- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Windows

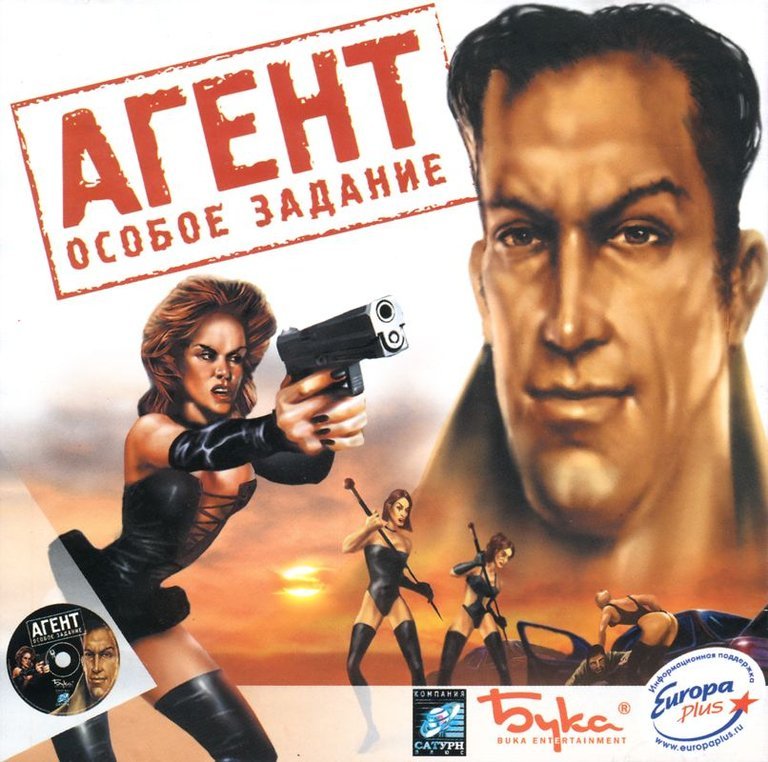

- Publisher: Buka Entertainment

- Developer: Saturn Plus

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Dialogue, Graphic adventure, Item collection, Point-and-click, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Fictional Russian resort

Description

Set in a fictional southern Russian resort, Agent: Osoboe zadanie is a 2D point-and-click adventure game where special agent Konstantin Gromov is sent to investigate a surge of violence triggered by a local mobster’s disappearance. Tasked with infiltrating two rival gangs—drug dealers and prostitutes—he must uncover the fate of a previous agent and decipher his chief’s hidden motives through exploration, item collection, and dialogue.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Agent: Osoboe zadanie

PC

Agent: Osoboe zadanie: A Deep Dive into a Post-Soviet Detective Niche

Introduction: The Curious Case of the Russian Resort Agent

In the sprawling, fragmented tapestry of global video game history, certain titles exist as vivid cultural artifacts—games not necessarily groundbreaking in their mechanics but profoundly illustrative of their time and place. Agent: Osoboe zadanie (Agent: Special Mission) is one such title. Released in February 2001 for Windows by the Ukrainian studio Saturn Plus and published by Buka Entertainment, this point-and-click adventure emerged from the unique, tumultuous soil of the post-Soviet gaming scene. It is a game that promises a gritty detective narrative set in a sun-drenched Russian resort town, yet one that is inextricably bound by the technical constraints and design philosophies of its era. This review posits that Agent: Osoboe zadanie is not a forgotten masterpiece but a crucial, representative specimen of the “Russian Quest” (russkiy kvest) genre—a game whose value lies less in universal acclaim and more in its authentic portrayal of a regional industry’s creative ambitions, its recurring pitfalls, and its enduring, if niche, legacy as a preserved piece of early 2000s CIS interactive storytelling.

Development History & Context: Saturn Plus and the “Russian Quest” Ecosystem

To understand Agent, one must first situate Saturn Plus. The studio, primarily known for its prolific work on the Petka (Petya) comedic adventure series and Dvenadtsat’ Stuljev (Twelve Chairs), was a titan of the Russian-language adventure game market in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Their output was characterized by a specific formula: 2D graphics, point-and-click interfaces, heavy reliance on inventory-based puzzles, and narratives steeped in local humor, satire, and occasionally, surrealism. Agent represents a notable departure from their signature farcical tone, attempting a serious detective thriller—a genre already saturated with classics like the Tex Murphy series or The Longest Journey in the West, but with distinct local flavor.

