- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Developer: Casual Games

- Genre: Puzzle

- Gameplay: Falling block puzzle, Tile matching puzzle

Description

Alvin: Abenteuer im Puzzleland is a 2003 Windows puzzle game that combines Tetris-style falling block mechanics with match-3 tile matching. Set across five distinct worlds, players solve puzzles by ordering geometrical shapes to create disappearing rows or matching three identical symbols in a row, with each level requiring the achievement of a specific goal to progress.

Alvin: Abenteuer im Puzzleland: Review

Introduction

In the vast and often forgotten archives of early 2000s casual gaming, buried beneath the weight of industry-defining behemoths, lie the quiet relics of local market specificity—games designed not for global acclaim but for the shelves of a regional software aisle. Alvin: Abenteuer im Puzzleland, released in 2003 for Windows, is one such relic. Its existence, meticulously preserved on databases like MobyGames, represents a crucial if unassuming node in the network of European game development, particularly within the German-speaking “Abenteuer” (Adventure) series milieu. This review posits that the game’s primary historical significance is not as a landmark of design innovation but as a functional artifact of its time: a competent, hybrid puzzle compilation that leveraged the dual popularity of Tetris and match-3 mechanics, packaged for a children’s audience (USK 6) and distributed through niche channels. Its legacy is one of quiet service, a title that likely fulfilled its purpose as affordable, accessible entertainment without leaving a discernible mark on the evolution of its genres. Through an exhaustive dissection of the scant available data, we can reconstruct not a masterpiece, but a clear snapshot of a development philosophy—accessible, hybrid, and commercially pragmatic.

Development History & Context

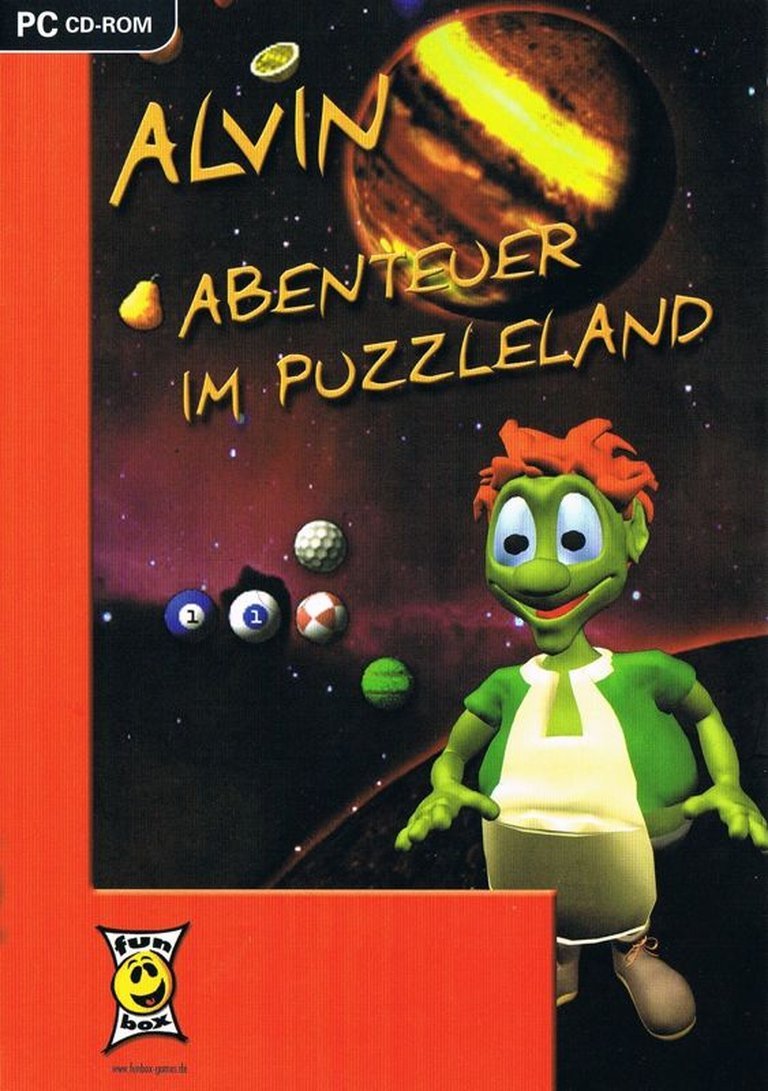

Studio & Vision: The game was developed by an entity simply credited as Casual Games. This is not a specific studio name in the traditional sense but appears to be a generic “developer” label used by its publisher, dtp digital tainment pool GmbH, a prominent German distributor known for budget-friendly “Fun Box” releases (as noted in the release info). The lead credits—Kristijan Dumančić (Lead Programmer) and Bartol Ruzic (Lead Artist)—along with two additional programmers, Ronny Knauth and Sebastian Tusk, point to a very small team, likely a core group within or contracted by dtp. Their vision, as distilled from the game’s description, was explicitly hybrid: to fuse two established, massively popular puzzle paradigms.

