- Release Year: 2011

- Platforms: Windows

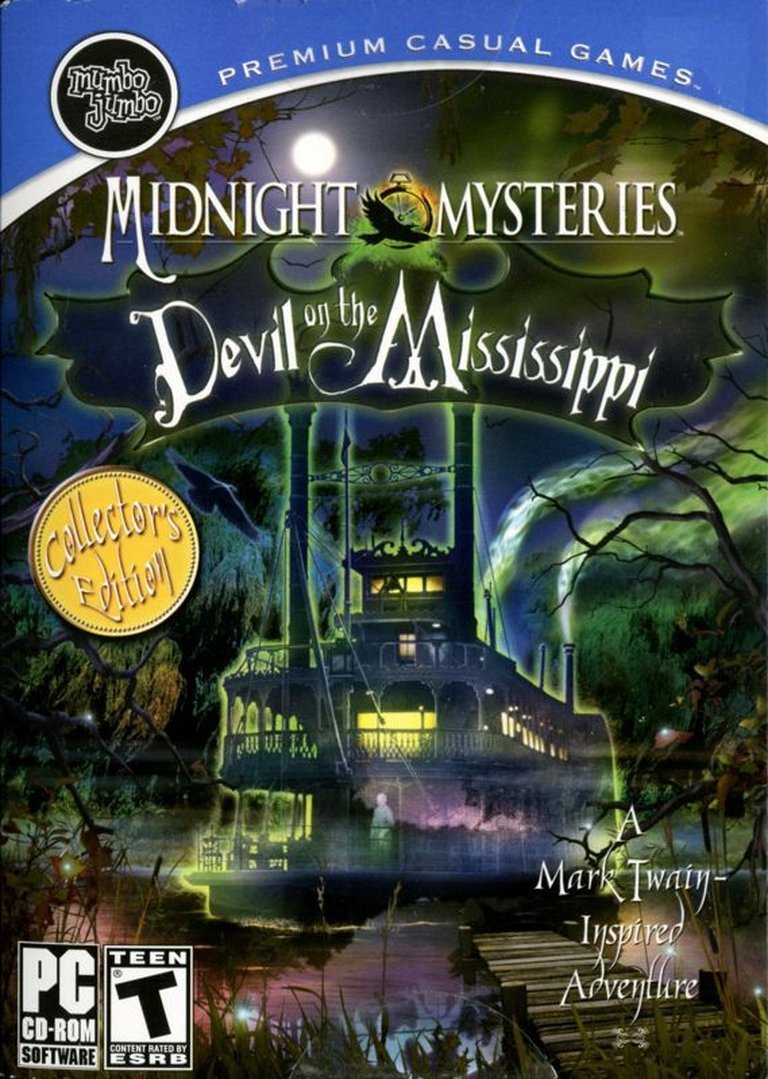

- Publisher: MumboJumbo, LLC

- Developer: MumboJumbo, LLC

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Puzzle elements

Description

Midnight Mysteries: Devil on the Mississippi is a hidden object adventure game where players investigate supernatural occurrences and solve paranormal puzzles along the iconic Mississippi River. As part of the celebrated Midnight Mysteries series, this Collector’s Edition blends detective mystery with horror elements, challenging players to uncover a devilish conspiracy in a first-person perspective filled with intricate puzzles and atmospheric storytelling.

Gameplay Videos

Midnight Mysteries: Devil on the Mississippi (Collector’s Edition) Guides & Walkthroughs

Midnight Mysteries: Devil on the Mississippi (Collector’s Edition): A Spectral Steamboat Ride Through Literary History

Introduction

In the bustling ecosystem of early 2010s casual gaming, few subgenres were as reliably profitable or as critically dismissed as the hidden object puzzle adventure. Within this crowded field, MumboJumbo’s Midnight Mysteries series carved out a distinct niche, blending historical figures, Gothic horror, and intricate puzzle design. Devil on the Mississippi, its 2011 Collector’s Edition, represents a high-water mark for the franchise—a title that leverages its pulp-inspired premise not just as a veneer, but as the fundamental engine for its narrative and mechanical identity. This review argues that while the game is a product of its time and genre, its sophisticated interweaving of American literary iconography with Elizabethan conspiracy, coupled with mechanically varied and often clever puzzle design, elevates it beyond mere time-filler into a meticulously crafted piece of interactive ghost storytelling. It is a game that understands its audience’s desire for both atmospheric immersion and intellectual gratification, delivering a experience that remains impressively cohesive over its dozen-hour journey.

