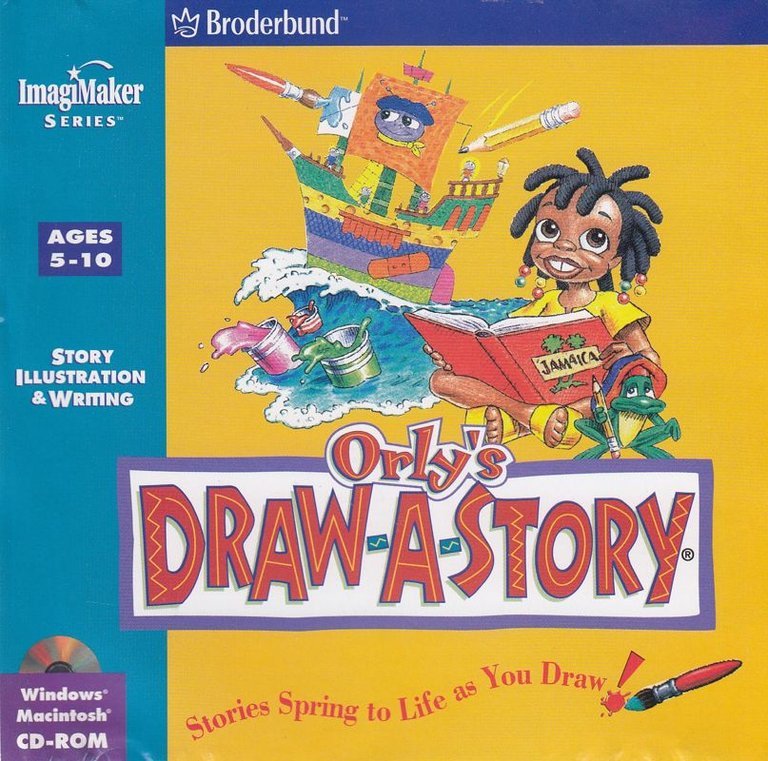

- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows 16-bit, Windows

- Publisher: Brøderbund Software, Inc.

- Developer: ToeJam & Earl Productions, Inc.

- Genre: Educational

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Drawing, Interactive book, Story creation

Description

Orly’s Draw-A-Story is an educational game released in 1997 that teaches children to draw through interactive storytelling. Narrated by Orly, a young Jamaican girl, and her talking frog sidekick Lancelot, the game features four animated stories where players pause to draw characters or props using basic tools like pencils and paints. These drawings are incorporated into the narrative, and the game also includes a storybook maker for creating new tales and a doodle pad for free drawing, fostering creativity and artistic expression in a culturally rich setting.

Gameplay Videos

Orly’s Draw-A-Story Free Download

Orly’s Draw-A-Story Reviews & Reception

metron.com : This game pulled out all the stops – the design team labored with love.

Orly’s Draw-A-Story: Review – A Cult Classic of Creative Empowerment

Introduction: The Ghost in the Machine of Childhood Creativity

In the crowded pantheon of 1990s educational software, where alphabet drills and math flash cards dominated retail shelves, Orly’s Draw-A-Story emerged as a quiet, radical anomaly. Released in 1997 by Broderbund and developed by the idiosyncratic ToeJam & Earl Productions, this CD-ROM title presented a deceptively simple proposition: what if a video game didn’t teach you to answer correctly, but instead gave you the tools to create your own world? It was a game that understood a fundamental truth about childhood imagination—that the magic lies not in consumption, but in authorship. For a generation of players, Orly’s Draw-A-Story was more than software; it was a portal. It was the game that haunted their minds, as one Reddit user perfectly phrased it, until they finally rediscovered its name decades later. This review argues that Orly’s Draw-A-Story is a landmark of interactive design, a poignant case study in critical acclaim versus commercial success, and a direct precursor to the user-generated content ecosystems that define modern gaming. Its legacy is not in units sold, but in the millions of personal stories it quietly sparked.

