- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Avanquest Software Publishing Ltd.

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Setting: Ancient

Description

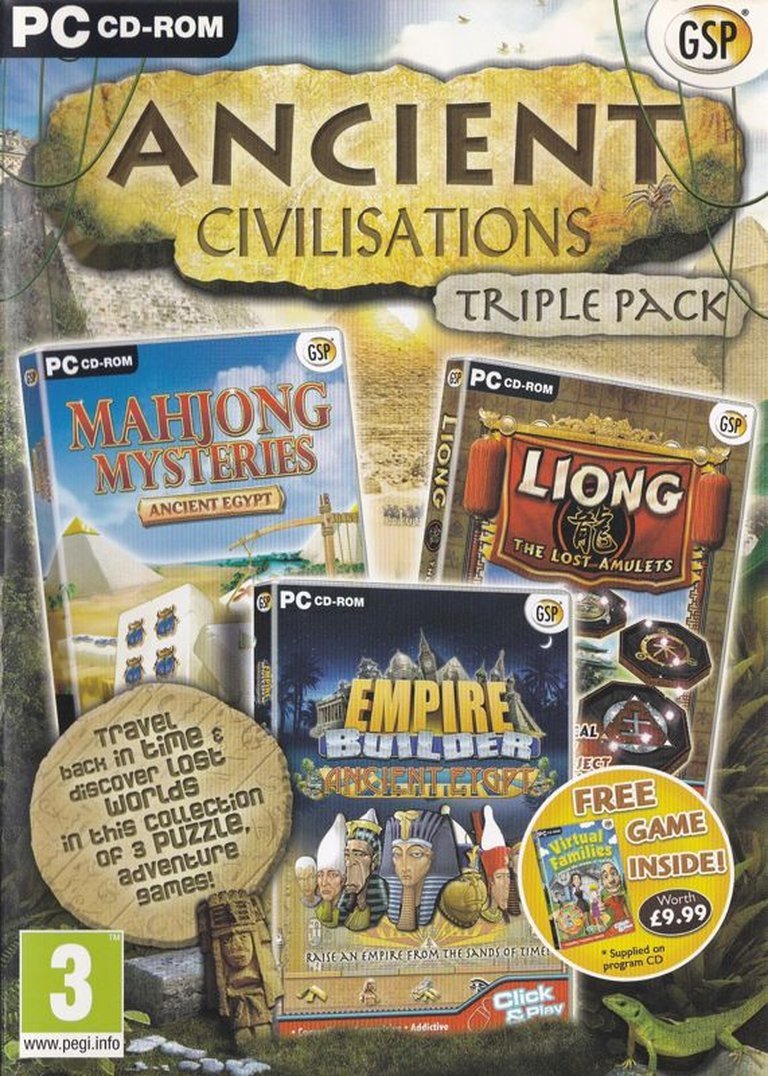

Ancient Civilisations: Triple Pack is a 2010 Windows compilation that bundles three games—Empire Builder: Ancient Egypt, Liong: The Lost Amulets, and Mahjongg Mysteries: Ancient Egypt—each set in ancient civilizations like Egypt, along with the bonus game Virtual Families. All four titles are installed separately from a single DVD, offering diverse gameplay experiences from empire-building and puzzle-solving to simulation, all centered on historical or mythical ancient settings.

Ancient Civilisations: Triple Pack Free Download

Ancient Civilisations: Triple Pack: Review

Introduction: A Time Capsule of Casual Gaming’s Bargain Bin

In the sprawling ecosystem of video game history, certain artifacts serve less as monumental titans and more as fascinating cultural artifacts—products of their time that reveal the commercial and design philosophies of an era. Ancient Civilisations: Triple Pack (2010) is precisely such an artifact. Released for Windows at the twilight of the DVD-ROM’s dominance and the peak of the casual PC gaming boom, this compilation is not a cohesive artistic statement but a commercial anthology. It bundles four distinct games—three ostensibly thematically linked by a vague “ancient” setting, plus a fourth as a curious “bonus”—onto a single disc, targeting the budget-conscious and time-pressed shopper. This review will argue that the Triple Pack’s historical significance lies not in its individual components, which are textbook examples of low-friction, genre-template gaming, but in its embodiment of a specific market strategy: the value-driven, thematically loose compilation that saturated retail shelves in the late 2000s. It is a document of convenience, a snapshot of the casual puzzle and light-simulation genres at a moment of formulaic refinement, and a testament to the era’s packaging-driven sales.

Development History & Context: The World of GSP and Avanquest

The Studios and the Vision (or Lack Thereof)

The “vision” behind Ancient Civilisations: Triple Pack is not that of a single creative team but of a business strategy. The credited publisher is Avanquest Software Publishing Ltd., a European company with a long history of distributing budget-friendly software, utilities, and games, often through mass-market retailers. The games themselves are clearly contracted out. The source material reveals a patchwork of development origins:

* Empire Builder: Ancient Egypt (2009) and Liong: The Lost Amulets (2009) are attributed to unspecified developers under the Avanquest/GSP umbrella.

