- Release Year: 2008

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Tandem Verlag GmbH, Tivola Publishing GmbH

- Genre: Action, Puzzle

- Gameplay: Mini-games

- Average Score: 40/100

Description

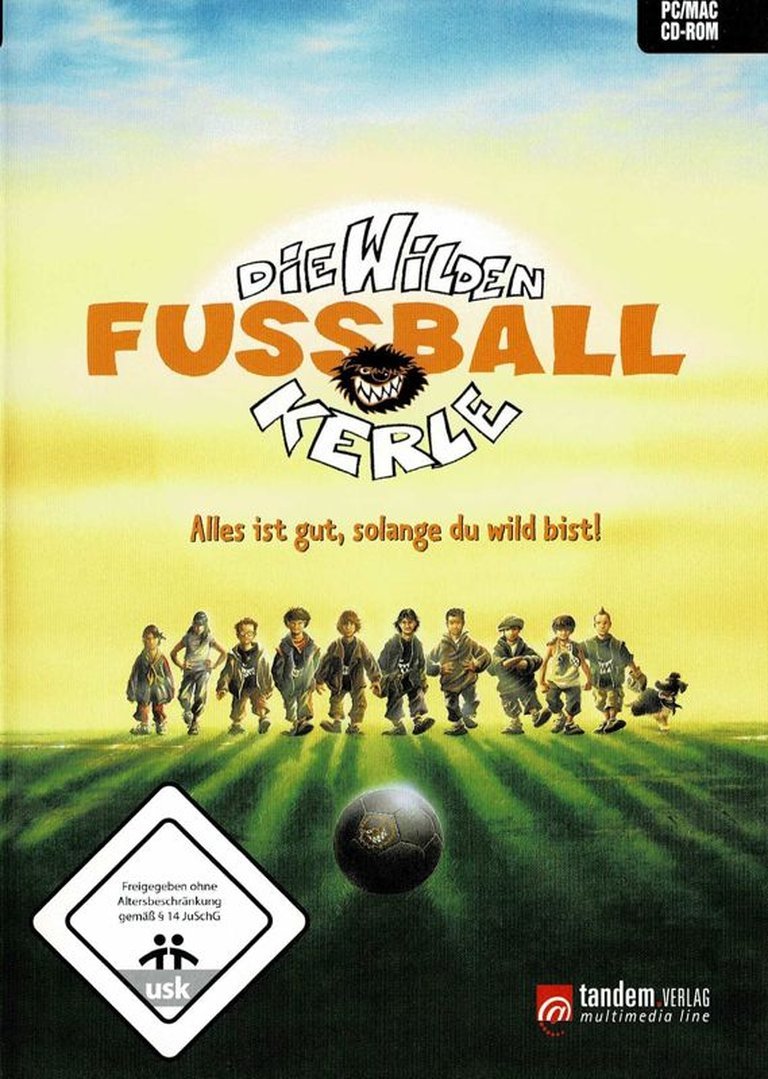

Die wilden Fussballkerle: Alles ist gut, solange du wild bist! is a 2008 video game adaptation of the German children’s book series, released for Windows and Macintosh. It centers on a variety of skill-based mini-games that embody the playful, adventurous spirit of the original stories, providing accessible and engaging challenges suitable for all ages.

Die wilden Fussballkerle: Alles ist gut, solange du wild bist! Reviews & Reception

imdb.com (40/100): I thoroughly enjoyed this movie.

Die wilden Fussballkerle: Alles ist gut, solange du wild bist!: Review

Introduction: A Cultural Artifact Disguised as a Game

In the vast, often-overlooked archives of European children’s interactive media, few titles capture a specific regional zeitgeist with such unadulterated, chaotic sincerity as Die wilden Fussballkerle: Alles ist gut, solange du wild bist! (The Wild Soccer Guys: All Is Well, So Long as You Are Wild!). Released in 2008 for Windows and Macintosh by Tandem Verlag GmbH and Tivola Publishing GmbH, this game is not merely an adaptation—it is a digital extension of a full-blown German multimedia phenomenon. Born from the mind of Joachim Masannek, the franchise began as a response to what he saw as overly rigid youth football coaching, evolving into a beloved book series, a successful 2003 film (grossing over $5 million worldwide), and a cascade of spin-off games. This review will argue that while the game itself is a technically simplistic and critically obscure collection of mini-games, its true value lies in its role as a pristine, playable time capsule of a specific moment in German family entertainment—a moment defined by rebellion, dirt, and the mantra that “Alles ist gut, solange du wild bist!”