Development History & Context: From Space Hamsters to Jamaican Jungles

To understand Orly’s Draw-A-Story, one must first understand its developer: ToeJam & Earl Productions (TJ&E). Founded by Mark Voorsanger and Greg Johnson, the studio was an industry curiosity. Their claim to fame was the cult-classic Sega Genesis games ToeJam & Earl (1991) and ToeJam & Earl in Panic on Funkotron (1993)—absurdist, improvised comedies about alien rappers lost on Earth. Their style was chaotic, humorous, and deeply personality-driven. With Orly’s, they pivoted entirely, applying that same creative, character-first ethos to a children’s creativity tool. As the MobyGames credits reveal, the core team of Voorsanger (Programming/Project Management), Johnson (Conceptual Design/Writing/Production), and Kirk Henderson (Art & Animation Direction) were all deeply involved, with Henderson noting “Nothin’ like a good movie soundtrack,” hinting at the cinematic ambitions of the project.

The game was built using the Mohawk game engine, a toolkit from Macromedia (formerly MacroMind) common in mid-90s interactive titles. This placed Orly’s firmly in the CD-ROM “multimedia” era, a time of lavish (for the period) full-motion video, voice acting, and ambitious graphics. The technological constraint was balancing rich animation and sound with the limited drawing tools. The solution was brilliant: the player’s crude drawings were “frozen” in a simple, clean style, but the game’s engine seamlessly animated them within the pre-rendered story sequences. This created a magical dissonance where a child’s wobbly monster would hop through a lush, professionally animated Jamaican landscape.

Broderbund, the publisher, was a titan of the edutainment genre (The Oregon Trail, Carmen Sandiego). Their involvement guaranteed distribution in school catalogs and family software aisles, but also likely came with expectations of clear educational ROI. Orly’s subverted this by making “education” indistinguishable from pure, unadulterated play. The game’s setting—a vibrant, sun-drenched Jamaica—was a deliberate, bold choice. The credits explicitly list Alreca Whyte as both the voice of Orly and the “Jamaica Advisor,” ensuring cultural specificity beyond superficial aesthetic. The reggae-infused soundtrack, composed by Burke Trieschmann, was not just background noise but an integral atmospheric character, as noted in contemporary reviews.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Orly’s World and the Architecture of Imagination

At its heart, Orly’s Draw-A-Story is about agency. The narrative framework is a series of four standalone tales, each a mini-parable of problem-solving through creativity. The protagonist, Orly, is an eight-year-old girl with an infectious, encouraging personality (voiced with genuine warmth by Alreca Whyte). Her companion, Lancelot the frog, provides comic relief and literal “frog’s-eye” commentary. Their dynamic is not a teacher-student relationship, but a peer-to-peer collaboration. Orly doesn’t judge; she offers feedback like “That’s a nice color” or the famously cheeky “It’s so ugly I can hardly believe it,” which, as the SuperKids review highlighted, is part of its charm.

A thematic analysis of the four stories reveals a consistent architecture:

- “The Ugly Troll People”: This story directly confronts the theme of perception and inner worth. The “ugly” trolls are ostracized, and the player must draw them a beautiful, magical friend. The act of creation is an act of redefinition and inclusion.

- “The Strange Princess”: Here, the theme is empathy and understanding. The princess behaves “strangely,” and the player must draw objects that help her feel better or communicate. It’s a gentle lesson in non-verbal emotional support.

- “Lancelot, Bug Eater”: A tale of overcoming personal flaws and societal expectation. Lancelot’s appetite is a source of shame until the player draws a solution (a “Bug Buffet” or similar), transforming a weakness into a celebrated trait.

- “One Big Wish”: This is the pure power-of-desire narrative. Orly makes a grand wish, and the player must draw the fantastical object to fulfill it, culminating in a sequence of pure, wish-fulfillment joy.

