Dire Sandwich”—has a description. Every monster has a plurality of possible epitaphs for your gravestone (“Killed by a Thrusty. That’s a new one.”). Every skill tree is narrated with a specific, ridiculous voice:

* Communism: Delivered in a “silly 1980s-style stereotypical Russian accent,” abilities like “Guerrilla Attack” and “Popular Front” mix Klingon-esque grammar with revolutionary jargon.

* Mathemagic: Skills are named after equations and theorems (Cauchy-Schwarz, Banach-Tarski), with descriptions that are either earnestly mystic or dryly academic (“You have factored the prime polynomial of their soul.”).

* Warlockery: Described as “wizards that really wish they were warriors… Anything but wizards, really.” Its abilities involve channeling mana into physical strikes.

* Archaeology: An Indiana Jones pastiche, starting you with a fedora. One skill, “This Translation is All Wrong!,” lets you re-roll item enchantments, a direct meta-commentary on players’ obsession with perfect loot.

Underlying Themes: Beneath the puns, several themes emerge:

1. Subversion of the Hero’s Journey: You are not special. Your skills are not a calling but a haphazard collection. Dredmor is not a monologuing villain but an entity you might defeat by accident while trying to steal his boots.

2. The Absurdity of Systems: The game constantly winks at its own artificiality. The “Encogging” encrustment is literally “cogwheels glued on.” The “Razor Sword For Her” is “perfectly identical… except it’s pink and costs twice as much.” These are jokes about game design clichés that the game itself then implements as functional mechanics.

3. Embracing the Random: The procedural generation isn’t just a technical tool; it’s a philosophical stance. The joy comes from the unexpected synergy—finding a “Bolt of Mass Destruction” (a nuke crossbow bolt) on floor 1, or combining a “Luftwaffles” item (a pastry that summons explosive, angry pastry chefs) with a “Muscle Diggle” pet. The narrative is emergent, born from the clash of systems and the RNG.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Symphony of Synergy and Sin

Dungeons of Dredmor’s genius is its “combinatorial explosion” of systems, where each mechanic feeds into and amplifies the others, creating a gameplay ecosystem that feels both deeply strategic and chaotically unpredictable.

Character Creation: The Skill-Based “Classless” System: There are no traditional classes. Instead, you select * seven skill trees* from a pool of over 20, organized into Warrior (weapon-focused), Rogue (utility, theft, traps), and Wizard (magic, crafting) categories. This is the game’s primary source of build diversity. Want a Vampiric Communist Demonologist who drinks booze for mana, summons demons, and uses Marxist rhetoric? You can. A Clockwork Knight Archaeologist in Powered Armor wielding a jetpack and a chainsaw? Absolutely. The skill trees have 4-8 tiers, with each level granting a new ability. The learning curve is steep but rewarding; understanding that “Fungal Arts” grows mushrooms on corpses that can heal or buff you, while “Golemancy” lets you build mustache golems from cutlery, is key to survival.

Core Loop & Progression: The loop is classic roguelike: descend floor-by-floor (1-13+ normally), fight monsters, collect loot, manage inventory, and level up. Progression is dual-track:

1. Leveling: Grants skill points to upgrade your chosen trees. The level cap is effectively 50, but “Empty Levels” (gaining XP with maxed skills) are still valuable for high-score chasing.

2. Gear & Crafting: This is where the game’s depth truly sings. Four major crafting skills (Alchemy, Smithing, Tinkering, Wandcrafting) and later Encrustings (from the Wizardlands expansion) allow you to transform base items into godlike artifacts. A rusty dagger can become a “Moravician Bushdagger” with fractal blades that recursion-stab. A plastic ring can be encrusted with steam vents and gears to boost damage. The crafting system is portable—you can smith on the go—and governed by recipes often hidden in bookshelves (a design fix to prevent wiki-spoiling). The joy of discovering a recipe through experimentation or a lucky book find is immense.

