- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Digital Clay Studios, LLC

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden object

Description

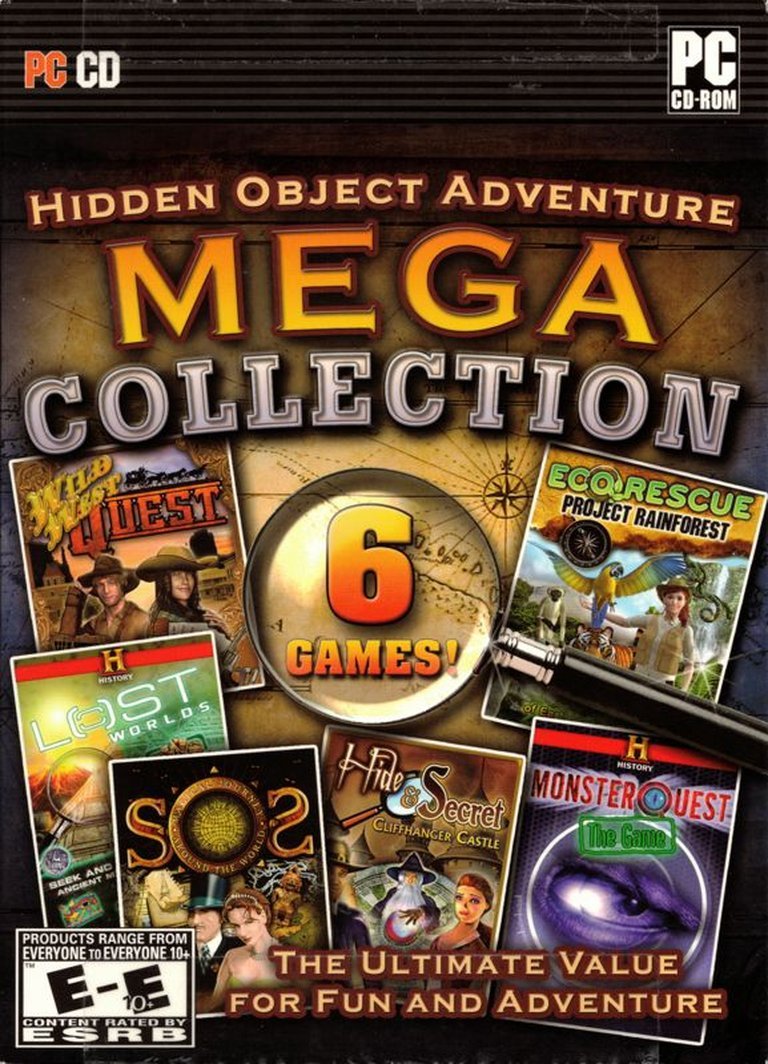

Hidden Object Adventure: Mega Collection is a compilation of six hidden object games, including EcoRescue: Project Rainforest, Hide & Secret 2: Cliffhanger Castle, MonsterQuest, Save Our Spirit, The History Channel: Lost Worlds, and Wild West Quest. This bundle offers diverse adventures—from environmental and supernatural mysteries to historical and western settings—where players search for hidden items in intricately designed scenes, blending casual puzzle gameplay with light narrative elements.

Hidden Object Adventure: Mega Collection: A Time Capsule of Casual Gaming’s Golden Age

