- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: DreamCatcher Interactive Inc.

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Single-player

Description

Missing: Game of the Year Edition is a special compilation that includes the base game Missing, its expansion The 13th Victim, and a behind-the-scenes disc, providing a mature-rated experience centered around mystery and investigative gameplay.

Missing: Game of the Year Edition Reviews & Reception

retro-replay.com : This all-in-one package promises hours of suspenseful gameplay and bonus content that fans and collectors will treasure.

Missing: Game of the Year Edition: A Cult Classic’s Flawed, Fascinating Descent into Digital Murder

Introduction: The Ghost in the Machine

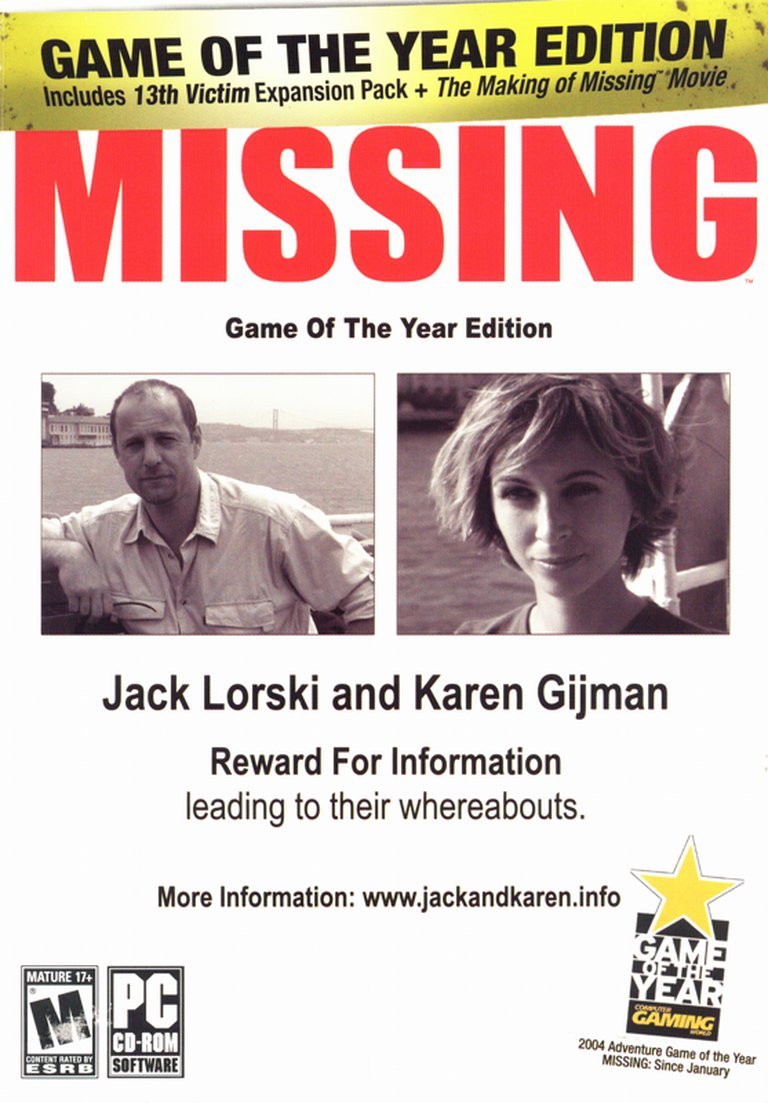

Long before alternate reality games (ARGs) became a niche marketing strategy and “immersive” thrillers relied on smartphone notifications, there was Missing. A title that remains stubbornly, intriguingly obscure—a footnote in adventure game history that dared to merge the mundane reality of the early-2000s internet with the visceral horror of a serial killer’s mind. The Game of the Year Edition, released in 2005 by DreamCatcher Interactive, is not a traditional “Game of the Year” celebration but a pragmatic compilation: it bundles the original 2003/2004 title (released in Europe as In Memoriam), its 2004 expansion The 13th Victim, and a behind-the-scenes disc into a single physical package. This review argues that Missing is a profound and prescient failure—a game whose visionary core concept of “playing along” with a murderer through real websites and in-game emails was perpetually undermined by clunky arcade puzzles, technical roughness, and a narrative that collapses under the weight of its own ambition. Yet, its audacity to weaponize the player’s own desktop as a haunted space marks it as a crucial, if flawed, ancestor to modern narrative design and analog horror. To play Missing is to witness a studio, Lexis Numérique, staring into the abyss of interactive storytelling and blinking first, but not before leaving an indelible, chilling fingerprint on the medium.

