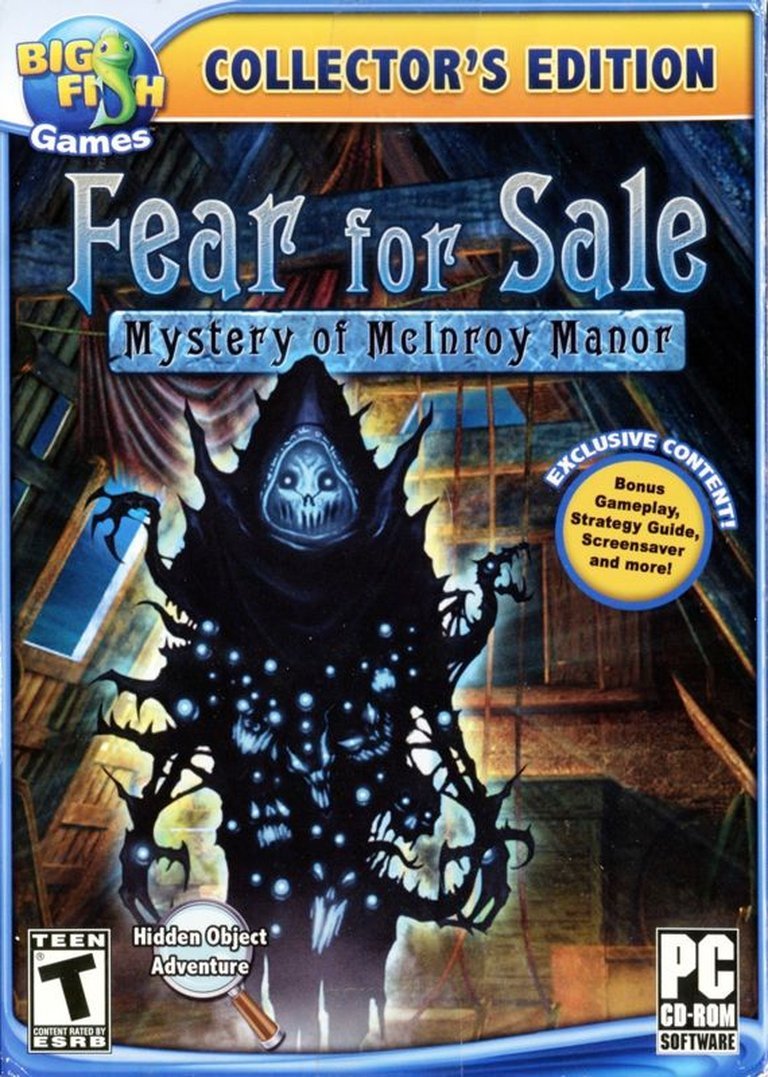

- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: iPad, iPhone, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Big Fish Games, Inc

- Developer: EleFun Multimedia Games

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Puzzle elements

Description

Fear for Sale: Mystery of McInroy Manor (Collector’s Edition) is a first-person hidden object adventure game set in the haunting McInroy Manor, where players explore the estate to investigate the tragic demise of the McInroy family and free their trapped souls. Through interactive puzzles and narrative-driven exploration, the game blends mystery-solving with atmospheric storytelling in a chilling, immersive experience.

Gameplay Videos

Fear for Sale: Mystery of McInroy Manor (Collector’s Edition) Guides & Walkthroughs

Fear for Sale: Mystery of McInroy Manor (Collector’s Edition): Review

Introduction: A Ghost in the Machine of Casual Gaming

In the sprawling ecosystem of 2010’s digital storefronts, few genres thrived with such quiet, relentless prosperity as the hidden object puzzle adventure (HOPA). It was the era of the “casual” revolution, a time when games like Clockwork Tales: Of Blades and Talons and Dark Parables defined the aesthetic and mechanical language of a million after-work decompression sessions. Into this crowded field stepped Fear for Sale: Mystery of McInRoy Manor (Collector’s Edition), a title that promised a “dark and mysterious” take on the formula from publisher Big Fish Games and developer EleFun Multimedia. This review posits that while McInroy Manor is a quintessential, and often formulaic, product of its time and business model, its execution—particularly in its Collector’s Edition packaging and its surprisingly dense puzzle ecology—reveals both the strengths and the entrenched limitations of the HOPA genre at its commercial zenith. It is not a forgotten masterpiece, but it is a perfectly preserved artifact of a specific moment in gaming history, offering a clear lens through which to view the craftsmanship, constraints, and creative bankruptcy of the early 2010s casual boom.