1. Development History & Context: From Pitch to PC

The Genesis of a “Wilde” Universe: The entire “Wilden Kerle” franchise originated not in a corporate boardroom, but on a literal football pitch. Dissatisfied with the technical, joyless instruction in children’s football clubs, Joachim Masannek founded his own casual “little league” team for his sons and their friends in the late 1990s. He coached them with an emphasis on creativity, camaraderie, and getting gloriously dirty. The real-life adventures of this team, which included future actors like Raban Bieling and the sons of stars Uwe Ochsenknecht and Rufus Beck, directly inspired the characters and stories. The 2003 film, directed and written by Masannek, was a natural extension, featuring many of the original “Wilden Kerle” in the lead roles.

The Game’s Place in the Ecosystem: The video game arrived in 2008, five years after the film’s cinematic debut and amidst a thriving franchise. MobyGames data reveals this was not an isolated title but part of a coordinated multimedia push. Preceding games include Abenteuer in den Graffitiburgen (2004) and Entscheidung im Teufelstopf (2006) for Game Boy Advance, with a “Sammeledition” (Collected Edition) following in 2007. This 2008 Windows/Mac release appears to be a standalone or slightly enhanced iteration of that core concept. The publishers, Tandem Verlag and Tivola, were significant players in the German “edutainment” and licensed children’s software market, known for producing accessible, often low-budget, but faithfully adapted games for young audiences.

Technological Constraints & Market Landscape: The game’s specified system requirements—”Pentium II 300, 32 MB RAM, Win 95/98/ME/2000/XP”—place it firmly in the era of late-90s/early-2000s technology being repurposed for the mid-to-late 2000s budget software market. This was a period where CD-ROM was still the dominant media type for such titles. The game’s genre classification as “Action, Puzzle” with “Gameplay: Minigames” is a telling indicator. In an era increasingly dominated by 3D open worlds and online connectivity, Die wilden Fussballkerle represents a deliberate retreat to the simplicity of the “playground in a box” philosophy: a series of discrete, skill-based challenges requiring no complex save states or lengthy commitments. Its existence alongside more sophisticated titles highlights a persistent, underserved market for low-cost, high-familiarity, offline games for children—a niche often filled by licensed tie-ins.

2. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: More Than Just a Match

While the game itself is light on linear narrative, its entire impetus is drawn from the rich, recurring story world established by the film and books. Understanding this context is essential to analyzing the game’s scenarios.

The Canonical Plot (The Siege of the Teufelstopf): As detailed on film.at and IMDb, the core narrative centers on the “Wilden Kerle,” a self-proclaimed “best football team in the world” consisting of boys aged roughly 6 to 10. Their sanctum is “Camelot,” a three-story treehouse, and their cathedral is the “Teufelstopf” (roughly, “Devil’s Pit”), their beloved neighborhood football pitch. Their idyllic, dirt-streaked freedom is shattered by two calamities: 1) A bout of “sintflutartige Regenfälle” (flood-like rains) destroys the pitch, and 2) a rival gang of hooliganistic 13-year-olds, the “Unbesiegbaren Sieger” (Unbeatable Winners), led by the corpulent “Dicker Michi” (Fat/Fatty Mike), occupies the Teufelstopf. A pact is made: a winner-takes-all football match in ten days decides the pitch’s fate.

Themes of Anarchic Freedom vs. Institutional Authority: This is the franchise’s central, resonant conflict. The “Wilden Kerle” represent a Rousseau-ian state of natural childhood: their universe operates on their own slang (“Hottentottenalptraumnacht!”—a made-up exclamation of despair), their own rules, and a profound disrespect for adult structures. Parents are figures of punitive authority (“fünf wutentbrannte Elternpaare verhängen Fußballverbot und Hausarrest” – five furious parent couples impose football bans and house arrest). The film’s director, Masannek, explicitly positioned the work against what he saw as the soulless discipline of formal sports clubs. The game, therefore, is not about scoring goals against a generic AI; it is an interactive enactment of this rebellion. The mini-games are the “training” and “skirmishes” the kids would have undertake in defiance of their house arrest and to prepare for the climactic match against Michi’s team.

Character Archetypes as Game Avatars: The game allows players to embody the team’s key members, each with a defined, almost cartoonish persona from the source material:

* Leon (der Slalomdribbler): The charismatic leader, the “slalom dribbler.” His gameplay likely involves agility and ball control.

* Fabi (der schnellste Rechtsaußen der Welt): “The fastest right-winger in the world.” Speed-based challenges.

* Marlon (die Nummer 10): The star playmaker, “Number 10.”

* Maxi (‘Tippkick’ Maximilian): The silent, deadly finisher who “never talks.”

* Raban (der Held): “The hero,” but with “the big mouth”—brash and loud.

* Juli (die Viererkette): “The back four,” representing defensive solidity.

* Joschka (die siebte Kavallerie): “The seventh cavalry,” the wildcard, the surprise weapon.

