- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: PlayStation, Windows

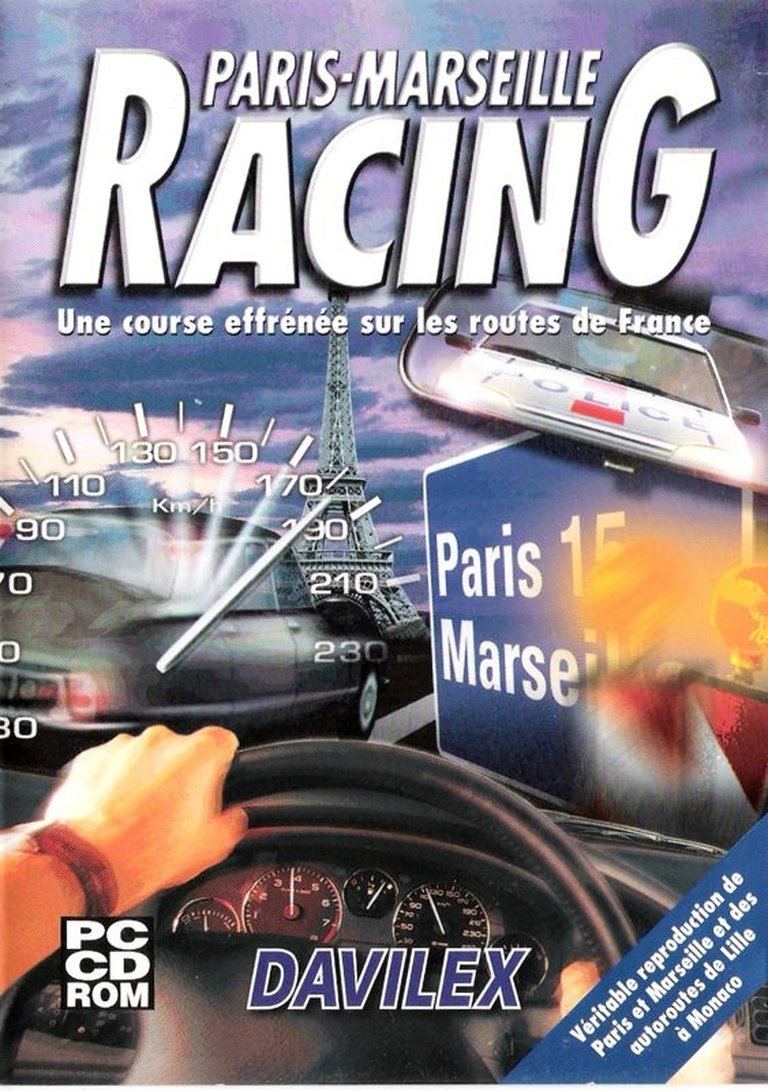

- Publisher: Davilex Games B.V.

- Developer: Davilex Games B.V.

- Genre: Driving, Racing

- Perspective: 1st-person, Behind view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Automobile, Street racing, Vehicle simulator

- Setting: France, Paris

Description

Paris-Marseille Racing is an arcade-style street racing game set in France, where players compete in tournament, time attack, and single race modes by driving vehicles like the DeLorian, police car, Mini, or Beetle along famous roads from Paris to Marseille. Racers must secure first-place finishes across three classes to earn cash for upgrading cars with enhanced engines, tires, and nitro boosts, reflecting the fast-paced, vehicular action of Davilex Games’ regional Racer series.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Paris-Marseille Racing

PC

Paris-Marseille Racing Cracks & Fixes

Paris-Marseille Racing Cheats & Codes

PlayStation (PAL)

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| 800D5C20 869F | Have 99999 money |

| 800D5C22 0001 | Have 99999 money |

Paris-Marseille Racing: A Study in Budget Gaming’s Lowest Common Denominator

Introduction: The Asphalt Low-Water Mark

To understand Paris-Marseille Racing is to understand the seedy underbelly of the turn-of-the-millennium European budget software market. Released in October 2000 by the Dutch studio Davilex Games, this title is not merely a bad racing game; it is a meticulously constructed artifact of cynical commercial expediency. It represents the nadir of the “localized reskin” strategy, where a single, mediocre game engine is repackaged with new menus, minimal cosmetic changes, and region-specific branding to be sold across multiple European markets at a cut-rate price. Its legacy is not one of innovation or fond memory, but of a stark cautionary tale about how not to design, market, or support a video game. This review will dissect Paris-Marseille Racing not as a game to be played, but as a historical document—a case study in stripped-down development, cultural superficiality, and the absolute collapse of quality control.

