- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: 1C Company, FX Interactive, S.L., Haemimont Games AD, PAN Interactive, Snowball.ru, Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc., TalonSoft, Inc.

- Developer: Haemimont-Smartcom OOD

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: LAN, Online Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Base building, Campaign Editor, Day-night cycle, Diplomacy, Fog of war, Magic, Real-time strategy, Resource Management, Spies, Trade

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 75/100

Description

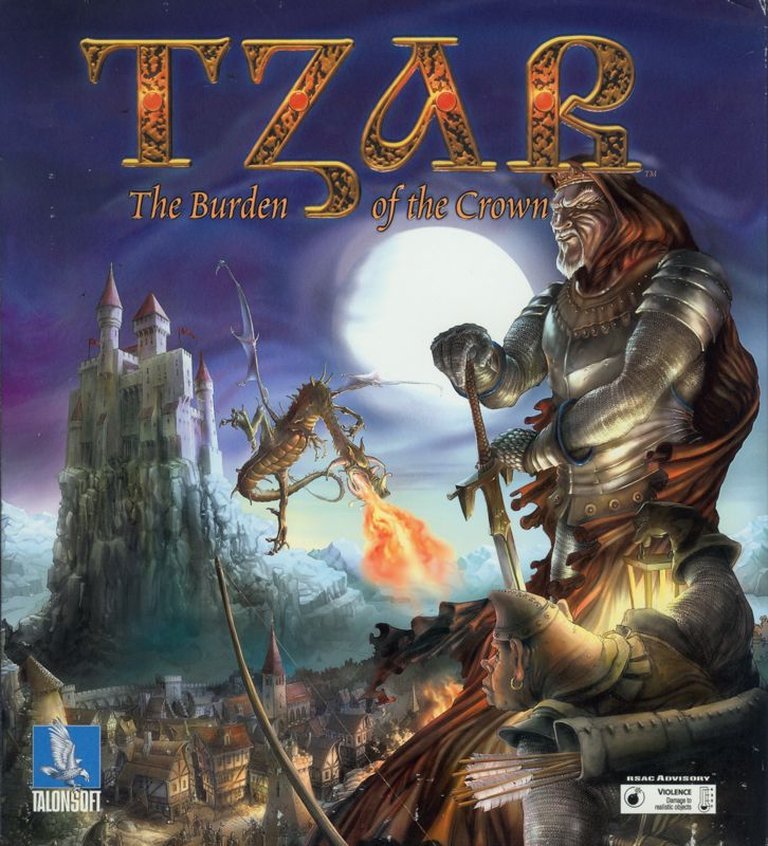

Tzar: The Burden of the Crown is a fantasy real-time strategy game set in a world divided among European, Asian, and Arabian races, where players take on the role of Sartor, a peasant discovered to be the royal heir, as he campaigns to reclaim his throne from the Army of Evil across multiple continents. Featuring a 20-mission campaign, text-only briefings, and gameplay similar to Warcraft II or Age of Kings, it includes multiplayer support, a mission editor, and fog of war mechanics.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Tzar: The Burden of the Crown

Tzar: The Burden of the Crown Free Download

Tzar: The Burden of the Crown Reviews & Reception

ign.com (69/100): Tzar falls short and feels too familiar to excel in its own right.

metacritic.com (82/100): While Tzar may have borrowed a great deal from other strategy games, it failed to inherit several of those games’ strategic amenities.

