- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

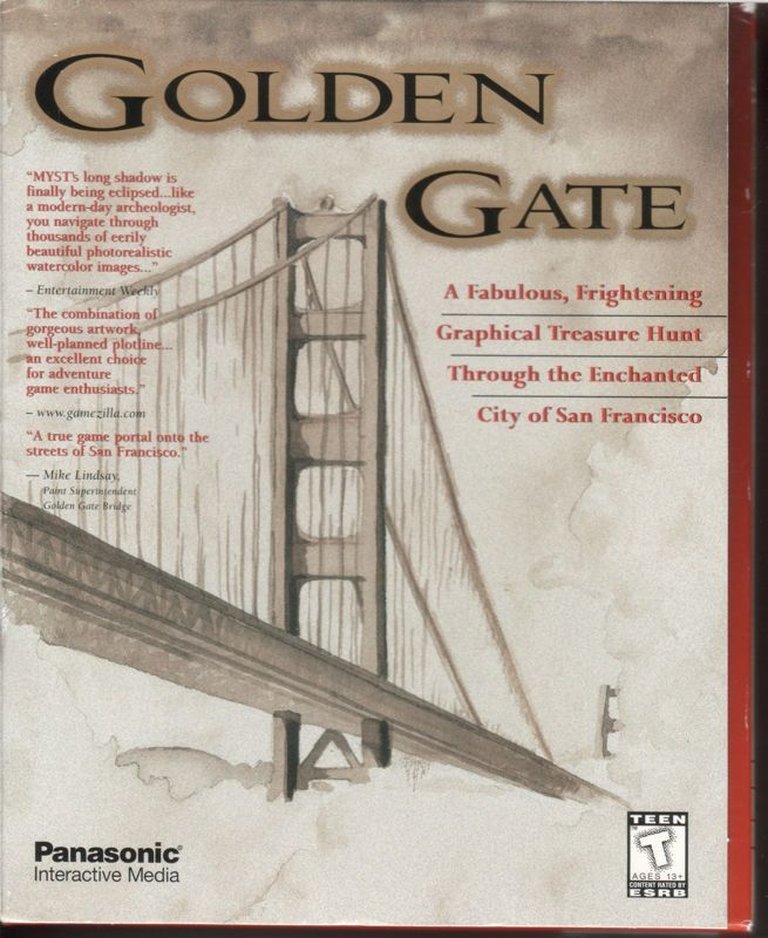

- Publisher: Panasonic Interactive Media

- Developer: iX Entertainment

- Genre: Adventure, Educational

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Inventory-based, Point-and-click, Puzzle, Treasure Hunt

- Setting: North America, San Francisco

Description

Golden Gate is a first-person point-and-click adventure game set in modern-day San Francisco, where players embark on a treasure hunt to uncover an ancient hidden treasure based on historical legends. Featuring hand-painted watercolor scenes of iconic locations like Lombard Street and Chinatown, players solve puzzles and examine documents such as diaries and letters to piece together clues, with full-motion video cutscenes advancing the narrative.

Gameplay Videos

Golden Gate Patches & Updates

Golden Gate Guides & Walkthroughs

Golden Gate Reviews & Reception

balmoralsoftware.com : Probably the best feature of Golden Gate is its enjoyable acoustic soundtrack.

oldpcgaming.net : In the end, Golden Gate is a merely average Myst-style adventure clone, and that’s if you’re feeling rather generous.

collectionchamber.blogspot.com : It’s a bit of a hidden relic – quiet, strange, and disarmingly beautiful.

Golden Gate: A Watercolor Mirage of San Francisco – An Exhaustive Historical Review

1. Introduction: The Allure of a Painted City

In the mid-1990s, the adventure game genre was dominated by the seismic shadow of Myst and its countless “slide-show” imitators. Into this crowded field stepped Golden Gate, a 1997 title from the modest studio iX Entertainment and published by the electronics giant Panasonic Interactive Media. Marketed as a “time-spanning, graphical treasure hunt,” it promised not just a puzzle-solving journey but an immersive, artistic love letter to San Francisco. Its central, ambitious proposition was breathtaking: to replace the fantastical, alien landscapes of Myst with the meticulously rendered, familiar architecture of a real-world metropolis, all rendered in a distinctive watercolor aesthetic. This review argues that Golden Gate is a fascinating, deeply flawed historical artifact—a game whose visionary artistic direction and genuine affection for its setting are perpetually at war with clunky technology, thin gameplay, and a fundamentally unsatisfying narrative resolution. It stands as a poignant case study in ambition exceeding execution, a beautiful postcard whose message is frustratingly incomplete.