* Mahjongg Mysteries: Ancient Egypt (2010) and Virtual Families (2009) come from different studios (Merscom Games, Cerasus Media, eGames, per the Internet Archive copyright notice).

There was no unified creative directive. The “ancient civilisations” theme is a post-hoc marketing skin applied to a collection of disparate games found in Avanquest’s licensing library that fit a vague historical aesthetic. The inclusion of Virtual Families—a modern-day, The Sims-lite life simulation—as a “free bonus game” utterly shatters any pretense of thematic coherence, confirming that the pack was assembled from available inventory to maximize perceived value.

Technological and Market Constraints

The game was a DVD-ROM release for Windows, targeting the ubiquitous Windows XP and Vista systems of the time. The technological constraints were those of the casual game market circa 2009-2010: modest 2D graphics (often pre-rendered or simple vector-based), low system requirements to appeal to the “every-PC” audience, and installation sizes that fit comfortably on a single disc. Internet connectivity was not a assumed necessity for core gameplay, reflecting a market before the full dominance of digital distribution and always-online requirements. The PEGI 3 rating signals a deliberate design for absolute accessibility—no violence, minimal complexity, aimed at a broad family audience including children and older adults.

The Gaming Landscape of 2010

This compilation arrived at a pivotal moment. The “casual games” space, pioneered by PopCap and flourishing on platforms like Big Fish Games and Yahoo! Games, was mature and highly formulaic. Genres like mahjong solitaire, hidden object games (HOGs), and lightweight city-builders were reliable sellers. Simultaneously, the retail market for PC games was contracting, with brick-and-mortar space increasingly given to AAA titles or deep-discount compilations. The “Triple Pack” (or “Double Pack,” “Anthology”) was a staple of this discount bin, often bundling unrelated but similarly styled games from a single publisher’s catalog. Ancient Civilisations: Triple Pack is a quintessential example of this trend: low cost, low risk, high volume, capitalizing on a popular historical theme (Egyptology was experiencing a pop culture resurgence) to attract impulse buyers.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Study in Absent Genuine Narrative

A fundamental flaw in evaluating this compilation as a “game” is its utter lack of a unifying narrative or theme. The title promises a journey through ancient worlds, but the experience is four separate, mechanically-driven experiences with only superficial setting ties.

-

Empire Builder: Ancient Egypt presents the thinnest narrative veneer. The player is a “great architect” serving a series of unnamed “powerful pharaohs.” The goal is to “raise an ancient empire from the sands” along the Nile. This is not a story but a contextual mission brief for a city-builder. There are no characters, no dialogue trees, no plot twists—only a sequence of resource management and building placement challenges framed by Egyptian iconography (pyramids, sphinxes, obelisks). The “theme” is purely aesthetic, dressing a standard “build roads, gather resources, construct wonders” loop in sand and stone textures.

-

Liong: The Lost Amulets attempts a more explicit, albeit generic, narrative premise. The blurb describes a myth where “five magical amulets kept the natural elements in balance,” now lost, and the player must “restore harmony to nature.” This suggests a quest structure. However, based on genre conventions for such games (a mix of hidden-object scenes and tile-matching), this narrative would be delivered through brief, text-only interludes between levels, serving only to motivate the next puzzle. It is a MacGuffin-driven plot, existing to string together game mechanics, not to explore character or theme. The “natural elements” and “harmony” are abstract concepts with no deeper philosophical exploration.

-

Mahjongg Mysteries: Ancient Egypt offers a similar adventure-mode wrapper. The player is a “Mahjong adventurer” on a “search for the Lost Temple,” following “clues through the blistering sands… to the fertile banks of the Nile.” Again, this is a pure progression mechanic. The “mythical atmosphere” is conjured through background art and tile designs (ankhs, scarabs, hieroglyphs), not through narrative substance. The story is the path from Point A (desert) to Point B (pyramid) via mahjong boards.

-

Virtual Families is a complete outlier. Its narrative is emergent simulation: the player adopts a family of virtual people and guides their daily lives, careers, and homes. There is no ancient connection whatsoever. Its inclusion as a “bonus” highlights the compilation’s cynicism; it’s not part of the “Ancient Civilisations” brand but is thrown in to make the box feel more substantial.

