- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: S.A.D. Software Vertriebs- und Produktions GmbH

- Genre: Compilation

Description

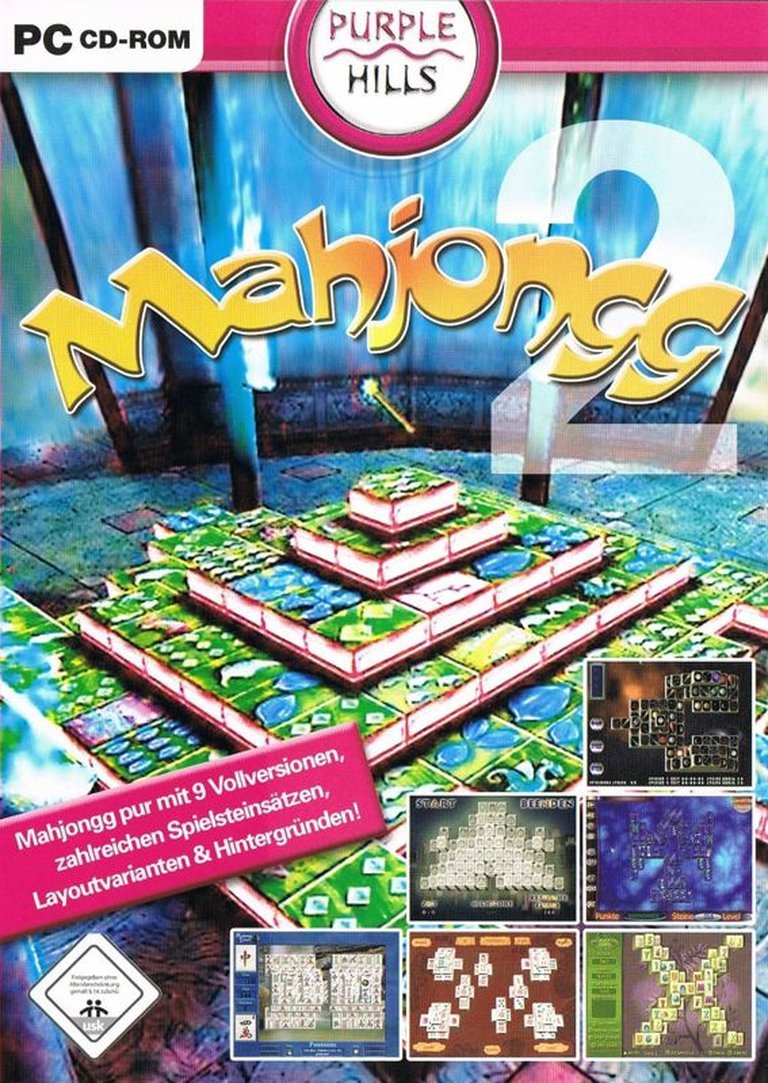

Mahjongg 2 is a retail compilation released in October 2004 for Windows, bundling a diverse array of Mahjong solitaire games including 3DJongg, Amazing Mahjongg 3D, and other variants, alongside 15 shareware titles, all centered around tile-matching puzzle gameplay with various themes and implementations.

Where to Buy Mahjongg 2

PC

Mahjongg 2: A Digital Anthology at the Crossroads of Tradition and Casual Gaming

1. Introduction: The Title That Wasn’t—A Compilation as Cultural Artifact

To speak of Mahjongg 2 is not to speak of a single, cohesive creative vision, but of a commercial artifact frozen at a specific moment in the digital translation of an ancient pastime. Released in October 2004 for Windows by the German publisher S.A.D. Software Vertriebs- und Produktions GmbH, Mahjongg 2 is not a sequel in the narrative or mechanical sense. Instead, it is a budget-priced retail compilation—a time capsule of the early-2000s casual PC gaming landscape, where the tiles of Mahjong Solitaire (a genre distinct from the four-player Mahjong) were being repackaged with relentless fervor. Its thesis is not one of innovation, but of aggregation and accessibility. This review posits that Mahjongg 2’s historical significance lies not in its gameplay—a well-worn formula—but in its role as a mass-market vessel, bridging the gap between the deep, social tradition of Mahjong and the solitary, click-driven digital casual games that would dominate the coming decade. It is a monument to quantity over quality, a bundle that reflects a period when “Mahjong” in the West was almost universally synonymous with tile-matching solitaire, a semantic drift from its roots that this compilation both exploits and reinforces.

