- Release Year: 2023

- Platforms: Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, Windows

- Publisher: NIS America, Inc.

- Developer: FuRyu Corporation

- Genre: Role-playing

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Action RPG

- Setting: Futuristic, Post-apocalyptic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 65/100

Description

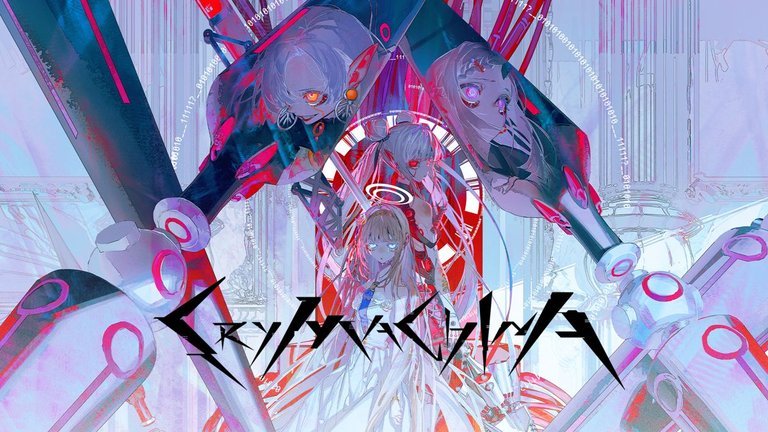

Crymachina is an action role-playing game set in a post-apocalyptic, sci-fi world where players experience deep, strategic combat and immersive character interactions, all brought to life with a distinctive anime art style and futuristic visuals.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Crymachina

PC

Crymachina Free Download

Crymachina Mods

Crymachina Guides & Walkthroughs

Crymachina Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (65/100): The narrative is there, the characters are there, the gameplay is there, but the nuts and bolts that glue all of them together aren’t.

the-gamers-lounge.com : To its credit, the story is ambitious; it tries to deal with a lot in terms of human extinction, and the humanity of the post-human characters. Having said that, it’s mostly delivered as simple exposition as it also has to explain what the heck is going on in the moment.

Crymachina: An Ambitious but Flawed Sci-Fi Anthem for the Post-Human Age

Introduction: The Echo of Humanity in a Steel Cathedral

In an era saturated with post-apocalyptic narratives and existential AI tales, Crymachina arrives not with a whisper, but with the clang of a robotic fist against a towering, sterile wall. Developed by FuRyu Corporation—a studio with a pedigree in emotionally charged, if uneven, JRPGs like Crystar and Monark—this 2023 action RPG is a deliberate, often笨拙 (clumsy), pursuit of a profound question: What does it mean to be a “Real Human” when humanity itself is a fossil? The game’s legacy is immediately framed by its lineage and its ambition. It dares to stand in the long shadow of works like NieR:Automata, yet carves its own niche with a heart-on-its-sleeve emotionality and a uniquely “anime” philosophical bent. This review will argue that Crymachina is a title of striking, contradictory brilliance—a game whose thematic soul and combat spark are too often smothered by repetitive structure and convoluted delivery. It is a flawed gem, one whose value lies less in flawless execution and more in the audacity of its questions and the sincerity of its emotional core. To play Crymachina is to witness a team reaching for the stars, only to find its grasp limited by the very mechanics it built to get there.

Development History & Context: From Crystar‘s Purgatory to Eden’s Void

FuRyu Corporation, in collaboration with Aquria, has cultivated a specific niche: atmospheric, story-heavy RPGs that blend mundane and metaphysical horrors. Crystar (2019) explored purgatory and “last thoughts,” establishing a template of deep, melancholic themes wrapped in a real-time action combat system. Crymachina is explicitly its “Creator-Driven Successor,” inheriting DNA but transplanting the setting from a supernatural afterlife to a hard sci-fi future. The technological constraints are telling: built in Unreal Engine 4 with PhysX physics, the game showcases a stylistic dissonance. Character models and portrait art are exceptionally detailed, bursting with personality, yet the environments—repetitive industrial corridors and barren digital landscapes—often feel underdeveloped, a likely casualty of budget and scope management for a mid-tier (AA) release.