* Vanessa: The disruptive, cool element—”ein Mädchen taucht auf!!” (a girl appears!!). Her inclusion, noted as a “catastrophe” in the film’s plot, would be a pivotal mini-game scenario, likely involving social navigation or a mixed-gender challenge.

The game’s title, Alles ist gut, solange du wild bist!, is itself a core thematic thesis. “Wild” here means authentic, free, messy, and un-corporatized. The game’s scenarios are therefore less about “football simulation” and more about performing this “wildness” through skill-based, often messy, defiance.

3. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Ten-Day Training Regimen

The eBay product description provides the most concrete, invaluable glimpse into the game’s actual play, listing specific mini-games. This forms the backbone of our mechanical analysis.

The Mini-Game Anthology Structure: The game eschews a single, cohesive engine for a “skill-game” compilation. The player’s journey likely involves selecting a character and cycling through different challenges that mirror the team’s ten-day prep period. This structure was common for licensed children’s games of the era, maximizing perceived value through quantity and variety while minimizing developmental complexity.

Deconstructed Mini-Games (Based on eBay Listing):

1. “Wild’n kick!” ( Fußball-Jump-and-Run): This suggests a side-scrolling or isometric platformer where the player dribbles/jumps a ball through an obstacle course. The “wild” modifier implies chaotic, physics-defying controls or environmental hazards (mud, broken glass, rival kids trying to tackle you). It’s a test of ball control under pressure, directly simulating the team’s genius “Ballkunststücke” (ball tricks) mentioned in the film synopsis.

2. “Ausbüxen-Spiel” (The Bust-Out Game): This is a brilliant thematic translation. “Ausbüxen” is German children’s slang for “to bunk off” or “to escape.” The plot’s house arrest (“Hausarrest”) is a major early barrier. This mini-game is almost certainly a stealth or puzzle challenge where the player must sneak out of their bedroom/house without being caught by parents. It operationalizes the film’s narrative conflict into a tense, personal challenge of wit vs. authority.

3. “Wer kann den Ball am längsten in der Luft halten?” (Who can keep the ball in the air the longest?): A classic, pure skill trial. Likely a simple click/keypress timing game to juggle the ball. It emphasizes individual mastery and showmanship—core “wild kerle” values.

4. “Druckerei” (Print Shop): This is a fascinating outlier. It suggests a creative, non-competitive activity where players can design posters, team rosters, or maybe even their own “wild” slogans and crests. This functions as a palate cleanser and a way to extend the game’s longevity through creation, tapping into the franchise’s graffiti and self-expression aesthetic (hinted at in the title Abenteuer in den Graffitiburgen).

5. Interviews mit den Filmkindern (Interviews with the film children): This is not a game but a multimedia feature. It reveals the publisher’s intent to blur the lines between the film’s actors and their characters, offering behind-the-scenes content to deepen fan engagement. For a child player, this was a premium feature, creating a direct connection to the “real” Wilden Kerle.

Overall Systems Analysis: There is no evidence of a persistent character progression system (leveling up stats). The “progression” is likely unlocking new mini-games or areas as the in-game ten-day countdown progresses. The UI would be extremely simple, using large, colorful buttons and icons, targeted at a pre-literate or early-reading audience (USK rating 0, “ohne Altersbeschränkung” – without age restriction). The control schemes would be keyboard-only (likely arrow keys + spacebar) or simplistic mouse interactions, respecting the specified minimal system requirements. The core innovation, if any, is in the thematic integration of the mini-games. They are not random (like a standard Mario Party set) but are direct, diegetic recreations of the challenges the characters face within their own story. The house arrest game is the story; the ball-juggling is their secret practice.

4. World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetic of Rebellion

Visual Identity: The game’s box art (implied by eBay listings) and in-game graphics would be directly sourced from the 2003 film’s live-action aesthetic. Expect digitized photographs or cel-shaded renderings of the child actors (Jimi Blue Ochsenknecht as Leon, Raban Bieling as Raban, etc.) against the gritty, overgrown backdrop of the “Teufelstopf.” The art direction is crucial: it must communicate dirt. Grass stains, torn clothes, mud on faces, scuffed footballs. This is the anti-Kinder Überraschungseier (anti-Kinder Surprise Egg) aesthetic; cleanliness is the enemy. The “Graffitiburgen” (graffiti castles) from another title in the series suggest vibrant, street-art-inspired level backgrounds, a visual metaphor for the kids’ claim on their urban environment.

Sound Design & Iconic Score: The IMDb entry for the film lists “Bananafishbones” as the performers of the iconic song “Ich hasse dich schrecklich” (I hate you terribly), a track that became synonymous with the franchise’s blend of punk-ish energy and juvenile angst. It is virtually certain this song, and others from the film’s soundtrack by Gerd Wilden, feature prominently in the game. The sound design would be functional and punchy: the thwack of a well-struck ball, the splash of mud, the exaggerated clatter of a house arrest escape, and the signature battle cry of the team—”RAAAAAAAA!!!!!!”—as heard in the film synopsis. The audio palette is less about immersive orchestration and more about providing immediate, satisfying feedback for each mini-game action, reinforcing the “wild” and energetic tone.