Technological & Market Constraints: 2003 was a pivotal year for casual PC gaming. Bejeweled had popularized the match-3 genre, and Tetris remained a timeless staple. The “Casual Games” label and the use of generic developer credits suggest a project with a tight budget and a short development cycle. The “Fixed / flip-screen” visual tag indicates a simple, screen-by-screen progression rather than a scrolling world, a common cost-saving measure. The reliance on Keyboard and Mouse as sole inputs reflects the standard PC casual game control scheme of the era. The game was sold as a Commercial product on CD-ROM, typical for the period before digital distribution dominated, and targeted at the German market (USK 6 rating, German title). It was part of a distribution strategy where dtp would bundle such titles in multi-game “Fun Box” collections, maximizing shelf presence and impulse buys.

Gaming Landscape: The puzzle genre was dominated by simple, addictive mechanics. Hybrid attempts were not uncommon (Tetrisphere on N64, various Dr. Mario entries), but a direct, menu-selectable switch between falling-block (Tetris) and tile-matching (match-3) within a single adventure framework was a niche approach. Its closest thematic relatives appear to be other German “Abenteuer” titles like Elfenwelt: Abenteuer im Elfenland (2001) and Pumuckls Abenteuer im Geisterschloss (2000), suggesting a franchise or brand strategy based on licensed or original characters navigating themed game worlds. Alvin likely existed in this ecosystem—a character-driven puzzle compilation for younger players.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

A Critical Vacuum: The source material is completely silent on narrative elements. MobyGames’ description provides only a mechanical summary: “Solve puzzles in 5 different worlds… Once you reach a certain goal, the level is complete.” There are no credits for writers, no listed characters beyond the titular “Alvin,” and no mention of plot, dialogue, or themes.

Inference from Title & Context: The title, Alvin: Abenteuer im Puzzleland (“Alvin: Adventure in Puzzleland”), and its series siblings suggest a framework common to children’s edutainment or simple adventure games of the era. Presumably, the player controls a character named Alvin who must traverse five distinct “worlds” (thematic puzzle sets). The narrative, if it existed at all, was almost certainly minimal: a framing device to justify the puzzle-solving, likely involving a quest to save or restore a fantastical “Puzzleland.” Given the USK 6 rating, the conflict would be trivial, the theme positive (friendship, perseverance, cleverness), and any dialogue simple and instructional. The “thematic” depth is therefore nonexistent in the source material; the “theme” is purely the act of puzzle-solving itself. This represents a stark contrast to narrative-driven adventure games of the same regional series, positioning Alvin as a pure mechanics-focused title.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The entire gameplay architecture is defined by MobyGames’ terse genre tags: “Falling block puzzle” and “Tile matching puzzle.”

Core Dual-Loop System:

1. Tetris-Style Falling Block: Players manipulate descending geometric shapes, rotating and placing them to create solid horizontal lines, which then disappear. Goals are presumably score-based or line-clear quotas.

2. Match-3 Tile Matching: Players swap adjacent symbols (likely themed icons) on a grid to create rows or columns of three or more identical items, which then vanish, with new tiles falling from above. Goals involve clearing a certain number of specific symbols, reaching a score, or clearing all “blocked” tiles.

Architecture & Progression: The description states the game is structured across “5 different worlds.” Each world likely contains a sequence of levels, with the type of puzzle (Tetris or match-3) possibly predetermined per level or selectable by the player. Progression is gated by achieving a “certain goal” per level—classic puzzle game design where success is binary (goal met/not met) rather than health-based. There is no suggestion of continuous lives or failure penalties beyond restarting the level.

Systems & UI: Based on the era and genre:

* User Interface: Likely a simple HUD showing score, level number, current goal (e.g., “Clear 20 red symbols”), and possibly a move or time limit.

* Character Progression: Almost certainly none. Puzzle games of this type typically offer static mechanics; player “progression” is purely skill-based and level-unlocking.

* Innovation vs. Flaw: The “innovation” is the packaging hybrid. The potential flaw is lack of integration: the two modes likely exist in isolation with separate rule sets, selected from a menu. There is no evidence of mechanics from one mode affecting the other, making it a compilation rather than a fused system. The “Fixed / flip-screen” visual type suggests discrete, static puzzle boards, which is standard for this genre but limits dynamic spatial puzzles.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Setting & Atmosphere: The “Puzzleland” concept implies a whimsical, abstract, or toy-like setting. With no screenshots or descriptive credits, the atmosphere must be inferred. Given the child-friendly USK 6 rating and the era’s casual game aesthetics, the art was almost certainly:

* Bright, saturated colors.