Tzar: The Burden of the Crown Cheats & Codes

PC

Press [ENTER] during gameplay to open the command box, then type the cheat code and press [ENTER] to activate. For multiplayer, first type hmprettypleasewithsugarontop to enable cheat mode.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| hmprettypleasewithsugarontop | Enables cheats in multiplayer games |

| hmdvaleva | Grants 10,000 of each resource |

| hmpetleva | Grants 50,000 of each resource |

| hmnotech | Enables all greyed/hidden technology buttons |

| hmcalc | Opens calculator; enter math expression to compute |

| hmtimer | Displays the game clock |

| hmshowgrid | Displays the map grid |

| hmreveal | Reveals the entire map |

| hmbuildozer | Toggles instant construction |

| hmresign | Player resigns from the game |

| hmnofog | Removes the fog of war |

| hmnext | Skips to the next level in campaign mode |

| hmgod | Makes selected units invulnerable |

| hmnopop | Sets population limit to 1000 |

| hmkingdom [number] | Changes the kingdom of selected units/buildings to player number (1-9) |

| hmspawn [class name] | Spawns an object of the specified class |

| hmhunt | Kills all animals on the map |

| hmusurp | Allows player to command enemy units/buildings regardless of owner |

| hmspy | Player sees through the selected units’ perspective |

| hmdiscover [tech class] | Discovers the specified technology |

| hmischeater | Checks if a player has used cheats |

| hmgive | Gives player 1000 gold |

| hmcont | Increases health of selected units by 5 |

| hmthreads | Displays map coordinates |

| hmmap | Displays the name of the current map |

| hmdemo | Starts the demo |

| hmtime [hour] | Sets the game time to the specified hour (1-20) |

| hmdebugpath | Clears path if slow and makes it regular |

Tzar: The Burden of the Crown: The Overlooked Masterpiece of Depth and Deception

Introduction: The Crown’s Heavy Burden

In the crowded pantheon of late-‘90s real-time strategy games, few titles sit in as curious a position as Haemimont Games’ Tzar: The Burden of the Crown. Released in early 2000 into a market saturated with the towering legacies of Age of Empires II and the imminent arrival of Warcraft III, Tzar arrived not with a revolutionary bang, but with the quiet confidence of a deeply meticulous craftsman. It was a game that, on the surface, wore its inspirations on its sleeve—so much so that it risked being dismissed as aclone. Yet, beneath that familiar facade lay a complex, interlocking system of strategic choices, character progression, and sorcerous power that dwarfed many of its contemporaries in sheer depth. This review argues that Tzar is not merely a competent imitation but a bold, if flawed, experiment in synthesizing the[RTS] genre with the persistent character growth of the[RPG]. It is a game of remarkable engineering brilliance and frustratingly uneven presentation, a sleeper hit whose burden was not its crown, but the weight of impossible expectations and the shadow of giants. Its legacy is that of a cult classic—a game revered by a small but devoted cohort who discovered its secrets, and a poignant “what if” for a genre eager to evolve.

Development History & Context: A Bulgarian Odyssey

Tzar was developed by Haemimont Games, a studio based in Sofia, Bulgaria, founded in 1993. At the turn of the millennium, Haemimont was a curious entity: a Eastern European developer with a clear Western sensibility, having previously worked on Codename: Eagle and Hidden & Dangerous. The project was led by designer Vesselin Handjiev and a core team of roughly 70 developers, as listed in the credits. Their vision, as articulated through the final product, was to create a fantasy medieval RTS that captured the tactical breadth of Age of Empires while injecting the long-term unit development and magical spectacle more commonly associated with hero-centric games like Heroes of Might and Magic or Warcraft III (which would launch later that same year).

The technological context was one of transition. The RTS genre was dominated by sprites and pre-rendered 2D graphics (Starcraft, Age of Empires II) or was on the cusp of a 3D revolution (Shogo: Mobile Armor Division, Homeworld). Haemimont chose a highly polished, detailed sprite-based engine operating at a fixed 800×600 (with an option for 1024×768). This was a deliberate, conservative choice that prioritized frame rate, unit count (reportedly up to 1,000 per side), and animation fluidity over cutting-edge 3D visuals. The constraints were clear: no hardware-accelerated 3D, limited cinematic capabilities, and a focus on gameplay complexity over graphical spectacle.