2. Development History & Context: The Panasonic Experiment

The Studio and Vision: iX Entertainment was a small American development house, known more for contract work than original IPs. Producer Vince Zampella (later a co-founder of Infinity Ward and Respawn Entertainment) and producer/artist Alex Kazim helmed the project. The team’s vision, as stated in promotional material and reinforced by the game’s meticulous credits, was one of “authentic historical research and San Francisco legends.” They aimed to blend a detective/mystery narrative with an educational tour of the city’s landmarks, from Lombard Street and Chinatown to the decks of the Balclutha and the trails of Angel Island. Panasonic Interactive Media, seeking to leverage its brand and CD-ROM technology, provided the publishing muscle and likely the budgetary constraints that defined the game’s scope.

* Technological Constraints & The CD-ROM Era:* Released in April 1997 for Windows and Macintosh, Golden Gate was a product of the CD-ROM’s golden age. The game installs a minimal executable to the hard drive but streams the vast majority of its assets—over 2,000 hand-painted 16-bit watercolor images and full-motion video (FMV) sequences—directly from the CD. This technological choice explains its infamous performance issues. As the player review from MobyGames and the Balmoral Software walkthrough attest, the game suffered from “long scene load times, bad transitions and many crashes” on contemporary hardware like a Pentium 100. The slideshow format, where scenes are static images with interactive “hot spots,” was a direct result of this streaming limitation, intended to mask load times but creating a disjointed, non-dynamic world. A 3DO Interactive Multiplayer version was in development but was ultimately cancelled, a footnote that hints at the platform’s decline and the project’s uncertain commercial prospects.

The Gaming Landscape: Golden Gate arrived in a post-Myst (1993), post-The 7th Guest (1993) world. The “Myst-clone” was a dominant subgenre, characterized by first-person exploration, static pre-rendered backgrounds, and inventory-based puzzles. Golden Gate attempted to differentiate itself through its verisimilitude—using a real city—and its unique art style. It competed with titles like Shivers (1995) and the forthcoming Riven (1997), which pushed graphical fidelity. Where Golden Gate diverged was in its tone: it was less horror, more historical mystery; less isolation, more a tourist’s reverie. However, as Adrenaline Vault bluntly stated, it offered “a very good implementation of a very small idea,” failing to meaningfully evolve the mechanics it borrowed.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Century of Secrets and Madness

Plot Deconstruction: The narrative, credited to Jorge Martin De Nicolas, is a multi-generational pulp mystery told through scattered documents and flashback FMV sequences. It begins in 1906 with a letter from a descendant of a grain trader, referencing a “necklace” and a “truth of the past.” The player, a modern-day treasure hunter, must follow this trail. The backstory, pieced together from diaries (like Alexandra’s), letters, and mission records, reveals a convoluted saga:

- The Caledonian Origin: An “ancient treasure” is linked to King William of Caledon, a fictional Scottish monarch whose kingdom was plagued by “an evil beast.” The beast’s spirit was trapped in a tree, made into a chest, and entrusted to the royal family.

- The New World Flight: Centuries later, King William flees to colonial California after his kingdom falls. His daughter, carrying the treasure’s keys (three gemstones: emerald, ruby, sapphire) and a figurehead with gemstone eyes (“Esperance”), is pursued by an evil pirate named Drussard.

- San Francisco Scattering: In the nascent San Francisco, a battle occurs. Alexandra (the daughter) scatters the three gemstones and three corresponding keys (symbolized as a hand, leaf, and claw) across the city. She perishes, her diary the first major clue.

- The 1906 Cycle: A boy finds a bottle containing notes and a key. His father, driven by the “Beast” (a metaphor for obsession/madness), goes mad and dies on Angel Island. His notes become part of the cycle.

- The Wartime Interlude: In 1941, on the eve of WWII, Drussard (now an old man) is on Angel Island. A doctor, Holden, becomes entangled, leading to a gruesome murder and the hiding of a final “leaf key” at Wallace Battery.

