- Release Year: 2024

- Platforms: Windows

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Gameplay: Tile matching puzzle

- Setting: Europe, Museum

Description

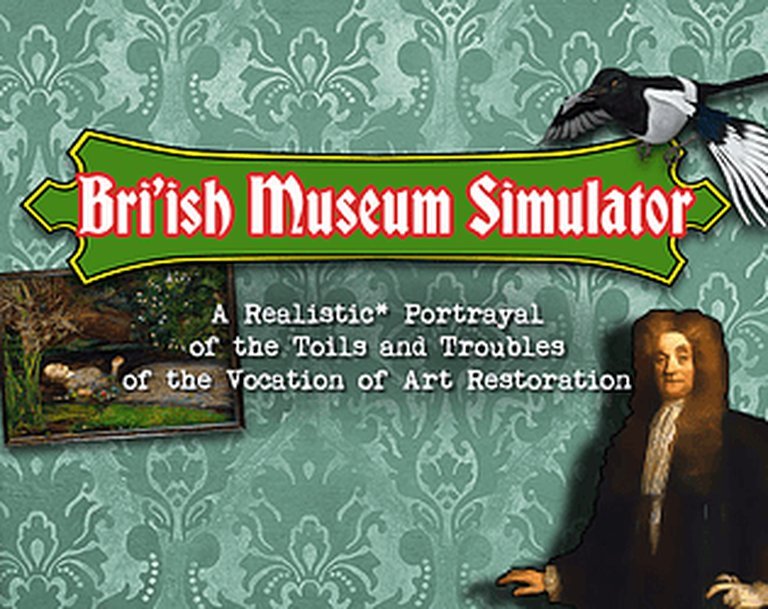

Bri’ish Museum Simulator is a first-person puzzle game set in a European museum where the player assists an employer in restoring historical art pieces through tile-swapping challenges. Each puzzle involves revealing shuffled images within a move limit, with golden eggs helping to reduce a debt, all framed by comedic dialogue between the player and their employer.

Bri’ish Museum Simulator: A Masterclass in Indie Satire and Puzzle Design

Introduction: The Art of Satirical Subtraction

Bri’ish Museum Simulator emerges not as a blockbuster historical epic but as a razor-sharp, concise indie parable that uses the seemingly benign mechanics of art restoration to expose the absurdities and ethical queasiness of institutional museology. Released in June 2024 by the enigmatic solo developer RagnarRox, this free-to-play title on itch.io is a masterclass in doing more with less. Its thesis is elegantly simple: by framing the mundane, repetitive labor of tile-matching puzzle-solving within a narrative of indentured servitude and cultural appropriation, it transforms a casual game into a pointed critique of the very institutions that claim to steward human heritage. It is a game that understands, as the academic Alexander Vandewalle argues in his analysis of video games as “mythology museums,” that the collection and presentation of artifacts—whether mythical or artistic—are never neutral acts. Bri’ish Museum Simulator weaponizes this neutrality, making the player complicit in the very processes it satirizes.

Development History & Context: Godot, Pandora’s Box, and the Power of a Punchline

Developed in the accessible, open-source Godot Engine, Bri’ish Museum Simulator is a product of the contemporary indie scene’s capacity for agile, concept-driven creation. The developer, RagnarRox, operates with a clear, focused vision, eschewing the scope creep that plagues many projects. The game’s core puzzle mechanic is openly acknowledged as being inspired by a classic: the tile-swapping puzzles from Alexey Pajitnov’s Pandora’s Box (1999), the Windows 95 multimedia title created by the inventor of Tetris. This lineage is crucial—it roots the game in a tradition of puzzle design that emphasizes simple, intuitive rules generating elegant complexity. However, where Pandora’s Box celebrated geometric beauty and historical art, Bri’ish Museum Simulator marries that mechanic to a sharply satirical narrative framework. Released at a time when conversations about museum decolonization, artifact repatriation, and the ethics of collecting are prominent in cultural discourse, the game’s timing is impeccable. Its technological constraints—fixed/flip-screen visuals, point-and-click interface—are not limitations but aesthetic choices that evoke a retro, almost archival feel, reinforcing its thematic concerns with preservation and display.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Debt, Demigods, and the Labor of “Restoration”