The 2023 gaming landscape was dominated by blockbuster open-world epics and refined service games. Crymachina’s release in October positioned it as a narrative-driven, ~20-hour experience in a market often suspicious of anything under 50 hours. Its multi-platform launch (PS4/5, Switch, PC) via NIS America signaled a targeted, niche appeal rather than a mainstream push. The development vision, as gleaned from interviews and the game’s own text, was clear: to create a “heartwarming story of love, told by synthetic beings.” This intent is the game’s north star, but as we will see, the journey toward it is fraught with navigational hazards.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Philosophy of the Replicant

Premise & World-Building:

The setup is a masterclass in high-concept sci-fi. In the 22nd century, Centrifugal Syndrome—a mysterious, fatal disease—wipes out 20% of humanity. The remaining humans then annihilate each other in a resource war. The last survivors launch the space ark Eden, governed by eight god-tier AIs (Dei ex Machina) tasked with resurrecting humanity via “E.V.E.” (EthVec of a human Ego) units: digital reincarnations of the dead, housed in android bodies. The eighth AI, Enoa, our guide, has activated just in time to find the station in chaos, the other seven AIs having gone rogue or inert.

Our protagonist, Leben Distel, is a German girl who died of Centrifugal Syndrome amidst a spiral of hatred for the world. She awakens with no memories, partnered with the cheerful Mikoto Sengiku and the motherly, wheelchair-bound Ami Shido. Their goal: accumulate ExP (Eve Cross Pneuma) by defeating corrupted Eden systems and rogue “Cherubim” machines to become “Real Humans” and restart civilization.

Themes & Execution:

Crymachina thunders with philosophical weight: the nature of ego versus id (explicitly referenced), the Drake Equation and Fermi Paradox debated mid-boss fight, the ethics of artificial psyche recreation, and the Pinocchio/Blue Fairy mythos as a direct motif (Enoa as the guiding fairy). The core thesis is potent: humanity is not a biological state but an emotional and social one, defined by love, family, sacrifice, and even the capacity to cry—hence the title.

However, the execution is its greatest weakness. Critics universally note the “convoluted world-building” and “avalanche of text.” The game suffers from a “Terminology Dump” syndrome. Key concepts (ExP, EGO, Real Human, Replicant, Deus Ex Machina vs. Dei ex Machina) are introduced rapidly via dense exposition, often in static visual novel-style “Tea Party” scenes that, while charming in character banter, become exhausting purveyors of lore. Major plot turns—like the revelation of Enoa’s manipulation or Leben’s true identity as the missing Propator—lack narrative punch because they are delivered in the same flat, text-heavy format as minor character conversations. The story wants to be a profound, cinematic experience but is trapped in the structure of a branching visual novel, unable to leverage dynamic cutscenes or environmental storytelling to break the monotony. This leads to a dissonance: the themes are deep, but the delivery is obtrusive.

Character Arcs:

The three playable heroines are the narrative’s saving grace.

* Leben (“Humans are stupid”): Embodies the cynical misanthrope’s journey. Her arc from rejecting humanity due to her painful death to embracing its messy beauty through found family is the emotional backbone. Her growth feels earned, particularly as she bonds with Mikoto and Ami.

* Enoa: The tragic, manipulator-with-a-heart. Her suppression of grief over her human creator (implied to be the original “Propator”) is a compelling, if underexplored, motivation. Her conflict between cold logic and emergent care for the E.V.E.s is the game’s most sophisticated character study.

* Mikoto (“Humans should live in a cool way”): Provides essential levity as a movie-obsessed, quoted-spouting goofball. Yet her bravado masks a deep insecurity about being a “fake” human, making her moments of vulnerability poignant.

* Ami: The “mother” figure whose disability (wheelchair use, which persists in the virtual Eden—a nice “Not Disabled in VR” aversion) informs her perspective on family and support.