2. Development History & Context: The Assembly Line of Pixels and Tiles

The development history of Mahjongg 2 is, by necessity, the history of its parts—a collection of disparate projects bundled under one SKU. The game was published by S.A.D. Software, a German company operating in the competitive European budget and “shareware” software market. The early 2000s saw a proliferation of small studios and independent developers creating Mahjong Solitaire variants, often as portfolio pieces or to sell via the burgeoning shareware model (try-before-you-buy, typically $15-$20 for a registered version).

-

The Studio & Vision: There is no evidence of a singular “S.A.D.” development team. Instead, S.A.D. acted as an aggregator and distributor. Their “vision” was commercial: to create a package with perceived high value by including numerous variants. The compilation lists eight primary titles: 3DJongg, Amazing Mahjongg 3D, JongiJongo 2, Mahjongg, Mahjongg Deluxe, Mahjongger, MD-Mahjongg, Twilight Mahjongg, MegaMahjongg. Many of these were likely existing shareware titles from different developers, rebranded or slightly modified for inclusion. The lead developer credits are unobtainable from public sources, underscoring the anonymous, production-line nature of the project.

-

Technological Constraints & Landscape: The game was built for Windows (likely targeting Windows 98/ME/2000/XP) and distributed on CD-ROM. This places it at the tail end of the physical media era for casual games. Technologically, it represents the standard of its time: DirectX-based 2D or basic 3D (for titles like Amazing Mahjongg 3D) graphics, MIDI or low-bitrate digital audio, and simple point-and-click interfaces. The constraints were not hardware—even low-end PCs could handle tile rendering—but design and content. The challenge was differentiation. How do you make your Mahjong Solitaire game stand out? The answer in Mahjongg 2 was through thematic reskins (e.g., Twilight with a darker aesthetic, 3DJongg with a rotating board) and layout variety.

-

Gaming Context—The Solitaire Tsunami: The year 2004 was peak “casual games” before the term was fully co-opted by social/mobile. Microsoft’s Microsoft Plus! Pack for Windows XP (2003) had included Mahjong Titans, introducing millions to the genre. The runaway success of PopCap’s Bejeweled (2001) had proven the addictive power of simple, match-based mechanics. Mahjongg 2 arrived as part of a flood: retail shelves were lined with compilations like Puzzle Inlay, 7 Games of the World, and countless “Super Mahjong” collections. It was a low-cost, low-risk product for publishers, capitalizing on the established appeal of the tile-matching format and the perceived cultural cachet of “Mahjong.”

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Absence of Story

It is here that the review must confront a fundamental truth: The included games in Mahjongg 2 have no narrative, characters, dialogue, or thematic depth in any literary sense. They are pure abstract puzzles. The “theme” is purely aesthetic and atmospheric.

- Plot: None. The “story” is the player’s own progression through a series of increasingly complex tile layouts.

- Characters: None. The player is an disembodied cursor. There is no protagonist, no adversary (the game is solo), no NPCs.

- Dialogue: None. The only “text” is score tallies, timer displays, and perhaps title screen logos.

- Underlying Themes: The themes are those of contemplation, pattern recognition, and closure. The core experience is Zen-like: the clatter of virtual tiles, the slow revelation of the board, the tension of being blocked, the satisfying cascade of a successful clear. Some variants, like Twilight Mahjongg, might use a dusk-inspired color palette to evoke a mood of quiet solitude. Amazing Mahjongg 3D uses perspective to create a sense of spatial puzzle-solving. But these are shallow, surface-level associations. The compilation does not engage with the rich history, gambling culture, or social ritual of actual four-player Mahjong—the themes meticulously documented in sources like the Sloperama timeline or the Oh My Mahjong blog. It presents Mahjong as a visual motif and a puzzle mechanic, stripped of all cultural and historical weight. This is not a failure of Mahjongg 2 specifically, but a defining characteristic of the entire “Mahjong Solitaire” genre it represents.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Engine of Endless Tiles

The value of Mahjongg 2 is entirely a function of the sum of its parts, each implementing the core Mahjong Solitaire (also called “Shanghai Solitaire” or “Tile Matching”) ruleset with minor permutations.

-

Core Gameplay Loop: A pyramid or other ornate layout of stacked tiles (typically 144 standard Mahjong tiles: 3 suits * 9 ranks * 4 copies + 4 winds + 3 dragons + 8 bonus tiles). The player clicks two uncovered, unblocked (not covered on any side except the bottom, and not blocked on the left or right by adjacent tiles) identical tiles to remove them. The goal is to clear the entire board. Strategic depth comes from tile removal order; a wrong move can block crucial tiles.

