- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Freeverse, Inc.

- Developer: Freeverse, Inc.

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Cards, Tiles

Description

3D Spades Deluxe is a digital adaptation of the classic Spades card game, set in an immersive 3D first-person environment that distinguishes it from traditional top-down 2D card games. Players can enjoy single-player matches against AI opponents or engage in online multiplayer for up to four participants via the GameSmith service, with features like interchangeable characters, customizable rules and difficulty levels, varied backgrounds, and a tutorial to assist new players.

3D Spades Deluxe Free Download

3D Spades Deluxe: A Pioneering Yet Forgotten Artifact of Digital Card Gaming

Introduction: The Spades Gamer’s Immersive Dream, Realized?

In the vast and varied history of video games, certain niches remain underexplored by historians: the humble computerized card game. For decades, digital adaptations of classics like Solitaire, Bridge, and Spades existed in a state of functional, often abstract, minimalism—a clean table, flat cards, and stat-driven opponents. Against this backdrop of 2D tabletop simulations, 3D Spades Deluxe emerged not as a revolutionary narrative epic, but as a quiet, technically audacious reinvention of a social pastime. Released by Freeverse, Inc. in 2000 for Macintosh (with a Windows port following in 2002), it dared to ask: what if playing a hand of Spades felt like you were there? This review posits that while 3D Spades Deluxe may be a footnote in gaming history, its core innovation—a first-person, 3D-rendered environment for a trick-taking card game—represents a fascinating, if ultimately niche, experiment in virtual presence and social avatars. Its legacy is not one of critical acclaim or commercial blockbuster status, but of a specific, ambitious design philosophy that would later permeate the broader industry, even if this particular title did not survive to see its ideas become mainstream.

Development History & Context: Freeverse’s Niche and the Dawn of “3D Deluxe”

The Studio and Its Vision:

Freeverse, Inc. was a quintessential player in the Macintosh shareware and independent software scene of the 1990s and early 2000s. Unlike studios chasing AAA console markets, Freeverse carved out a profitable and beloved niche with accessible, often whimsical utilities, and a series of “3D Deluxe” card games (including 3D Bridge Deluxe, 3D Hearts Deluxe, 3D Pitch Deluxe, and 3D Euchre Deluxe). Their expertise lay in taking familiar, rules-heavy card games and wrapping them in colorful, character-driven, 3D interfaces that felt more like interactive toys than dry simulations. 3D Spades Deluxe was a flagship product in this line, representing the culmination of their template applied to one of partnership trick-taking’s most popular variants.

Technological Constraints and Ambitions:

The game’s development straddled a pivotal period. For Mac OS 8/9 and early Windows 95/98/XP systems, 3D acceleration was becoming standard but not yet ubiquitous. The requirement for “16 MB VRAM minimum” (as noted in the GameSpy specs) was a genuine threshold for smooth performance. Freeverse’s engine, shared across the “3D Deluxe” series, was a custom-built solution focused on real-time, low-polygon character models (“puppets”) and static but artistically rendered environments. The ambition was to create a sense of place—a “magical garden or a scary haunted house”—with limited resources. This necessitated clever use of pre-rendered backdrops with animated foreground elements and simple, textured 3D character models that could “talk” via basic animations. The shift from a top-down 2D table to a first-person perspective was not merely a graphical toggle; it required a complete rethinking of user interface, spatial cues for card play, and the very psychology of “opponent” presence.

The Gaming Landscape:

In 2000, the online gaming landscape was dominated by dedicated FPS, RTS, and MUD/MO clients. For casual and card gamers, options were fragmented: AOL’s lightweight card rooms, Yahoo! Games’ Java-based tables, or standalone applications like Microsoft’s Gaming Zone clients. The concept of a dedicated, graphical client for a single card game with its own online service (GameSmith) was specialized but not unprecedented. Freeverse’s target audience was the Mac-centric home user and the enthusiast of classic card games who wanted more personality than Microsoft’s Solitaire Collection could offer. The release timing also coincided with the growing mainstream acceptance of broadband, making persistent online play more viable, though still a premium feature.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Story of the Table

It is a crucial and honest point of analysis: 3D Spades Deluxe has no traditional narrative, no plot, no characters with arcs, and no dialogue with literary merit. As a card game simulation, its “story” is purely emergent and player-driven: the story of a particular hand, a comeback bid, a successful nil, or a crushed partnership. However, to dismiss this as a lack would be to miss the game’s subtle thematic and narrative-adjacent design.