Development History & Context: From Children’s Apps to Serial Killers

The game emerged from the mind of French developer Éric Viennot and his studio, Lexis Numérique. Prior to Missing, Viennot was known for the Uncle Albert series, innovative children’s edutainment titles that used interactive, animated pages to teach and entertain. This background is critical: Viennot was fascinated by interactive media’s potential to create situations rather than just puzzles, but the jump from a whimsical, bug-catching interface to a grim, adult thriller about a sadistic killer codenamed “The Phoenix” was a seismic shift in tone and target audience.

Missing arrived in a very specific technological and cultural moment. The year 2003/2004 was the tail end of the “dot-com boom” mindset, where the internet was still wondrous and slightly untamed for many users. It was also the era of experimental “web-centric” games like Majestic (EA’s subscription-based ARG with real phone calls) and the A.I. Artificial Intelligence movie tie-in game, which used real websites as part of its puzzle hunt. Missing positioned itself within this vanguard, promising a thriller that could not exist without a live internet connection. However, it was constrained by the technology of the time: dial-up was still common, browser security was primitive, and the idea of a game deeply integrating with a player’s personal email account was both revolutionary and fraught with privacy and stability concerns.

Publishing was handled by The Adventure Company in North America and later DreamCatcher Interactive for the Game of the Year Edition. This placed it within the “adventure game revival” movement of the early 2000s, a period seeing a resurgence of point-and-click titles from companies like Adventure Soft and Cryo Interactive. However, Missing was an outlier—less a classic inventory-puzzle adventure and more a “media investigation simulator,” placing it in a genre all its own, one that would not see many successors.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Voyeur’s Pact with Evil

At its heart, Missing is a story about complicity. You are not a traditional protagonist like a detective or a hero. You are an unnamed, faceless “player” who receives the first email: journalists Jack Lorski and Karen Gijman have vanished while investigating a series of murders. Their last transmission was a cryptic message containing the game’s starting website. You are immediately recruited—or coerced—into continuing their work by communicating with the murderer himself, The Phoenix, via email and by navigating the web of clues he leaves behind.

The Plot’s Architecture: The narrative is delivered in fragmented, non-linear bursts. Progress is gated by solving puzzles on specially created, diegetic websites (like a mock software company or a twisted art portfolio). Successfully completing a puzzle yields a “reward”: a piece of video footage. This footage is the game’s true narrative engine, split into two distinct visual languages:

1. The Journalists’ Footage (Color, 35mm-style): These are short, intimate, beautifully shot scenes depicting Jack and Karen’s relationship and their investigation into the Phoenix’s past murders, starting with the killing of Karen’s father. They ground the story in human emotion and a sense of tragic pursuit.

2. The Phoenix’s Footage (Black & White, Handheld 8mm): This is the horror. Grainy, shaky, and terrifyingly intimate, these clips show the Phoenix’s perspective—his preparations, his rituals, his victims. The aesthetic is deliberately reminiscent of real snuff film or police evidence reels, designed to make the player feel like a co-conspirator watching a murder unfold.

Themes of Mediated Violence and Archival Fascination: Missing brilliantly explores how modern society consumes violence through screens. You, the player, must watch these horrific clips to progress. The game forces you into the role of an archivist of atrocity, clicking “next” to see more. The Phoenix’s taunting emails, which occasionally arrive in your real inbox, break the fourth wall in a genuinely unsettling way, blurring the line between game space and personal space. The central theme is one of inherited trauma: the Phoenix’s murders are a direct, obsessive response to a past crime (Karen’s father’s murder), suggesting a cycle of violence that the player’s investigation literally perpetuates.

The Abrupt, Divisive Conclusion: The game’s ending is famously sudden and philosophically open to interpretation. Without spoiling, it denies the player a cathartic confrontation or a clear resolution. Instead, it offers a moment of quiet horror and implication, leaving the true nature of the Phoenix—a monster, a corrupted soul, or something else—and the player’s own role in his narrative haunting. This rejection of traditional closure is thematically consistent but notoriously unsatisfying, a point of sharp criticism in the GameBoomers review, which describes feeling “ripped off” yet later haunted by the “cryptic madman and his legacy.”