Introduction: The Quiet Giant of a Genre

In the sprawling ecosystem of video game history, some of the most significant artifacts are not the AAA blockbusters that dominate headlines, but the mass-market phenomena that quietly defined eras. The hidden object game (HOG) genre, a pillar of the “casual gaming” boom of the 2000s and 2010s, is one such phenomenon. At its zenith, it was a dominion of cozy mystery, gentle puzzle-solving, and accessible playstyles, primarily attracting an audience of women over 40—a demographic historically underserved by the industry. Hidden Object Adventure: Mega Collection, a 2010 PC compilation released by the obscure publisher Digital Clay Studios, LLC, is not a landmark title in its own right. It features no revolutionary mechanics, no celebrated narrative, and received no critical attention. Yet, as a curated bundle of six titles from 2008–2009, it serves as an invaluable time capsule. This collection captures the HOG genre at a crucial inflection point: firmly established, commercially dominant, but on the cusp of a significant evolution in storytelling and design. This review will argue that Mega Collection is not a game to be judged by traditional metrics of artistry or innovation, but a historical document that exemplifies the conventions, constraints, and commercial logic of the hidden object puzzle adventure (HOPA) genre at its peak of physical-media popularity.

Development History & Context: The Assembly Line of Escapism

To understand Hidden Object Adventure: Mega Collection, one must first understand the ecosystem that birthed it. The game is not a unified product from a single studio but a compilation, a “greatest hits” package assembled by Digital Clay Studios, LLC. This publisher’s profile is minimal; they appear to have specialized in bundling existing casual titles, likely acquiring licensing or distribution rights from the original developers. The six included games—Wild West Quest (2008), Save Our Spirit (2009), Hide & Secret 2: Cliffhanger Castle (2008), The History Channel: Lost Worlds (2008), EcoRescue: Project Rainforest (2009), and MonsterQuest (2008)—were all released in the preceding two years by various, now largely uncredited, studios.

This period, 2008–2010, represents the height of the casual PC gaming boom and the physical CD-ROM’s last stand in that market. The genre’s undisputed king was Big Fish Games, whose Mystery Case Files series (beginning with Huntsville in 2005) had standardized the HOPA formula. As detailed in the Hidden Object Games Wiki, Big Fish Studios internalized development until 2012’s Shadow Lake, after which they shifted to a publishing model for other studios. Mega Collection stems from this second wave: games developed by smaller, often anonymous teams (potentially in Eastern Europe or Asia, common outsourcing hubs for casual games) to fill a voracious demand.

The technological constraints were those of the mid-to-late 2000s casual market: development for Windows XP/Vista, DVD/CD-ROM media, and modest hardware requirements (2D pre-rendered or simple 3D art, Flash-like interactivity). The business model was straightforward: sell a boxed compilation at retail (or via eBay, as current listings show) for a budget price ($19.85–$25.20). This was the era before “free-to-play” and mobile dominance (the iPhone launched in 2007, but the casual market was still PC-dominant). The compilation format itself was a sign of market saturation—publishers like Digital Clay aggregated existing properties to create a perceived value proposition for time-strapped or cost-conscious consumers.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Story as Scaffolding

The narrative design of the Mega Collection titles is best understood through the lens of the genre’s evolution, as expertly documented by narrative designer Lisa Brunette in SPAG magazine. In 2008-2009, the typical HOPA narrative was text-heavy and functionally separate from gameplay. Brunette describes this era’s approach: “The story was text-based, and the gameplay was a visual experience… The typical in-game journal serving as the vehicle for story.” Players would encounter a basic premise—a missing person, a haunted estate, an environmental crisis—and progress through the game by finding objects that unlocked new journal entries, which in turn provided context for the next scene.

Analyzing the thematic diversity of the Mega Collection reveals the genre’s attempt to cover every popular casual niche:

* MonsterQuest and Hide & Secret 2 tap into supernatural mystery, leveraging gothic tropes (castles, monsters, curses) that were a staple of the genre, influenced by series like Mystery Case Files: Ravenhearst.

* The History Channel: Lost Worlds is a clear licensed/brand extension title. Its narrative is likely an educational veneer over a standard HOG structure, using the History Channel’s credibility to attract a broader audience. This follows a trend seen in other licensed HOGs (e.g., National Geographic partnerships for Hidden Expedition).

* EcoRescue: Project Rainforest represents the “cause” or “message” subgenre, using gameplay to promote environmental awareness—a trend that would grow.