Development History & Context: The Russian Bear in the Big Fish Pond

To understand Fear for Sale, one must first understand the machine that produced it. The developer, EleFun Multimedia Games, was a prolific Russian studio, a key cog in the Eastern European outsourcing pipeline that powered much of Big Fish Games’ vast catalog. Credits from MobyGames list a tight-knit team: producers Alexey Belkin and Alexander Gulyaev, lead artist Sergey Shatokhin, and lead programmer Anton Gagarin. This was not a large, acclaimed studio but a specialized unit adept at working within tight technical and creative parameters. Their portfolio, visible through MobyPlus links, includes other Big Fish series like Witches’ Legacy and Superior Save, indicating a formulaic, assembly-line approach to genre production.

The technological constraints were those of the late-2000s PC casual market: pre-Steam dominance, reliant on Big Fish’s own download manager and CD-ROM distribution. System requirements (Windows XP/Vista/7, 1.0 GHz CPU, 256 MB RAM) were minimal, targeting low-spec household PCs. The game’s 886 MB footprint was substantial for the era but par for the course, filled with pre-rendered 2D backgrounds and simple 3D object models. Visually, it aimed for a “darkly atmospheric” gothic style, but the assets, as seen in promotional screenshots, show the soft, slightly blurry, and overly saturated art direction common to the period—efficient, mood-setting, but rarely achieving genuine visual dread.

Big Fish Games was the undisputed behemoth of casual distribution, a marketplace and subscription service (Game Club) that functioned as a curated app store before the App Store’s gaming dominance. Releasing a “Collector’s Edition” was their standard premium tier, bundling the base game with a strategy guide, extra gameplay, and digital wallpapers/screensavers. This model, directly reflected in McInroy Manor‘s listing, commodified completionism and fan service. The game’s legacy context is thus as a volume product: a reliably engaging, utterly predictable entry in the “haunted house” subgenre of HOPA, designed for frictionless consumption by a primarily female-identified audience seeking relaxed puzzle-solving. Its November 2010 release placed it in a crowded holiday season against other Big Fish tentpoles and Nancy Drew adventure titles, competing for the same player dollars with slight variations on a theme.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Haunted House by the Numbers

The plot of Fear for Sale: Mystery of McInroy Manor is a masterclass in genre convention, assembled from the most reliable components of Gothic melodrama and mystery serials. Players assume the role of Emma Roberts, a “press reporter” for the titular Fear for Sale Magazine. The setup is pure MacGuffin: Emma’s editor makes a “sizable donation” to the long-sealed McInroy estate to gain access for a story. This immediately establishes the game’s cynical, meta-textual relationship with its own “fear” branding—the horror is a commodity to be investigated and packaged.

The McInroy family tragedy unfolds through environmental storytelling and journal entries. We learn of Lord McInroy, a man with a dark past and a mysterious study; his wife, Lady Averill, who died under suspicious circumstances; and their two children, Julia and an unseen son. The narrative is structured around freeing the family’s trapped souls, a common trope in HOPA that transforms ghost stories into benevolent puzzles. The antagonist is Dr. Berk, the family physician, and a demonic entity he summoned in a “Resurrection Machine” in the family crypt. The twist—that the demon is bound not by ritual but by a simple logic puzzle-based keycard system—epitomizes the genre’s blending of supernatural lore with mundane puzzle-game logic.