Development History & Context

Studio & Vision: MumboJumbo, LLC, the developer and publisher, was a perennial force in the casual games market throughout the 2000s and 2010s. Renowned for flagship series like Luxor and 7 Wonders, they possessed a formidable internal engine for creating polished, accessible, and visually appealing games for the “Big Fish Games” and “iWin” distribution model. The Midnight Mysteries series, which began with The Edgar Allan Poe Conspiracy in 2009, was their dedicated foray into narrative-driven hidden object adventures. Devil on the Mississippi (2011) was the third main entry, following Salem Witch Trials (2010). The studio’s vision was clear: to create games with “movie-like special action scenes” (as one user review noted) that transcended the static, illustrated backdrops common to the genre, aiming for a more dynamic, story-centric experience.

Technological & Market Context: Released in 2011, the game targeted the Windows PC casual market, also appearing on Macintosh and later iPad. Technologically, it utilized pre-rendered 2D art with animated elements and simple 3D effects (like the ghostly riverboat’s appearance), a cost-effective standard for the era that allowed for rich, painterly visuals without the complexity of full 3D environments. The business model was firmly “premium casual”: sold as a complete download or physical CD-ROM (as seen in Walmart and eBay listings) with a Collector’s Edition premium, a direct response to competitor formats like Mystery Case Files which popularized the CE model with bonus content. The gaming landscape was one where hidden object games (HOGs) had matured beyond simple lists; players expected integrated puzzles, character interactions, and a narrative that justified the object-finding. Devil on the Mississippi arrived as this evolution was peaking, competing directly with titans like Big Fish’s own Mystery Case Files and Phantom’s series.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The game’s plot is a delightful historical mashup, premised on a supernatural consequence of a real-world literary debate. The narrative hook is potent: Mark Twain’s ghost directly petitions the player for help, stating an “evil that has been stalking him in the afterlife.” The catalyst is Twain’s own ruminative passion for the Shakespeare authorship question—the controversial theory that someone other than William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote theplays. In the game’s logic, this academic questioning is not an idle act; it is a supernatural key that awakens a malevolent force tied to the true author’s secret.

This premise allows for a breathtaking chronological and geographical hopscotch:

1. Hannibal, Missouri (circa 1880s): The starting point, steeped in Twain’s own boyhood haunts from The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. The player interacts with ghostly locals like Tom Sawyer himself and “Joe,” a skeletal figure from Clemens’ past, to repair a fence, board a steamboat, and retrieve crucial artifacts. The atmosphere is one of muddy, nostalgic Americana, already undercut by spectral intrusion.

2. Elizabethan London (1600) & Stratford-upon-Avon: The course shifts dramatically to the gritty, superstitious world of the Globe Theatre, the Tower of London, and Shakespeare’s home. Here, the player must interact with a witch (a clear nod to the supernatural fears of the era), the Bard himself, and the spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham. The core objective is to prove Shakespeare’s legitimacy by opening his tomb, a quest that involves alchemy (acid to dissolve bars), political intrigue (obtaining a permission letter), and puzzle-solving born of Elizabethan symbology.

3. Connecticut (1880s): The journey moves to the Clemens family home, a site of personal tragedy and financial ruin (the “Bankruptcy Doc”). This chapter is deeply personal, focusing on Twain’s wife, Livy (“Livy Clemens”), his children, and his business failures. The introduction of Nikola Tesla as a supporting ghost is a masterstroke of anachronistic historical fiction, tying Twain’s later life to the electrical age and providing a sci-fi counterpoint to the Elizabethan occult.

4. Deptford, England (1593): A darker, seedier pre-Elizabethan London, involving a tavern confrontation, a graveyard excavation with the accused murderer John Perry, and a literal cannon blockade puzzle on the docks—a brilliant mechanical set-piece that feels ripped from a pirate adventure.

5. Chiselhurst, England & The Final Crypt: The climax returns to Walsingham’s tomb, transforming it into a labyrinthine puzzle-box. The gear-alignment puzzle and the subsequent “bone collection” ritual to lay a restless spirit (Marlow) to peace form the game’s apocalyptic stakes.

Themes: The narrative weaves several compelling threads:

* Literary Legacy vs. Historical Truth: The game treats authorship as a sacred, almost magical contract. Proving Shakespeare wrote his works is framed as a necessary act to seal away a “devil.” Twain’s guilt and obsession are painted as a tragic, far-reaching error.

* Redemption & Closure: Both Twain and the Elizabethan ghosts (the witch, Perry, Marlow) seek resolution. The player acts as a psychopomp, guiding spirits to peace by correcting historical wrongs or facilitating understanding.