The genius lies in the integration. The player isn’t just illustrating a static story; they are writing a critical chapter in real-time. The drawing prompt is always a narrative necessity: “We need a friend for the lonely monster.” The completed drawing doesn’t just appear; it is activated. As MobyGames describes, “Once the drawing is complete, it becomes incorporated into the story as it continues.” This moment of animation—your scribbled monster hopping across the screen—is the game’s core feedback loop, a powerful dopamine hit that validates the child’s creative labor.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Drawing Board as Command Console

Orly’s Draw-A-Story operates on a deceptively simple point-and-select interface. The screen is divided into the main story animation area and a persistent drawing palette. The core gameplay loop is:

- Narrative Beat: Orly and Lancelot advance the story via voiceover and animation.

- Prompt & Pause: The narrative halts. Orly states the need (“I need a birthday present!”).

- Creation Phase: The player enters the drawing pad. Here, the system offers two key innovations:

- The “Shutter” Template System: A clickable button opens a window with dozens of pre-drawn line art templates (classified as “Orly & Lancelot,” “Creatures & Plants,” “People,” “Other Things”). A child can select one, color it with a palette of 32 colors, and modify it with basic tools (pencil, paint bucket, eraser). This lowers the barrier to entry immensely, preventing frustration.

- Freeform Drawing: The player can start from a blank canvas, using the same tools. The system includes “weird textures like goop and eyeballs” (as the Metron review notes), adding tactile, playful depth.

- Integration & Continuation: The finished drawing is saved, the shutter closes, and the story resumes, now starring the player’s creation. The characters often comment on the drawing.

- Conclusion & Gallery: After the story, the player can save the illustrated page to a personal gallery or discard it.

This loop is repeated 4-5 times per story. The “Make A Storybook” mode is the game’s true systemic masterpiece. It provides a blank slate: select backgrounds (from 20 scenes), place multiple drawn or template characters, record or type dialogue (using a simple text-to-speech or just displaying text), and add sound effects (from a library of 20). This is a complete, if rudimentary, filmstrip creator. It transfers the game’s core mechanic—”your drawing drives the narrative”—into a sandbox with no limits. The “Doodle Pad” is a pure, unguided practice space.

There are no scores, no failure states, no timers. The only “progression” is the accumulation of saved storybook pages and the player’s growing confidence. The UI is deliberately simple, with large, friendly icons. The only minor flaw, noted anecdotally on MyAbandonware, is the archaic Windows 3.x/95-era drivers causing audio glitches on modern systems, a technical artifact, not a design flaw.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Synesthesia of Jamaican Storytelling

The world of Orly’s Draw-A-Story is its most enduring and celebrated aspect. It is a pastel-drenched, sun-bleached vision of Jamaica, realized in the limited 2D sprite and background art of the era. The environments are lush (jungles, beaches, cloud kingdoms) but simplified, providing a non-distracting stage for the player’s vibrant, often chaotic, additions. This artistic contrast is key: the game’s world is a stable, beautiful canvas upon which the player’s dynamic, personal imagination is projected.

The character design is iconic. Orly, with her braids and bright clothes, is an instantly memorable, racially specific protagonist—a rarity then and now. Lancelot is a classic cartoon frog, expressive and bouncy. The template creatures span the fantastical (flying monsters, trolls) to the mundane (trees, chairs), giving players a rich vocabulary.

But the soul of the world is sound. Burke Trieschmann’s soundtrack is a masterclass in diegetic audio. The pervasive, soothing reggae rhythm (steel drums, off-beat guitar) doesn’t just set a Caribbean mood; it creates a psychological safe space for creativity. It’s music that says, “Relax. Experiment. Nothing is wrong here.” The sound effects are similarly playful and punctuated—a “boing” when a character jumps, a “splash” when something appears, a whimsical chime for success. The SuperKids review’s anecdote about drawing a yellow submarine and hearing a reggae version of “Yellow Submarine” is not an isolated example; the game is filled with these delightful, culturally-aware musical Easter eggs that reward engagement. This synergy of visual simplicity and rich audio creates a complete sensory experience that is both specific (Jamaican) and universal (joyful).