The technological context is one of transition. The game was developed for the tail end of the CD-ROM era, where full-motion video (FMV) and lavish 2D hand-drawn art were expensive luxuries. Saturn Plus worked within a 2D paradigm, utilizing static and side-scrolling backgrounds—a practical choice that minimized asset creation but imposed limitations on environmental interactivity. The development team, as listed in the credits, was a tight-knit group of approximately 38 developers. Key figures include Alexey Nikanorov, who wore multiple hats as Screenplay Author and Lead Artist, and Andrew Pershin, responsible for Music and Sound Effects. This concentration of roles is typical of smaller studios of the period, where artistic vision often directly dictated programming and design. The publishing partnership with Buka Entertainment, a major player in localizing and distributing Western games (like Warcraft and Diablo) in the CIS, provided crucial market access, while the co-publisher Discus hints at the complex, often regionally fragmented distribution networks of the time, especially regarding the Ukrainian market release documented in the Internet Archive entry.

The gaming landscape in Russia and Ukraine in 2001 was a paradox. Western AAA titles were slowly arriving via localization, but a robust, homegrown industry thrived on the adventure genre. This was due to lower development costs compared to 3D action games, a cultural affinity for narrative-driven experiences, and a nostalgic lineage tracing back to Soviet text adventures. Agent was thus born into a crowded field where it had to compete not with Half-Life, but with dozens of other similar-sounding, hand-crafted point-and-click titles from studios like K-D Lab (later Nival) and Akella.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Resort Town of Shadows

The plot, as synopsized on MobyGames and the official Saturn Plus site, is straightforward: Special Agent Konstantin Gromov is dispatched to a fictional southern Russian resort town, now gripped by gang violence following the disappearance of a local mobster. His mission is to infiltrate and gain the trust of two warring factions—one representing drug dealers, the other prostitutes—to uncover the fate of a previous agent and determine his chief’s true motives.

Plot Structure and Pacing: The narrative operates on a classic spy thriller framework but is delivered through the episodic, location-hopping structure of a point-and-click adventure. The story’s progression is entirely gated by puzzle solutions and dialogue trees, a common genre trait that inherently impacts pacing. Reviews from the period are telling. Game.EXE (78%) notably criticizes the game for a fundamental flaw: while the premise is engaging, the “action” (plot progression) is confined almost exclusively to “inserted, like teeth, video clips” (вставных, как зубы, роликах). This suggests the narrative is not organically unfolded through gameplay but is periodically delivered via non-interactive cutscenes, a common cost-saving and storytelling technique of the era that often breaks immersion.

Characters and Dialogue: Protagonist Konstantin Gromov is a classic hard-boiled archetype, a man of few words operating in a morally grey world. The supporting cast consists of archetypal gangland figures and resort town eccentrics. The dialogue, likely written by Nikanorov, aims for a mix of noir cynicism and post-Soviet gritty realism. The limited voice cast—only Alexander Filchenko and Victor Golovanov are credited as actors—means character expression is reliant on text and static portraits, further emphasizing the game’s 2D, non-real-time nature.

Underlying Themes: Beneath the detective plot, the game touches on several resonant post-Soviet themes:

1. Transition and Lawlessness: The resort town, a symbol of pre-revolutionary luxury twisted into a modern den of vice, mirrors the societal transformation of the 1990s, where old structures collapsed and new, often criminal, powers filled the vacuum.

2. Corruption and Betrayal: The central mystery—what happened to the previous agent, and what does the chief really want?—points to institutional rot. Gromov’s mission is not just about solving a crime but navigating a labyrinth of potential betrayal from his own side, a common trope in Russian crime fiction reflecting public disillusionment.

3. Dualities: The split between the drug dealers and prostitutes gangs, the resort’s exterior beauty versus its internal corruption, Gromov’s official duty versus his personal survival—all speak to a world of stark contrasts. The Absolute Games review (55%) cynically references this with its quote: “Iskusstvo i sila — vot klyuchi ko vsem dveryam” (Art and Strength are the keys to all doors), followed by a subversive image of a stone urn being thrown through gates—a perfect encapsulation of the game’s likely theme: in a broken world, brute force (or cynical pragmatism) often trumps noble ideals.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Point-and-Click Crucible

Agent adheres strictly to the point-and-click adventure template of its time, with specific refinements and limitations.

