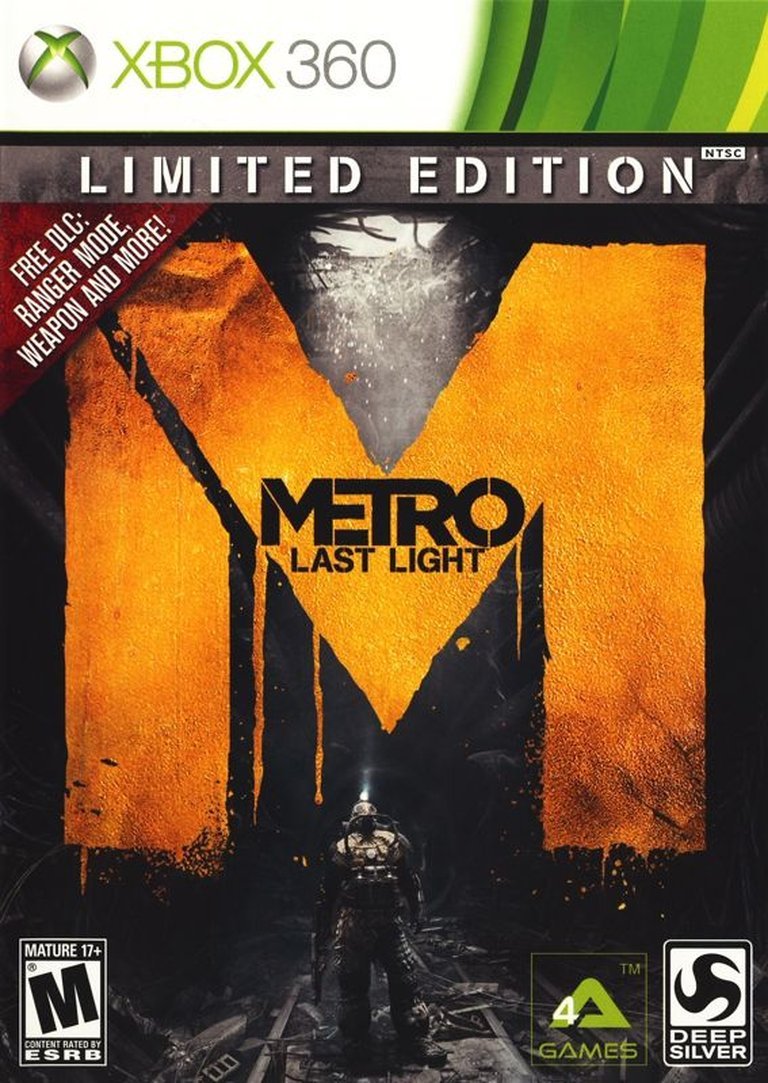

- Release Year: 2013

- Platforms: PlayStation 3, Windows, Xbox 360

- Publisher: Koch Media GmbH

- Genre: Compilation, Special edition

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Average Score: 82/100

Description

Metro: Last Light is a first-person shooter survival horror game set in the post-apocalyptic Moscow Metro after a devastating nuclear war. Players assume the role of Artyom, a young soldier tasked with locating the mysterious Dark Ones, exploring both the hazardous metro tunnels and the irradiated surface while battling mutated monsters and competing human factions in a tense, atmospheric struggle for survival.

Metro: Last Light (Limited Edition) Guides & Walkthroughs

Metro: Last Light (Limited Edition) Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (82/100): A great antidote for brogamer oriented western shooters.

ign.com : It undoubtedly rewards methodical players.

trustedreviews.com : This isn’t your usual post-apocalyptic nightmare, but a distinctly Russian one,grim and strange, yet balanced by pockets of warmth and sardonic humour.

Metro: Last Light (Limited Edition) Cheats & Codes

Metro: Last Light for PS3, Xbox 360, and PC

Enter codes at game start or in-game as specified in the source text.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| 52782 | Get a variety of weapons with unlimited ammo |

| 51197 | Unlock the extra survival mode |

| 53198 | Unlock all upgrades |

| 54991 | Get an extra life |

| 55992 | Get a gas mask |

| thedarkones | Have infinite resistance |

| bulletbounty | Have infinite ammunition |

| allgunsblazing | Have all the weapons available |

| bulletsplosion | Increase the amount of ammo |

| noseeum | Enable night vision |

Metro: Last Light (Limited Edition): A Symphony of Despair and Redemption in the Ruins of Moscow