* Wild West Quest and Save Our Spirit fit into historical adventure and paranormal investigation archetypes, respectively.

Underlying themes across these games are consistent: restoration (saving spirits, rescuing rainforests), uncovering hidden truths (lost worlds, secrets of castles), and light justice (apprehending monsters or solving mysteries). The stories are universally plot-light and character-lite; the player is an anonymous stand-in, and cutscenes, where they exist, are minimal. The narrative’s primary function is to provide a reason for the core gameplay loop of clicking on objects. As Brunette notes, this would change dramatically post-2011, with a push to “reduce the amount of text” and integrate story visually through more frequent, impactful cutscenes and environmental storytelling. The Mega Collection titles stand as examples of the “separate” model—the story is something you read between searches, not something you experience through them.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Unchanging Core

The Mega Collection is, by definition, a compilation of six distinct games, but their core mechanics are virtually identical, representing the standardized HOPA loop of the late 2000s. Deconstructing this loop reveals a system designed for maximum accessibility and minimal friction.

1. The Hidden Object Scene (HOS): This is the heart of the experience. Players are presented with a static, highly detailed, clutter-filled illustration of a location (a castle hall, a jungle ruin, a saloon). A list of objects—either by name, silhouette, or anagram—is provided. The task is to locate and click each item. As detailed in the VOKI Games development blog, the creation of these scenes was a meticulous, multi-stage process involving reference gathering, sketching, 3D modeling, 2D texturing, animation, and “objecting” (placing hidden items). The design philosophy was clear: items must be visible but cleverly concealed within the scene’s logic (“a family coat of arms sewn onto a sofa cushion” vs. “a globe behind a cabinet”). The compilation’s value lies in offering dozens of such scenes across six different thematic settings.

2. The Adventure/Quest Layer: Between HOSs, players navigate a simple node-based map or a series of static “rooms.” This is the “adventure” component. Progress is gated by three common mechanics:

* Object Retrieval and Use: An item found in one scene (e.g., a key) is stored in an inventory and used in a later scene to unlock an area or solve a puzzle.

* “Door” or Area Unlocking Puzzles: Brunette identifies the “door puzzle” as the quintessential linearity control. A mini-game (often a simple tile-matching, jigsaw, or slider puzzle) must be completed to unlock the next major area, providing a clear progression path and preventingplayer overwhelm.

* Journal/Log Updates: Finding key items or completing scenes unlocks text entries in a journal, which is the primary vehicle for narrative delivery in these titles.

3. Additional Mechanics: The games would sprinkle in minor variations—silhouette searches, timed modes, “find the differences” puzzles between two scenes—to provide pacing. However, the compilation itself offers no systemic innovation. There is no character progression (no skill trees, no leveling), no combat in the traditional sense, and no meaningful choices affecting the story. The “systems” are purely the repeatable cycle of: Scene -> List -> Find -> Inventory/Journal Update -> Next Scene.

4. User Interface (UI): The UI is minimalist and functional: a list of required items, an inventory bar (often at the bottom), a hint button (with a cooldown), and a menu. This reflects the genre’s design for absolute beginners and an older demographic (the “women over 40” market Brunette mentions), prioritizing clarity over flair.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Aesthetic Cohesion Over Innovation

The visual and auditory presentation of the Mega Collection is a product of its time and budget. The art style across the six titles follows the mid-2000s casual game aesthetic: high-detail, hand-painted (or 3D-rendered and painted over) scenes with a warm, slightly oversaturated color palette. The goal was “beautifully detailed graphics” that made the hidden object hunt satisfying, as VOKI Games notes. However, quality varies. Titles like The History Channel: Lost Worlds would leverage stock photography and archaeological diagrams, while MonsterQuest might employ darker, moodier tones. The limitation is asset reuse and homogeneity; many scenes within a single game, let alone across a compilation, feel samey in composition and lighting.