Development History & Context: The Davilex Assembly Line

The Studio and Its Model: Davilex Games B.V. operated on a unique, assembly-line philosophy. The source material reveals a core team of approximately 36 developers credited on the Windows version, with many names (Jelle van der Beek, Jeroen Krebbers, Kent Kuné) appearing repeatedly across the “Davilex Racer series” entries listed on MobyGames and Wikipedia. This suggests a small, core technical and artistic team that was constantly recycling assets, code, and design across multiple projects. The series timeline is illuminating: it began with A2 Racer (Netherlands, 1997) and rapidly expanded to Autobahn Raser (Germany, 1998), London Racer (UK, 1999), and finally Paris-Marseille Racing (France, 2000). Each was ostensibly a unique title set on a famous national roadway—the A2, the Autobahn, the M25, the route nationale 7—but PCGamingWiki delivers the crucial bombshell: Paris-Marseille Racing is, in fact, a French-localized version of the Dutch game A2 Racer III: Europa Tour. It uses the tracks and sound effects from another title, Holiday Racer, combined with the cars, menus, and soundtrack from A2 Racer III. This is not a sequel or a cousin; it is a direct reskin.

Technological Constraints and Ambitions: The game’s specs (a Pentium 166 MHz CPU, 16 MB RAM, 50 MB install) place it firmly in the era of late-90s/early-2000s budget PC gaming. It targets Direct3D 5, with a software rendering fallback, indicative of a project built on an aging or severely limited in-house engine. The existence of a PlayStation port (SLES-03108) points to a low-cost conversion, likely handled by external teams like Spesoft/Headsoft (as seen on GamesDatabase.org), utilizing the PS1’s basic 3D capabilities. The development vision, as outlined in the basic description, was absurdly simple: “Take control of your DeLorian, police car, Mini or Beetle and race through some of France’s most famous (and busiest) roads and cities.” This was not a creative vision but a checklist of marketable European icons (DeLorean, Eiffel Tower implied) and a core gameplay loop (race, earn cash, upgrade) copied from more successful arcade racers like Need for Speed.

The Gaming Landscape: 2000 was the golden age of the PlayStation and the rise of the PC as a gaming platform. However, the budget segment was flooded with titles like Davilex’s, which competed on price and recognizable locales rather than quality. They stood in stark contrast to the critically acclaimed sims (Gran Turismo 2, Need for Speed: Porsche Unleashed) and innovative arcade racers (Rollcage, Re-Volt). Davilex occupied a uniquely disreputable niche, with Wikipedia noting that “la série a toujours très majoritairement reçu des critiques médiocres comme la plupart des jeux à petits budget produits par Davilex.”

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Void

Here lies the game’s most profound and telling failure: there is no narrative, no thematic depth, and no meaningful characters. The Wikipedia entry and all official descriptions treat the “plot” as a throwaway line: police will chase you. This is not a story-driven game; it is a pure mechanics-driven exercise. The only “theme” is the hollow concept of “driving really fast past famous French monuments.” The lack of any narrative framework is not an oversight but a design philosophy. Davilex aimed for the lowest possible creative common denominator, assuming the player’s interest would be sparked solely by the setting (Paris, Marseille) and the vehicles (a DeLorean, a police car). This approach strips the racing genre of any context—no underground scene, no career progression with rivalries, no reason to care about the races beyond the immediate cash reward. The game is a thematic vacuum, which makes its critical drubbing for lacking “un sentiment de liberté de circuler ou un environnement crédible” (Gamekult) particularly ironic. It offers neither freedom nor credibility because it was never designed to; it was designed to be a cheap, disposable product.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Jank in Motion

Core Loop and Structure: The game offers three modes: Tournament, Time Attack, and Single Race. The stated goal is to “place first” in one of three car classes to earn cash for upgrades (engines, tires, nitro). This is a standard arcade racer progression skeleton. However, the execution is where the game collapses. The source material is silent on precise handling physics, but the universal critical condemnation points to a core experience that is “maladroite” (clumsy) and “burlesque” (ridiculous). Cars likely have unresponsive steering, weightless feel, and a complete disconnection from the road surface.

The “Police Madness” Variant: The PlayStation cover text (PSXDataCenter) explicitly warns: “Mais attention : la police n’hésitera pas à vous prendre en chasse !” (But watch out: the police won’t hesitate to chase you!). This suggests a spin-off or variant mechanic, perhaps in a later release like Paris-Marseille Racing: Police Madness (2005, per Wikipedia). However, the base 2000 game’s description does not emphasize this. If present, it would be a rudimentary “wanted level” system, likely implemented with the same janky AI that critic reviews would deride as “injouable” (unplayable).

UI and Systems: With a development team of 36, the UI was certainly a minimal, functional afterthought. There is no indication of a robust garage, nuanced tuning, or a dynamic map. The upgrade system (“enhanced engines, tires and even a nitro boost”) is almost certainly a simple, linear cash-for-stats transaction with no meaningful impact on car handling characteristics—just numerical increases in a top speed or acceleration stat that may be imperceptible in-game.