Introduction: The Last Light Pierces the Darkness

In the pantheon of post-apocalyptic video games, few titles capture theomycological dread, scarce-resource tension, and profound moral ambiguity of the nuclear wasteland with the unflinching fidelity of Metro: Last Light. Released in 2013 by the embattled Ukrainian studio 4A Games, this sequel to the critically adored Metro 2033 arrived not merely as a continuation, but as a refined manifesto of a specific, brutally realistic vision of the end times. It is a game that understands that the true horror lies not in the mutants skittering in the dark, but in the flickering humanity of the survivors and the weight of a single, catastrophic decision. The Limited Edition, with its infamous inclusion of “Ranger Mode” as a pre-order bonus, became a flashpoint in the ongoing conversation about player agency, difficulty as artistry, and the monetization of core experiences. This review will argue that Metro: Last Light stands as a monumental, if imperfect, achievement—a game that leveraged its developer’s dire circumstances to forge one of the most atmospheric, mechanically distinctive, and thematically resonant first-person shooters of its generation. It is a flawed masterpiece that successfully builds upon its predecessor’s foundation, refining gameplay while deepening its philosophical inquiry, ultimately cementing the Metro series as a cornerstone of immersive, narrative-driven design.

Development History & Context: Forged in the Frozen Shadows of THQ

The story of Metro: Last Light is inextricably linked to the tempestuous final days of its original publisher, THQ. Developed by the roughly 80-person team at 4A Games in Kyiv, Ukraine, the project was born from a desire to correct the perceived “flawed masterpiece” status of Metro 2033. As detailed in post-mortems from former THQ President Jason Rubin, the development conditions were nothing short of brutal: a freezing office with frequent power outages, extreme crowding, and a budget Rubin claimed was a mere 10% of comparable AAA projects. The team reportedly had to smuggle computer equipment to avoid corrupt customs officials. This environment of scarcity and persistence directly mirrored the game’s own themes of scavenging and survival.

Franchise creator Dmitry Glukhovsky returned not to adapt his novel Metro 2034, which the developers felt was an “art-house thriller” incompatible with a game adaptation, but to pen the game’s dialogue and main story outline. This separation from the source novel allowed 4A to craft a direct sequel to the game’s canon, specifically choosing the “bad” ending of 2033—where Artyom destroys the Dark Ones—as its starting point. This narrative decision frames the entire sequel with a profound sense of guilt and a quest for atonement.

The game’s development was nearly derailed by THQ’s bankruptcy in late 2012. After an auction, Koch Media (via its Deep Silver label) acquired the franchise for $5.9 million. This transition, while fraught with uncertainty, ultimately saved the project; Koch was familiar with 4A from their work on S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Clear Sky and recognized the title’s potential in its nearly complete state. The team’s goal was clear: to create an experience that was the polar opposite of the linear, multiplayer-focused Call of Duty model. As Huw Beynon, head of communications for THQ then Deep Silver, stated, they aimed to “rekindle memories of Half-Life 2” with a game where “all the enemy encounters… are designed to be different from each other” and “narrative-driven.”

A planned competitive multiplayer mode was scrapped to double down on this single-player vision. The team also made a deliberate choice not to “westernize” the franchise, instead overhauling controls for accessibility while preserving the Eastern European, nihilistic soul. The most infamous development decision was the creation of Ranger Mode. Born from the team’s own hardcore sensibilities and a desire to strip away all “gamey” interfaces, it was marketed as “the way [the game] was meant to be played.” Its packaging as a pre-order exclusive for the Limited Edition—which also included a modified rifle and extra currency—sparked immediate controversy, setting a precedent for “definitive” editions locked behind pre-orders. Technically, the game was powered by the in-house 4A Engine, with significant improvements to lighting, destruction, and a more varied color palette compared to the bleak monochrome of its predecessor.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Weight of a Ghost

Metro: Last Light is a narrative of profound consequence, set in 2034, one year after Artyom’s missile strike against the Dark Ones. The story is a masterclass in leveraging sequel momentum to explore the psychological fallout of player choice from the first game. Artyom, now a full Ranger of the Order, is a “silent protagonist” plagued by nightmares and haunted by the specter of genocide. The central Mcguffin is not a weapon, but a survivor: a single, child-like Dark One.