The gaming landscape of early 2000 was fiercely competitive. Microsoft’s Age of Empires II and its Conquerors expansion were the undisputed kings of historical RTS. Blizzard’s StarCraft defined the competitive esports scene. Warcraft III was on the horizon, promising to redefine the genre with its hero-focused model. Tzar was published in the West by TalonSoft, a company known for its historical wargames, and in various regions by 1C Company, FX Interactive, and others. Its release in January 2000 (EU) and March 2000 (NA) placed it in a critical window, ultimately leading to its being overshadowed. The game did, however, find a significant audience in Spain, reportedly reaching #1 on sales charts and achieving “Gold CDROM” status with 50,000 copies sold by November 2000, indicating a strong regional appeal that failed to translate globally.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Prophecy of Sartor

The campaign of Tzar is a sprawling, continent-hopping epic delivered almost exclusively through text-based mission briefings and in-game dialogue—a notable absence of voice acting or high-production cinematics that immediately dates the presentation but places narrative agency squarely on the writing. The story follows Prince Sartor of Keanor, the “son of a king” raised in obscurity as a lumberjack. After his village is raided and his uncle killed by the forces of the usurper Borgh, he is rescued by the white mage Ghiron and thrust into his destiny.

The plot is a classic good-versus-evil fantasy, but with a specific, cosmological structure. The evil is not merely a political rival but the “Messiah of Evil,” one of five primordial forces (the others being Greed, Treachery, Fear, and Indolence) unleashed by the theft of a sacred Crystal that once bound darkness. This elevates the conflict from a simple civil war to a literal battle for the world’s soul. Sartor’s journey is one of coalition-building. He must rally the three disparate cultures of Keanor—the Europeans (based on medieval Western knights), the Arabians (with Janissary and desert themes), and the Asians (drawing on Shaolin, ninja, and samurai motifs)—each with their own homelands, grievances, and heroic units.

Thematically, the game explores the “burden” of leadership. Sartor begins as a reluctant peasant and must physically and metaphorically rise through the ranks, a process mirrored by the gameplay’s unit-leveling system. The narrative structure is episodic: liberate your homeland, secure the capital, then embark on a diplomatic and military tour of distant continents to secure alliances, all culminating in a final, apocalyptic siege against the dark portal. The ending, as noted by player reviewer MAT, is deliberately open, hinting at the eternal nature of the struggle (“evil shall always remain”), and was clearly designed with sequel potential. While the writing is functional and lacks the cinematic flair of StarCraft, it effectively provides context for the sheer scale of the campaign’s 20 missions, justifying the shift from local skirmish to global crusade.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Guild of Choices

Tzar‘s core RTS loop is a familiar one: gather four resources (Food, Wood, Gold, Stone), build a base, train an army, and destroy the enemy. However, its genius lies in the profound strategic bifurcation introduced by the “Guild” system, a late-game (but pivotal) choice that defines a player’s entire approach. There are four elite Guild buildings, each prohibitively expensive, forcing the player to commit to one primary strategic path per game:

- The Warriors’ Guild (Way of Glory): This path focuses on martial prowess. It removes the level cap on units, allowing any soldier to gain experience through combat and reach a “Heroic” 12th level, gaining a unique name and stats. It also enables the research of faster experience gain and the hiring of mercenary squads directly from the Inn. This path favors the creation of a small, terrifyingly elite core army.

- The Mages’ Guild (Way of Magic): This path unlocks the creation of Wizards and a extensive spell tree. Each race has unique spells (e.g., Europeans summon bats/giants, Arabians summon genies, Asians summon dragons), but all provide devastating area-of-effect damage, making this a powerful counter to massed “war” armies. Wizards are fragile but become apocalyptic forces with the right spells.

- The Religious Guild (Cathedral/Mosque/Shaolin Monastery): This path produces Priests, who are the ultimate counter to magic. They have a long sight range to spot enemy Wizards and can neutralize them with a single shot. They also heal and bless friendly units. This path also grants access to elite religious units (Crusaders, Jihadi Warriors, Monks) and, crucially, Spies. Spies can infiltrate enemy bases by impersonating a peasant, allowing the player to see all enemy activities, collect resources, or even sabotage. This is one of the game’s most sophisticated and under-discussed features.