* The Tangibility of History: Objects are the currency of history. A manuscript, a signet ring, a family painting, a bankruptcy document—each hidden object is a tangible piece of a narrative that, when assembled, reconstructs a suppressed truth. The inventory system isn’t just a mechanic; it’s the player’s scrapbook of historical reparation.

Dialogue & Character: The dialogue is functional, delivering plot and puzzle clues efficiently. It avoids excessive “read-the-entire-screen” blocks, a point praised by users. Twain is portrayed as witty, guilt-ridden, and determined. His dynamic with the more stoic or tormented historical ghosts creates a compelling contrast. The Elizabethan characters, though less fleshed out, are effective archetypes: the persecuted witch, the paranoid spymaster, the guilty murderer. Theintegrated strategy guide (a CE feature) often appears in-game as Twain or another character offering cryptic advice, blurring the line between help and diegesis.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Devil on the Mississippi exemplifies the “advanced” HOG design of its era, where object-finding is the primary verb but is embedded in a web of other interactions.

Core Loop: The player navigates a series of static (but often animated) scenes. Each location has a clear objective (“Restore the fence,” “Find the Pilot’s License”), which is broken down by the Goals tab—a crucial UI innovation that keeps the player oriented without constant hint use. Play is largely task-driven and linear, but with occasional branches (e.g., exploring different rooms on the steamboat before proceeding).

Hidden Object Scenes: These are the bread and butter. They come in two forms:

1. Standard Lists: Find 10-15 named items against a detailed, cluttered background. Items are often cleverly integrated into the scene’s theme (e.g., “Sailor’s Tool” on a ship).

2. Puzzle Clues: Some items are described vaguely (“Small Writing Instrument,” “Green Gem”), requiring lateral thinking. More importantly, completing a list often yields a critical inventory item or clue for the journal.

Inventory & Combination System: The game features a robust, scrollable inventory. The true puzzle depth emerges from combining items (e.g., Dull Knife + Whetstone = Sharp Knife). These combinations are often intuitive but context-specific, encouraging experimentation. The system is praised in user reviews for its logical clarity.

Minigames & Puzzles: This is where the game shines. It avoids repetitive HOG fatigue by interspersing a wide variety of self-contained puzzles:

* Sliding Tiles: Floor tile puzzle in the Connecticut house.

* Gear Alignment: Matching colored gears in Walsingham’s tomb.

* Pattern-Matching: Skull lock in Deptford, card-suit lock in the bonus chapter.

* Logic Grids: The “Numbered Blocks” puzzle in the Globe Theatre, requiring placement to form mini-squares containing numbers 1-8.

* Physics-Based: The steamboat boiler puzzle (stacking coal) and the cannonball “Battleship” puzzle in Deptford.

* Hidden Integrated: The pool table “break” puzzle, where aiming the shot clears the table and reveals a document.

* Exploration Mazes: Dragging a lantern through maze-like lofts in the Globe Theatre.

* Item Placement: Restoring the church in Chiselhurst by placing artifacts, or the dollhouse puzzle in the playroom.

The puzzles are generally well-sequenced in difficulty, with the “Numbered Blocks” and “Coin Pattern” puzzles standing out as particularly elegant and thematic.

Collectibles & Penalties:

* Clovers: Hidden green four-leaf clovers scattered everywhere. Collecting all 100 unlocks the “Unlimited Hidden Objects” mode.

* Ravens: Red ravens that increase the number of available hints. A clever penalty exists: rapid clicking causes a black cat to jump out and briefly freeze the cursor, discouraging mindless clicking.

* Dem Bones: The CE-exclusive bonus game is a meta-hunt for 80 skeletal bones across all main game locations, with a specific distribution (e.g., “Tesla’s Lab – 9”).

UI & Accessibility: The interface is clean. The Journal auto-updates with key plot points. The Hint system is generous; ravens expand it, and it can show the next action or highlight a hidden object. The integrated strategy guide is a major CE selling point, though purists might avoid it. One user noted the “Goals tab” could sometimes be vague, a minor flaw in an otherwise intuitive system.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Art Direction & Visuals: This is the game’s most universally praised aspect. User reviews repeatedly use terms like “fantastic artwork,” “beautiful graphics,” and “movie-like special action scenes.” The art style is detailed, slightly saturated, and leans into a gothic-romantic aesthetic. Key locations are vividly realized:

* The ghostly Mississippi riverboat is a constant, eerie presence, its appearance a memorable “spectacle” moment.

* Elizabethan London is all timber-framed buildings, fog, and candlelit interiors.

* The Clemens mansion in Connecticut is a warm but haunted domestic space, filled with period detail.