Flawed Characterizations: While the performances (particularly Jack’s actor/narrator) are praised for their credibility, the characters exist primarily as vessels for plot or as talking heads in FMV sequences. You never truly interact with them in a meaningful dialogue tree; their value is as providers of the next story fragment. This reinforces your position as an external observer, not an active agent within the story’s social world.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A House of Cards Built on Shifting Sands

This is where Missing’s grand experiment most visibly fractures.

Core Loop: Investigate a website → solve a puzzle (often a mini-game) → receive an email with a password/code → unlock a video file → receive next website/target. The loop is inherently passive and directionless at times, relying heavily on the player’s own curiosity and willingness to “surf” the provided (and sometimes real, though this element is often broken) internet.

Puzzle Design Dichotomy: The GameBoomers review perfectly captures the致命 flaw: a schism between brilliant, devious logic puzzles and frustrating, arbitrary arcade twitch challenges.

* The Good: Some puzzles are brilliant integrations of theme. You might need to decipher an audio file from a crime scene, reconstruct a shredded document, or interpret symbolic artwork. These feel like genuine detective work.

* The Bad (The “Pac-Man Clones”): Many gatekeeping puzzles are simplistic arcade games: navigate a maze while avoiding drones, catch falling items, etc. These are pure mechanical hurdles with zero narrative justification. Their difficulty often spikes arbitrarily, and their failure state is brutally punitive. As the reviewer states, if you fail, you must restart the entire puzzle sequence from the beginning due to the game’s infamous single, auto-saved checkpoint system. This transforms a narrative thriller into a punishment simulator, utterly destroying tension and immersion.

The Email & Internet Integration: This was the revolutionary promise. The game instructs you to use a personal (or new) email account. Characters (assistants, the Phoenix) send messages. However, as the reviewer notes, this feature is spectacularly underutilized. The emails are mostly passive notifications or one-off tool deliveries. There is no ability to reply or engage in dialogue. The potential for a dynamic, responsive narrative through email was completely squandered, leaving the feature feeling like a gimmick that occasionally delivered a needed clue but mostly cluttered an inbox. The Phoenix’s single, personalized taunting email is the lone exception that proves the rule—it worked brilliantly because it broke the pattern of useless NPC communiqués.

Interface & UI: The interface is functional but dated. You click your way through websites and mini-games. The “tool” for solving puzzles (like a code decoder or audio analyzer) is often a separate, clunky application launched from the game’s UI. It feels like a series of loosely connected DOS programs rather than a cohesive whole.

Technical Glitches: The GameBoomers review provides a crucial cautionary tale. The in-game web browser/search engine was notoriously unstable and hardware-dependent. The reviewer was unable to get it to function consistently on their (Presumably standard for 2004/2005) system (Pentium 4, 2.6 GHz, GeForce 5200), resorting to patches, alternate installations of the European version (In Memoriam), and provided solve codes just to progress. This level of fundamental instability is a death knell for any game that relies on seamless internet simulation; it constantly yanks the player out of the experience with crashes and errors, reminding them it is “just a buggy game,” not a sinister online hunt.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Masterful Atmosphere, Imperfect Execution

Missing’s greatest triumph is its aesthetic of dread. The world is not a fantastical realm but the recognizable, mundane internet of the early 2000s—a place of static HTML, garish Geocities-esque backgrounds, and raw, unpolished design. This verisimilitude is its power. The “fake” websites created for the game (the Phoenix’s lair, a dead-end forum) are convincing because they mimic the amateurish, personal nature of the early web. The atmosphere is thick with analog horror tropes: glitchy .gifs, cryptic text appearing letter-by-letter, distorted audio clips, and that ever-present, chilling score.

FMV & Cinematography: The live-action footage is the game’s emotional core. The “journalist” footage is well-lit and professional, creating a baseline of normalcy. The Phoenix’s 8mm footage is where the artistry lies. The grainy black-and-white, the unstable camera, the muffled sounds—it feels like a genuine artifact of a deranged mind. The low-light cinematography and tight close-ups on actors’ faces (for clues) maintain a pervasive unease. While dated by modern standards, the practical effects and deliberate lo-fi quality have aged into a potent, documentary-style horror.