Thematically, the game gestures at guilt, legacy, and forbidden knowledge. Lord McInroy’s “dreams of destroying the world” (as revealed in the final demon interrogation) are a cartoonish villain motive. Julia’s soul is freed by repairing a doll and placing it on a swing—an act of childhood restoration. Lady Averill’s death is linked to a poisoned tray, solved by a precise alchemical process involving topaz gems. The themes are never deeply explored; they are puzzle skins. The “fear” for sale is not existential dread but the pleasant, controlled anxiety of not knowing where the next hidden object is. The narrative is a skeletal spine upon which to hang item hunts and lock mechanisms, a functional framework that succeeds only in providing adequate justification for the player’s actions.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Engine of Addiction

Fear for Sale operates on a now-standard HOPA core gameplay loop: navigate static 2.5D scenes, find listed hidden objects, use acquired items to solve environmental puzzles, and advance the story. The game is divided into five main chapters plus a bonus “Extras” chapter in the Collector’s Edition, each with several distinct locations (manor exterior, foyer, boiler room, library, crypt, etc.).

Hidden Object Scenes (HOS) are the bread and butter. These are traditional “word list” scenes where players find items like “SCREWDRIVER,” “CANDLE,” or “PIRATE COIN” against cluttered, thematically appropriate backgrounds. The walkthroughs confirm the lists are dynamic, changing slightly per playthrough, a common tactic to encourage replay or simply obfuscate guides. The inventory system is a persistent scrollable bar at the bottom. A crucial innovation (or irritant, depending on perspective) is that many items found in HOS are immediately used on-site as part of the scene’s puzzle (e.g., finding a “KEY” to open a drawer within the same screen). This creates a tight, self-contained loop within each location.

The puzzle design is where the game reveals its true character. It is less about clever storytelling and more about inventory chaining and systemic interaction. The walkthrough is a 25,000-word testament to this. Players collect a HAMMER to break a headlight for a BULB, use a CROWBAR to get NAILS, combine PLANK + NAILS + HAMMER to make STAIRS, and so on. This creates a tangible sense of progression and “crafting,” though it is linear and deterministic. Stand-alone logic puzzles include:

* Circuit Puzzles: Rotating connectors to complete a circuit (Chapter 1).

* Lock Mechanisms: “Tumblers” where players must click symbols in a specific order (often random per playthrough, as notes indicate).

* Sliding Tile Puzzles: Reassembling a mirror or a drawing from pieces.

* Sequence Puzzles: Ordering cube-shaped symbols on a lock (used twice, with a fixed “anchor” column).

* Clock Puzzles: Aligning clock hands to zodiac symbols based on mirror clues.

* Gear Puzzles: Arranging physical gears on pegs to rotate a central gear.

The UI/UX is functional. The journal updates automatically with plot-critical notes and codes (e.g., the safe code “2-8-6-3” from under the stairs). The hint button has a cooldown. “Excessive random clicking” causes a cursor lock penalty—a gentle nudge against brute-forcing puzzles. The Collector’s Edition additions are significant: a fully integrated, clickable strategy guide (essentially the walkthrough provided by Big Fish), bonus screenshots, and a separate bonus chapter (“Doctor Berk’s Secret Study”) that extends the gameplay with more inventory chains and puzzles, adding several hours to the total.

Where the game shines is in the density and variety of its puzzle types. It rarely repeats the same mechanism twice in quick succession. Where it falters is in the utter lack of originality; every puzzle is a standard trope from the HOPA playbook. There is no “combat,” no failure states (you can’t die or run out of time), and no meaningful narrative branching. The “progression” is purely linear puzzle-solving. The game’s length (estimated 4-6 hours for the main story, plus bonus chapter) is achieved not through vast spaces but through the sheer number of interlocking item uses and puzzles.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Atmosphere as Asset

The setting of McInroy Manor and its grounds is a compendium of haunted house clichés: a decaying Gothic mansion, a spooky graveyard with a crypt, a dilapidated boat house, a boiler room with industrial machinery, a overgrown fountain courtyard. Each area is a self-contained puzzle hub. The atmosphere is entirely conveyed through the art direction and sound. The visual style is consistent: dimly lit, with a color palette of browns, greys, and deep blues. Light sources (lamps, fireplaces, the moon) create pools of illumination against darkness, a technique used to focus attention but also to hide object details in shadow—a double-edged sword that can lead to frustrating pixel-hunting.