The narrative of Bri’ish Museum Simulator is delivered through sparse but combustible dialogue between the player-character (an unnamed, evidently desperate individual) and their employer, the fabulously named Hans Archibald van Dubenschmitz. Van Dubenschmitz is a character of breathtakingly convenient Eurasian heritage, a self-styled curator operating the eponymous “Bri’ish Museum™,” a name dripping with ironic, colonial posturing. The premise is brutally clear: the player is indentured, working off a debt by “restoring” a collection of appropriated art. The satire operates on multiple levels:

- Labor Exploitation: The core gameplay loop—performing repetitive, cognitively demanding tile-swaps—is directly tied to escaping “indentured servitude.” The golden eggs hidden within the puzzles are not mere collectibles; they are literal wages, each discovery paying down the player’s debt. This mechanically embeds the theme of labor as a transaction for freedom, a grim mirror to real-world internship cultures and precarious creative work.

- Cultural Appropriation as Gameplay: The “art pieces” are historical masterworks, presented as scrambled tiles. The act of “restoration” is thus framed as a solipsistic puzzle-solving exercise for the player’s benefit, mirroring how museums often treat cultural artifacts as puzzles or aesthetic objects to be solved and displayed for a consuming public, divorced from their original context and meaning. The game sarcastically asks: is authentic restoration possible, or is it just a game of making the image look right?

- The Whimsical Demigod Antagonist: The “whimsical eurasian magpie demigod” responsible for the scrambled art is a brilliant narrative device. Magpies arecollectors; the demigod’s actions makeLiteral the chaotic, acquisitive, and often nonsensical history of museum collections. This figure is not a villain to be fought but a chaotic force whose mischief the player must undo, positioning the player as a cleanup crew for the capricious acts of power.

- Dialogic Irony: The between-puzzle dialogue is the game’s satirical engine. Van Dubenschmitz’s hyper-suave, patronizing commentary likely frames the work as noble, prestigious, or historically vital, creating a stark dissonance with the mechanical reality of swapping tiles to earn imaginary currency. The player’s silence (a common visual novel trope) makes them a receptacle for this absurd rhetoric.

Thematically, the game is a compact criticism of institutional authority, the commodification of culture, and the alienation of labor. It asks whether the “restored” artwork, once reassembled by an underpaid, indebted”restorator,” holds any more authentic meaning than the scrambled version.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Elegance of Constrained Toil

The gameplay is a perfect marriage of form and satirical function. It is a tile-matching puzzle game with first-person, fixed/flip-screen presentation, creating a focused, almost clinical interface.

- Core Loop: The player is shown a historical art piece, thoroughly tiled and shuffled. A sketched outline or partial image serves as a guide. Using a point-and-select interface, the player swaps adjacent tiles to reconstruct the image. This is a classic sliding puzzle mechanic, but with a key constraint: a limited number of “moves.” This transforms it from a casual mind-game into a tense optimization puzzle. Players must parse the composition, plan swaps, and minimize waste—a direct metaphor for the pressure of productive labor.

- The Golden Egg Economy: Hidden within the scrambled grid are golden eggs. Finding one by completing a section or achieving a specific pattern provides a lump-sum payment toward the debt. This introduces a secondary reward loop that encourages exploration and risk-taking within the move limit. The eggs are the game’s “loot boxes,” but instead of cosmetic items, they represent literal liberation.

- Progression & Debt: Progression is linear and inexorably tied to debt reduction. Each successfully restored painting pays a portion of the total. There is no character upgrade system, no skill tree—the only “progression” is numeric debt reduction. This reinforces the game’s themes: you are not becoming a more powerful hero; you are incrementally buying your freedom from a exploitative system.

- UI as a Tool of Control: The minimalist point-and-select interface feels administrative, like using a museum cataloging system. The move counter, the debt meter, the sketched guide—all are cold, numerical metrics thatreduce the sublime art to quantifiable, manageable data. The UI itself becomes part of the satirical commentary on bureaucratic management of culture.

- Innovation & Flaw: Its innovation is in the purity of its metaphorical alignment. The puzzle stress mirrors narrative stress. A potential flaw is the inherent repetitiveness; the satire may wear thin for players not attuned to its theme. However, the game’s brevity (about an hour) is a virtue, ensuring the concept doesn’t outstay its welcome.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetics of Appropriation

The game’s world is the “Bri’ish Museum™” itself, a single, unbroken environment represented by the successive puzzle screens and the dialogue interface. The setting is Europe, but it is a Europe distilled into famous, canonical artworks—presumably from the Renaissance, Baroque, and Romantic periods, given the typical source material for such puzzles. The atmosphere is one of sterile, reverent absurdity.