The plot is a complex web of espionage and factional warfare, a departure from the more spiritual threat of the first game. The discovery of the D6 military bunker—a pre-war fortress—ignites a three-way cold war between the Soviet Red Line, the fascist Fourth Reich, and the neutral Hansa, all coveting its rumored riches. The Rangers, holding D6, become the target. The narrative brilliance lies in its subversion of the “Big Bad”: the Reich’s Führer is a sideshow. The true antagonist is General Korbut of the Red Line, a cunning strategist orchestrating a false-flag bioweapon attack to justify a unification war and seize D6’s actual secret: stockpiles of engineered Ebola virus.

Key characters are etched in moral grey:

* Artyom: His arc is one of redemptive pacifism. His psychic link with the Dark Ones, established as a child, positions him as the only being who can bridge the species. His silent journey is internal, his actions defined by subtle karma choices (sparing enemies, listening to NPC conversations, rescuing prisoners) rather than spoken promises.

* Anna: Miller’s daughter and a sniper, she embodies the harsh practicality of the Metro. Her relationship with Artyom, from icy professional to intimate companion forged in a quarantine cell, is a rare beacon of human connection.

* Pavel Morozov: A tour de force of narrative betrayal. Presented as a charming, heroic Communist comrade who helps Artyom escape the Reich, his reveal as Korbut’s dragon and master manipulator (“All for one… and one for all”) is a crushing blow. His name is a deliberate Shout-Out to the infamous Soviet child-traitor, foreshadowing his perfidy.

* Khan: The mystical wanderer serves as the game’s philosophical compass, constantly urging moral high ground and representing the spiritual undercurrent of the series.

* The Baby Dark One: The ultimate Morality Pet. Its presentation as a vulnerable child, capable of projecting human-like illusions, forces the player to confront the monsters they created. Its psychic ability to see “intent as color” (red to green) externalizes the game’s moral calculus.

The thematic core is redemption and the cycle of violence. Glukhovsky and 4A explore whether a species capable of genocide can earn a second chance. The karma system, while opaque, is the game’s mechanical heart. It culminates in two endings:

1. The “Sacrifice” Ending (Bad): Artyom, convinced the Dark Ones are an existential threat, detonates D6, killing himself, the remaining Rangers, and the Red Line army. Anna is left to tell their child of his bravery—a悲劇 of noble failure.

2. The “Redemption” Ending (Good/Canonical): Artyom is stopped by the Baby Dark One. The awakened adult Dark Ones use their psychic powers to induce mass suicide among Korbut’s troops—a quiet, horrifying justice. Artyom dubs the child “the last light of hope.” This ending posits that hope is not in human fists, but in an external, forgiving grace.

The narrative is flawlessly paced, weaving personal vignettes (the haunted dead city logs, the conversations in stations) into the main plot. The flashbacks—particularly the childhood memory of being saved by a Dark One and the shared hallucination in the crashing plane—are not mere exposition but visceral, emotional gut-punches that re-contextualize Artyom’s entire journey. It is a story that understands its predecessor’s legacy and dares to wrestle with its darkest implications.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Survival, Scarcity, and Subtlety

Metro: Last Light is a first-person shooter that subverts genre conventions at every turn. Its core loop is a tense triad of Scavenge, Survive, Strike.

The Economy of Lead: The signature bullet economy returns, refined. Pre-war military-grade ammunition (MGR) is the universal currency. Crucially, the game provides better early-game explanation, but the fundamental tension remains: fire a斯特林式 (Stirling) round of your precious MGR in a firefight, and you are literally shooting money. Lower-quality Metro-manufactured ammo (pistol, assault rifle, shotgun) is for fighting; MGR is for trading, buying better weapons, attachments, and filters. This creates a constant, palpable calculus. In Ranger Mode, MGR is the only ammo type available for purchase, and all caps are drastically reduced, making every bullet a momentous decision.

Weapon Customization & Loadout: The three-weapon slot system (reduced to two in Ranger Mode) allows unparalleled freedom. Any firearm—from a silenced revolver to a pneumatic Tikhar or a miniflamethrower—can be slotted. Weapons are highly modular with scopes, silencers, extended mags, and barrel attachments. This system encourages personal playstyle: a stealthy Ranger might carry a silenced revolver, a Valve rifle, and a Duplet shotgun; an action-oriented player might opt for an RPK-74 light machine gun. New additions like the Bastard (a high-velocity, overheating assault rifle) and the Preved (a ludicrously powerful anti-materiel rifle) offer distinct tactical niches.