Core Gameplay Loop: Players navigate Gromov through a series of static or horizontally/vertically scrolling 2D screens (locations like hotel lobbies, beaches, back alleys). Interaction is handled via a context-sensitive cursor with four states—Walk, Look at, Interact with, Talk—which auto-select when hovering over interactive hotspots, a standard quality-of-life feature. The loop is the genre holy trinity: Examine > Collect > Use/Dialogue > Progress. Inventory management is central.

Combat and Stealth: The description and reviews make no mention of traditional combat mechanics. In keeping with its genre, conflict resolution is almost certainly puzzle-based or dialogue-based. The “wave of violence” in the plot likely serves as atmospheric backdrop and motivation for certain actions (e.g., finding a weapon to bypass a guard, crafting an alibi), rather than involving direct action sequences. This aligns with the “Graphic adventure” and “Puzzle elements” tags on MobyGames.

Character Progression: There is no indication of RPG-like stats or skill trees. Progression is purely nonlinear and narrative-driven. “Gaining confidence” of the gangs is a metaphor for completing quests for NPCs, acquiring key items, and choosing correct dialogue options to advance the plot. The character’s “growth” is measured in plot milestones, not statistical upgrades.

Innovative or Flawed Systems: The reviews provide the sharpest critique here. Game.EXE‘s damning assessment is that the game violates fundamental “kquest commandments”: it hides unrelated items in the same screen, asks the player to perform useless actions, and creates illogical search puzzles (the specific example of searching for stolen linen while a drunk sits on it). This points to poor puzzle design and arbitrary object interactions—a chronic disease in many non-Western adventure games of the era, where developer logic often failed to align with player intuition. Conversely, Igray.ru (70%) counters that the game has “human logic” (человеческая логика прохождения), suggesting a divide in player expectation. This schism is the core of the gameplay debate: is the puzzle chain intuitive or obtuse? The 68% average critic score reflects this middling equilibrium.

Interface: The auto-selecting cursor is a positive. However, the broader UI—inventory screens, dialogue trees—is not detailed in sources. Given the era and region, it was likely functional but visually dated compared to contemporaries like Grim Fandango or The Longest Journey.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Look and Feel of a Fictional Resort

This is where Agent likely garners its most consistent praise.

Visual Direction & Art: With Alexey Nikanorov as Lead Artist and a dedicated team of Background Artists (Nikolai Mesheryakov, Denis Zaitsev) and Animators (including Vera Lushchik, Margarita Zverintseva, etc.), the game represents a concerted 2D artistic effort. The style is not described, but context is key. Saturn Plus’s work on the Petka series featured a cartoony, exaggerated aesthetic. Agent‘s shift to a detective thriller suggests a more grounded, perhaps photorealistic-painterly approach for backgrounds, with sprites for characters. The credit for 3D Animation (Vadim Zhiltsov, Vladislav Goncharov) is fascinating—it implies the use of pre-rendered 3D models for character animations or specific set pieces, a hybrid technique used to add dynamism within a 2D framework (seen in games like Grim Fandango). The Internet Archive description explicitly calls it a “classic example of the ‘Russian Quest’ genre… with visual style and humor of that era,” cementing its art as a time capsule.

Atmosphere & Setting: The fictional southern Russian resort is a brilliant narrative device. It allows for a juxtaposition of idyllic seaside imagery (舒展/beach scenes) with the seedy underbelly of gang wars. This duality is central to the atmosphere—a place of leisure corrupted by violence and greed. The setting avoids being a generic city; its specific “resort” identity adds a layer of social satire (the wealthy vs. the criminal underworld serving them).

Sound Design & Music: Andrew Pershin composed the music and sound effects. In an era of MIDI soundtracks and limited sampled audio, the score likely aimed for moody, atmospheric tracks—perhaps jazz-inflected for noir moments or tense, ambient drones for suspense. Voice acting is minimal (only two actors credited), meaning most dialogue is text-based, with occasional grunts or exclamations for actions. The sound design would focus on environmental cues: seagulls, waves, club music, gunshots (implied), to sell the resort setting and tense situations.