-

Combat/Progression: There is no combat. Progression is through levels. Each “game” or “layout” is a level. Completion unlocks the next, typically in a preset sequence. Some variants might have a career mode or a map of screens to select from. The only “adversary” is the board itself and, in some versions, a ticking clock.

-

Character Progression & Systems: None. There are no avatars, experience points, or skill trees. Any “progression” is the player’s own skill improvement at pattern recognition and board management.

-

UI & Innovative/Flawed Systems:

- UI: Standard for the era. A main menu to select a game variant and a specific layout. In-game: a large central board, a timer (often optional), a score display, and buttons for “Hint” (highlights a pair, usually with a point penalty), “Undo” (limited uses), and “Shuffle” (re-randomizes remaining tiles, often with a limit or penalty).

- Innovation (within the bundle): The value is in variety. 3DJongg and Amazing Mahjongg 3D introduce a 3D rotating board, adding a spatial reasoning layer where you must rotate the view to access tiles. MegaMahjongg likely offers a larger tile count or more complex layouts. Twilight Mahjongg may have a thematic visual filter. The inclusion of 15 shareware variants suggests even more stylistic and layout diversity.

- Flaws (Systemic to the Genre & Bundle):

- The Solvability Problem: A major flaw in many pre-generated layouts is unwinnability. Without a sophisticated algorithm to guarantee a solution (a complex problem for arbitrary layouts), players can waste time on impossible boards. Some versions may have a “shuffle” feature to mitigate this, but it’s a band-aid.

- Replay Value: Once all layouts in a variant are solved, the game is “beaten.” The bundle’s value is in the sheer number of layouts across 9 variants, but the core mechanics do not change.

- Lack of Modern Features: No online leaderboards (a staple even in 2004, e.g., on MSN Games), no persistent profiles, no daily challenges. It is a purely offline, single-player experience.

- The “Shareware” Gap: The inclusion of 15 shareware variants is a double-edged sword. It adds bulk but means 15 games are locked behind a “register to unlock all levels” prompt, diminishing the perceived completeness of the purchase.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetic of the Digital Tea House

The “world” of Mahjongg 2 is the player’s desktop. The atmosphere is entirely constructed by the visual and audio presentation of each variant, which ranges from functional to mildly immersive.

-

Setting & Atmosphere: There is no diegetic setting. The “world” is the tile layout itself. The atmosphere depends on the chosen variant:

- Mahjongg / Mahjongg Deluxe: Likely the “classic” aesthetic—wood-grain backgrounds, traditional bamboo and bone tile textures, subtle Asian-inspired background music (often generic “Oriental” synth melodies common in the era).

- 3DJongg / Amazing Mahjongg 3D: A more “modern” or “tech” feel, possibly with a rotating, starfield or gradient background, metallic tile sheens.

- Twilight Mahjongg: As the name suggests, a dusk/evening palette—deep blues, purples, soft glows—attempting a serene, contemplative mood.

- JongiJongo 2 / MD-Mahjongg: Possibly more cartoonish or stylized, targeting a younger or more casual audience.

-

Visual Direction: It is a product of its time. Tile designs range from decently authentic (attempting to replicate traditional Chinese character tiles for the suited tiles, with wind and dragon symbols) to simplified and symbolic (using numbers/letters for suits in some shareware variants). The art is generally semi-realistic 2D sprites, with the 3D titles using simple polygon models with texture mapping. Animation is minimal: tiles appear with a slight drop-in effect, removed tiles fade or sink. There is no fluid physics or advanced particle effects. The visual direction aims for a balance between cultural recognition (the familiar Mahjong tile shapes) and digital clarity (tiles must be easily distinguishable at a glance).

-

Sound Design: The audio palette is narrow but functional.

- Tile Sounds: A consistent, satisfying click-clack or tap when selecting tiles. A deeper thud or chime upon removal. These sounds are the primary auditory feedback and are crucial to the tactile illusion.

- Ambient Music: Looping MIDI tracks, typically in the “Asian Fusion” or “New Age” genres popular in early-2000s PC games—pentatonic scales, gentle flutes or shakuhachi, soft percussion. It is meant to be unobtrusive, meditative, but often devolves into repetitive, tinny MIDI.

- UI Sounds: Clicks for buttons, a buzzer for invalid moves.