Combat & Damage: Turn-based and grid-based. Positioning, door-slamming, and kiting are vital. The damage type system is gloriously baroque. Beyond standard Slashing/Piercing/Crushing, you have:

* Conflagratory (Fire), Hyperborean (Ice), Voltaic (Electric)

* Righteous (Holy), Necromantic (Evil), Putrefying (Undead)

* Aetheral, Asphyxiative, Existential (which “may or may not actually exist”).

Resistances and vulnerabilities are critical. A build weak to Necromantic damage will crumble in the Crypts.

Inventory & UI – The Achilles’ Heel: This is the most consistent criticism. The inventory management is a chore. With hundreds of stackable items (potions, food, crafting mats, ammo), organizing your bags is a constant mini-game. The UI, while functional, can feel cramped, especially at higher resolutions—a problem noted by Rock, Paper, Shotgun. The “click hand to pick up, click eye to examine” interface is a conscious throwback to King’s Quest, but can feel sluggish. However, the game’s built-in autosort and trash functions are necessities many players learn to rely on.

Difficulty & The “True” Objective: The three difficulties—Elvishly Easy, Dwarven Moderation, Going Rogue—adjust monster HP, spawn rates, and regeneration. The “No Time To Grind?” option creates smaller, XP-rich floors. But the soul of the game is in its permadeath (toggleable) and the meta-game of high scores. Dying is inevitable. The epitaph system (“Killed by a Mustache Golem while attempting to eat a cheese sandwich”) turns failure into comedy. The real boss is the Random Number God. Finding a “Bolt of Mass Destruction” early can trivialize floor 1, while a run starved of food or resistances can end on floor 3. This volatility is a feature, not a bug, for its intended audience.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Pixel-Perfect Parody

The aesthetic of Dungeons of Dredmor is the visual and auditory manifestation of its thematic heart: a loving, detailed, and utterly ludicrous send-up of fantasy.

Art Direction & Visuals: Baumgart’s task was to unify Rathman’s quirky animations and Vining’s primitive placeholders into a coherent style. The result is a hand-drawn, pixel-art aesthetic that feels both retro and meticulously detailed. The environments—wood-paneled “German bondage dungeon” tilesets, brick goblin warrens, glittering dwarven vaults—are simple but evocative. Monster designs are the star: the drill-nosed Diggles (in countless palette-swapped variants: Enraged, Hungry, Arch-Diggle), the Mustache Golems, the Thrusties (sentient, murderous stalagmites), the Swarmies (a cloud of angry bees). They walk with a bouncy, idle animation that makes the dungeon feel alive and silly. The player character is a deliberately generic, big-eyebrowed avatar—a silent placeholder that contrasts with the verbose world, emphasizing that you are the straight man in this comedy of errors.

Sound Design & Music: Composer Matthew Steele (who also provided sound effects and the iconic announcer voice) delivered a score that perfectly matches the tone. Tracks like “The Forsaken” use an ominous pipe organ that swells into a harp and strings, creating a mock-epic feel. “Death Walks Among You” builds tension with that organ arrival. The sound effects are punchy and satisfying—the clang of a shield block, the squelch of a fungal explosion, the tinny boop of a lockpick. The announcer’s dry delivery of events (“Heroic Vandalism!” after smashing a statue) is a constant source of charm.

Atmosphere & Cohesion: Where the game truly shines is in the synergy between its joke systems and its core mechanics. The “Lutefisk God” isn’t just a reference; it’s a functional crafting/sacrifice system. The “Communist” skill isn’t just a voice; its abilities (“Hire Contractor” to temporarily convert a monster) are powerful and thematically consistent. The world doesn’t feel like a parody pasted on a serious roguelike; it feels like a coherent, absurd universe where the laws of physics bend to the punchline. This cohesion makes the humor land harder because it’s in the gameplay, not just in text boxes.

