- Release Year: 2016

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

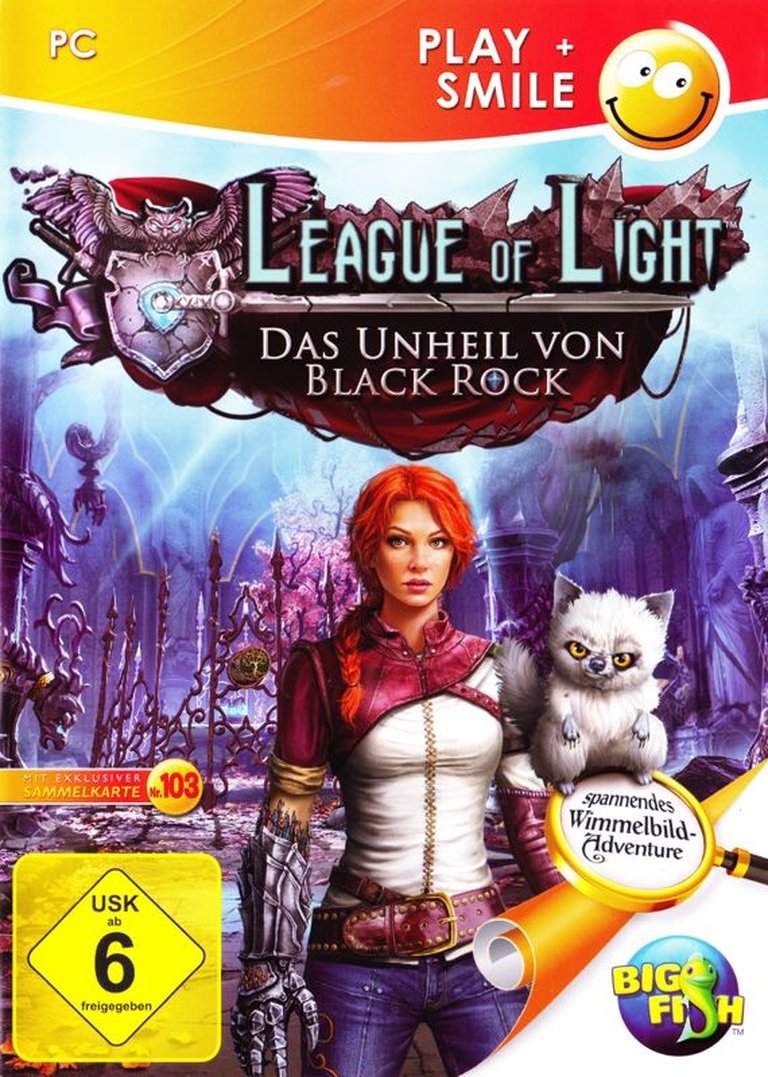

- Publisher: Big Fish Games, Inc

- Developer: Mariaglorum

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Puzzle elements

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

League of Light: Silent Mountain is a first-person adventure game with hidden object and puzzle elements, set in the mysterious town of Stoneville and its surrounding areas like Under the City and Blackrock. Players assume the role of a detective investigating a series of enigmatic events, solving puzzles and uncovering clues to reveal the truth and escape with their lives in this narrative-driven mystery.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy League of Light: Silent Mountain

PC

League of Light: Silent Mountain Guides & Walkthroughs

League of Light: Silent Mountain Reviews & Reception

howlongtobeat.com (80/100): Beautiful, engaging, not difficult. Pretty straightforward. One of the better ones.

League of Light: Silent Mountain: A Polished Petrification in the Casual Adventure Pantheon

Introduction: The League’s Latest Case

In the bustling ecosystem of mid-2010s casual gaming, few studios mastered the art of the polished, narrative-driven hidden object puzzle adventure (HOPA) like Mariaglorum. Following the success of their Mystery of the Ancients series, their League of Light franchise sought to carve a distinct identity with a recurring cast of mystical detectives. League of Light: Silent Mountain, the series’ second main entry, arrives as a quintessential product of its genre and era: a game of impeccable presentation and meticulous design that unfortunately cannot entirely escape the gravitational pull of its own formulaic constraints. This review will argue that while Silent Mountain is a masterclass in user-friendly HOPA craftsmanship—boasting stunning visuals, inventive puzzles, and a competent mystery—its legacy is ultimately that of a highly polished but conceptually safe title. It exemplifies the peak of a specific design philosophy that prioritized abundant, accessible content over meaningful innovation, reflecting both the strengths and the simmering stagnation of the casual adventure market circa 2015-2016.

Development History & Context: The Mariaglorum Method

The Studio and Its Vision: Mariaglorum, a Russian developer, had by 2015 established itself as a premier contractor for Big Fish Games, the dominant marketplace for casual digital downloads. Their expertise lay in creating large volumes of content with consistent, high-fidelity aesthetics. The League of Light series was their attempt to build an original intellectual property, moving from the standalone mysteries of Mystery of the Ancients to a saga featuring a persistent organization and recurring protagonist. Silent Mountain (Collector’s Edition, September 2015; Standard, July 2016) was developed during a period where the HOPA genre was mature, with clear tropes: a first-person perspective, a map for fast travel, tiered difficulty settings, and a two-tiered structure of hidden object scenes (HOPs) and inventory-based puzzles.