Reception & Legacy: The Acclaimed Enigma

Upon its 1997 release, Orly’s Draw-A-Story was met with near-universal critical praise, a fact underscored by its 88% average score on MobyGames from critics like AllGame (90%) and SuperKids (87%). The Atlanta Constitution awarded it a rare A+. The accolades were not limited to gaming press; prestigious mainstream publications like Computer Life and Newsweek covered it favorably. Its pinnacle of recognition was winning the 1998 Interactive Achievement Award (now D.I.C.E. Awards) for “PC Creativity Title of the Year,” beating industry heavyweights like Disney’s Magic Artist and Barbie Cool Looks Fashion Designer. This award, from the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences, was a monumental validation of its innovative design.

Yet, despite this critical tsunami, the game was not a commercial success. As Wikipedia and multiple sources state plainly, it “was not a market success.” The reasons are speculative but logical: it was a CD-ROM in a rapidly transitioning 3D-accelerated PC gaming market. Its educational branding may have pigeonholed it, preventing it from reaching the broader “creative software” audience (like CorelDRAW or Adobe Photoshop users). Its niche subject matter and lack of explosive marketing compared to a Disney title meant it faded from shelves quickly.

Its legacy, however, is profound and evolving:

- Influence on Game Design: It predated and arguably influenced the wave of “drawing-based” games that followed, from Draw a Stickman (2011) to Drawn to Life. The core mechanic of “player drawing becomes game asset” is now a standard trope.

- The Sandbox Storytelling Precursor: Its “Make A Storybook” mode is a direct ancestor to modern level editors (LittleBigPlanet, Super Mario Maker) and video creation tools in games like Minecraft or Roblox. It validated the concept of the player as narrative author.

- Cult Rediscovery: Decades later, it has been lovingly preserved and sought after by a dedicated retro community, as evidenced by the passionate, troubleshooting-filled comment threads on MyAbandonware and Reddit’s r/nastalgia. Users share localization stories (its massive popularity in Brazil as Orly Desenhando Histórias), struggle with emulation (running it via Windows 3.1 in DOSBox), and trade user guides. This is the hallmarks of a cult classic—a work that failed broadly but connected deeply with individuals.

- Educational Reassessment: Its 2001 repackaging by The Learning Company for school use cemented its pedagogical value, even if the original vision was more about creativity than curriculum.

Conclusion: Verdict and Historical Placement

Orly’s Draw-A-Story is a flawless gem of a concept executed with poignant, heartfelt simplicity. It is not a “game” in the conventional sense of challenge and victory, but an interactive creative instrument. Its mechanics are elegant, its world is warm and specific, and its core loop of “draw, see it live” remains powerfully effective. The disconnect between its stellar critical reception and its market failure is less a judgment on the game and more a commentary on the commercial realities of its time—a truly innovative experience can be crushed by category, timing, or distribution.

In the grand timeline of video game history, Orly’s Draw-A-Story belongs in the chapter on “Expanding the Medium’s Purpose.” It stands shoulder-to-shoulder with Myst (1993) in proving games could be about exploration and experience, not just action. It preceded SimCity‘s educational ethos in a different domain. It was a quiet rebellion against the “edutainment” trend of making learning palatable by dressing it up as a game; instead, it made creating the game itself, and in doing so, made learning an unconscious byproduct.

For the historian, it is a case study in auteur-driven design from a studio known for comedy, showing the breadth of their creative range. For the preservationist, it is a title worth saving for its unique cultural snapshot—a 90s American attempt at a positive,Specific Caribbean-inspired narrative for children. For the player, it remains a hauntingly beautiful memory of empowerment, the game that first whispered, “You can be the storyteller.”

Final Verdict: 9.5/10 – A visionary, ahead-of-its-time masterpiece whose minor technical limitations are utterly overshadowed by its profound, player-centric design. Its commercial obscurity is a historical footnote; its influence on creative play is an enduring legacy. It is not merely a children’s game; it is a foundational text on the democratization of authorship in interactive media.