Reception & Legacy: The Indie Darling That Could

Critical Reception at Launch (2011): Dungeons of Dredmor was met with broadly positive reviews, holding a 79/100 on Metacritic and 79.00% on GameRankings. Critics consistently praised its:

* Depth & Replayability: IGN (8.5/10) highlighted the “voluminous depths” of loot and “intriguing character skills to tinker with.”

* Humor: Ars Technica and Game Informer specifically called out its “wicked sense of humor” and “lighthearted” tone as key differentiators.

* Accessibility: GamesRadar and Eurogamer noted how difficulty sliders and permadeath toggles made it a viable entry point for genre newcomers (“a ‘my first roguelike'”).

* Value: Almost every review mentioned the staggering amount of content for under $10.

Common Criticisms: The flaws were also consistent:

* Inventory Management: Cited by GamesRadar and RPGamer as an “absolute chore.”

* Interface Issues: Rock, Paper, Shotgun and Bit-Tech noted microscopic UI at high resolutions and sometimes-clunky controls, though the former conceded, “it’s a £3 game. For the sheer mass of ideas… it’s pretty damn churlish to demand anything else.”

* Inconsistent Balance: GamePro and HonestGamers mentioned swingy difficulty—some runs are easy with the right item, others are hopeless—and a perceived exhaustion of novelty after a few floors.

Awards & Commercial Success: The crowning achievement was being named PC Gamer US’s “Indie Game of the Year” for 2011. It was a significant commercial success on Steam, recouping its minimal development costs quickly and funding three official DLC packs: Realm of the Diggle Gods (2011), You Have To Name The Expansion Pack (2012—which included mods and let you rename the expansion), and Conquest of the Wizardlands (2012). It also gained robust Steam Workshop support, fostering a vibrant modding community that added new skills, items, and balance overhauls.

Evolution of Reputation & Industry Influence: Over time, Dredmor’s reputation has solidified into cult classic status. It is now often cited as a pivotal bridge between traditional roguelikes (like DCSS or Nethack) and the modern “roguelite” boom. Its success proved that a game could be brutally deep, mechanically complex, and hilariously funny without being impenetrable or grimdark. It directly influenced a generation of indie developers to embrace tone as a core design pillar. Games like Wizard of Legend (fast-paced, combo-heavy) or Streets of Rogue (absurd item interactions) share its DNA of systemic humor. However, it did not spawn a direct clone; its particular alchemy of specific humor, crafting depth, and skill-system freedom remains uniquely Dredmor.

Conclusion: The Endless, Hilarious Descent

Dungeons of Dredmor is a landmark of indie game design. It is not the most polished, the most balanced, or the most revolutionary in any single mechanical way. Its inventory system is a notorious headache. Its UI shows its budget. Its difficulty can feel capricious.

Yet, it is a masterpiece of holistic design. It is a game where every system—from the six whimsical core stats (Burliness, Nimbleness, Sagacity, Caddishness, Savvy, Stubborness) to the Lutefisk God—serves a unified vision of playful, punishing, and profound adventure. It respects players’ intelligence by letting them discover combos and recipes, but rewards them with a universe that laughs with them, not at them, when those combos backfire (and they will). It understands that the essence of a roguelike is the loop: the descent, the discovery, the build-crafting, the glorious, stupid death. By wrapping that loop in a package of relentless wit and charming, hand-crafted assets, Gaslamp Games made the genre feel welcoming without diluting its core tension.

Its place in history is secure. It is the game that taught a generation that “hardcore” doesn’t have to mean “joyless.” It is the title that asked, “What if the Dark Lord’s greatest weapon was just… really bad lutefisk?” and then built a entire, captivating world around the answer. To play Dungeons of Dredmor is to descend into a dungeon that is as smart as it is silly, as cruel as it is kind, and as endlessly replayable as any true classic. The dungeon of Dredmor awaits. Are you ready for it? (Spoiler: You’re not. But you’ll have a blast trying anyway.)

Final Verdict: 9/10 – A quintessential, timeless indie roguelike where flavor is substance, and death is just the setup for the next joke.