* Cartoonish, non-threatening visual style.

* Thematic consistency across the five worlds (e.g., a “Jungle” world with leaf patterns, a “Space” world with planets).

* Simple, clear iconography for match-3 symbols to ensure instant recognizability.

Visual Direction (Bartol Ruzic – Lead Artist): Ruzic’s other credits (on 18 games per MobyPlus) span titles like Gorasul (an RPG) and Soldiers of Anarchy (a tactical shooter), an unusually wide range. This suggests either a versatile artist or, more likely, a company where staff wore many hats. For Alvin, his direction was constrained by the puzzle genre’s need for functional clarity over artistic flourish. The art would prioritize readability of shapes and symbols over detailed sprites or environments. The “Fixed / flip-screen” design means each level is a static, composed image where the puzzle grid sits.

Sound Design: No sound credits are listed separately, implying it was handled by the core team or outsourced simply. The sound design would follow casual game conventions of the early 2000s:

* Music: Looping, cheerful, minimalist MIDI-style tracks, one per world, designed to be inoffensive and repetitive.

* SFX: Crisp, satisfying auditory feedback for core actions—a thud for piece placement, a chime or pop for matches/line clears, a positive ding for goal completion. The soundscape’s primary function is to reinforce correct player actions and provide a mild, non-intrusive backdrop.

Reception & Legacy

Critical & Commercial Reception (at launch): There is a total absence of contemporary critical or user reviews. Metacritic lists no critic or user reviews for the PC version. MobyGames shows only one player has “collected” the game in their database as of the last update. This vacuum is itself data: it indicates the game was a commercial non-event. It did not penetrate mainstream gaming press consciousness. Its release through dtp digital tainment pool GmbH’s “Fun Box” lines suggests it was a budget title, sold in multi-game packs at low prices in German-speaking countries (Germany, Austria, Switzerland). Its success was measured in units moved through these bundles, not in critical acclaim.

Evolution of Reputation: The game’s reputation has not evolved because it never had one to evolve. It remains a data point, cataloged by preservationist sites like MobyGames and archival projects like NSWTL.INFO (which merely repeats the basic metadata). Its continued existence in these databases is its primary legacy—a testament to the exhaustive work of documenting every commercial release, no matter how obscure.

Influence on Subsequent Games & Industry: There is zero evidence of any direct influence. The game did not pioneer a hybrid mechanic; Dr. Mario (1990) and later Puzzle League titles had already combined puzzle modes. Its straightforward, menu-based approach to offering two separate modes was a safe, derivative design choice. Its true influence is indirect and systemic:

1. It reflects the localization and regional publishing strategies of the early 2000s, where companies like dtp created or published games specifically for German-language markets with culturally resonant titles and retail partnerships.

2. It exemplifies the “budget casual compilation” model that prefigured today’s massive casual mobile game libraries, but for the physical PC retail space.

3. It stands as a counter-example in the history of puzzle games—a title that chose breadth (two genres) over depth, and in doing so, was rendered historically invisible compared to titles like Bejeweled or Tetris Attack that defined their respective lanes.

Conclusion

Alvin: Abenteuer im Puzzleland is, in the strictest academic sense, a complete historical artifact. We know its creators, its publisher, its release year, its platform, its genre tags, its rating, and its basic mechanical premise. We know it was a commercial product sold on CD-ROM in Germany. For this, it is preserved.

However, to assess it as a game—as an experience of play, as a work of creative expression—the available evidence is barren. There is no art to analyze beyond inferred style, no sound to critique, no narrative to dissect, no gameplay innovation to champion, and no reception to contextualize. It exists in a state of historical suspension, defined only by its metadata.

Therefore, the final verdict must be bifurcated:

* As a Historical Document: It is successful and significant. It perfectly illustrates a specific, low-budget, regionally-targeted segment of the 2003 PC game market. Its obscurity is its historical value as a data point about what did not achieve widespread recognition.

* As a Game: It is, by all functional indicators from the period, a competent but utterly forgettable hybrid puzzle compilation. It served its presumed purpose—providing simple, varied, child-friendly puzzles for the German “Fun Box” buyer—and was then discarded by time and memory. It did not fail; it simply was never meant to be remembered.

Its place in video game history is as a ghost in the machine, a title whose only lasting monument is a line in a database, reminding us of the vast, silent majority of games that built the industry’s foundation not with fame, but with quiet, commercial stock. To study Alvin is to study the texture of the unnoticed.