- The Merchant’s Guild (Way of Craft and Trade): This is the economic and naval path. It enables resource trading, gambling, and loans. Most importantly, it allows the population cap to be increased (more peasants) and unlocks elite War Galleons—powerful, long-range ships that dominate water maps. For Europeans and Arabians, it also unlocks the ability for peasants to bribe enemy units, a cheap and sneaky tactic to cripple an opponent’s army.

These paths are not mutually exclusive in building, but their cost makes choosing one or two a hard strategic decision. This creates a deep, paper-rock-scissors dynamic: Magic beats War (area spells), Religion beats Magic (priest sniper), War beats Religion (overwhelming numbers), and Trade can support any with economy or disrupt enemies with bribes/spies.

Other Notable Systems:

* Universal Unit Leveling: Every non-siege unit (including peasants) gains experience and levels up, a full year before Warcraft III. This makes individual units valuable assets. A 12th-level knight is an army unto himself.

* Magic Items & Artefacts: Scattered across maps are weapons, armor, spellbooks, and potions that can be picked up by units, further enhancing them. This adds an exploration and scavenging element.

* Faction Distinction: While early units are similar, each culture has unique units (Ninja, Janissary, Crusader), unique monsters (Dragons vs. Genies vs. Stone Golems), and different architectural styles. The Arabian “Instant Militia” (converting peasants to Jihadi Warriors) is a famous early-game rush tactic.

* Campaign Structure: The 20-mission campaign is praised for its escalating scale but criticized for a slow introduction of the guild system. Players must survive “old school” RTS missions before unlocking the game’s defining strategic layer.

* Flaws: The user interface and unit control are significant detractors. As noted in the My Abandonware review and TV Tropes, units do not cluster when grouped and moved; they retain spacing, making regroupi ng a tedious manual process. Pathfinding for large units (siege engines, golems) around trees is notoriously poor. Garrisoning is clumsy. The learning curve is steep, exacerbated by a poor manual that fails to explain unit bonuses and roles.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Polished, If Dated, Fantasy

The world of Keanor is a generic but effective fantasy-medieval patchwork. The three cultures are pastiche but visually distinct: Europeans have castles and plate armor, Arabians have domed architecture and curved blades, Asians have pagodas and lacquered armor. The sprite work, while 2D and fundamentally of its era, is frequently praised for its detail and animation quality. One user reviewer, “Hollyoake Addams,” states unequivocally: “this games sprites are actually the best i’ve ever seen in an RTS. Much better than CNC Red Alert and Warcraft 2.” The unit animations for combat, casting, and movement are fluid, and spell effects (like the ice shaft of the Freeze spell) have a satisfying visceral impact. The art direction, while not groundbreaking, is cohesive and colorful.

The sound design is a highlight. The soundtrack, composed by Kiril Petrushev and Dimitar Sabev, is described as evocative and memorable, with one reviewer noting they had it memorized. It uses a medieval-inspired palette with ethnic flourishes matching each culture. Sound effects for combat, magic, and the environment (thunder, rain) are clear and impactful. The day-night cycle is not merely cosmetic; it genuinely affects gameplay, reducing vision range at night and making stealth and ambush viable, changing the tempo of play every 30 in-game minutes.

The presentation’s greatest weakness is the lack of voice acting and cinematic cutscenes. Mission briefings are text-only, and the intro animation is widely derided as cheap and dated (the “MAT” review calls it “worst then if it was done like 15 years ago”). This creates a barrier to immersion that the solid gameplay and world map struggle to overcome. When compared to the cinematic storytelling of StarCraft released two years prior, Tzar feels narratively thin, despite its epic plot.