Stealth & Non-Lethal Play: Stealth is no longer a cumbersome afterthought. The watch displays a visibility meter (green/red), and darkness is a powerful ally. Enemies have multi-tiered alertness states. The introduction of a silent melee takedown (a brutal, single-hit knockout with the trench knife) is transformative. It allows for a true Pacifist Run on many levels—not by avoiding conflict, but by silently neutralizing threats. This is not just a stealth option; it is often the optimal survival strategy, conserving ammunition and maintaining the coveted “good” karma. The AI, while still occasionally foolish (guards investigating a broken lightbulb), is more responsive than in 2033.

Survival Horror Integration: The gas mask is more than a filter timer; it’s a visceral interface. Filters last 3-5 minutes (displayed on the wristwatch). The mask gets splattered with mud, blood, and water, requiring a manual wipe. Condensation builds as the filter ages, clouding vision. This constant upkeep makes surface sections—swampy, irradiated, and bathed in an oppressiveDAY-NIGHT CYCLE—feel genuinely hazardous. Ranger Mode removes the HUD entirely. Ammunition must be counted manually by checking the weapon model, filter times on the watch, and item selection by audio cues alone. This is not just “hard”; it is a deliberate return to simulationist tension.

Combat & Mutants: Combat is weighty and lethal. Human enemies use cover effectively, and headshots are decisive. Mutants are more varied and terrifying: the swarming Nosalises, the armored Shrimps (with vulnerable bellies), the web-weaving Spiderbugs (weakened by light), and the legendary “Big Mama” bear. Boss fights often require puzzle-like observation (attack the bear’s back when it charges, target the weak red wheels of the armored rail tank). The “Flame-thrower Mini-Boss” at the Theatre and the final armored train assault are memorable set-pieces that force adaptation.

Flaws & Innovations: The AI’s pathfinding and “guard must be crazy” Moments (investigating noises but not missing comrades) remain a weak point. “Invisible walls” and inaccessible paths contradict the game’s otherwise explorative nature. However, the philosophy of minimal HUD is the game’s greatest innovation. By forcing reliance on audio cues (enemy footsteps, the click of picking up items), visual tells (the watch, the gas mask’s state), and diegetic information (Artyom’s journal read by lighter), it achieves an unparalleled level of immersion. The game feels like a lived-in struggle, not a score-chasing arcade.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Eternal Echo of Moscow

The Moscow Metro is not just a setting; it is the game’s soul. 4A’s 4A Engine renders the tunnels with a claustrophobic, diesel-punk grandeur. The art direction is a masterclass in environmental storytelling. Each station is a distinct micro-culture: the burlesque of Theater, the bloody class war murals of Red Line stations, the pristine, authoritarian order of Reich stations, the chaotic bazaar of Venice. Details are everywhere—scratched slogans, personal belongings left on beds, propaganda posters, and the omnipresent, dog-eared copies of Glukhovsky’s Metro 2033 novel.

The surface sections are where the game’s vision achieves transcendence. Abandoned Dead City is a masterpiece of ghostly horror, where nuclear shadows (“Living Shadows”) flicker at the edge of vision, audible only as whispers that cease when you look. The swampy, overgrown landscapes of later levels (Garden, Bridge) are a brutal departure from the frozen wastes of 2033. The melted snow has created a miasma of water, toxic plants, and new mutants. The oppressive, pea-soup fog and sudden, blinding rainstorms make navigation treacherous. This is a world actively decaying and reclaiming itself.

Sound design is arguably the game’s greatest achievement. It is a symphony of dread. The constant, raspy breathing through the gas mask, the hiss-click of Spiderbug mandibles, the distant roar of Mama Bear, the unsettlingly human-like whispers of ghosts—all are spatially accurate, forcing the player to turn their head. The soundtrack by Alexei Omelchuk is a sparse, melancholic blend of ambient drones, religious chants, and tense percussion that never overwhelms the diegetic sounds. Gunfire is concussively loud, making stealth not just a tactical choice but a survival necessity. The audio cues for gameplay (the distinctive shink of a throwing knife, the clack of a metal bearing for the Tikhar) are seamlessly woven into the soundscape.

Together, world, art, and sound create a believable, tactile reality. You don’t just see the grime on the walls; you feel the dampness. You don’t just hear a mutant; you hear it through the concrete of a ventilation shaft. This is environmental narrative at its peak, where the level design itself tells the story of survival, factionalism, and the haunting persistence of the past.