The sound design is comprised of a looping, ominous ambient track and discrete sound effects (creaking doors, a barking dog, a mechanical whir). Voice acting is absent; all story is conveyed through text journals and dialogue boxes with character portraits. This is typical for the budget tier of HOPA. The sound is functional, creating a baseline of unease, but never memorable or dynamically responsive. The “jump scare” is replaced by the sudden, satisfying click of a solved puzzle or the chime of a found object.

The world-building is environmental and item-based. The journal is key, accumulating police reports, family letters, and research notes that flesh out the backstory. However, these texts are brief and formulaic. The true narrative is in the objects: a child’s doll, a broken mirror, a family portrait, a surgical toolkit. The game’s strongest environmental storytelling is in the puzzle integration—the fact that you must repair a bellows to blow dust off a drawing, or use a pound cake recipe (found hidden in a kitchen scene) as part of a gem-encrusting alchemical process. These moments create a fragile illusion of systemic world coherence, where the manor’s history and its puzzles feel momentarily linked.

Reception & Legacy: Niche Success, Lasting Formula

Fear for Sale: Mystery of McInroy Manor’s critical reception is almost non-existent in traditional outlets. On MobyGames, the Collector’s Edition has a 3.8/5 from 4 player ratings, with zero written reviews. The standard edition has a 4.0/5 from 2 ratings. This silence is deafening for a game with clear commercial distribution. Its commercial performance is hinted at by its physical presence: listings on eBay (from sellers like “elainebuth” and “VONETTA’S VINTAGE VARIETY”) as both new and used PC CD-ROMs for $5-$25, and its availability on digital storefronts like BigAntGames years later. This indicates steady, if unspectacular, sales within the Big Fish ecosystem—enough to justify a whole series (“Fear for Sale”) with sequels like Sunnyvale Story (2012).

Its influence on the industry is not in revolutionary mechanics but in perfecting a profitable, repeatable template. It exemplifies the “casual trilogy” of HOPA, adventure, and match-3 that dominated Big Fish’s catalog. It demonstrates the viability of the Collector’s Edition as a monetization strategy for a $6.99 base game, adding value through extras rather than changing core gameplay. The game’s legacy is as a competent practitioner of a style that would soon be eclipsed by mobile free-to-play models and more ambitious indie adventures. It represents the last gasps of the premium PC hidden object download, a format that thrived in the 2005-2012 window before mobile’s ascendancy.

Where it finds a faint echo is in the modern “cozy game” resurgence. Titles like Chants of Sennaar or The Case of the Golden Idol inherit the HOPA’s focus on observational puzzle-solving but divorce it from the stale object-hunt lists. McInroy Manor stands as a “before” picture: before quality-of-life improvements, before deeper narrative integration, before the genre’s decline into sheer repetitiveness. It is a museum piece of the form at its most standardized.

Conclusion: A Haunting Artifact of a Bygone Era

Fear for Sale: Mystery of McInroy Manor (Collector’s Edition) is not a game to be judged by the standards of narrative-driven or mechanically complex AAA titles. As a piece of game history, it is invaluable. It is a pristine specimen of the 2010 Big Fish HOPA, capturing the genre’s core promise: a low-stress, puzzle-filled escape into a spooky but ultimately safe fantasy. Its strengths are its relentless, varied puzzle pacing and its functional, atmospheric world. Its weaknesses are its derivative story, recycled mechanics, and lack of any genuine surprise or innovation.

For the historian, it is a case study in volume production. The walkthroughs—so detailed they constitute almost a second manual—reveal a game built not on emergent gameplay but on a meticulously planned, linear chain of item interactions. For the player, it offers exactly what it advertises: a lengthy, entirely competent hidden object experience with a bonus chapter and digital trinkets. It is the gaming equivalent of a well-made, predictable comfort food meal.

Its definitive place in video game history is as a benchmark of casual saturation. It shows the point where the HOPA formula had been so thoroughly codified that innovation was not the goal; reliability, production speed, and meeting player expectations were. It is a ghost not of a manor, but of an entire business model—a model built on downloadable puzzles, collector’s editions, and the soothing, repetitive click of finding a hidden spoon. In that, it is both utterly forgettable and profoundly representative. It is a game that is perfectly, completely, and revealingly of its time.