Reception & Legacy: The Cult of the Underdog

Tzar received average to slightly above-average reviews at launch, with critic scores hovering around 70-74% (MobyGames 74%, GameRankings 69%). The split in critical opinion is telling:

* Praise focused on its staggering depth, strategic flexibility, robust multiplayer (noted for its stability and “never disconnect” reliability by user MAT), innovative unit progression, and the cunning AI that reportedly “pretends to be stupid” to lure players into traps.

* Criticism centered on its lack of originality (“just an Age of Empires clone” – Eurogamer’s 6/10), poor unit pathfinding and control, unintuitive interface, and the late arrival of its best features in the campaign. IGN’s 6.9/10 review succinctly capped it: “this game has everything in place with nothing spectacular.”

Its commercial performance was modest but regionally successful, notably in Spain. It never achieved the mainstream breakthrough of its peers and was largely forgotten by the broader gaming public after 2001. However, it has undergone a significant rehabilitation via re-releases and cult appeal. On Steam, it holds a “Very Positive” rating (90% of 509 reviews) as of 2025. Modern user reviews consistently praise its depth, stability, and unique mechanics, with many lamenting that modern RTS games lack its intricate systems.

Legacy and Influence:

1. The “Full Experience” RTS Prototype: Tzar‘s most significant legacy may be its full implementation of universal unit leveling—a system that would become a staple in the genre via Warcraft III‘s hero model but was executed here with democratic breadth (any unit can become a hero).

2. Haemimont’s Path: The studio leveraged Tzar‘s foundational work in deep RTS mechanics and fantasy world-building to create the well-received Rising Kingdoms (2003) and later transition successfully to city-building (Glory of the Roman Empire) and the acclaimed Tropico series. The DNA of Tzar—complex systems over flashy graphics—informed their later successes.

3. The Cult Classic Blueprint: It stands as a case study in a game whose quality is inversely proportional to its marketing and timing. Its rediscovery on GOG (2013) and Steam introduced it to a new generation of RTS historians who value mechanical depth over franchise pedigree.

4. A Missed Crossroads: Had it been released a year earlier or with stronger production values, it might have been cited as a peer to Age of Empires II rather than a derivative. Its combination of RTS base-building, RPG-like unit progression, and espionage was years ahead of its time in integration.

Conclusion: A Crown Earned Through Endurance

Tzar: The Burden of the Crown is not a perfect game. Its interface can be clunky, its pathfinding frustrating, and its story told with all the drama of a spreadsheet. It arrived at the wrong time, wearing the wrong clothes, and was judged by a public hungry for the next big thing. Yet, to dismiss it is to miss one of the most mechanically rich and strategically rewarding RTS experiences of its era.

Its genius is in its systems over spectacle philosophy. The Guild choice is a masterstroke of forced specialization. The universal unit leveling creates an emotional attachment to a pecking-order army that few RTS have matched. The Spy mechanic introduces a layer of psychological warfare and information control that remains rare in the genre. The AI, as celebrated by its fans, plays a long, cunning game.

For the professional historian, Tzar is a fascinating artifact: a Bulgarian studio’s ambitious attempt to synthesize the best design philosophies of Western RTS and RPG into a single, coherent whole. It is a game that asks much of its player—patience to learn its systems, tolerance for its dated presentation—and rewards that investment with a depth and emergent storytelling that few of its flashier contemporaries could offer.

Final Verdict: Tzar: The Burden of the Crown is a flawed masterpiece, a sleeping giant of the RTS genre. It earns its crown not through royal decree or genre revolution, but through sheer, unyielding mechanical complexity and a vision that saw the future of the genre—persistent unit identity and deep strategic choice—more clearly than many of its contemporaries. It belongs in the tier of “essential cult studies” alongside Kohan: Immortal Sovereigns and The Lord of the Rings: The Battle for Middle-earth. To play Tzar is to undertake a burden, but one that ultimately reveals a kingdom of strategic delight few other games of its time could match. It is a testament to the idea that the heaviest crowns—the deepest games—are often the ones forged in relative obscurity.