World-building is primarily purely aesthetic and contextual. The “Wild West” theme means saloons, canyons, and wagons; “EcoRescue” means lush, vibrant jungles. The settings serve to justify the object lists (e.g., finding a rope and pickaxe in a mine, a ceremonial mask in a temple). There is little deep environmental storytelling because the medium prioritizes object search over exploration. The world is a series of dioramas, not a continuous space.

Sound design is functional atmospheric support: a looping, unobtrusive ambient track (mysterious music for spooky games, adventurous tunes for quests) and basic sound effects for clicks, hints, and item discoveries. Voice acting, if present at all in these 2008–2009 titles, would be sparse and likely limited to intro/outro cinematics—a stark contrast to the fully voiced characters of later HOPAs. The audio’s role is to polish the experience, not to narrate it.

Reception & Legacy: A Silent Artifact in a Noisy Genre

Hidden Object Adventure: Mega Collection exists in a curious critical vacuum. Metacritic lists no critic reviews, and MobyGames shows no user reviews for the specific compilation. Its eBay listings (the primary modern sales channel) feature sparse, generic praise (“great games to play,” “awesome thanks”). This silence is itself data: the compilation was a low-stakes, budget-purchase commodity, not a title that warranted critical dissection. It was aimed at a demographic that bought games based on box art and theme, not reviews.

Its commercial reception was likely modest but indicative of a healthy market. The late 2000s saw HOGs as a cash cow for publishers like Big Fish, PopCap, and GameHouse. Compilations like this (MobyGames lists numerous similar bundles: Hidden Object Collection, World Exploration Hidden Object Collection) were common, targeting consumers who wanted a bulk discount on casual gaming’s equivalent of “beach reads.” The $19.95 price point for six games was a compelling value.

Its legacy is one of being a transitional specimen. The included games (2008–2009) sit at the end of the “text-journal” era Brunette describes. By 2011-2012, she notes, the industry was aggressively reducing word counts and integrating visual storytelling. The Mega Collection titles are pre-evolution. They lack the integrated cutscenes, character arcs, and “woven tapestry” of text and visuals that defined superior HOPAs like later Mystery Case Files entries or Puppet Show: The Price of Immortality (2015). Furthermore, its physical CD-ROM format in 2010 was already becoming anachronistic. Digital distribution portals (Big Fish’s own, Steam) were ascendant, offering individual titles for $6.99-$9.99, making bulky, inflexible compilations less convenient.

Conclusion: Verdict – A Historical Specimen, Not a Classic

Hidden Object Adventure: Mega Collection is not a game one plays for artistic merit or mechanical novelty. It is a functional, unpretentious product of its time—a period when the hidden object genre was a commercial engine churning out competent, thematically diverse, and narratively thin puzzle experiences for a mainstream audience. As a player, experiencing it today offers little in the way of surprise or delight; the gameplay is repetitive, the stories are rudimentary, and the presentation is dated.

However, as a work of historiography, it is significant. It perfectly encapsulates the genre’s state in the late 2000s: the separation of narrative (text journals) and gameplay (HOS loops), the reliance on thematic branding (History Channel, Wild West), the standardized “door puzzle” progression, and the physical compilation sales model. It stands on the precipice of the genre’s maturation—the very next few years would see HOPAs become more cinematic, more visually integrated, and more narratively sophisticated, as Brunette’s team worked to reduce text and “treat words as a precious resource.”

Therefore, the final verdict is this: Hidden Object Adventure: Mega Collection is a 2-star game but a 4-star historical artifact. It is not a recommended play for the modern gamer seeking engagement. But for the scholar of casual gaming, the rise of the HOPA, or early 2010s PC retail, it is a perfectly preserved specimen. It demonstrates how a genre can achieve massive popularity through consistency, accessibility, and efficient, assembly-line design, long before it earns critical respectability. Its true value is not in the hidden objects within its scenes, but in the truths about an era of gaming it reveals to those who look closely.