- The Modern Pursuit: The player, a new seeker, enters. A rival, the “sloppy derelict” Jake T. Matthews, appears via FMV, ostensibly as a competitor but ultimately as a narrative dead end.

Themes: The game explicitly themes itself around:

* History as Palimpsest: San Francisco is a literal and metaphorical palimpsest. Layers of history—Native, Spanish, Gold Rush, 1906 Quake, WWII—are physically and文档ually buried. The gameplay mechanic of “reading other people’s diaries, letters or manuscripts” reinforces this.

* Obsession and Madness: The “Beast” is the personification of greed and historical obsession. Every prior seeker (the grain trader’s descendant, Alexandra’s father, Jake) is consumed by it. The game’s “Beast” mechanic—being “taken over” if gemstones are placed incorrectly in the final box, resulting in a bizarre color palette shift—is a literalization of this theme, though poorly integrated.

* San Francisco as Character: The city is not just a backdrop but the central puzzle board. Every landmark has a narrative function: Lombard Street’s plaques (SCIENCE, ART, LETTERS) hint at puzzle solutions; Fort Point’s brochure explains a bell code; the Balclutha telescope reveals geographic clues. The city’s geography is the game’s logic circuit.

Critique: While ambitiously layered, the narrative is disjointed and frustratingly opaque. Critical reviews from Quandary and Just Adventure note “too much written material… far too disjointed to make a whole lot of coherent sense.” The connections between King William’s mythical beast and the 1906 earthquake, or between Drussard’s piracy and the Vigilance Committee, are tenuous at best. The FMV sequences, particularly those featuring Jake, are singled out for “terrible” acting and poor integration with the watercolor graphics, creating a jarring tonal clash. The player review on MobyGames succinctly captures the failure: “His speech and the videos in which he appeared were terrible… I would have rather been left totally alone.” The ending, where the treasure is revealed as a simple map and a message from King William, is universally condemned as anticlimactic. As the Balmoral walkthrough notes, the “disappointing endgame sequence” justifies the effort invested only for the most dedicated.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Non-Linear Quagmire

Core Loop: Golden Gate employs a first-person, point-and-click slideshow interface. The player navigates a network of “position nodes”—static 360° panoramas of San Francisco locations. Movement is controlled via a directional “rosette” cursor (evaluated positively by Balmoral for its clarity and keyboard compatibility). The primary tools are observation (panning 360°, zooming on details), inventory collection, and environmental puzzle-solving.

Puzzle Design: The game contains a sparse set of puzzles, estimated at 9-10 major ones, scattered across the city. They include:

* The Balclutha Ship Wheel: A concentric-ring puzzle requiring rotation to match a map seen earlier. Simple logic.

* Old Mint Magic Square: A classic 3×3 magic square (using digits 1-9). The Balmoral walkthrough provides the unique solution: 4 9 2 / 3 5 7 / 8 1 6. This is the game’s most famous and well-regarded puzzle.

* Vigilance Committee Bell Code: Requires recalling a sequence from a brochure (Middle, Down, Down, Middle).

* Cliff House Jukebox: A three-tumbler lock set to the Horus hawk symbol seen on Lombard Street plaques.

* Pacific Heights Jack-in-the-Box: A complex musical puzzle requiring the correct sequence of 7 tone sliders to play “Pop Goes the Weasel,” with 823,543 possible combinations. The provided solution is Up 2, Up 6, Up 4, No Change, Up 3, Up 5, Up 1.

* Mission Dolores Tomb Anagram: Rearranging “FOLLOW IDLE MANIAC” into “WILLIAM OF CALEDON” and correcting the death year to 1789.

* Point Knox Lighthouse Mosaic: A complex 3×3 grid puzzle where pressing squares affects others in a dependent sequence. The Balmoral walkthrough details a 70-click solution sequence (I:2, C:7, G:4, etc.).

* Angel Island Key Retrieval & Box Assembly: Gathering the three keys (hand, leaf, claw) and inserting them with the three gemstones into the final box in the correct order.

Strengths & Fatal Flaws:

* Non-Linear Exploration: The San Francisco map allows instant travel to visited nodes, a significant quality-of-life feature praised by players. The game is “fairly open and non-linear.”