Technological and Market Constraints: The game was built for modest system requirements (DirectX 9, 1.6 GHz CPU, 1GB RAM), targeting the vast audience of older PCs and laptops. This necessitated a “slideshow” presentation style—static, beautifully rendered backgrounds from which players interact. The technological “constraint” was also a design choice: it allowed for incredibly detailed hand-painted scenes without the overhead of a real-time 3D engine. This era was the twilight of the Big Fish Games-dominated casual market before the mobile free-to-play boom irrevocably changed the landscape. Silent Mountain represents the apex of the “premium, one-time-purchase” model for HOPAs, complete with a Collector’s Edition stuffed with extras (artwork, collectible owls, a bonus chapter), a final echo of a disappearing retail-like mindset in digital distribution.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Mystery of Stone and Secrecy

Plot and Structure: The narrative, as outlined in the official description and revealed through gameplay, is a straightforward detective plot with a supernatural bent. The player, an unnamed top agent for the League of Light, is dispatched to the isolated Belgian town of Stoneville to find fellow agent Louise, who has gone missing with a powerful League artifact. The town is under a petrification curse, its inhabitants turned to stone, and menaced by “giants” and a shadowy figure known as the Devastator. The plot unfolds over five chapters, moving from the town’s outskirts to its underground, the villain’s lair at Blackrock, the healer’s district of Roland, and finally the confrontation at the Devastator’s sanctum. A bonus chapter in the Collector’s Edition serves as a prelude, introducing the “Shadow Guards.”

Characters and Dialogue: Characterization is functional rather than deep. The protagonist is a blank-slate avatar, with the notable innovation (from the Jayisgames review) of allowing players to choose a male, female, or no voice for the detective—a rare and appreciated touch of inclusivity for the genre. Louise, the missing agent, is primarily a MacGuffin; her agency is revealed only in the final act. Supporting characters—a paranoid balloonist, a healer, a town elder—are archetypal and exist to dispense items, quests, or exposition. The dialogue is serviceable, moving the plot forward without significant flair, though the same review praises the “remarkably excellent voice acting” that elevates the material, a common strength in Mariaglorum’s productions.

Themes and Symbolism: Thematically, Silent Mountain explores isolationism and buried guilt. Stoneville’s self-imposed secession from the world is tied to a collective secret—their attempt to harness or hide the power that eventually corrupted their town. The petrification metaphor is literal but can be read as the consequences of turning a blind eye to evil or attempting to control forces beyond one’s understanding. The League of Light itself represents institutional responsibility; the player is sent not just to rescue an agent but to clean up a magical crisis the locals failed to manage. The “Devastator” is a classic fallen-priest figure, using the town’s own magic against it, a narrative about corruption from within. However, these themes are presented with such genre-familiar efficiency that they rarely resonate beyond the moment-to-moment puzzle-solving.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Engine of Busywork

Core Loops and Puzzle Design: The gameplay is a rigorously structured cycle: arrive at a location, examine the scene, collect hidden objects in a list-based HOP, use those items to solve puzzles (sequencing, mechanical, tile-matching, symbol-based), unlock new areas via the map, and repeat. The walkthrough from Big Fish Games reveals a staggering density of interactions. A typical screen might involve: 1) finding a bucket, 2) using it to fill with water, 3) using the water on a rusty knife, 4) finding an oilcan to lubricate it, 5) using the knife to cut something, and so on. This creates a compulsion loop of constant, small rewards.

Innovation and Flaws: The game’s greatest strength is the variety and integration of its mini-games. Beyond standard HOPs, it features:

* Logic puzzles: The “token” puzzles (Anvil, Tongs) where tokens must be placed in a sequence based on cryptic clues.

* Mechanical puzzles: The pulley system, the crossbow with rope arrow, the boat navigation via compass/map.

* Pattern recognition: Rune placement on doors, symbol-matching on clocks, aligning stained glass pieces.

* Alchemy and crafting: Combining sulfur, gunpowder, wick, and vials to make dynamite; mixing paints to create new colors.

However, the Jayisgames review identifies the core flaw with surgical precision: “busywork.” The game is padlocked with artificial barriers. You can’t move hay because you’re “allergic,” requiring a pitchfork assembled from sticks. You can’t pick up a simple item because it’s under a rock requiring a lever. This transforms detective work into a game of “inventory shuffling” and “click-the-correct-prop.” The player is less a brilliant detective and more a compliant errand-runner for the game’s opaque logic. The puzzles are often clever, but the path to them is frequently cluttered with trivial, non-logical steps that stretch playtime without deepening engagement or narrative integration.