- Visual Direction: The fixed/flip-screen presentation is key. Each puzzle screen shows the scrambled tiles of a famous painting against a neutral, museum-gray backdrop. The resolution to the scrambled mess is the “proper” canonical image. This visual dichotomy—chaos vs. order, scrambled vs. “original”—is the core visual metaphor. The player’s labor is the process of imposing a singular, authoritative order on a chaotic field. The choice of artworks (likely predominantly Western European masters) implicitly comments on the canon itself.

- Sound Design: The source material provides no explicit details on sound design, which is telling. One can infer a minimalist approach: perhaps subtle, polite ambient museum sounds (distant footsteps, hushed echoes) punctuated by the satisfying click of tile swaps and a triumphant, slightly condescending chime upon puzzle completion or egg discovery. The lack of a dynamic soundtrack keeps the focus on the mechanical action and the dialogue, maintaining the sterile, process-oriented feel.

- Contribution to Experience: Together, these elements create an experience that feels like a satirical simulation of museum curatorial labor. You are not exploring a 3D space; you are performing the intellectual and manual work of “making the collection right.” The aesthetic is not immersive in a traditional sense but is instead diegetically immersive in the bureaucratic process of cultural management.

Reception & Legacy: A Niche Gem with Resonant Critique

Given its recent release and indie, itch.io-exclusive status, Bri’ish Museum Simulator’s reception is understandably niche but surprisingly potent. The available itch.io user reviews (3 ratings, all 5 stars) are ecstatic in their brevity. One user simply states, “I love the gameplay idea, I need more of it (`˵ •̀ ᴗ – ˵ ) ✧”, while another notes, “Very silly and fun little game! That last painting had me quite stumped I must confess.” This highlights the core appeal: a clever, fun puzzle concept wrapped in a hilarious and pointed satirical premise. The “stumped” comment also validates the game’s well-tuned difficulty curve.

Its legacy is currently nascent but can be contextualized within two growing conversations:

1. The “Museum Game” Subgenre: As Vandewalle’s research identifies, games that simulate museum-like collections (from Assassin’s Creed‘s Discovery Tours to Hades‘ Codex) are a recognized form. Bri’ish Museum Simulator joins this field but with a crucial difference: it is not an encyclopedic or educational museum, but a critical one. It simulates the labor and ideology of the museum, not its curated knowledge. It is closer in spirit to a work of institutional critique than to an educational tool.

2. Indie Puzzle-Satire Crossovers: It shares DNA with games that use minimalist mechanics for maximal thematic effect, such as Papers, Please (bureaucratic dystopia) or The Stanley Parable (narrative authority). Its legacy will be as a prime example of how a simple, well-understood gameplay loop (tile-matching) can be recontextualized to deliver a sharp, timely social commentary without a single cutscene or vast budget.

Its influence on the broader industry is yet to be seen, but it serves as a potent reminder that conceptual clarity and thematic integration can outweigh graphical fidelity or scope. It proves that the “museum simulator” can be a vessel for critique, not just celebration.

Conclusion: A Definitive Verdict on a Modern Satirical Artefact

Bri’ish Museum Simulator is not a game about art; it is a game about the politics of art ownership and the liturgy of labor. In under an hour, using a puzzle mechanic sourced from a 1999 Microsoft classic, it delivers a more coherent and damning critique of museological practice than many sprawling historical epics. Its genius lies in the absolute alignment of its mechanics with its message: the player feels the grind of debt repayment, the tension of move limits, and the hollow victory of “restoring” a canonical image they had no hand in creating or contextualizing.

Its place in video game history is secure as a perfectly realized indie satire. It demonstrates that the most effective institutional critiques can be embedded in the gameplay itself, not just the writing. It joins the vanguard of games that use their interactive nature to make players complicit in the systems they portray. For scholars, it is a vital case study in “game-based learning” not for historical facts, but for critical theory. For players, it is a short, hilarious, and intellectually bracing experience that will linger in the mind far longer than its runtime suggests.

In the end, the “Bri’ish Museum” is not a place of wonder but a workshop of penance. And Bri’ish Museum Simulator is the unforgettable, tile-swapping receipt for that truth. It is a must-play for anyone interested in the evolving grammar of interactive satire and the untapped potential of the puzzle genre as a space for critical discourse.