Sound Design: The score is minimal but effective, often consisting of droning, atonal strings or eerie ambient noise that swells during clue revelations. The sound of a dial-up modem connecting, the click of a mouse, the clack of a keyboard—these diegetic sounds are used sparingly but effectively to ground the player in the act of “hacking” the killer’s mind. The voice acting, as noted, is generally high-caliber, selling the realism of Jack’s narration and the Phoenix’s chilling, calm menace in his emails and voicemail messages (a feature mentioned in some documentation).

The Setting: There is no traditional “world” to explore—a mansion, a city. The setting is the player’s own desktop and browser. This is the game’s most innovative and terrifying concept: the monster is in your machine, on your screen, in your email. The “world-building” is the construction of a credible, invasive digital footprint for a fictional serial killer.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Artifact, Not a Classic

Contemporary Reception: Data is scarce. MobyGames records a single critic review (GameZone, 87/100, calling it a “fantastic title” and “must-get”), but this seems like an outlier or possibly for a different version. The provided Amazon and eBay listings show minimal activity, and Metacritic has no scores. The detailed GameBoomers review (2004) is emblematic of the polarized response: praise for its ambition, FMV, and atmosphere (graded “A”) but severe condemnation of its gameplay, interface, and instability (“D”). The overall grade of “C” or 75% reflects a game respected for its ideas but not loved for its execution. The Game of the Year Edition itself (2005) was likely a last-ditch commercial effort by DreamCatcher to recoup costs on a niche title.

Commercial Performance: It was not a mainstream success. Its requirement for a constant internet connection (for puzzle websites and emails) in an era of spotty connectivity and privacy fears was a major barrier. The technical issues and frustrating gameplay likely limited its audience to hardcore adventure fans and those specifically intrigued by its ARG-like premise. Its presence on MobyGames with only 7 collectors underscores its obscurity.

Influence & Legacy: Missing’s true legacy is as a cautionary tale and a prototype. It demonstrated the potent horror of violating the player’s personal digital space—a concept later evolution in the “haunted device” subgenre of horror games (e.g., Doki Doki Literature Club!’s file manipulation, .hack//’s fictional MMORPG, and even the “paranormal” YouTube spoof genre). Its structure of “solve puzzle, get video” is a direct predecessor to the compelling evidence-gathering loops of later investigative games like Her Story (2015), which perfected the non-linear FMV search mechanic without the extraneous mini-game baggage.

However, its failure to create a truly responsive narrative through email, its reliance on punishing mini-games, and its technical fragility made it a dead end for direct successors. It is studied more as an ambitious curiosity than as a foundational text. In academic discussions of “immersive” or “transmedia” gaming, Missing (or its original title In Memoriam) is often cited as a key early experiment in blending real-world tools with fictional narratives, a bridge between the static adventure game and the dynamic ARG.

Conclusion: The Verdict on a Digital Haunting

Missing: Game of the Year Edition is not a game to play for simple enjoyment. It is an experience to be analyzed and, at times, endured. Its place in video game history is secure not because it was well-made or successful, but because it attempted something radical and deeply unsettling: to make the player complicit in a horror story by using the tools of their everyday digital life.

The compilation itself is a serviceable collector’s item for the historically curious, bundling the complete story with intriguing making-of material. But to engage with the base game is to confront a fractured masterpiece. The FMV sequences and atmospheric web design are hauntingly effective, creating a pervasive sense of dread that lingers. The narrative’s thematic sophistication about media, violence, and obsession is significantly ahead of its time.

Yet, this sophistication is constantly undercut by gameplay that is at best tedious (the irrelevant arcade mini-games) and at worst infuriating (the brutal checkpointing and technical instability). The revolutionary email system is a wasted opportunity. The ending, while thematically bold, refuses the player the satisfaction they are conditioned to expect.

Final Verdict: Missing: Game of the Year Edition earns a qualified recommendation as a vital historical artifact and a case study in over-reach. For students of game design, narrative, and horror, it is essential—a flawed blueprint that illuminated both the terrifying potential and the practical pitfalls of true digital immersion. For the modern player seeking a satisfying adventure game, it is a frustrating, often broken relic. Its genius is in its concept; its failure is in its execution. It is a game that deserves to be remembered, examined, and learned from, but not necessarily replayed. Its true “game of the year” status lies in its haunting afterimage—the feeling that the ghost in the machine was never really in the game at all, but in the player’s own willingness to keep clicking, keep searching, and keep watching the horror unfold on their screen.