Atmosphere & Setting: The game’s atmosphere is one of constrained chaos. The settings are hyper-specific: the indoor prison-like bedrooms during house arrest, the overgrown and muddy Teufelstopf, the secret treehouse fortress Camelot. This is not a vast open world but a intimate, chemically balanced ecosystem of permission and transgression. The player’s emotional journey is not one of epic scale but of localized, intense victories—escaping the house, winning a one-on-one dribble challenge, finally keeping the ball aloft for 100 juggles. The atmosphere is built through these micro-achievements within a recognizable, grounded (yet stylized) suburban European setting.

5. Reception & Legacy: A Silent Success in the Children’s Corner

Critical & Commercial Reception: By modern digital metrics, the game is a ghost. MobyGames shows zero critic reviews and zero player reviews for this specific title. It has been “Collected By” only one player on the site. This profound critical silence is its most telling feature. It was never reviewed by mainstream outlets; it existed outside the discourse of “games as art” or “games as tech.” Its success was purely commercial and demographic, measured in units sold to parents and children familiar with the brand.

The eBay listings (multiple active and past sales for both Windows and Mac versions) and Amazon.de historical presence prove it was a tangible, retail-distributed product. The consistent, low-price point (€4.57 – €5.99 used) and high seller ratings (“sehr guter Zustand” – very good condition) indicate it was a commonly purchased, played, and then discarded item in a child’s media rotation, much like a DVD from the film series.

Evolving Reputation & Cultural Footprint: The game’s reputation has not evolved; it has calcified. For the generation of Germans who were children between 2003 and the late 2000s, it is a nostalgic artifact—a tactile memory of a CD-ROM case, the sound of the Bananafishbones song, and the specific thrill of playing as “Fabi, der schnellste Rechtsaußen der Welt.” Its legacy is inseparable from the broader franchise. IMDb shows the film series has a stable, cult-like presence (ratings around 4-5/10 from thousands), with user reviews consistently noting its “iconic” status for its generation despite technical or acting flaws. As one user, constikdw, perfectly summarized: “People who see this movie… as adults only, they might put them aside as trash… But these movies had a great impact on the generation of people in Germany who were young when the movies were released.”

Influence on the Industry: Direct influence is negligible. It did not pioneer a mechanic or shift a genre. Its influence is sociological, not technological. It represents the final, logical stage of the “licensed children’s game” model before that market was largely cannibalized by mobile app stores and YouTube. It is a testament to the power of a creator-driven, anti-authoritarian brand (Masannek’s philosophy) that could sustain a decade-long franchise across books, film, and interactive media, all while largely flying under the radar of mainstream gaming journalism. It is a parallel development to the “Vorstadtkrokodile” (Crocodiles) series, another iconic German kids’ franchise about unsupervised outdoor adventure, showing a deep cultural appetite for narratives of self-organized, rough-and-tumble play.

6. Conclusion: A Defiantly Minor, Wildly Significant Artifact

Die wilden Fussballkerle: Alles ist gut, solange du wild bist! is not a game that stands on its mechanical merits. Devoid of its source context, it is a forgettable smorgasbord of rudimentary skill tests. Yet, within the canon of German interactive media for children, it occupies a fascinating, undervalued niche. It is a perfectly faithful digital translation of a subculture—a subculture of sand-stained knees, secret treehouse meetings, and the ecstasy of a perfectly executed trick shot against a bullying rival.

Its execution is flawed by any objective game design metric: the mini-games are simple, the presentation dated, the scope tiny. But its authenticity is unimpeachable. It does not simulate football; it simulates the fantasy of being a Wild Kerl. It turns the film’s narrative beats—house arrest, training chaos, the arrival of Vanessa—into interactive vignettes. For its intended audience in 2008, it was a potent power fantasy: a sanctioned space to be messy, rebellious, and gloriously un-cool in the eyes of adults, all while mastering a series of simple, rewarding tasks.

In the grand history of video games, this title is a footnote. But in the social history of German childhood at the turn of the millennium, it is a primary source. It is a artifact of a world where “wildness” was a marketable, philosophical stance, where getting dirty was a revolutionary act, and where a simple mini-game about keeping a ball in the air was, for a moment, the most important thing in the world. That it is preserved, even in obscurity on a used-CD marketplace, is a victory in itself. Alles ist gut, solange du wild bist. And for a brief, shining moment in a CD-ROM drive, this game was, indeed, wild.