- Contribution to Experience: The sound design’s goal is immersion through consistency and mild exoticism. The tile sounds provide rhythmic, satisfying feedback that mimics the physical game. The music attempts to place the player in a “calm, Eastern” headspace, though it often feels like a generic pastiche. It serves the purpose of filling silence and reinforcing the game’s categorization as a “relaxing puzzle,” but lacks the artistry of a dedicated soundtrack.

6. Reception & Legacy: The Silent Success of the Assembly

-

Contemporary Reception: Mahjongg 2 itself was almost certainly not reviewed by major critics. It was a low-budget, shelf-warmer title in a saturated market. Its “reception” was purely commercial and demographic: it sold to casual players, particularly older adults and the “solitaire crowd” who frequents outlets like Big Lots or software sections of department stores. The absence of critic reviews on MobyGames and the “Be the first to review” message on its pages are definitive. The value proposition was clear: “9 games in one!” for a low price. The quality of the individual titles was secondary to the feeling of getting a lot.

-

Evolution of Reputation: The game has no reputation to evolve. It exists in a state of archival obscurity, known only to completionists, retro PC game collectors, and those who may have purchased it on a whim in 2004. It is the definition of a forgettable product. Its legacy is not as a title, but as a data point.

-

Influence on the Industry & Subsequent Games: Mahjongg 2 was not influential. It did not pioneer mechanics, set trends, or attract a community. Instead, it is a perfect example of the “budget compilation” model that thrived in the early 2000s PC market. This model influenced:

- The Value Packaging Strategy: The idea of bundling multiple thematic variants of a core puzzle (e.g., Jewish Mah Jongg, Christmas Mah Jongg, Ocean Mah Jongg) to extend playtime and justify a retail price.

- The “Casual Suite” Concept: It predated the more polished “casual game suites” from publishers like PlayFirst or PopCap, but shared the same philosophy: one core mechanic, many skins and layouts.

- The Digital Translation of Tradition: It participates in the broader, significant trend of digitizing traditional games. However, while sources like the Sloperama timeline and Oh My Mahjong blog detail the centuries-long evolution of four-player Mahjong—its rules wars, cultural significance in Jewish-American communities, and rise as a mind sport—Mahjongg 2 and its ilk created a parallel universe where “Mahjong” meant solitary tile-matching. This had the profound effect of decoupling the game from its cultural and social history for a generation of Western players. The influence is in the popularization of a simplified, ahistorical avatar of the game.

-

Place in Video Game History: Its place is marginal. It is a footnote in the history of casual PC gaming and a perfect specimen of the early-2000s compilation genre. It represents the moment before the market consolidated around a few polished franchises (like Puzzle Quest or later, mobile titles) and the era of dozens of indistinguishable clones. Its historical value is anthropological: it shows what “Mahjong” looked like to the average Western PC user in 2004—a colorful, solitary time-passer, utterly disconnected from the complex, social, competitively serious game described in academic citations (over 1,000 according to MobyGames) and the efforts of organizations like the National Mah Jongg League (founded 1937) or the World Mahjong Organization.

7. Conclusion: A Verdict of Context, Not Quality

Final Verdict: Mahjongg 2 is not a “good” or “bad” game in any meaningful critical sense. It is a functional artifact. As a Mahjong Solitaire experience, it delivers what it promises: dozens of hours of tile-matching across various visual themes. The mechanics are sound, if unoriginal. The presentation is dated but serviceable.

Its true evaluation must be historical and cultural. As a digital object, it is a snapshot of a transitional moment—the last gasp of the CD-ROM compilation era for casual games, and the zenith of the “Mahjong Solitaire” as a generic Windows time-waster, stripped of the rich tapestry of its namesake. It captures the moment when the word “Mahjong” in the West became permanently associated with a single-player puzzle, a semantic shift that pioneers like Joseph Babcock (with his 1920 “Red Book”) could never have anticipated.

For the game historian, Mahjongg 2 is invaluable as a primary source. It demonstrates marketing strategies, technical limitations, and aesthetic trends of its time. For the player, it is a curiosity—a time capsule of a quieter, pre-mobile, pre-Freemium era of digital puzzling, where content was measured in megabytes on a disc, not downloads or in-app purchases. It is a testament to the fact that the most profound impact a game can have is not through its own brilliance, but by being a vector for a name, a concept, a misconception that shapes public understanding for decades. Mahjongg 2 did not just sell tile-matching puzzles; it sold the very idea of what “Mahjong” is to a casual audience, an idea that persists, powerfully and inaccurately, to this day. In that, it is more historically significant than any single, polished Mahjong Solitaire game could ever be.