These elements collectively strive for an immersive, if static, world. The art is the game’s strongest asset in selling its unique locale and tone, even if the underlying systems sometimes falter.

Reception & Legacy: The 68% Enigma

Upon release in February 2001, Agent received a mixed critical reception, perfectly encapsulated by its 68% average from three contemporary Russian critics:

- Game.EXE (78%) praised its competent execution but delivered a severe critique of its design philosophy, calling out its reliance on non-interactive cutscenes and poor puzzle logic (“kvestovyye zapovedi”).

- Igray.ru (70%) offered a more forgiving review, calling it a “wonderful quest” with “excellent graphics and animation,” a good plot, and human logic—essentially recommending it as a quintessentially Russian adventure experience.

- Absolute Games (55%) was the most scathing, not for technical failings but for creative stagnation. The review lambasts the industry’s reliance on outdated stylistic tropes (“Vыodem na麓nuju иллюминацию”), famously quoting the protagonist’s line about “art and strength” to ironically critique the developers’ lack of innovation. This critic saw the game as symptomatic of a stagnant genre, crying “Give way to the young!”

Commercial Performance & Player Reception: No sales figures exist, but the modest collection count on MobyGames (8 collectors) and the absence of widespread re-releases until recent preservation efforts suggest it was neither a breakout hit nor a complete flop—likely a solid regional seller within its niche. The player rating average of 4.5/5 (from only two ratings) indicates those who sought it out and played it were generally satisfied, a common phenomenon for cult genre titles.

Legacy and Influence: Globally, Agent is obscure. It had no significant impact on Western adventure game development. Its legacy is regional and preservationist:

1. A Genre Time Capsule: It stands as a clear example of the mature, pre-decline phase of the “Russian Quest.” It tried to be serious where its peers often were comedic, but it still suffered from the same systemic design issues (arbitrary puzzles, cutscene-heavy storytelling).

2. Preservation Archetype: The existence of a high-fidelity 1200 DPI scan and ISO image on the Internet Archive—specifically noted as part of the “Pravdyvtsev.A.K Software Preservation Archive” for Ukrainian/CIS regional releases—is its most significant modern legacy. This digital preservation effort, documenting its Ukrainian-exclusive release and three-company publishing (Buka, Saturn Plus, Discus), transforms it from a forgotten game into a primary source document for historians studying regional software distribution, copyright notices, and physical media topology of the early 2000s CIS.

3. Cultural Footprint: It is listed on GOG’s Dreamlist and various databases (LaunchBox, SteamDB), indicating a persistent, quiet demand from retro gaming enthusiasts focused on Eastern European titles. Its association with Saturn Plus links it to a wider oeuvre (Petka, Red Comrades, Nedetskie Skazki) that forms a bedrock of a specific comedic/satirical adventure tradition.

Conclusion: verdict from the Archive

Agent: Osoboe zadanie is not a game to be judged by universal standards of design or storytelling. It is, instead, an artifact of a specific ecosystem—the early 2000s Ukrainian/Russian point-and-click adventure industry. Its strengths are rooted in its period: a committed 2D artistic effort, a premise that taps into post-Soviet societal anxieties, and a dedicated regional fanbase that appreciated its “human logic.” Its fatal flaws—the oft-criticized puzzle design and over-reliance on non-interactive narrative delivery—are the very symptoms of the genre’s insularity and resource constraints.

Its ultimate place in history is not as a classic, but as a preserved specimen. For the game historian, it is invaluable. The meticulously scanned CD-ROM in the Internet Archive, with its Ukrainian regional markings and triple publisher logos, offers more insight into the business of regional game publishing than the game itself offers in interactivity. For the enthusiast, it is a curious, flawed window into a world of resorts, gangsters, and agents that existed parallel to the Western gaming mainstream. One should approach it not with the expectation of a Gabriel Knight or a Broken Sword, but as one would a well-preserved, slightly corroded Soviet-era detective novel—appreciating its local color, its historical context, and the genuine craft that went into its making, while acknowledging that its puzzles may, as one critic noted, truly violate the commandments of good adventure design. Its final verdict is a qualified recommendation: essential for preservationists and cultural historians, a curio for genre completists, and a dated puzzle-box for the exceptionally patient.