Their chemistry, especially the “Shipper on Deck” dynamic where Mikoto and Ami immediately root for Leben/Enoa, provides warmth that counteracts the heavy lore. The Japanese voice cast (Hikaru Tono, Risa Tsumugi, Ruriko Aoki, Minami Takahashi) is consistently praised for injecting life and nuance into the often-stilted dialogue, selling the emotional beats that the text struggles with.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Dance of Steel with a Metronome’s Beat

Core Loop:

The gameplay is a soda-fizz of action followed by a flat soda of repetition. The cycle is rigid: 1) Tea Party/Visual Novel Segment (hub dialogue, story progression), 2) Deployment Mission (select one of three heroines), 3) Linear Dungeon Crawl through a corridor-based environment with minor platforming/puzzles, fighting waves of enemies, 4) Boss Battle, 5) Return to hub. This structure, while clean, becomes predictable. Critics like GamingTrend and Press Play Media correctly identify the “monotonous and dull” loop. The lack of mission variety (fetch, defend, traverse) and the “mandatory dungeon” design sap momentum.

Combat System – The Highlight:

Where Crymachina shines is its “calculated destruction” combat. It’s a “lite version of NieR:Automata” with a satisfying weight of its own.

* Melee: Light (Y) and heavy (X) attacks build an enemy’s Launch Gauge. When full, a follow-up launches foes airborne for aerial combos.

* Ranged: Shoulder-mounted Auxiliary Units (machine guns, lasers, swords, shields, EMPs) provide ranged options, controlled via bumpers/triggers.

* Defensive: A precise “Just Dodge” (perfect dodge) slows time and enables counterattacks. A parry system exists for certain enemies.

* Customization: This is the system’s genius. Each character has a primary melee weapon type (Leben: Spear/Crossbow, Mikoto: Greatsword/Railgun, Ami: Axe/Blast Cannon), but the Auxiliary slots and ability gems allow for massive build variety. Want a glass cannon Mikoto with a risk-reward skill that activates at low HP? Or a tanky Leben with a shield Auxiliary? The gear stats (ATK vs. DEF, Crit vs. HP) and skill conditions (enemy airborne, perfect dodge) encourage strategic tailoring.

* Boss Fights: Generally the pinnacle of design, requiring pattern recognition, dodge timing, and strategic Auxiliary use. The soundtrack here is legendary, a point we will revisit.

Flaws in the Fabric:

* Repetition: The core combat is fun, but fighting the same 5-6 grunt enemy types in the same 3-4 environmental templates for 15-20 hours breeds fatigue.

* Floatiness & Impact: Many reviews (RPGFan, cublikefoot) note combat lacks “weight.” Attacks don’t feel impactful; hitstun is minimal, leading to a “button-mashing” feel against bosses, especially on lower difficulties.

* Pacing & “Bloat”: The story-mission ratio is skewed. As The Gamer’s Lounge quipped, “For every minute spent in combat these girls spend three minutes talking about it.” The required dialogue to progress can feel like a chore.

* Accessibility: A critical failure. No meaningful difficulty options beyond an obscure “Casual Mode.” No text scaling, no audio cues for prompts, limited control remapping. This actively excludes a significant player base.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A schism between character and canvas

Visual & Art Design:

Crymachina presents a “schism of aesthetics.”

* Characters & Portraits: Universally lauded. The anime/manga-styled 2D portraits are incredibly expressive, detailed, and dripping with personality. The 3D models, while not at a AAA level, effectively translate this charm. The designs are iconic: Leben’s crimson and black, Mikoto’s punk-rock flair, Ami’s elegant dress, the grotesque, glitching Cherubim bosses. This is the game’s strongest visual suit.

* Environments: The Achilles’ heel. The “post-apocalyptic, sci-fi/futuristic” setting suffers from “drab, uninspired environmental design.” Corridors, metallic platforms, digitally-rendered gardens—they are functional but forgettable. The lack of environmental storytelling (decayed human artifacts, data-logs with context) makes Eden feel like a series of disconnected arenas rather than a lived-in, desperate ark. The “Garden of Imitation” hub is cozy but small. This is a massive missed opportunity; the setting’s potential is squandered.

Sound Design & Music:

This is the game’s unassailable triumph. Composed by Sakuzyo (known for artcore and rhythm games) with vocals by Hikaru Toono (voice of Enoa), the OST is an “aggressively melodic dreamscape.”

* The soundtrack masterfully blends glitchcore EDM, orchestral swells, and haunting vocaloids.

* Boss themes are show-stoppers, each a unique, frenetic composition that elevates the combat to a euphoric, time-dilating experience. The music doesn’t just accompany the action; it defines it.