The Thematic Construct of “Persona”:

The game’s most significant narrative-adjacent feature is its system of interchangeable, talking opponents. The source material lists examples: “a monkey? An alien? Sue, the archaeologist or even the Mini-Queen herself.” These are not merely cosmetic skins; they are “personas” with implied identities and behaviors. The archaeologist “Sue” suggests a backstory; the “Mini-Queen” implies a regal, perhaps imperious, personality. The fact that they “talk”—likely via sampled voice lines or text-based banter—creates a fictional layer. Each hand becomes a social interaction with a cast of characters, however superficial. The player is not just playing against an AI algorithm labeled “Advanced”; they are playing against “Gronk the Alien” or “Maggie the Garden Gnome.” This injects a dose of playful fiction into every round, transforming abstract probability into a social skirmish with distinct personalities.

World-Building as Environmental Storytelling:

The choice of backgrounds—”a magical garden or a scary haunted house”—functions as pure environmental storytelling. The setting is not a neutral void; it is a stage that influences mood. A haunted house background with spooky music and creaking floorboards (as implied) frames the game as a high-stakes, eerie contest. A magical garden, with fairies and soft light, frames it as a lighthearted, whimsical duel. The game world is the card table itself, and its decoration directly informs the player’s emotional engagement with the same set of rules. The narrative is the progression from one themed environment to another, a curated tour of atmospheres for the same core activity.

The Player as Protagonist:

Ultimately, the player is the sole protagonist. The game’s “drag & drop” feature to “put your own face in the game” is the ultimate narrative device. It collapses the distance between player and avatar, making the first-person view truly personal. The story becomes: “I, in my haunted study, partnered with a wise-cracking monkey, against the scheming archaeologist and her silent alien henchman, bid a daring nil and pulled it off.” The narrative emerges from the collision of the player’s self-insertion, the chosen AI personas, and the selected atmospheric setting. It is a lightweight, procedural storytelling system, brilliant in its simplicity for a card game.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Study in Accessible Depth

Core Loop and Innovation:

The fundamental loop of Spades—bid, play tricks, score—is rendered with remarkable fidelity. The innovation lies entirely in presentation and interaction. Bidding and card selection occur by clicking on 3D models of cards that fan out in front of the player in a first-person view. The “felt” of the table is replaced by a textured 3D surface. Playing a card involves clicking on your card in hand, which then animates forward to the “center” of the virtual table. Opponents’ cards animate into play from their respective avatar positions. This creates a powerful sense of spatial continuity absent in top-down designs. You see the card leave your hand, travel through the air, and land on the table, with your partners’ and opponents’ avatars visually reacting (nodding, shaking heads, smiling).

AI and Difficulty:

The system offers “novice and advanced skill settings” and “difficulty levels ranging from easy to cutthroat.” While the source material provides no algorithmic details, the range suggests a sophisticated AI for the genre. It must not only play legal cards but also engage in partnership signaling (a critical advanced Spades tactic), manage risk based on bids, and potentially adapt to player patterns. The mention of “cutthroat” implies an AI that does not forgive mistakes, making it a credible training tool. The presence of a “full tutorial” is essential, as the 3D perspective could initially confuse players accustomed to a clear, top-down overview of all hands.

Customization as a Game System:

The most profound mechanical depth comes from the customization suite:

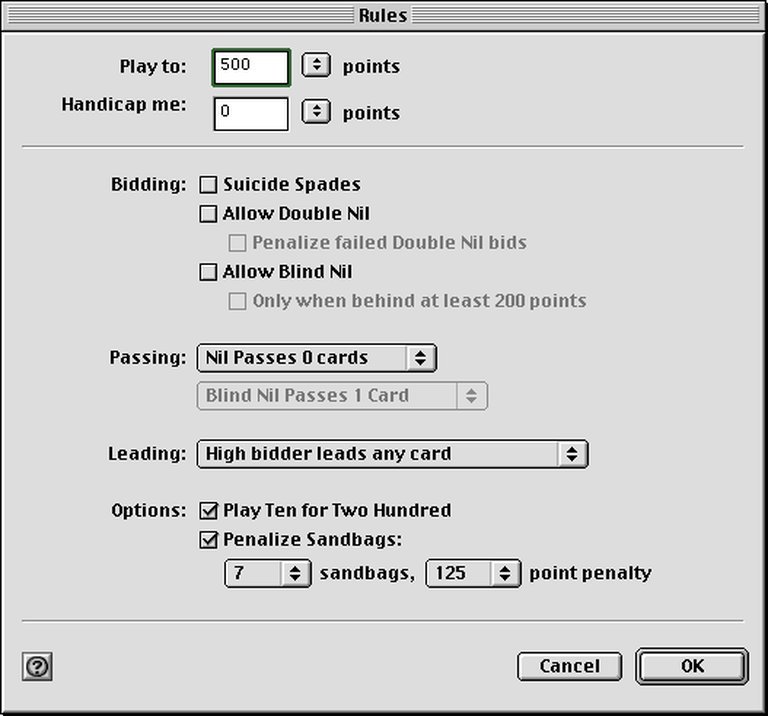

* Rule Variations: “Support for the most popular rule variations” (e.g., setting bags, nil bonuses, passing cards between partners) allows players to tailor the game’s scoring and strategy to their house rules. This transforms the game from a fixed system into a flexible framework.

* Character & Background Selection: Choosing opponents and the table’s environment is not merely aesthetic; it’s a system for altering the game’s psychological feel and perceived challenge (is the “scary haunted house” AI more aggressive?).

* Personal Avatar: The “drag & drop” face insertion is a groundbreaking feature for its time in a card game, merging the player’s real identity with their virtual persona at the table.

UI and Interaction:

The “Point and select” interface is deceptively simple. The challenge was translating the clear, information-dense layout of a physical card table into a 3D space without cluttering the view. The UI likely utilizes a clean, overlay-based system for bids, scores, and trick history that appears contextually, preserving the immersive 3D view while providing necessary data. The success of this system is key to the game’s playability. A poorly implemented 3D view could obscure crucial information, but the game’s apparent longevity and positive word-of-mouth (implied by the single 5.0 rating on MobyGames) suggest Freeverse succeeded in balancing immersion with utility.

Flaws and Limitations:

Based on the preservation community notes (Macintosh Garden), the game’s technical implementation had fragility. The discussion of missing “plugins” folders and broken “symbolic links” for different OS versions indicates a complex, perhaps over-engineered, packaging system for the era. This suggests a potential downside: the ambitious 3D engine may have introduced installation and compatibility hurdles that simpler 2D games avoided. Furthermore, the first-person perspective inherently limits the player’s simultaneous view of all four hands (a natural advantage in a top-down view), which could be a deliberate design choice to increase difficulty or a genuine limitation for tracking card distribution.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Atmosphere of a Hand

Visual Direction:

The art style is low-polygon, stylized, and character-focused. The priority is on expressive, talking avatars (“3D animated, interchangeable, talking opponents”) rather than photorealism. The environments—a “magical garden” or “haunted house”—are likely static, painted backdrops with looping particle effects (fireflies, fog) and animated foreground objects to create depth. This was a smart artistic compromise: it allowed for distinct, memorable visual themes without demanding high-end hardware. The characters, as “puppets,” have a charming, toy-like quality consistent with Freeverse’s broader design language (evident in their other “3D Deluxe” titles and the related “Colin’s Classic Cards” assets).

Sound Design:

The soundscape is composed of three layers:

1. Ambient Tracks: Different musical themes for each background location (soothing melodies for the garden, ominous tones for the haunted house) that set the emotional tone.

2. Interactive SFX: The clink or slide of cards being played, the shuffle of the deck, the dealing animation sounds. These provide crucial audio feedback for actions in the 3D space.

3. Character Vocalizations: The “talking” opponents. The source doesn’t specify if these are full voice-overs or simple exclamations (“Oh, well played!”, “A bogey!”). Even limited barks would significantly enhance the feeling of playing against living personalities rather than silent bots.