Underlying Themes (or Lack Thereof)

The only unifying “theme” is cultural appropriation as aesthetic. All three themed games use the visual language of Egypt (and, by title extension, other ancient civs) without engaging with the actual history, mythology, or societal structures in any meaningful way. It is Egypt as a generic “ancient” setting—mysterious, monumental, and exoticized. The themes are therefore exploitation of historical mystique for commercial gamification. The deeper, complex themes of actual ancient civilizations—their religions, politics, social hierarchies, technological innovations—are entirely absent. The games reduce millennia of human history to a picturesque backdrop for puzzle-solving and resource gathering. This reflects a common, criticism-worthy trend in casual gaming: treating cultures as interchangeable, decorative skins for repetitive mechanics.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Four Genres in One Box

The compilation is a study in genre contrast, each title representing a distinct, established casual game subgenre with its own core loop.

-

Empire Builder: Ancient Egypt (City-Builder / Resource Management)

- Core Loop: Complete objectives for a Pharaoh by constructing specific buildings (houses, farms, quarries, workshops), managing a workforce, and maintaining resource flows (food, stone, gold). A typical mission might be “Build 3 pyramids and house 200 workers.”

- Systems: A simple economy where buildings cost resources and require workers. Players must balance food production with construction, often dealing with random disasters or enemy raids (lightly implemented). Progression is level-based, unlocking new buildings and challenges.

- Innovation/Flaws: As a late-2000s casual city-builder, it would be simpler and more guided than predecessors like Pharaoh or Caesar III. Innovation is minimal; it streamlines the genre to near-automation, with little strategic depth. A likely flaw is repetitive micromanagement with little lasting consequence, and a tutorial-heavy, hand-holding approach suitable for its PEGI 3 audience.

-

Liong: The Lost Amulets (Hidden Object / Tile-Matching Hybrid)

- Core Loop: A blend of two mechanics. Between hidden object scenes (find listed items in a cluttered static image), the player would engage in a tile-matching puzzle (like Mahjong or Bejeweled) to earn resources or progress.

- Systems: The hidden object scenes provide narrative advancement and currency. The tile-matching offers a skill-based diversion. Mini-games, as mentioned, would break up the flow.

- Innovation/Flaws: The hybrid model was common in casual games (e.g., Mystery Case Files series). Its flaw is often being neither good at hidden objects nor compelling at tile-matching, resulting in a diluted experience. The “100 levels of gameplay” suggests a long, grind-oriented progression with increasing object density or puzzle complexity.

-

Mahjongg Mysteries: Ancient Egypt (Mahjong Solitaire)

- Core Loop: The purest of the set. Clear a board of layered mahjong tiles by matching pairs of identical, unblocked tiles.

- Systems: Two primary modes: Adventure Mode (a linear path of boards tied to the “Lost Temple” story, with themed layouts) and Classic Mode (free-select from a library of 300+ boards, with 3 difficulty levels affecting tile layering and time limits).

- Innovation/Flaws: 300 levels was a major selling point for the genre. The “mysteries” and “Ancient Egypt” theme is purely visual on the tiles and backgrounds. The flaw is the inherent repetitiveness of mahjong solitaire; without compelling mechanical twists, enjoyment hinges entirely on the quality and variety of the board layouts.

-

Virtual Families (Life Simulation)

- Core Loop: Adopt a virtual person/family, assign them tasks (work, chores, skill training), manage their needs (hunger, hygiene, fun), and guide their life progression (career, relationships, children).

- Systems: A simplified, real-time simulation with a needs-based AI. The player issues commands (“Cook meal,” “Read book”) which the AI may or may not follow based on its mood and skill. The house is a customizable dollhouse-like environment.

- Innovation/Flaws: As a clear riff on The Sims, but far less complex. Its innovation was in its scale and simplicity for a casual audience. Major flaws include unpredictable AI leading to frustrating neglect of tasks, a lack of clear long-term goals, and a cosmetic focus over systemic depth.

User Interface (UI) and Installation Quirks

The source material provides a crucial piece of trivia: the user had installation problems with Liong: The Lost Amulets, resorting to manually copying files and finding that the installation process also included Liong: The Dragon Dance (presumably a different version or sequel). This reveals a key aspect of these budget compilations: shoddy, outsourced installation and patching. Each game installs to its own folder with no “install all” option, pointing to a lack of integration. The UI for each game would be its own native, period-appropriate interface, likely built in an older version of DirectX or a simple 2D engine, leading to inconsistent look, feel, and control schemes across the four titles. This fragmentation is a hallmark of the format—a value pack that offers no unified experience.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Atmospheric Window-Dressing

The artistic direction across the compilation is one of cost-effective theming.

- Visuals: Expect pre-rendered 2D backdrops and 2D sprite-based assets. For the Egypt-themed games, this means sandy color palettes (ochres, golds, blues), hieroglyphic patterns, and pixel-art or simple vector depictions of pyramids, palm trees, and pharaonic statues. The art is derivative, aiming for a “mystical ancient” vibe without historical accuracy. Virtual Families contrasts sharply with its bright, modern, cartoonish style. The overall quality is that of competent but unexceptional casual game art from the era—functional, clear, and themed, but not memorable or artistically ambitious.