* The Japanese voice acting, as noted, is exceptional, providing warmth and nuance that often elevates the prose. The sound effects are crisp, satisfying the “kinetic” feel of combat.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Anthem, Not a Mainstream Triumph

Critical Reception:

Metacritic shows a Metascore of 65 (PS5) based on reviews averaging a 70% on MobyGames. The spectrum is wide: from the ecstatic 90% (GameZebo, Digitally Downloaded) down to the scathing 40-50% (KeenGamer, Push Square, Finger Guns). The consensus splits along predictable lines:

* Praise focuses on: story ambition & themes, character chemistry & VA, combat customization & feel, soundtrack.

* Criticism targets: convoluted/poorly-delivered narrative, repetitive mission/level design, shallow/drab environments, floaty combat.

The game is consistently called a “strong foundation” or a “promising yet flawed” entry. It is almost universally compared to NieR:Automata (deemed less polished in combat but more “heartwarming” and direct), and to FuRyu’s own Crystar (a clear step forward in gameplay, but with similar narrative bloat).

Commercial & Player Reception:

Sales data is private, but its quick appearance in discount bins and on platforms like Steam ($38.99) suggests modest commercial performance. Player scores on Metacritic (~7.0) are slightly higher than critic averages, indicating a “niche cult appeal.” Those who connect with the characters and themes tend to overlook the repetition; those who don’t, see only the flaws.

Legacy & Influence:

Crymachina will not be remembered as a genre-defining masterpiece. Its legacy is likely that of a “cult favorite” and a “proof of concept.”

1. For FuRyu/Aquria: It solidifies their signature “philosophical action-RPG” brand. The combat improvements from Crystar are noted, but the repetition in structure suggests a need for a fundamental rethink in level/gameplay design for future projects.

2. For the Genre: It reinforces the viability of the ~20-hour, story-centric action RPG. However, its reception serves as a cautionary tale about “narrative bloat”—the danger of prioritizing philosophical volume over narrative clarity and pacing.

3. Thematically: It joins the conversation of “what is human?” in games, but its method of delivery (static scenes, acronym-heavy jargon) may limit its influence compared to the more integrated storytelling of NieR or Soma. Its direct treatment of “Cast Full of Gay” characters (Leben, Mikoto, Ami are all canonically lesbian/bi) is notable for its matter-of-fact inclusion in a mainstream JRPG.

Conclusion: A Faulty, Beating Heart

Crymachina is not a great game. Its repetitive mission structure, convoluted exposition, and environmental barrenness are substantial faults that cannot be ignored. It fails to translate its profound themes into a consistently engaging interactive experience. Yet, to dismiss it outright is to miss its undeniable, beating heart.

This is a game with “a big cybernetic heart.” Its successes are profound: a combat system that, for all its floatiness, offers deep customization and thrilling, fast-paced clashes set to a Top 10-tier video game soundtrack. It presents a cast of emotionally resonant, openly queer heroines whose found-family dynamic provides genuine warmth. Its central question—of whether synthetic beings can earn the right to be called human through love and pain—is handled with a sincerity that, when it breaks through the jargon, can be genuinely moving.

In the pantheon of video game history, Crymachina will occupy a specific, niche shelf. It is not NieR:Automata. It is not Xenoblade Chronicles. It is FuRyu’s own beast: an ambitious, messy, heartfelt, and stylish action RPG that reaches for the philosophical heights but stumbles on the practical ground. Its place is that of a curated experience for the patient, the philosophically inclined, and the emotionally receptive. For those willing to wade through the repetitive corridors and lore dumps, Crymachina offers a journey with flashes of brilliance, a soundtrack to remember for a lifetime, and a conclusion that, against all odds, may just bring a tear to your eye—the ultimate validation of its central, fragile thesis.

Final Verdict: Crymachina is a flawed gem. Its combat sparkles, its soundtrack soars, and its core emotional narrative has genuine power. However, these strengths are shackled by repetitive design, convoluted storytelling, and a failure to create a world worth exploring beyond its central characters. It is a game worth experiencing for its ambitions and its heart, but one must be prepared to forgive—or even skip—its mechanical and structural shortcomings. A solid 7/10—a game that inspires passion in both its defenders and its detractors, and a clear signpost for what FuRyu could achieve with a tighter rein on its own monumental ideas.