* Puzzle Logic: Most puzzles are logically consistent with the in-game documents. The magic square and anagram are classic, fair puzzles. The jack-in-the-box and mosaic puzzles, while complex, have in-game clues.

* The “Search” Problem: The major failing is clue acquisition. As the player review states, “you may find yourself wandering around clueless until you get lucky.” Vital clues (like the Fort Point bell code brochure or the Lombard Street plaques) are easily missed if the player doesn’t thoroughly inspect every zoomable detail in every location. This transforms puzzle-solving into a frustrating pixel-hunt within a beautiful, empty city.

* Roadblock Design: Several puzzles, notably the Point Knox mosaic, are essentially brute-force barriers without the walkthrough. Their solutions are not hinted at sufficiently in-game, making them feel like arbitrary “roadblocks (or to lengthen gameplay time)” as the MobyGames review notes.

* Interface Quirks: The cursor “is quirky and unnecessarily complex… Sometimes when you clicked to go one direction you’d end up somewhere else.” The map, while useful, is not flawless. These control issues break immersion.

* Lack of Reset: “Most of the puzzles have no ‘reset’ capability,” forcing reloads upon incorrect experimentation, a significant frustration for the mosaic puzzle.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: The Mirage in Focus

Visual Artistry – The Watercolor Revolution: This is Golden Gate’s undisputed masterpiece and primary legacy. The development team, led by Art Directors John Kitses and Tony Welch, employed a painstaking process: photographing real San Francisco locations, then painting over them with a watercolor filter in software like Photoshop. The result is over 2,000 hand-painted, 16-bit images that capture the city’s iconic topography—the fog-draped hills, the pastel Victorians, the stark industrial piers—with a dreamy, impressionistic quality. As Coming Soon Magazine prophetically noted, this “visual look and sound… set it apart. One that surely deserves imitation.” The 360° panoramas, while static, create a potent sense of place. The review from MobyGames captures the paradox: “The scenery looks realistic (albeit a bit out of focus)… you feel as though you are actually somewhere.” However, this beauty is inherently static and lifeless. As Adrenaline Vault criticizes, it is “just still photos with ‘hot spots’… Nothing really moves as it should.” The city is a museum exhibit, not a living world. The FMV cutscenes, featuring the live-action Jake and historical flashbacks, are of notably lower, grainier quality, creating a jarring aesthetic mismatch that Old PC Gaming describes as a “strange… stretch of the imagination.”

Sound Design & Music: The soundtrack, composed by an uncredited team, is widely praised as the game’s other pillar. Described as “enjoyable acoustic” (Balmoral) and “nicely added to the feel of each scene,” it features moody, ambient tracks that adapt to locations. The inclusion of a “jukebox feature” to listen to the score outside the game is a rare, appreciated touch. Sound effects (crashing waves, seagulls) provide vital atmospheric context for the static images. However, technical issues marred the experience: the MobyGames user review notes the music “nicely added to the feel of each scene (when it didn’t stutter).” These performance stutters were a common symptom of CD-ROM streaming.

World-Building Through Environment: The accolades for authenticity are well-founded. The game’s “educational” tag is earned through its accurate (if selective) depiction of locations: the Hyde Street Pier and the Balclutha, the Mechanics Museum at the Cliff House, the ruins of the Old Mint, Mission Dolores. The use of real San Francisco legends (the Vigilance Committee bell code) and historical touchstones (the 1906 earthquake, WWII) grounds the fantastical plot in a plausible reality. This creates a powerful, if melancholic, sense of a city emptied of contemporary life. As the player review observes, “the current inhabitants of the city appear to be limited to Jake T. Matthews, a competing treasure hunter.” San Francisco becomes a haunted, living museum, populated only by ghosts of the past via documents and FMV, a concept both eerie and isolating.

6. Reception & Legacy: A Diamond in the Rough, Polished to No Avail

Critical Reception at Launch: The game’s Metacritic-like aggregate (58% from 11 critics) masks extreme polarization. Reviews ranged from the rapturous (Gamezilla: 89%, Coming Soon Magazine: 85%) to the vitriolic (Game Revolution: 16%, Quandary: 40%). The schism centered on the trade-off between artistry and gameplay.