- Sound Design: Sound effects would be standard library fare: clicks for tile selection, chimes for object finds, ambient loops (wind for Egypt, birds for Virtual Families). Music, if present, would be looping, royalty-free tracks in an “exotic” or “new age” style for the ancient games, and upbeat, simplistic tunes for the simulation. The goal is to create a low-stress, atmospheric backdrop, not an immersive soundscape.

- Atmosphere Contribution: The art and sound work to successfully create a genre-appropriate atmosphere. The Egypt-themed games feel vaguely “ancient” and “mysterious” at a surface level, which is all the narrative requires. They do not transport the player to a believable world; they provide a consistent, themed environment for puzzle-solving. Virtual Families creates a cozy, manageable domestic sphere. The atmosphere is one of casual comfort, not historical immersion or narrative tension.

Reception & Legacy: The Silence of the Budget Bin

Critical and Commercial Reception at Launch

Ancient Civilisations: Triple Pack exists in a historical void regarding critical reception. As confirmed by both MobyGames and Metacritic, there are no professional critic reviews recorded for this title. It was ignored by the games press, deemed unworthy of coverage beyond perhaps a listing in a “bargain bin” roundup. User reviews are similarly nonexistent on these platforms.

Its commercial life was almost exclusively through retail discount channels (Walmart, Target, PC budget software sections in the UK/Europe) and online marketplaces (as seen on eBay and Fruugo listings, often at low price points like £2.78 or $42.95 new). It was a shelf-filler, an impulse buy for a parent seeking a “safe” game for a child or an older adult looking for a simple puzzle. The PEGI 3 rating and clear genre labeling (Puzzle, as seen on eBay) were its primary marketing tools.

Evolving Reputation and Influence

The game’s reputation has not evolved; it has remained in a state of obscurity. It holds no cult following, speedrun community, or scholarly interest. Its legacy is purely as a data point in the history of game publishing.

1. The Decline of the Physical Compilation: The Triple Pack format, once common for PC games (see the “Related Games” list on MobyGames with entries from 1984 to 2015), was dying in 2010. Digital storefronts like Steam were solidifying their dominance, making physical multi-disc sets for casual games increasingly anachronistic. Ancient Civilisations: Triple Pack is one of the last gasps of this retail-focused model.

2. The Template of the “Theme Park” Compilation: It perfected a cynical but effective formula: find a timely, broad theme (Ancient Egypt, World War II, Mystery), bundle 3-4 otherwise unrelated butGenre-compatible games under it, add a “bonus” game to inflate value, and package for the lowest common denominator. This model is alive today in mobile game bundles and deep-discount Steam bundles, but the physical DVD version is a relic.

3. Archival Significance: Its primary value now is preservation. As hosted on the Internet Archive, it serves as a perfect specimen of early-2010s casual PC game compilation design—warts (installation quirks) and all. For researchers studying the casual game market, retail packaging, or low-budget game development, the ISO image is a primary source document.

Conclusion: A Verdict of Historical Record, Not Artistic Merit

Ancient Civilisations: Triple Pack is not a game to be judged by traditional standards of narrative, design innovation, or technical prowess. To do so would be to miss its point entirely. It is a commercial artifact, a product engineered for the bargain bin, not the critic’s desk.

Its individual components—Empire Builder, Liong, Mahjongg Mysteries—are competent, unremarkable representatives of their respective casual genres. They achieve their modest goals of providing low-stress, accessible puzzle or simulation gameplay wrapped in a familiar historic skin. Virtual Families is the oddest duck, a more ambitious (if flawed) life sim tacked on with no thematic justification, hinting at the compilation’s haphazard assembly.

The Triple Pack’s ultimate failure is its fundamental incoherence. The “ancient civilisations” theme is a marketing afterthought, exposed as hollow by the inclusion of Virtual Families. This lack of unity means the compilation has no greater whole to sum; it is merely the sum of its disconnected, disposable parts.

Final Verdict: As a gaming experience, Ancient Civilisations: Triple Pack is negligible—a forgettable collection of time-killers. As a historical document, it is immensely valuable. It crystalizes a specific moment in gaming: the last hurrah of the budget PC compilation, the formulaic peak of the casual puzzle genre, and the practice of theme-as-marketing-skin. It earns a place in history not for what it offers the player, but for what it reveals about the industry that produced and sold it. For archivists and historians of casual gaming, it is essential. For anyone seeking a meaningful game about ancient history, it offers nothing. Its score, therefore, is not a measure of quality but of historical specificity: it succeeds perfectly at being exactly what it was designed to be—a cheap, thematically vague, retail-oriented compilation—and in that, it is an unflinching success.