Innovation? There is none. Paris-Marseille Racing exists in a state of pure derivative inertia. It takes the basic shell of a mid-90s arcade racer, places it on tracks that are presumably poorly modeled versions of French roads, and calls it a day. Its only “innovation” is the business model of rapid, low-cost regional localization.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Postcards from a Broken Render

Visuals and Setting: The game’s world is its primary (and failed) selling point. The back cover boasts of driving “des ruelles de Marseille aux grandes artères parisiennes” (from the alleys of Marseille to the grand boulevards of Paris). Gamekult’s review savages this premise: the realism is a façade built on “des monuments mal texturés en 3D” (poorly textured 3D monuments). This paints a picture of low-poly models with blurry, stretched textures—a “postcard” aesthetic that collapses under scrutiny. The tracks are likely straight-line interpretations of famous roads with no traffic density, pedestrian life, or architectural authenticity. The “busiest roads” promise is almost certainly a lie, replaced by empty asphalt. The art style, per PCGamingWiki, is listed as “Realistic,” but this is a technical descriptor, not an artistic achievement. It is the realism of a dot-matrix printer versus a photograph.

Sound Design and Localization: This is where the game achieves a perverse kind of infamy. As noted by a user on MyAbandonware in 2024: “the best part was the radio chatter in broken French.” This anecdote is priceless. It suggests the audio implementation was not merely bad but charmingly, hilariously inept. The “broken French” implies either a machine translation read by a non-native speaker or a pitch-shifted asset from the original Dutch version. This audio glitch becomes the game’s most memorable feature—a serotonin-free version of the “so bad it’s good” phenomenon. The soundtrack is presumably a collection of generic, low-bitrate techno or pop loops, utterly forgettable.

Atmosphere: The combined effect is one of profound loneliness and falseness. You are alone on a Sunday-morning-empty Champs-Élysées, pastel-colored buildings flickering in the distance, while a tinny, distorted voice on the radio mangles the French language. It is the aesthetic of a forgotten demo disc, not a world to inhabit.

Reception & Legacy: A Parade of One-Star Reviews

Critical Reception at Launch: The numbers are brutal and unequivocal. MobyGames aggregates a 18% average critic score based on two contemporary reviews.

* Gamekult (France): 20% – Calls it a “pseudo-course automobile” (pseudo-racing game) where the realism claim is based only on poorly textured 3D monuments. It finds the execution “maladroite” at best, “burlesque” at worst, and concludes it is a “pseudo-jeu ne méritant pas le détour” (pseudo-game not worth the detour).

* Jeuxvideo.com (France): 15% – Dubs it “Paris-Marseille Racing Police Madness” in its headline, summarizing it as “injouable, mal pensé, répétitif et lassant” (unplayable, poorly conceived, repetitive, and boring). It declares it “l’un des plus mauvais jeux de courses de ces derniers mois” (one of the worst racing games in recent months) and典型 “du grand Davilex” (typical great Davilex—heavy sarcasm).

Player Reception: The two user ratings on MobyGames average a miserable 0.8/5. The game is, for all intents and purposes, abandoned by its audience.

Long-Term Legacy and Influence: The Wikipedia entry for the series is a litany of similar failures. Every entry listed—from A2 Racer (1997) to Paris-Marseille Racing: Destruction Madness (2005)—is noted for receiving “des critiques médiocres.” The series peaked, if one can call it that, with London Racer (1999) getting an 8/10 from GameSpot UK, an outlier that remains unexplained. Most sequels fared worse: Europe Racing (2001) got 3/10, Paris-Marseille Racing II (2002) got 2/10 and 1/20, and later titles scraped by with slightly higher but still abysmal scores (6/20, 7/20). The only tangible cultural spillover was the 2004 German film Autobahn Raser, a film adaptation of the German version of the game—a testament to the series’ niche notoriety, but not a mark of quality.

Its influence is negative and cautionary. Paris-Marseille Racing exemplifies the “asset flip” and regional reskin long before those terms were common. It demonstrates a complete disregard for player experience, focusing solely on the cheapest possible path to a shelf-ready product. It lives on only in the form of abandonware downloads (MyAbandonware) and as a trivia question for speedrunners and historians. Its legacy is a warning label: “Here lies the cost of cutting every corner.”

Conclusion: The Unflattering Truth

Verdict: Paris-Marseille Racing is a historical footnote, not a playable game. It is a 0/10 experience by any meaningful metric of game design: mechanically broken thematically hollow, artistically bankrupt, and aurally grating. Its sole historical value is as a pristine example of the low-budget, region-locked software dump that cluttered European retail shelves in the early 2000s. It proves that a recognizable city name and a list of famous cars are insufficient substitutes for competent programming, thoughtful design, or artistic vision. The game is not “so bad it’s good”; it is so cynically, transparently bad that it inspires only pity and scholarly disdain. Its place in video game history is as a cautionary benchmark—the absolute floor against which the quality of other titles can be measured. It is the gaming equivalent of a plastic Eiffel Tower keychain: instantly recognizable, utterly worthless, and destined for the bargain bin and the archives of the curious.

Final Score: Not Applicable. This game cannot be scored on a scale of quality. It exists on a separate axis of commercial and creative failure.