Contribution to Experience:

These elements synthesize to create what we might call “social ludic immersion.” The goal is not to simulate a realistic casino or a gritty war room, but a friendly, personality-rich game room. The art and sound design work to make the computer opponents feel like friends (或 rivals) you’ve invited over for a game. The environments are not players; they are the venue. This is a deliberate departure from the abstract, universal table of most card sims. It says: “Spades can be played in a garden, a dungeon, or a spaceship; let’s make that part of the fun.” The experience is thus heavily flavored by the player’s aesthetic choices, making each session qualitatively different based on the chosen “skin” for the game itself.

Reception & Legacy: A Quiet Cult Classic

Contemporary Reception:

Documented critical reception is virtually non-existent. Metacritic lists “critic reviews are not available,” and MobyGames shows a single 5.0 user rating with zero written reviews. This silence is itself data. The game existed in a pre-YouTube, pre-widespread game-blogging era for a niche audience. Its marketing was likely through shareware listings ( Tucows rating: 5), Mac-specific magazines, and word-of-mouth among card game enthusiasts. The fact that it was preserved and is still discussed in retro Mac communities (Macintosh Garden) indicates it found a dedicated, if small, user base. The GameSpy and IGN listings, with their boilerplate descriptions, suggest it was cataloged but not critically engaged with by mainstream outlets of the time.

Evolution of Reputation:

Its reputation has evolved from a forgotten shareware title to a curated artifact of preservationist interest. Within the community dedicated to saving classic Mac software, 3D Spades Deluxe is valued for:

1. Its representation of Freeverse’s “3D Deluxe” series style.

2. Its functionality as a still-playable, networked card game on vintage systems.

3. Its role in the ecosystem of “puppet” assets shared between it, Colin’s Classic Cards, and other Freeverse titles.

It is no longer judged as a mainstream game but as a historically significant piece of niche software that exemplified a certain Mac gaming aesthetic—playful, accessible, and technically competent within constraints.

Influence and Industry Place:

The game’s direct influence on the broader industry is difficult to trace. It did not invent the 3D card game (earlier attempts existed) nor did it popularize the concept. However, its core idea—using a first-person perspective and personalized avatars to enhance social presence in a digital tabletop game—is a clear conceptual ancestor to modern phenomena:

* VR Tabletop Simulators: Games like Tabletop Simulator and dedicated VR poker/social games prioritize user presence and table customization, directly extending the goal of “feeling there” that 3D Spades Deluxe pursued with far simpler tech.

* Social Casinos and Digital Board Games: Modern digital adaptations of board games and casino games often feature elaborate 3D tables, animated player pieces (avatars), and themed environments. The philosophy of dressing up the rules in a world is now standard, and 3D Spades Deluxe was an early, pure execution of this for a card game.

* The “Avatar” as a Player Proxy: The drag-and-drop face feature is a primitive but direct lineage to today’s ubiquitous profile pictures and custom avatars in every online multiplayer experience. It treated the player’s identity as a core game component.

Its place in history is therefore as an influential prototype. It proved that even for a rules-heavy, non-action game, a sense of place and personalization could be a primary selling point. It demonstrated that “immersion” did not require a first-person shooter; it could be achieved at a card table with the right combination of perspective, sound, and avatar.

Conclusion: A Defining Curio of a Bygone Design Ethos

3D Spades Deluxe is not a “great” game by conventional metrics. It lacks a story, it did not redefine its genre for the masses, and it faded into near-total obscurity. Yet, to judge it solely on those terms is to miss its quiet brilliance. It is a masterclass in design focus and thematic consistency. Every system—from the first-person view and talking puppets to the themed backgrounds and personal avatar upload—served a single, coherent vision: to make the digital act of playing Spades feel more like a social event in a specific, playful locale.

Developed within the constraints of late-90s shareware, it achieved a technical and aesthetic charm that still resonates in preservation circles. Its legacy is a whisper in the code of modern social gaming: the idea that the space you play in and the face you present are as important as the rules themselves. For historians, 3D Spades Deluxe is an essential study in how independent studios used the tools of their time to solve the timeless problem of digital social presence. It is a game not about saving the world or telling a story, but about holding a hand of cards across a virtual table and believing, for a moment, that your opponent the monkey is really judging your bid. In that specific, modest goal, it was a resounding success.