UI and Accessibility: The interface is a model of clarity. The customizable difficulty (relaxed vs. challenging modes, hint systems, skip puzzles) is excellent. The map is indispensable. The inventory is generally well-managed, though the sheer volume of collected items (decoupled decorative sword parts, multiple vials, countless runes and symbols) can become overwhelming, a common issue in lengthy HOPAs.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Valley of Petrified Beauty

Setting and Atmosphere: Stoneville is the game’s true star. The concept—a village literally and magically turned to stone—provides a stunning visual throughline. The art direction, led by Alexander Bekasov, capitalizes on this with exceptional environmental storytelling. One moment you’re in a bucolic, haunted farm; the next, in a subterranean cavern with luminous fungi; then a cliffside town with eerie, growing stone formations. The “menacing giants” are not just enemies but part of the ambient, corrupted landscape. The world feels lived-in and then abruptly un-lived-in due to the petrification, a powerful atmosphere conveyed entirely through static screens.

Visual Direction: The graphics are lavishly detailed, illustrated realism. Textures are rich: the roughness of stone, the grain of wood, the sheen of metal. The color palette shifts from melancholic blues and greys to the warm, sinister glow of magical corruption. The hidden object scenes are famously “busy” and layered, requiring players to peer into nooks and crannies, which is both a testament to the artists’ density of detail and a source of potential frustration. The character portraits, especially for the villain, are dramatic and expressive.

Sound Design and Music: The soundscape is a major asset. The background music is atmospheric and melodramatic, perfectly underscoring the mystery and dread. The “remarkably excellent voice acting” noted by beta testers is a standout; the performances, even for minor characters, are committed and clear, selling the supernatural stakes. Sound effects for interactions (clinks, rumbles, magical zaps) are crisp and satisfying. This audio-visual polish creates a sense of grandeur that belies the game’s casual genre label, making Stoneville feel like a place with real weight and history.

Reception & Legacy: A Niche Masterpiece

Critical and Commercial Reception: Upon release, League of Light: Silent Mountain was met with strongly positive reception within its target audience. Big Fish Games featured it as an “Editor’s Choice,” and beta tester quotes on the Steam store page (“Beautiful visual effects, music and voices were excellent…”) are indicative of its appeal. The Steam version holds a perfect 100% Player Score on Steambase from 8 reviews, though this is a tiny sample. The more critical (and likely more representative) voice comes from sites like Jayisgames, which praised its polish and creativity but bluntly criticized its “busywork” and predictable story, summarizing it as “doesn’t really do anything new, but everything it does, it does very well.” On aggregators like Metacritic, critic reviews are notably absent or sparse, reflecting the genre’s historical neglect by mainstream gaming press.

Legacy and Influence: Silent Mountain has no meaningful influence on the broader AAA or indie landscapes. Its legacy is internally focused within the HOPA genre. It set a high bar for production values—art, voice acting, and mini-game variety—that competitors like Eipix or Artifex Mundi would strive to match. It exemplifies the ” Collector’s Edition” model at its most extravagant (extensive bonuses, two bonus chapters across CE and standard?). However, it also crystallized the genre’s design rut: the relentless chain of trivial item combinations. Its immediate successor in the series, League of Light: The Gatherer (2017), and later entries like Edge of Justice (2018), appear to iterate on this same template without significant mechanical evolution. In the grand history of video games, Silent Mountain is a beautifully preserved artifact of a specific, commercially potent but creatively stagnant moment in casual adventure gaming. It is remembered fondly by its fans as a paragon of its type, but it did not transcend its type.

Conclusion: A Treasure Obscured by Its Own Gilding

League of Light: Silent Mountain is a game of profound contradictions. It is a breathtakingly beautiful, meticulously crafted point-and-click adventure with some of the most creative and satisfying puzzle designs in the HOPA genre. Its world is a captivating blend of gothic mystery and magical catastrophe, brought to life by expert art and sound. Yet, this brilliance is often dimmed by a suffocating layer of padded, illogical busywork that betrays a lack of faith in the player’s intelligence and the narrative’s own stakes. You are the League’s best detective, yet you must jump through hoops to move a piece of hay.

Its place in history is secure not as a revolutionary title, but as a culmination. It represents the peak of the “premium casual adventure” model—the last gasp of a genre that would soon be consumed by free-to-play mobile mechanics and endless-runner simplicity. For historians, it is a crystal-clear document: look here at what the genre could achieve in production quality,叙事凝聚力 (narrative cohesion), and puzzle craft; and look here at the creative dead end it reached by refusing to challenge its own structural assumptions. To play Silent Mountain is to experience a masterfully constructed prison. The walls are made of exquisite art and clever puzzles, but the bars are made of trite busywork. For those willing to accept the terms of its captivity, the view from within is still stunning. For the genre’s future, the door had to be kicked down.

Final Verdict: 7/10 — A quintessential, high-polish hidden object adventure that is best-in-class for its format but ultimately held back by the genre’s own design tropes. A must-play for genre enthusiasts, a curiosity for historians, and a lesson in “more” not always equaling “better.”