* The Positives: Critics like CD Mag (which called it “a diamond in the rough”) and Four Fat Chicks celebrated its “classy,” “old-fashioned” style and “great music.” They were swayed by the historical research and the unparalleled virtual tour of San Francisco. Coming Soon Magazine predicted its visual style “would be copied by other games.”

* The Negatives: Game Revolution dismissed it outright for Myst and S.P.Q.R. fans. The Adrenaline Vault delivered the most succinct critique: “the interface and technical implementation is wonderful, but there isn’t a lot of meat underneath the wrapper.” Electric Playground found the gameplay “standard, uninspired and slow.” Mac Gamer and Quandary felt the narrative was weak and the ending pointless. The majority consensus was that it was a beautiful, slow, and ultimately hollow experience.

Player Reception & Longevity: Player scores (3.3/5 on MobyGames from 8 votes) are similarly mixed. The lone extensive player review (Jeanne’s) perfectly encapsulates the ambivalent player experience: appreciation for the virtual tourism and challenging puzzles, balanced against frustration with the bugs, the terrible NPC Jake, and the disappointing ending. The fact that Jeanne only finished because she was writing a hint file is a devastating indictment. The game has a small, dedicated cult following—evidenced by the existence of detailed walkthroughs and patch files on sites like Balmoral Software and The Patches Scrolls. Its “collected by” number on MobyGames (16 players) is tiny, confirming its niche status.

Legacy and Influence: Golden Gate‘s direct influence on the industry is minimal. It was not a commercial blockbuster, and its specific watercolor technique was not widely adopted. Its legacy is more conceptual and nostalgic. It stands as:

1. A High-Water Mark for Location-Based Adventure Games: It was arguably the most ambitious attempt to use a real, modern city as the core puzzle space in a graphical adventure. Later games like The Journeyman Project or Amerzone used exotic locales, but few attempted the dense, familiar geography of a major U.S. city.

2. A Cul-de-Sac in the “Myst-clone” Genre: It demonstrated the limitations of the slideshow format when applied to a bustling urban environment. The inherent stillness became a liability, not a virtue, when depicting a city known for its fog, cable cars, and bustling life. The genre evolved toward 3D real-time engines (like Grim Fandango‘s pre-rendered scenes with character sprites, or eventually fully 3D worlds), leaving the static panorama behind.

3. A Precursor to “Edutainment” and Virtual Tourism: Its blending of historical fact (however loosely) with game exploration prefigured later “cultural heritage” games and serious games. In an era before Google Earth, it offered a form of armchair travel that was artistically unique, even if gameplay-poor.

4. A Curio of Mid-90s CD-ROM Excess: It embodies the era’s “too much asset, too little design” problem—thousands of beautiful images in service of a skeletal, buggy game. It is frequently cited in discussions of “Myst clones” as a prime example of style overwhelming substance.

7. Conclusion: The Treasure Remains Buried

Golden Gate is not a lost classic. It is not a game that time has been unkind to; it was a problematic product from the start. Its MobyScore of 6.3 and its polarized reviews are accurate reflections of a title that is strikingly beautiful yet fundamentally broken. The watercolor panoramas of San Francisco remain a stunning technical and artistic achievement for 1997, offering a unique, painterly vision of the city that no other game has replicated. The soundtrack is superb. The concept of weaving a multi-generational mystery into the literal geography of the city is brilliant.

However, these strengths are buried under a mountain of flaws: a disjointed, unsatisfying story; a sparsely populated world with a single annoying NPC; performance issues that plagued the CD-ROM era; puzzles that devolve into frustrating, under-clued hunts; and an ending that nullifies the entire journey. The gameplay loop is less “engrossing treasure hunt” and more “tedious, beautiful pixel-hunt.”

Its place in history is as a noble failure—a cautionary tale about the perils of prioritizing artistic vision and historical research over robust gameplay design and narrative coherence. It is a game to be studied, not played. For historians, it is a fascinating data point: a major electronics manufacturer’s bold adventure into software, a studio’s labor of love, and a genre’s evolutionary dead end. For the modern player, it is a beautiful mirage—best appreciated through screenshots, its soundtrack, and its detailed walkthroughs, rather than through the laborious, crash-prone experience of navigating its silent, watercolor streets in search of a treasure that, in the end, feels profoundly hollow. The “truth of the past” it promises remains, like the game itself, obscured by the fog of its own ambition.