The “Concept Art” gallery in the CE lets players appreciate the background designs, character sketches, and promotional art, revealing a thoughtful design process.

Atmosphere & Sound: The game builds a consistent, chilling mood. Ambient river sounds, creaking wood, and period-appropriate music (orchestral with a mystical bent) underscore every scene. Sound design is used for punctuating puzzle solutions, ghost appearances, and jumpscares (like a sudden crash). The voice acting, while limited to key interactions, is competent and fits the serious tone. The “Panic Room” (referenced in the CE description on iWin) likely highlights these special effects and sound moments, suggesting the developers were proud of their cinematic ambitions.

The world-building successfully marries two distinct historical periods. The transition from the muddy, expansive Mississippi to the cramped, conspiratorial streets of London is jarring in the best way, reinforcing the game’s central theme: Twain’s 19th-century curiosity has violently unearthed a 16th-century secret. Nikola Tesla’s lab, with its coils and crackling electricity, serves as a fascinating bridge between these eras.

Reception & Legacy

Critical & Commercial Reception: Formal critic reviews are scarce on MobyGames (n/a score, only one user rating), but player reception from the aggregated sources is overwhelmingly positive. The average user score on MobyGames is 4.4/5. Reviews on iWin and PCMacstore are effusive:

* Praised for its storyline (“pulled me into the story,” “excellent storyline”).

* Lauded for graphics and effects (“incredible graphics and special effects”).

* Valued for content and replayability (“lasted me several hours,” “excellent replay value”).

* Noted for being accessible yet deep—one parent highlighted its appeal to a 4-year-old with parental help, while another adult found it “intense.”

Commercially, its presence on mainstream retail sites like Walmart (as a physical CD-ROM) and frequent listings on eBay (at used prices as low as $1-$7) indicates solid, if not spectacular, sales for the casual market. It was a product that moved through the discount bin, a common lifecycle for HOGs.

Legacy within the Series & Genre: Devil on the Mississippi is the second entry in the Midnight Mysteries series (after Salem Witch Trials) and was followed by Haunted Houdini (2012). It cemented the series’ formula: a famous historical figure in peril, a supernatural threat rooted in a historical mystery, globe-hopping locations, and a CE package stuffed with bonuses. Its influence is more about solidifying conventions than breaking new ground. It demonstrated that a HOG could sustain a complex, multi-location narrative with a consistent thematic through-line (literary conspiracy). The puzzle variety set a benchmark; later titles in the series and competitors would feel pressure to match its mechanical diversity.

In the broader history of casual adventure games, it represents the mature phase of the “Big Fish” HOG model. It perfected the balance of hidden object busywork with genuine puzzle-solving and a narrative that, while pulp, had intellectual pretensions. Its legacy is as a paragon of its subgenre—a game that delivered exactly what its target audience wanted with exceptional polish, even if it never broke into the mainstream gaming consciousness.

Conclusion

Midnight Mysteries: Devil on the Mississippi (Collector’s Edition) is not a hidden gem—it was a known, successful commodity in its time. Its historical significance lies in its exemplary craftsmanship within a marginalized genre. It is a game that commits entirely to its peculiar premise: the idea that a debate about Shakespeare’s identity could summon a demon and require the logistical aid of a spectral Mark Twain and Nikola Tesla. The narrative, while nonsense by academic standards, is a clever framework that justifies its whirlwind tour of iconic settings. Mechanically, it offers a staggering variety of puzzles that are more often clever than frustrating, integrated seamlessly into the object-hunt core.

Its weaknesses are those of its era: the linear progression can feel like a checklist, the voice acting is sparse, and the hidden object scenes, while beautiful, rely on a visual language of clutter. Yet, for the patient player willing to absorb its atmospheric world and engage with its puzzle-box logic, it offers a deeply satisfying experience. It is a game that respects the player’s intelligence, expecting them to connect clues across chapters and centuries.

In the grand canon, it will not be mentioned alongside Myst or Grim Fandango. But within the specific lineage of the casual adventure—the games played on laptop bedsides and during afternoon breaks—it stands as a masterclass in genre execution. It is a testament to MumboJumbo’s understanding that a great hidden object game needs more than a long list of items; it needs a haunting premise, a memorable cast of ghostly guides, and puzzles that feel like they belong to the story. Devil on the Mississippi delivers on all fronts, securing its place as a beloved and mechanically robust entry in a significant, if often overlooked, chapter of game history. For scholars of casual game design, it is a essential case study; for players seeking a spooky, literary, and intellectually engaging hidden object adventure, it remains a highly recommended voyage.