Reception & Legacy: A Contested Classic

At launch, Metro: Last Light received generally favorable reviews, with a Metacritic score of 82/100 on PC. Critics were nearly unanimous in their praise for its atmosphere, world-building, and tone. GameSpot‘s 9/10 review called it a “survival horror shooter of the highest order,” lauding how “resource management… makes you feel threatened by the state of the world.” Polygon (8.5/10) highlighted its “real sympathy” for characters. Game Informer (8.75/10) praised its “tense, satisfying” combat.

The criticisms were equally consistent. The AI was frequently cited as unrefined—enemies had inconsistent perception and reaction times. The monster designs (particularly the Watchmen) were called derivative (“a poor man’s Doom“). The final boss and certain linear sequences were frustrating. Technical issues, especially on Windows at launch, marred the experience for some. The Ranger Mode controversy was a major talking point; many saw locking the “definitive” experience behind a pre-order as a cynical exploitation of the hardcore audience. Deep Silver defended it as a response to retailer demands for exclusive content.

Commercially, it was a watershed. It was the best-selling retail game in the UK upon release and, crucially, its first-week US sales surpassed the lifetime retail sales of Metro 2033. This validated Deep Silver’s investment and proved the niche appeal of hardcore, single-player focused shooters. The Limited Edition and subsequent DLC (Faction Pack, Tower Pack, Developer Pack, Chronicles Pack) extended its lifecycle and added substantial content, including the mission where you play as Anna, Pavel, and Ulman.

The 2014 Metro Redux compilation, bundling the remastered 2033 and Last Light for PS4/Xbox One/PC, was a critical and commercial success, selling over 1.5 million copies. It served as the definitive entry point for a new generation and highlighted the timelessness of the Metro aesthetic. The Nintendo Switch port (2020) further proved the game’s adaptability and enduring appeal.

Legacy and Influence:

Metro: Last Light stands as a touchstone for “immersive sim-lite” FPS design. Its emphasis on systemic tension (scarcity, sound, light), environmental storytelling, and morality-by-choice rather than dialogue wheels influenced a generation of narrative shooters. It demonstrated that a single-player, story-driven experience could be both a critical darling and a commercial success in an era increasingly dominated by multiplayer and live-service models. The Ranger Mode precedent, while controversial, highlighted a demand for unadulterated, challenging experiences, paving the way for later “classic” or “hardcore” modes in other franchises.

The game’s success directly enabled its glorious successor, Metro Exodus (2019), which expanded the vision to a vast, open-ended landscape while retaining the core philosophy. More broadly, Metro: Last Light is a testament to artistic vision triumphing over adversity. Forged in the difficult final days of THQ by a studio working in freezing conditions, it delivered a uniquely Eastern European, deeply philosophical take on the apocalypse—one where the central conflict is not over resources, but over the very soul of humanity. It is a game that respects its players’ intelligence, challenges their reflexes, and lingers in their minds long after the final shot is fired.

Conclusion: An Imperfect Beacon

Metro: Last Light (Limited Edition) is not a flawless game. Its AI stumbles, its monster designs occasionally miss the mark, and its linearity can feel restrictive. The controversy around Ranger Mode remains a stain on its launch, a necessary evil born of an industry transitioning to pre-order culture. Yet, these flaws are the cracks in a formidable edifice. Its strengths are so monumental—the bone-deep atmosphere, the devastatingly human story, the revolutionary (if troublesome) HUD-less design, the unforgettable world—that they dwarf its weaknesses.

As a historical artifact, it represents a culmination of a specific design philosophy: the immersive, systemic, story-first shooter. As a narrative, it is a profound meditation on guilt, redemption, and the fragile hope that even the most monstrous acts might be forgiven. As a gameplay experience, it is a relentless, resource-intensive trial that rewards patience, observation, and moral consideration over twitch reflexes.

In the Metro series, Last Light is the crucial bridge. It takes the raw, atmospheric promise of 2033 and refines it into a coherent, deeply satisfying whole. It is the game that proved the franchise’s staying power and set the stage for the epic scale of Exodus. For those willing to brave its irradiated swamps and claustrophobic tunnels, Metro: Last Light offers a journey unlike any other in the medium—a bleak, beautiful, and ultimately hopeful testament to the idea that even in the deepest dark, a single, flickering light can guide the way home. It is, without question, one of the most important and exceptional first-person shooters of the 2010s.